To Ukraine with Love: Drawings of a Japanese Prisoner of War

Born in Tokyo in 1923. In 1944 he was conscripted into the Japanese army. After Japan had surrendered, he was captured by the Soviets and sent to Ukraine. Upon his returning home, he created a series of watercolors on his life in captivity. His drawings were listed as UNESCO World Heritage. Nobuo died in 2021.

On the World War II ending, around 6 thousand captured Japanese soldiers and officers were distributed between the work camps throughout the whole USSR. One of them was a 23-years-old paratrooper Nobuo Kiuchi who was sent to Ukraine together with the other captives.

He spent 2 and a half years in Donbas — in the camps of Slovyansk and Kramatrorsk. After he returned home in 1948, he started drawing the episodes of his life in captivity in order to commemorate his fallen comrades. In general, Nobuo created over 80 drawings, each described in several sentences. In his drawings he often humorously depicts simple human feelings, ascribed to the winners as well as to the conquered ones.

Nobuo died in 2021 in Tokyo at the age of 97. Kiuchi’s art is popularized by his son Masato who created a special website in his memory. “I guess the ongoing war in Ukraine would have pretty much upset my father. Because he always said that there are no winners in war. Regardless of the final outcome, each side bears huge losses. His only desire was for peace to be established in the world from now on. This is my wish as well,” says Masato.

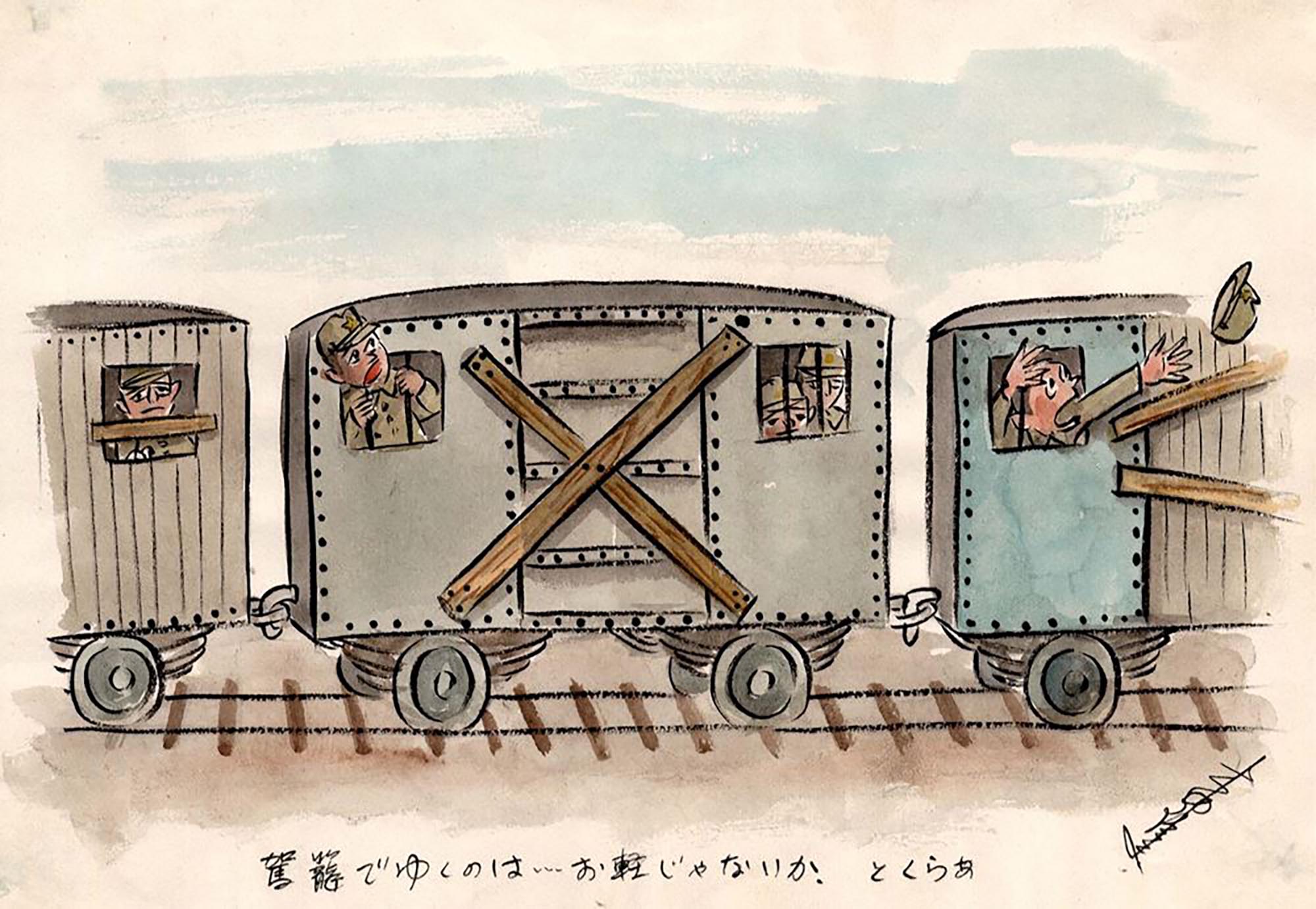

40 people were loaded into a freight car, accompanied by the shouts 'Come on! Come on!', the door was tightly closed from the outside. The wagons were guarded by Soviet soldiers with machine guns. A train with about 1,500 Japanese prisoners set off on a long journey to the west.

Our train was heading along the Trans-Siberian highway and, upon crossing the Urals, reached Europe. The journey lasted 30 long days. Finally, we arrived in the small Ukrainian town of Slovyansk. A cute barefoot girl was walking through a field of sunflowers, grazing the goat kids in front of her.

