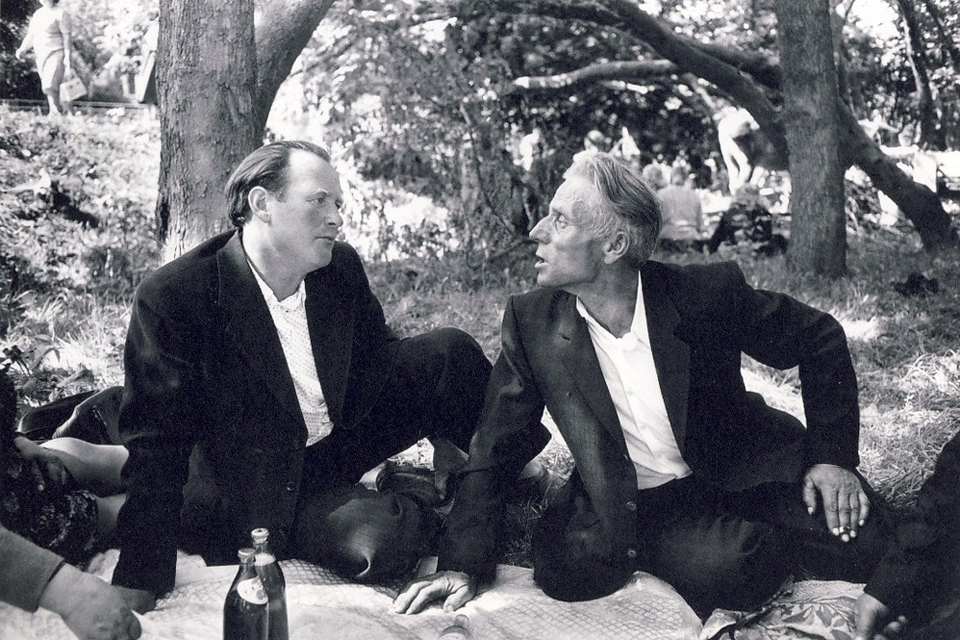

Antanas Sutkus: “What to Do, — Sartre said. — You Should at Least Send Me the Photos.”

Documentary photographer, founder and chair of the Union of Lithuanian Art Photographers. His main theme is the people of his country, but his most known photograph is a portrait of Jean-Paul Sartre. In recent years he works with his archives most of his time, choosing photographs that were impossible to print in the Soviet Union.

In your opinion, what has been behind the success of the Lithuanian school of photography?

The phenomenon of the Lithuanian school is the talent of several authors. In 1965, I accompanied Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir on their trip around Lithuania. On the last day of his trip, Sartre asked me: “How many talented photographers do you have in your country?” With the straightforwardness of a young person, I replied: “Five, six if you add me.” But I was wrong: at that time, there were ten really talented photographers in Lithuania. And now I know that ten talents in one generation is a lot.

What else did the Lithuanian photographers need, except talent?

To be successful, a talented photographer needs to be a bit of an idealist: love his people, his theme, and his country. In the formative years of the Lithuanian school we were all very idealistic. We wanted to convey the uniqueness of Lithuania. The Union of Art Photographers was a serious help, when it started earning on exhibitions, photo books, and publications. Photo books were popular inside the country, and photography was popular in the world. The money we earned was spent on paper, printing, and film. Photographers who were members of the Union did not spend money on printing photos for their exhibitions or film.

And now I know that ten talents in one generation is a lot.

An editor for the American Popular Photography magazine once approached me to find out how the Union works. He said that nowhere in the world there were such working conditions for a photographer. The number of copies for our photo books impressed him. At that time, we printed 200,000 copies of one photo book, so he had to ask me several times, whether I got my zeros right. 200,000 for America is a serious figure, it is what bestsellers get. It was unthinkable for him that these figures came up in a country with a population of 3 mln.

All photographers of the Lithuanian school spent many years working on projects — this was the rule you set. Why did you insist on long-term projects?

