“Don’t Ask Me How David’s Mind Worked”: George Underwood and Steve Schapiro about David Bowie

British artist and illustrator. As a young man sang in bands together with David Bowie, and later created album covers for him, T. Rex, Procol Harum, and Mott the Hoople.

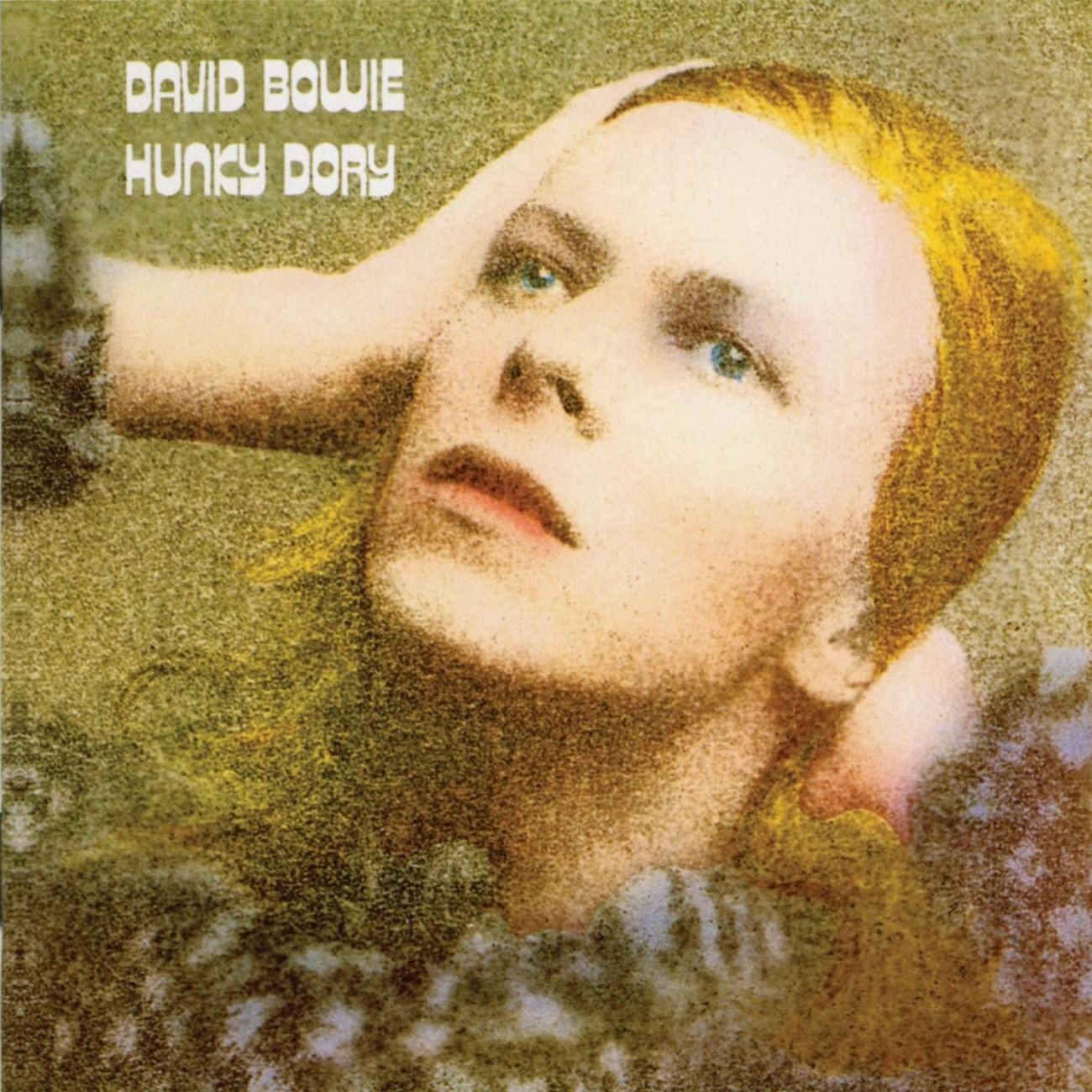

I love the work you did with Hunky Dory cover. Could you tell me about it? Did Bowie come here with a picture of Marlene Dietrich that he wanted to imitate?

Not quite. Brian Ward who took the photograph set it up to look in Marlene Dietrich’s style but I don’t know the photograph that you might be talking about. It could have been a photograph of my mother, actually, which was a hand-tinted photograph, that David had seen and he said to me that he wanted his colored a bit like that one. So, I got the rough idea what he wanted.