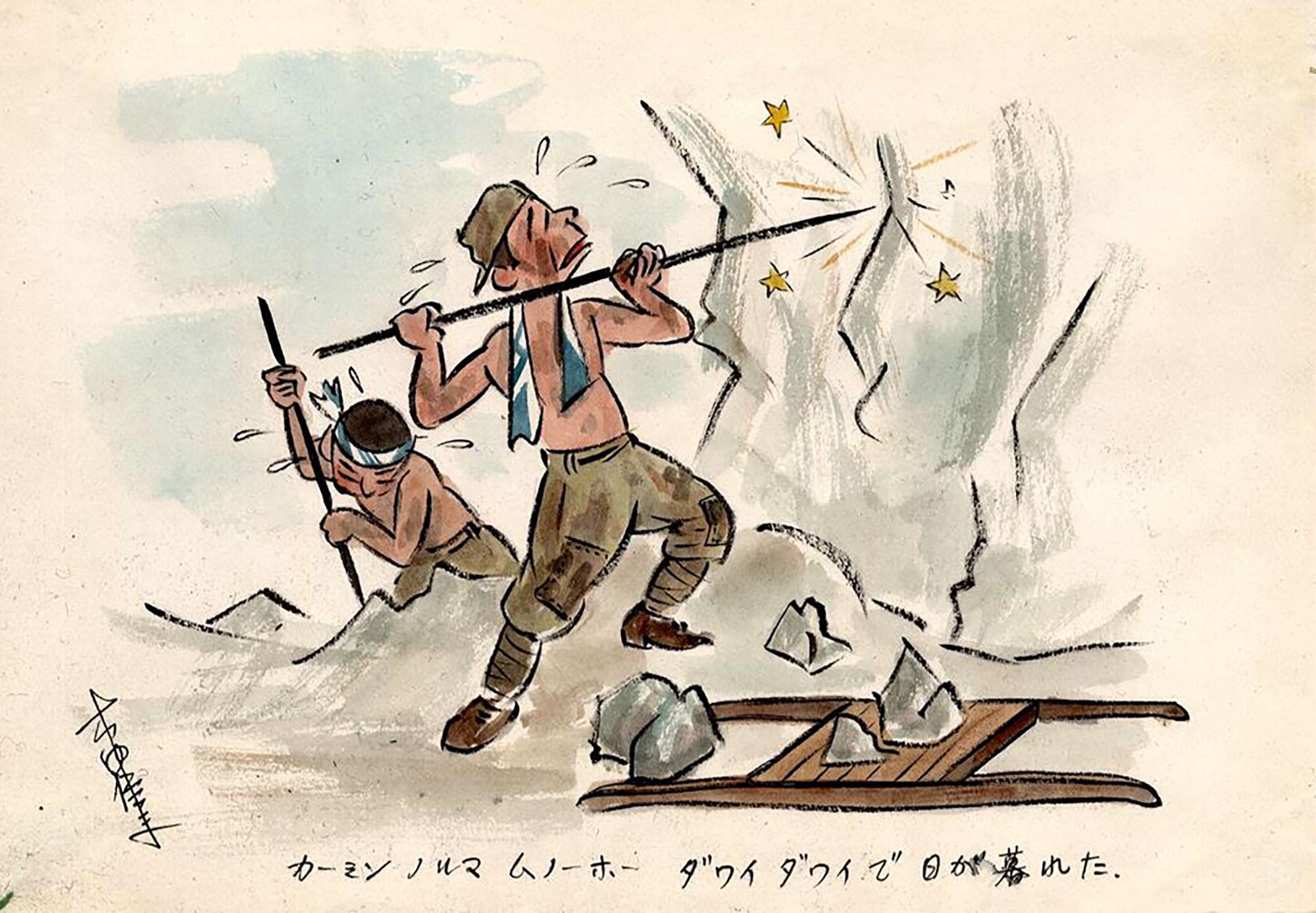

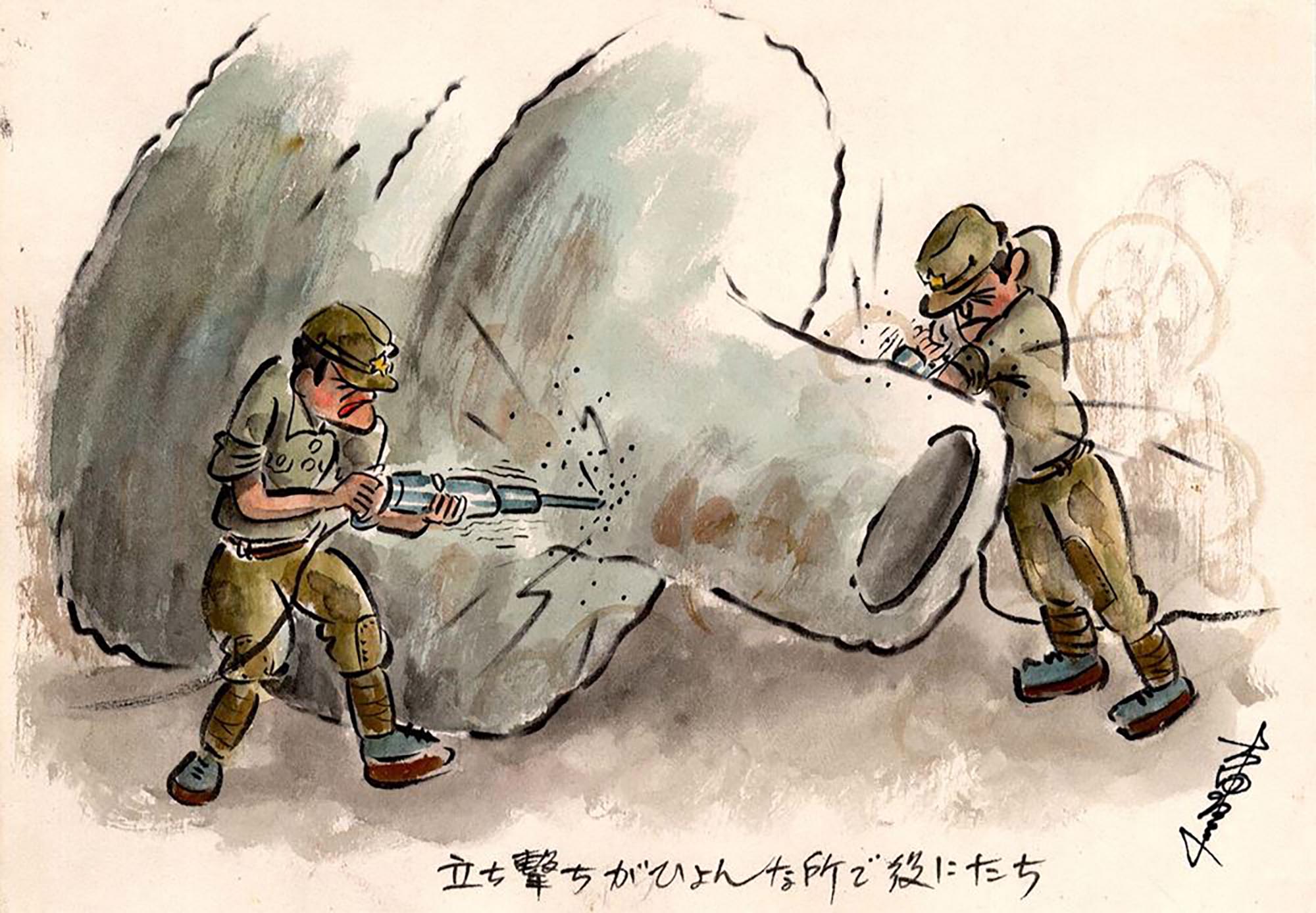

He who does not work — does not eat. We immediately started working on chipping stones. With a crowbar in hand, we stood in front of a stone block and carried out the daily norm of one cubic meter per person. Working in a team of four is terrible anyway, because the workload is quadrupled, including the work of a loader and a carrier.

What is the point in telling the sergeant I need a bathroom break if he still doesn't understand me. Afraid I might get off, he was always looking what I do, standing right beside me. And I couldn't do it because of it.

I tried somehow to work with a Slavic kosa (scythe). It was easy for a young girl, but I was just sweating. "This is because you can't turn your back," she said.

"Here you go, Japanese, hold the potato." In any country, girls are very kind. They say that Ukraine is a fertile land and that is why there are a lot of potatoes there.

In winter, we were sometimes loaded into cars and taken somewhere for a long time. My friend and I had a task to shatter the ice on the river. You could slip and fall at a glimpse. What a wide river, I thought. It was Dnipro.