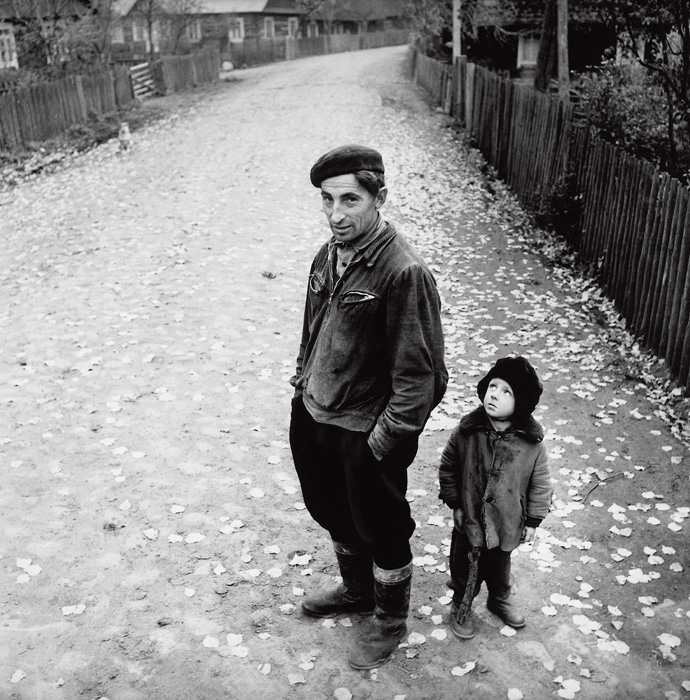

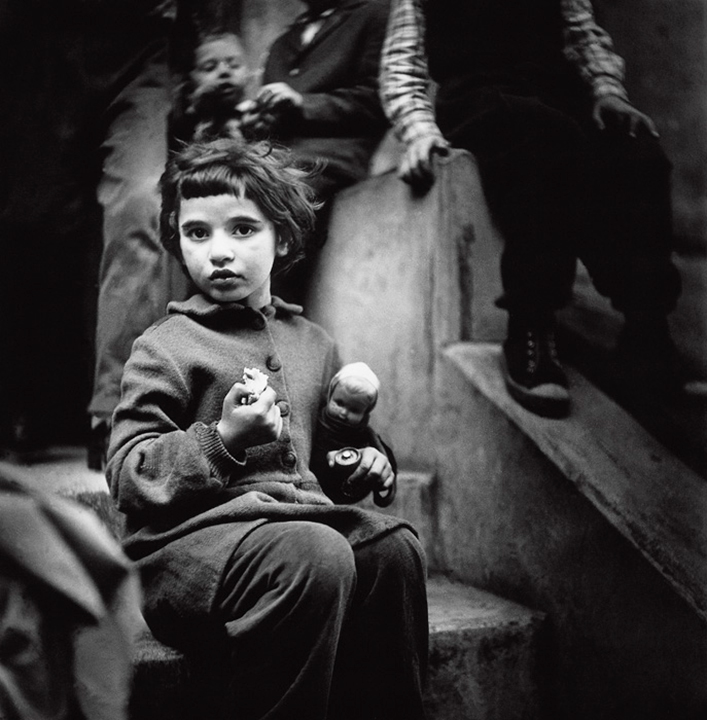

Here is what I think: if a photographer found a long-term theme, it is his blessing and his curse at the same time. The theme will follow him, whether he wants it or not. He will feel every turn, and will hardly be able to leave it halfway. Currently, I am the only one from the Union who stopped working on my theme. And when I say stopped, I mean that I stopped shooting, but I continue working with archives, and I don’t see the end of it yet. There is still a pile of negatives in the archive, and in the Soviet era I couldn’t print even the most innocent things. For instance, I offered to call my current exhibition in Moscow “Ragamuffins”. Can you imagine, what would have happened if even a couple photographs of ragamuffins saw the light of the day in the USSR? I would have been accused of slander against the Soviet reality. No ragamuffins could be in the USSR, where everyone should have been dressed as it should be, and so on.

Is it difficult to dig into the past while looking through your archives?

A negative can cut you like a blade and hurt you deeply. Sometimes you stumble upon the dark sides of your past that you have successfully forgotten. And then you print it, and it becomes as real as if it were yesterday. But difficult memories are not the most complicated thing about working with archives. The most complicated thing is to remain true to yourself, not lie to yourself when selecting pictures.

Has anything changed in your attitude to your projects in the years that you’ve worked on them? For instance, you spent several decades on Faces of Lithuania.