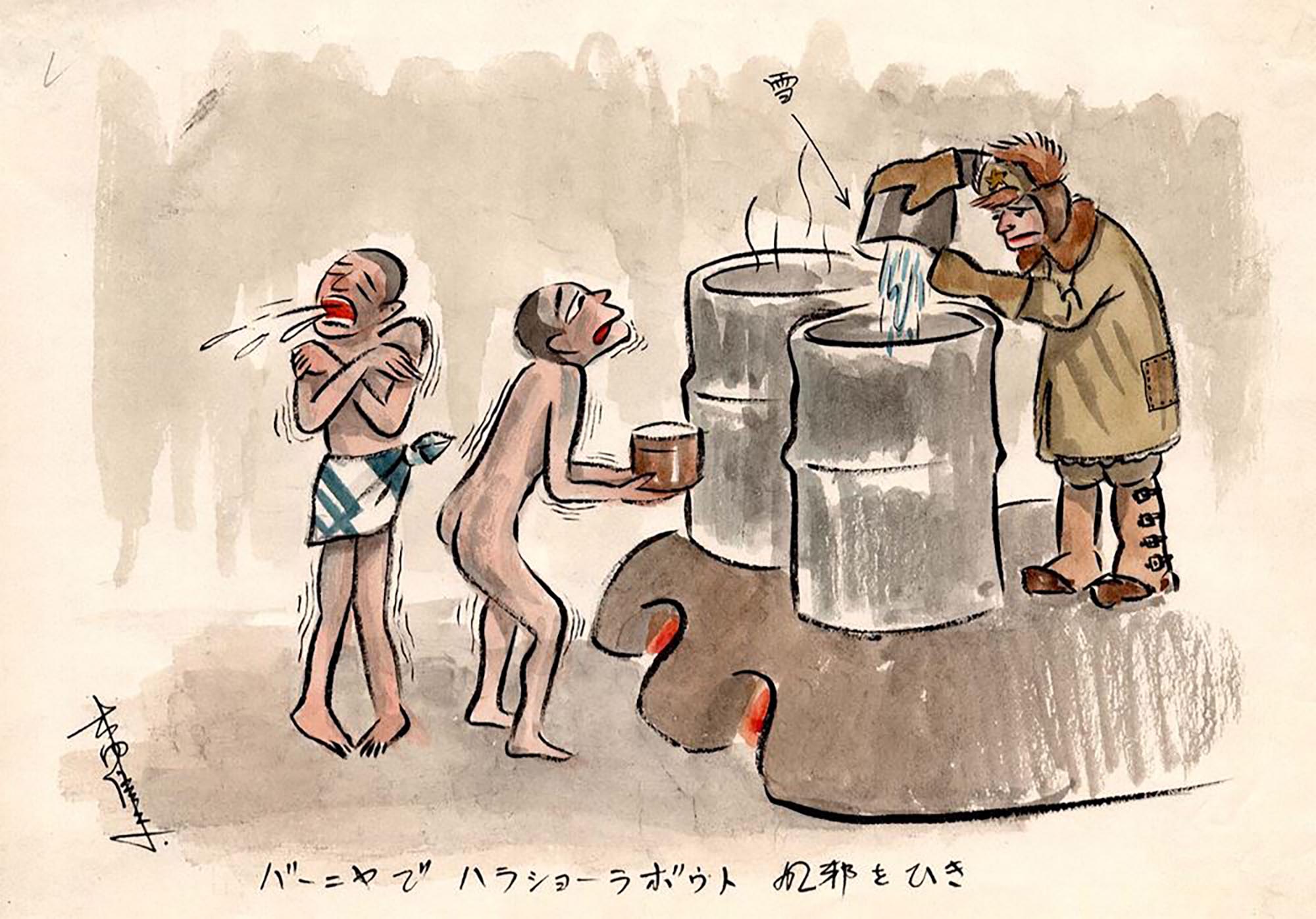

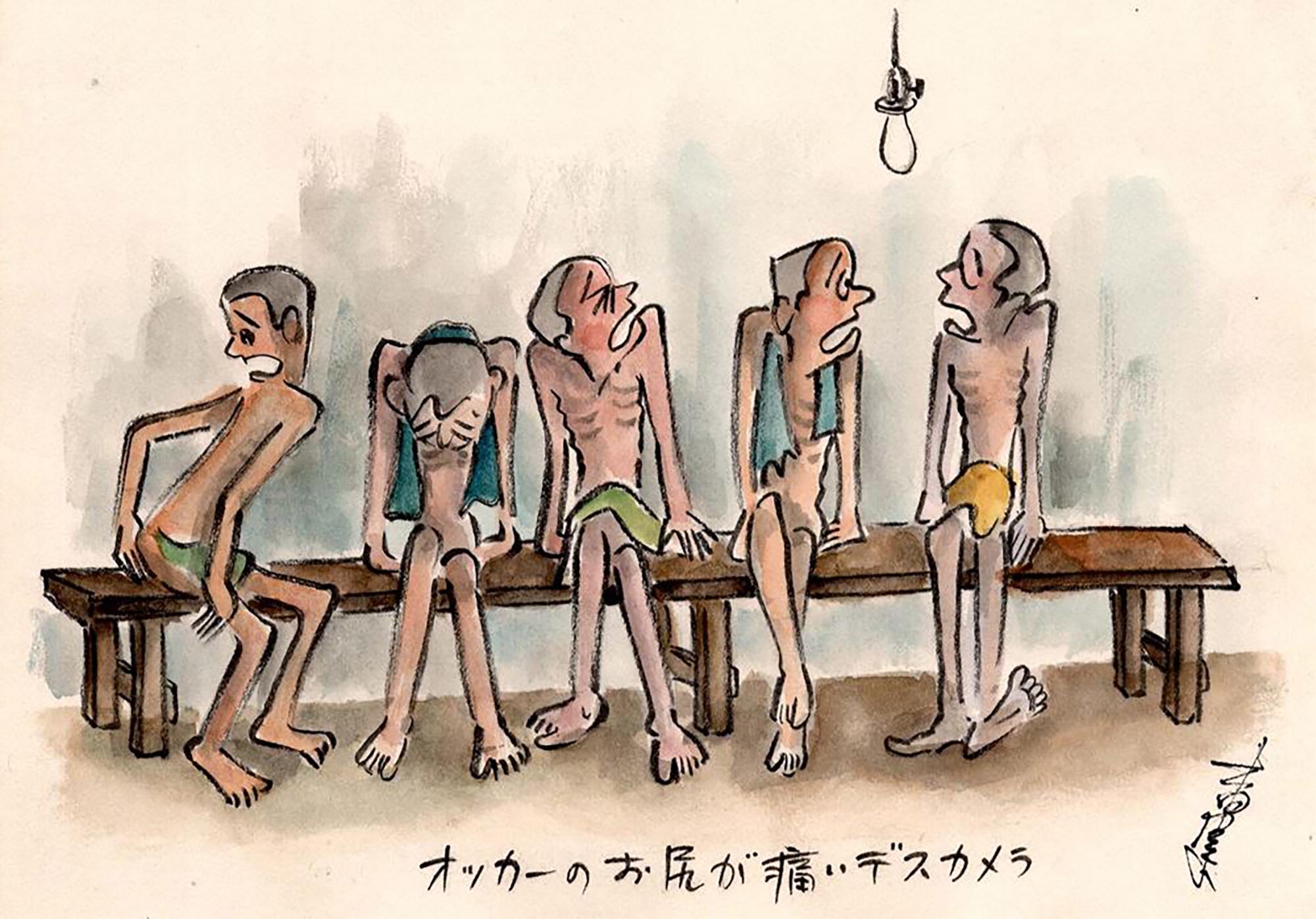

Soviet doctors ordered to take us to the bathhouse. To the bathhouse, at −25°С?! This, I tell you, is not a joke at all. If we weren't so young and healthy, we could easily die of hypothermia. We melted the snow in iron barrels, and everyone washed in the cold with one cup of water. And then I felt the cold kiss of death once again.

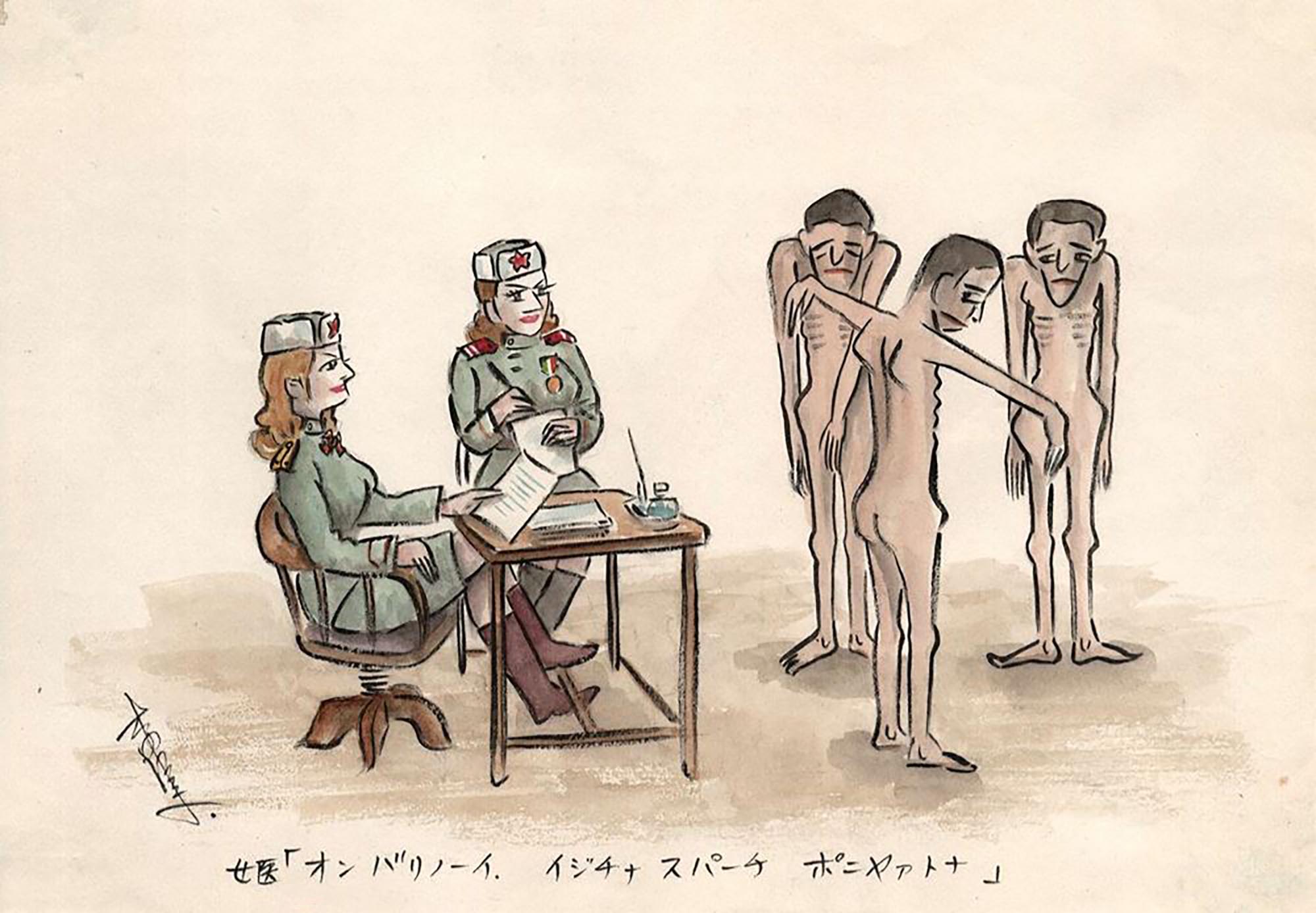

Doctors were mostly women. A beautiful lieutenant doctor with ample breasts, aware of her good sides, walks by with her shoulders back... There is no disdain for other nationalities in this multi-ethnic country. And Japanese prisoners of war were examined individually, like any other person.

In a country where men and women are equal, a woman soldier came to us as a surprise. The Japanese, who still lived in the good old patriarchy, were shocked by this phenomenon. Resistant to the cold weather, resolute, devoid of any softness, women in the Soviet army were wonderful.

"You have to sweep thoroughly!". We had such a terrible auntie-officer. But it was fun. After wiping the dirt in the hall, it was necessary to carefully clean everything afterwards. And with unexpected checks it wasn't easy to slack off.

Once I had to appear in front of the doctor in a not quite decent way. She was especially worried about emaciated soldiers, persistently putting them to bed: "Time to sleep!". She had a nice voice.

Tears cannot be stopped. I cried non-stop all day. It's just terrifying when someone dies in front of you. I promised to tell his mother everything, if only I returned home myself.