I despise the term ‘project’ itself, you can have a construction project, but not an art project. In construction, you plan whether to build 26 or 62 floors, but you can’t plan anything in art. Talent decides here: you either have it or you don’t. When taking portraits of Lithuanians, I was not thinking about any project. Faces of Lithuania is an idea, a theme that has led me. Nothing changed in my attitude to it: I met people, I got to know them, and I photographed them. They were often people from my close circle: friends, friends of friends, and likeminded people. We were all united by being somewhat freethinkers, who didn’t like the Soviet regime.

I despise the term ‘project’ itself, you can have a construction project, but not an art project.

In his time, my father chose not to compromise with the Soviet regime. He refused to sign some fabricated documents, and shot himself in the first year of Soviet rule. If he didn’t do it, our whole family would have been deported. I know that in photography I follow not only my theme, but also my father.

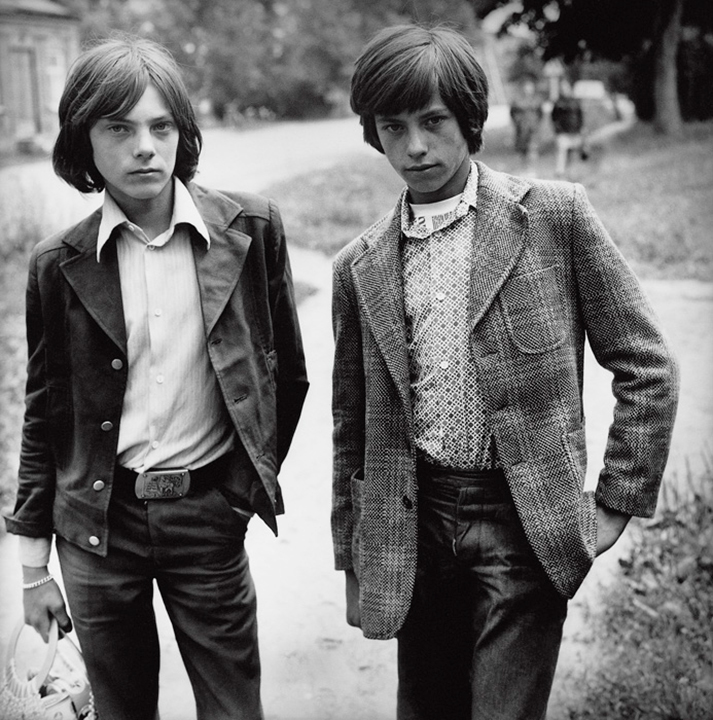

You took pictures of children, too. Were they also children of friends?

The children were different, mostly just from the streets. We tend to think that children are our extensions, a reflection of the adult world, but this is not true. Children have a life of their own, a world of their own with its own laws, rules, its own happiness and sadness. It is a parallel reality, if you will. To enter it, you need to go back to being a child, feel that you are a kid. Adults and children are different stories.

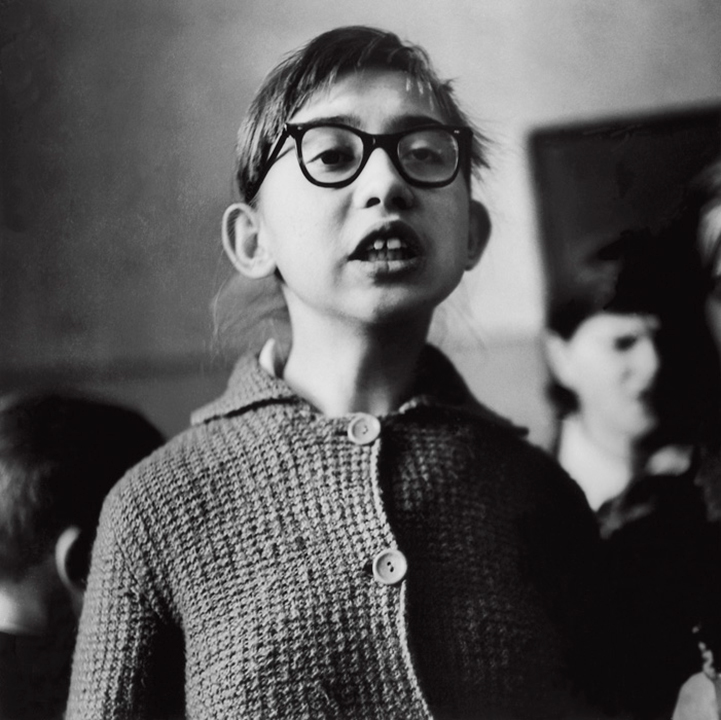

Could you tell us about your famous photo, Pioneer? How did you take it?