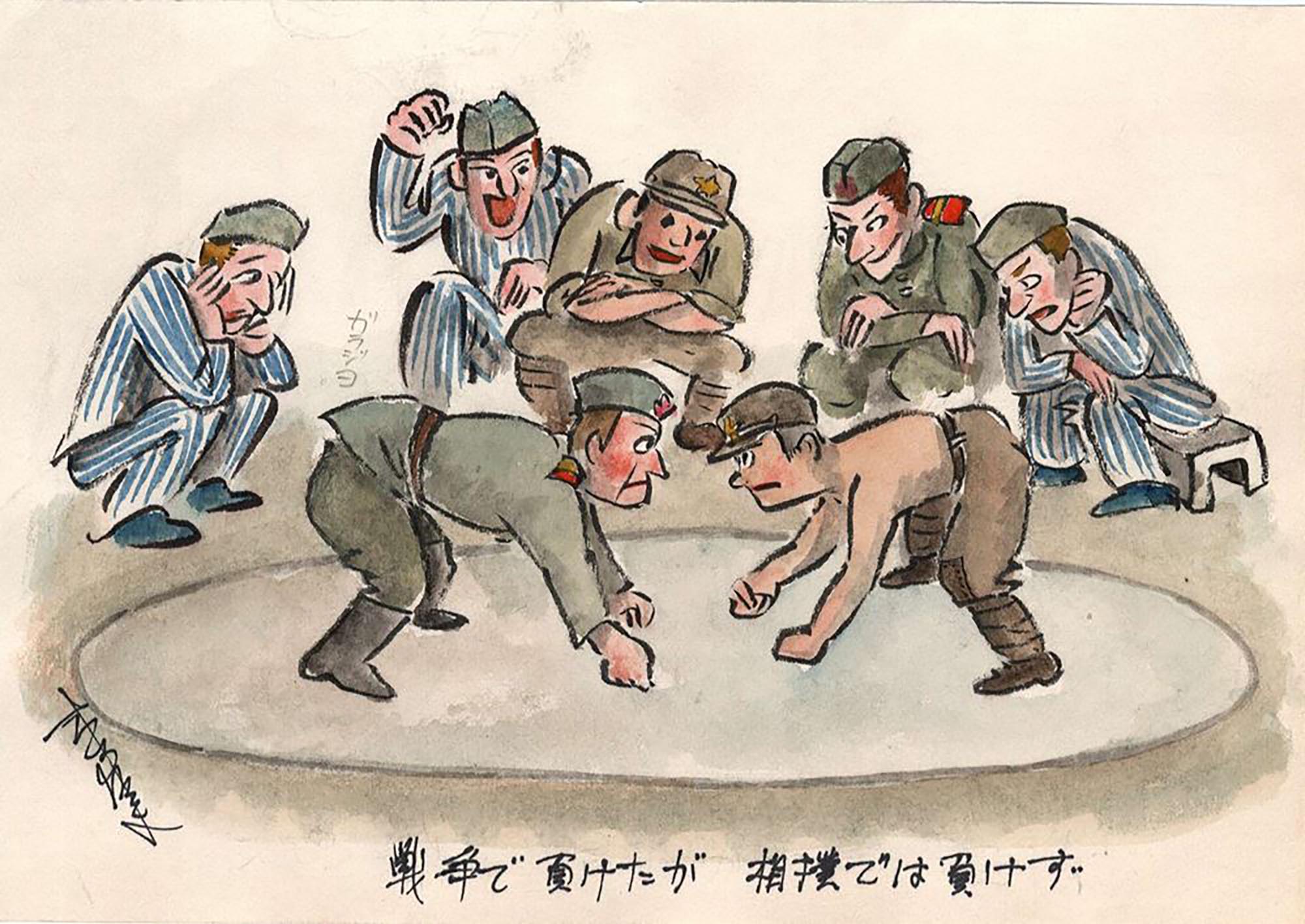

"Mikado", "geisha", "Fujiyama", "judo", "harakiri". Slavs know these words. But when it came to sumo, it turned out that no one had a good grasp of the rules. Even after losing, they said "thank you".

Simple-minded naive Soviet children did not pay attention to racial differences at all. The fact that I had the chance to play with them can be regarded as a huge sign of luck. And I learned a lot of new words with them. I love children very much!

According to the plan, the city reconstruction was meant to last five years, so young girls also took part in it, fully devoting themselves to work. Both men and women did well.

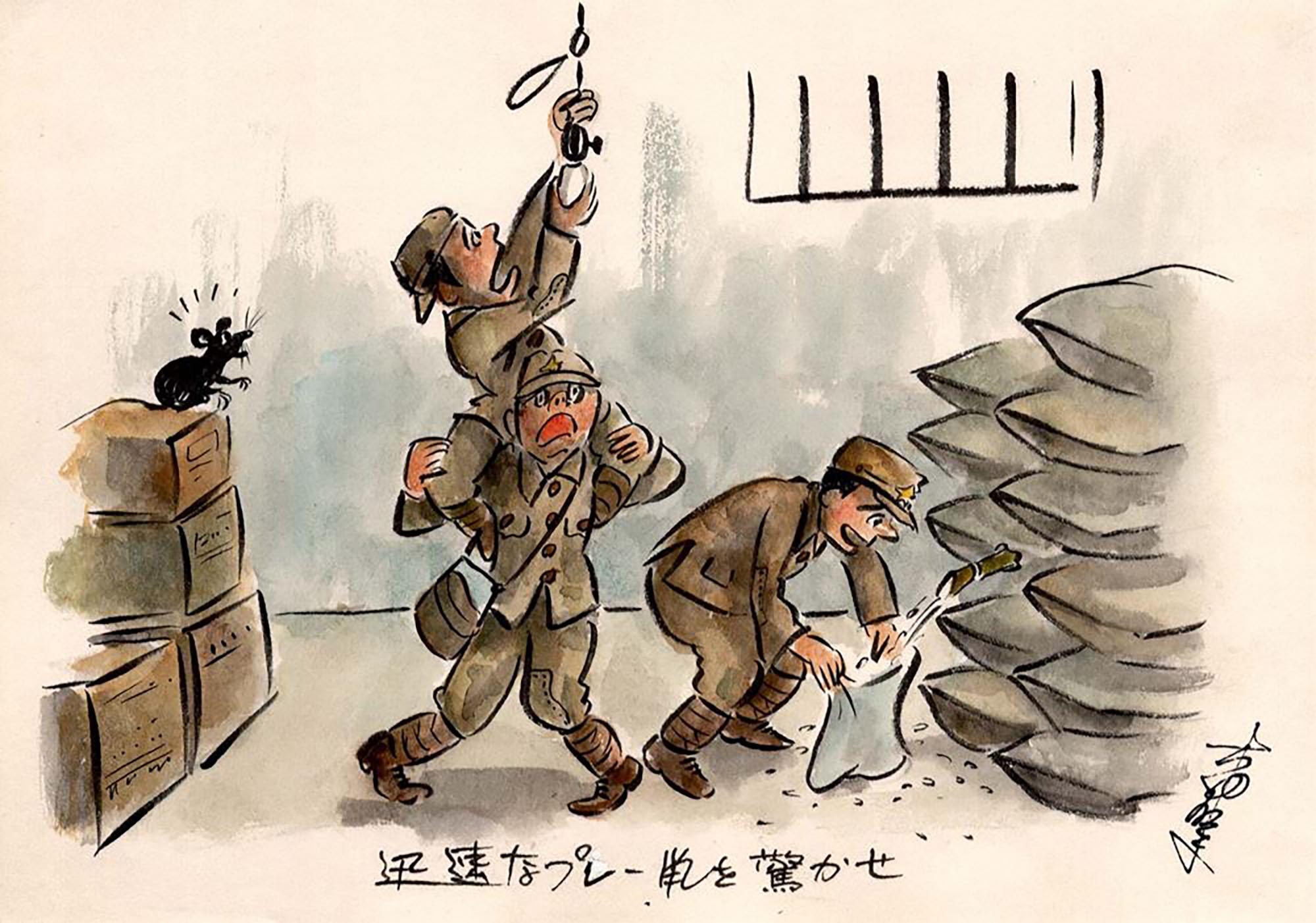

After work, we stole electric bulbs to make the camp at least a little brighter. We wanted to eat, and we, having pierced rice bags with a bamboo stick, poured the grain, although we did not manage to take much.

This is a train wheel. We worked with a pneumatic hammer, leveling the surface of the wheel. A shrapnel cut my eye, I stopped seeing, and a German doctor operated on me.

I spent the next two months in a hospital in Druzhkivka. I lost my sight for two weeks. There I made friends with my comrades in arms and a young German soldier. When I was able to see again, I decided to take charge of the severely ill - as a sign of gratitude for the help given to me. I was happy to think that I had been useful.

Once or twice a month we went to the bathhouse. It was painful to sit on the benches, because of how thin bones directly touched the hard surface of the bench.

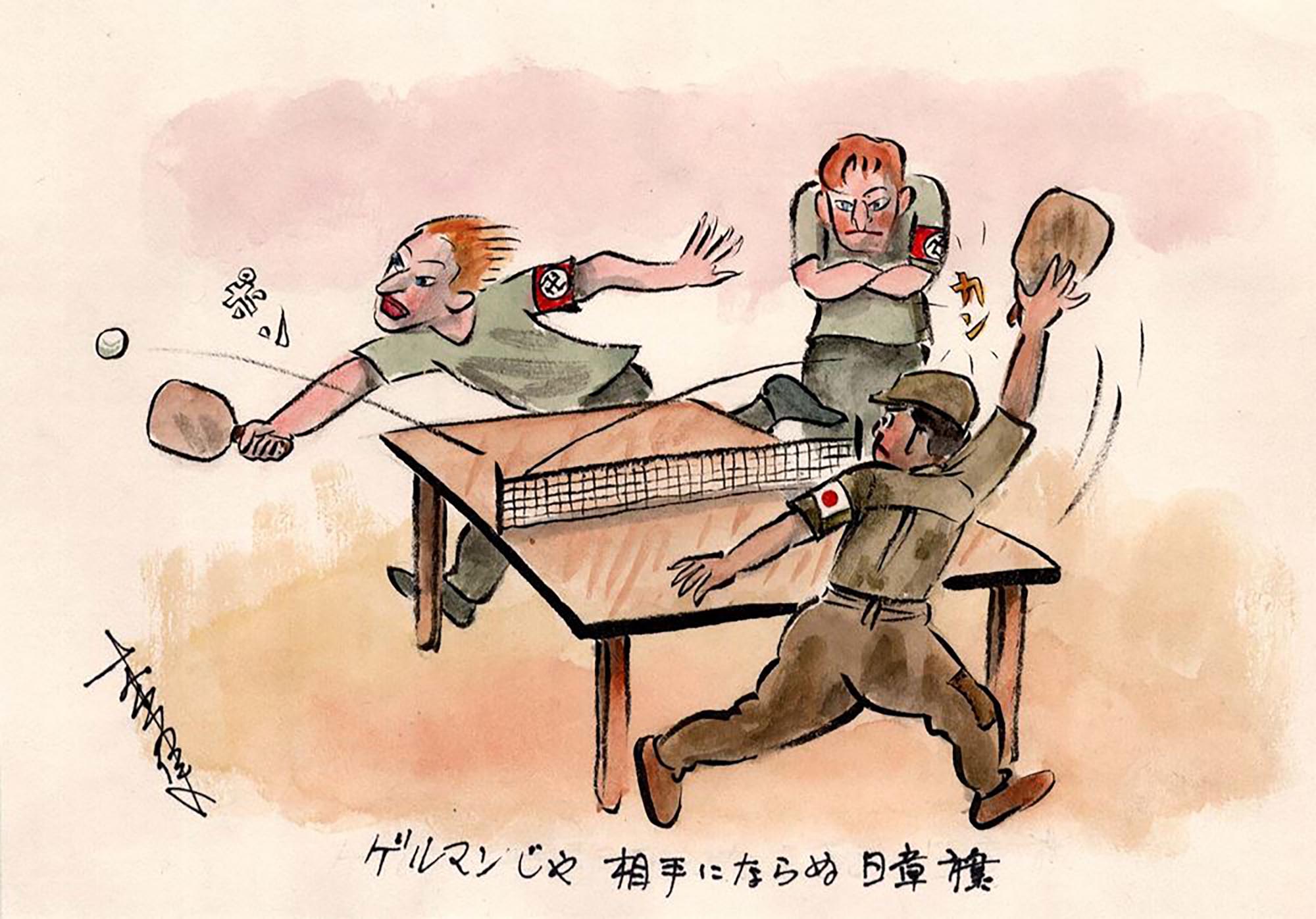

Japanese prisoners of war arranged a table tennis tournament with the Germans. Perhaps it was because of the strange manner of holding the racket that the Japanese easily won.

Both men and women took part in the reconstruction of the city after the end of the World War ІІ. Brave women coped with even the most dangerous work. At that time, it was difficult to imagine such a scene in Japan. There were even cases of Soviet women showing love for Japanese soldiers. Those were wonderful moments.

But after all, envy of someone else's plate is the same everywhere. Due to the fact that Japanese dishes look bigger, Germans cast angry glances at them. They have bread and soup, we have rice porridge, miso soup and other things.

All night until morning, I and a friend who graduated from a music school, write notes from memory. In the morning, we give them to the German orchestra, and then it plays Japanese pieces for us. We do not know their language and cannot speak the language of words, but we can speak the language of music. Joy from the anticipation of returning home grows.

Every meeting is inevitably followed by parting. There was one girl for whom it was particularly painful. And you, Natalka, who were whispering words of farewell so bitterly, what are you doing now, what happened to you, poor thing?