I was on a business trip in a small town of Zarasai. I woke up early and saw children with flowers. “Where are you going with the flowers,” — I asked. “Don’t you know, it’s September 1 today,” — they replied. “No, I forgot.” “Come with us, to remember.” And I followed them. The ceremonial formation in front of the school just started. While I was circling in the street around the excited schoolchildren and their parents, I took “Pioneer”, “Father’s Hand”, and several more stories. All of them are classics today. It happens: you take three or four great pictures in half an hour, and then nothing worthy for half a year.

I was recently asked in St. Petersburg: why does you pioneer look like he just escaped a concentration camp? I replied: “He is not from a concentration camp, but from a socialist camp. It wasn’t easy there either.” I could not have replied like this in 1970, when Russian pensioners attacked the Ministry of Culture with letters. The pensioners wrote after the photo was published in Soviet Photo: “what kind of a pioneer from a concentration camp is that?”, “what kind of a photographic Solzhenitsyn is that?”. I am grateful to Bugayeva, editor-in-chief of the magazine, who hushed up this story.

It happens: you take three or four great pictures in half an hour, and then nothing worthy for half a year.

I think I still have that image of a ‘photographic Solzhenitsyn’. I just opened the catalogue for the Soviet Photography exhibition in Oscar Niemeyer’s Museum the other day, and it read: “1970: Solzhenitsyn received a Nobel prize…, and Sutkus received a Golden Michelangelo for his photo of a pioneer.”

Did it ever happen that you had to stage a portrait, influence a situation somehow?

Almost never. I was commissioned to take photographs for the honor board in a Belarusian village. I had to ask the local heroes to pose. But there was so much character in them that nothing could spoil the pictures. Even the picture of the head of the kolkhoz turned out well. In general, though, I tried for people not to notice me. If Sartre noticed I was taking pictures of him, he would have refused my services immediately. And he had no idea I was a photographer before I told him myself. “What to do, — Sartre said. — You should at least send me the photos.”

Do you know what happened to those photographs? Has Sartre ever used them?

After Sartre’s death his archive was sent to one agency, and for a long time they credited my picture to Henri Cartier-Bresson. This photograph is almost classic in France, it made all the textbooks. I was once accused of plagiarism and told that even the schoolchildren know this is Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph. I had to prove that the picture was mine. This way or the other, today this picture is my and Sartre’s calling card. This is my most famous photograph.

“What to do, — Sartre said. — You should at least send me the photos.”

More and more often the galleries show the works of black-and-white photography classics that were shot in color. It turns out that they had a great feeling of color. Is this ever happening to you?

I have not sinned in shooting my main theme in color. I did use color film sometimes, though. When I shot Lithuania in color, I did it for advertising purposes, to show it in a positive light and to draw the attention of spectators and travelers to it. A photo book with my photographs was printed on good quality paper, and extra copies were republished several times. My joke about this is that black-and-white photography is a wife, and color photography is a lover.

Aren’t you interested in the new faces of Lithuania today? Don’t you want to take several more portraits for your gallery?

I feel my obligation to the archive, I have to find all the photographs there that I have not found before. I dug so deep into it that I started losing the photographs that I have already just found, getting confused, and looking for the things that I’ve already found again. This is a tremendous amount of work, and this is what’s most important to me now. And the new faces are captured by new photographers. It is a pity that young photographers follow the global trends and are not too keen on the Lithuanian traditions that were so important to our generation.

All photographs courtesy of the press service of The Lumiere Brothers Center for Photography. The exhibition Nostalgia for Bare Feet is open between April 7 and May 29, 2016, in the Great Hall of The Lumiere Brothers Center for Photography in Moscow at 3 Bolotnaya Embankment, bd. 1.

New and best