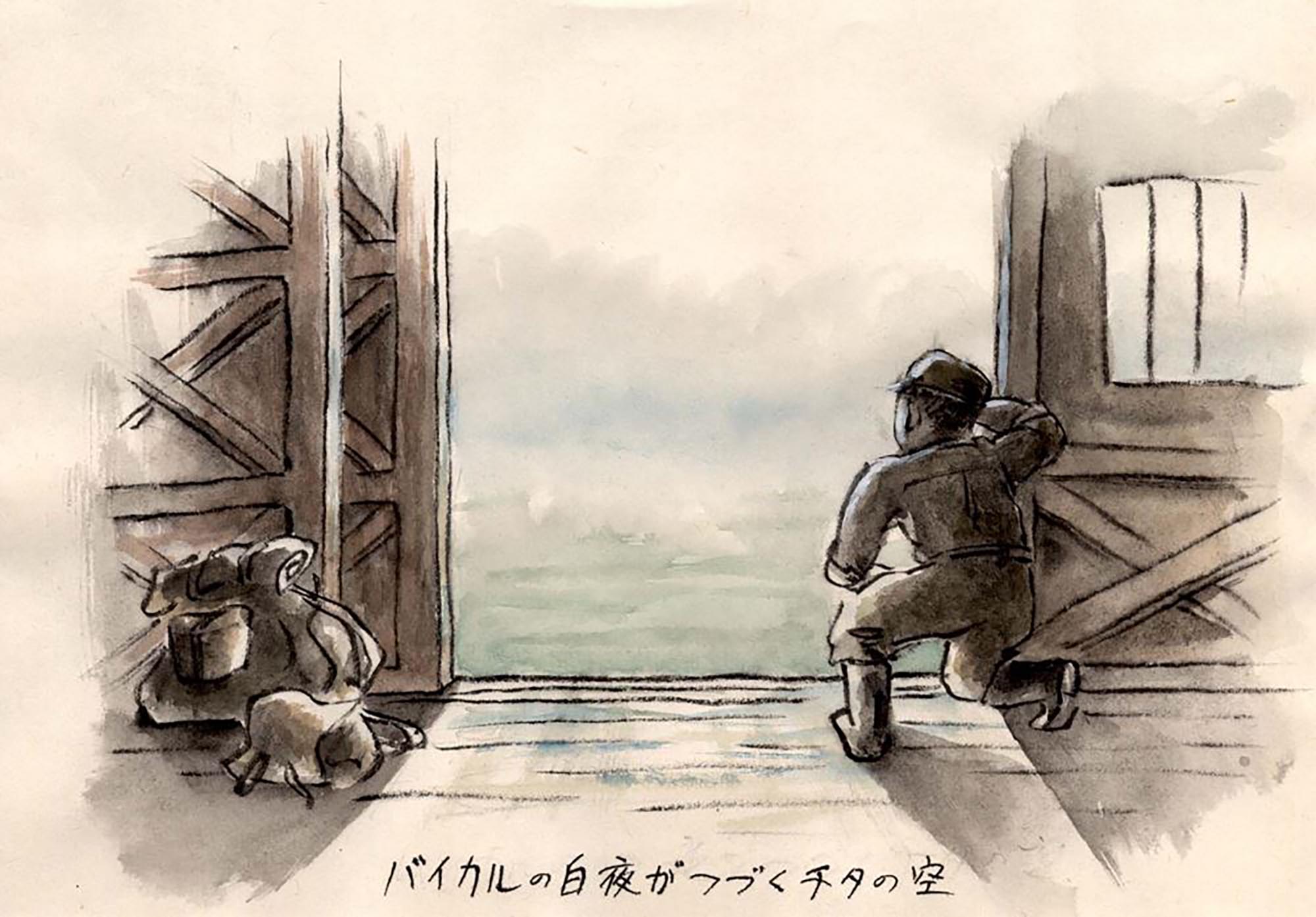

Unlike the train we used to enter the USSR, the doors on this train were wide open. In this part of the world, in Siberia, the sun does not have time to set completely, and even in the dead of night it is clear here. These are the so-called white nights. We are going east along the long Siberian railway...

It is difficult to force yourself to use the toilet box on the train. Therefore, at each stop, we climb out of the wagon, sit like birds on the rails and leave "gifts" on the roads.

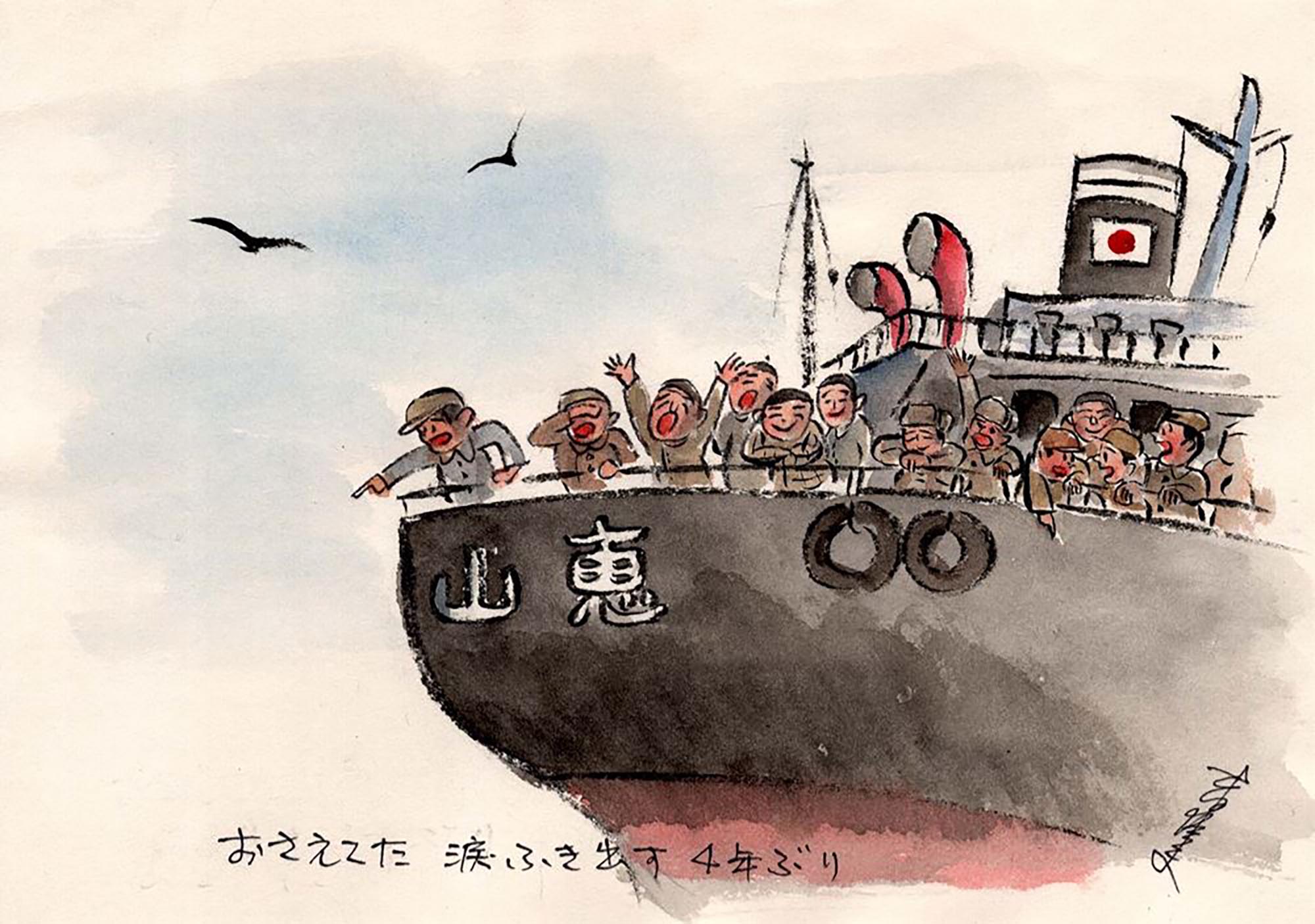

Even the defeated country has rivers and mountains. Here they are - Japanese islands covered in greenery. The view of the Maizuru port brings tears of joy. Some soldiers have not been home for 10 years.

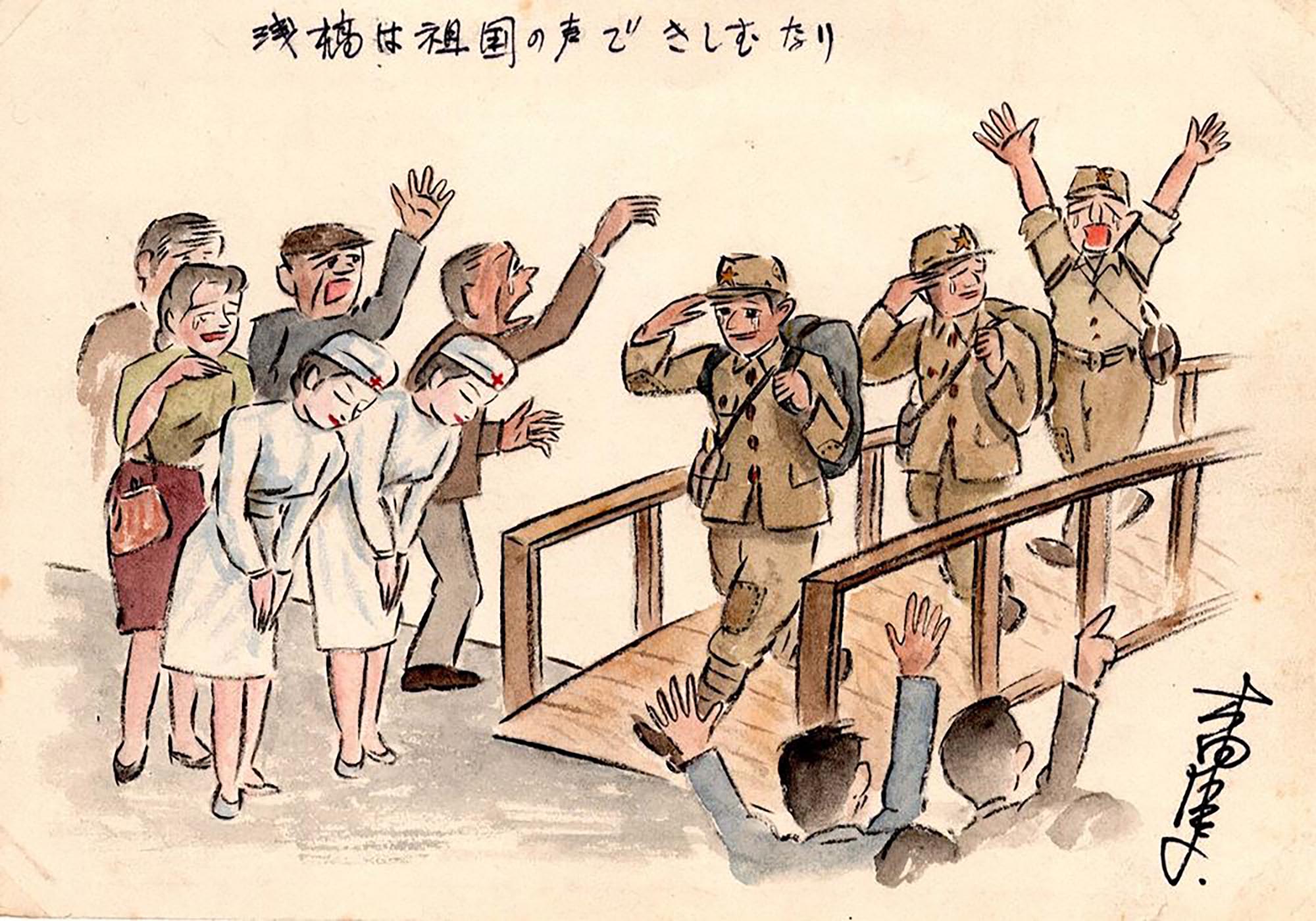

I set foot on my native land and heard the creaking of the pier boards, and heard the sound of my footsteps. People on the shore all shouted "hooray", thanked us, and shook our hands. One could discern the nurses of the Japanese Red Cross in their white clothes shining in the crowd.

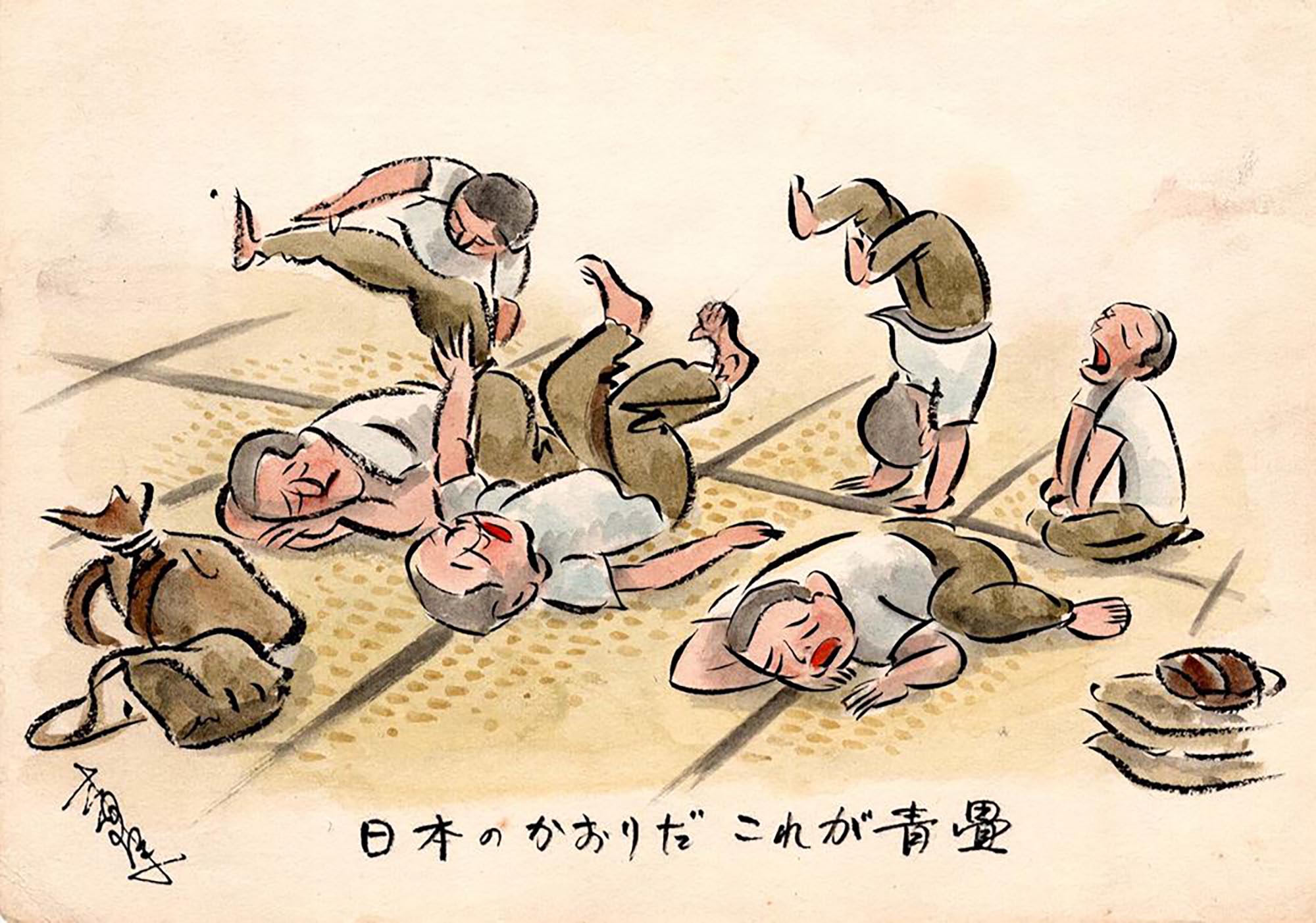

"Tatami! Tatami!”. We rolled over on them, stood on our heads, pressed our cheeks to them - our so dear tatami! Just like a mother to us. How glad I am! It was then that I felt for sure that I had finally returned home.

Artwork provided by Masato Kiuchi. Owned by Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum.

New and best