David always knew exactly what he wanted usually. I wanted to do a painting of that cover, but there wasn’t enough time. At the studio where I worked at the time there was me and another chap, Terry. He airbrushed the cover, and I wasn’t sure it was going to work, but David liked it, and everyone else liked it.

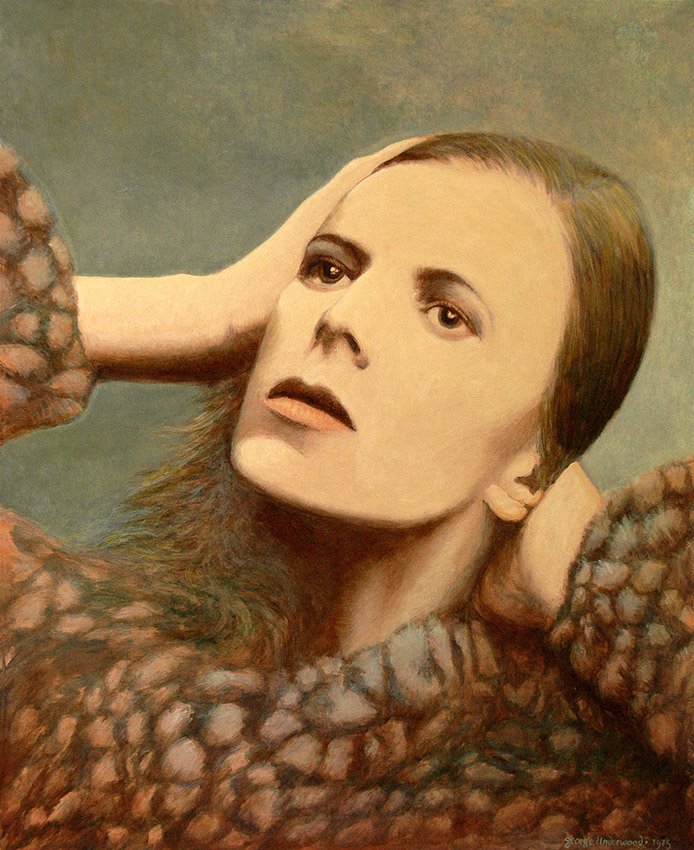

But I did a painting of how I would like to [do it], if I’d had time. Unfortunately, David… Anyway, it’s a long story.

Hunky Dory cover

George Underwood’s painting

Why Marlene Dietrich?

I think, he was going through a Marlene Dietrich phase (chuckles).

She had a very specific screen image, this femme fatale thing. Probably she was as provocative as Bowie later was.

I think, it was Marlene-Dietrich-esque, in the same feel as that period. Don’t ask me how David’s mind works. Sometimes he’d come out with the most sideways way to look at things. He woke up that morning and decided that was how he wanted the cover to look. It was very changeable, he might have decided the next cover was going to be very different, which it was.

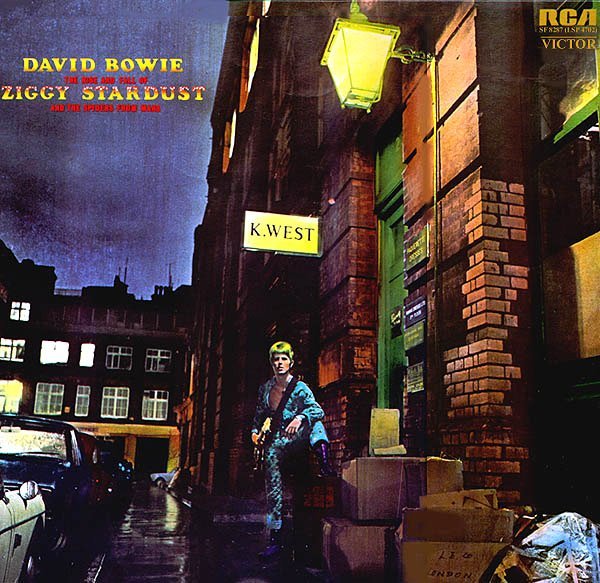

Ziggy Stardust. And they were made almost at the same time?

Brian Ward’s studio was in Heddon Street, it was where it was filmed. So, when they went out to take shot for the cover, David all dressed up in his gear and everything, it started pouring rain. So, he ducked inside this telephone booth. Perfect.

Your style is also very different in these two works. Was it easy for you to switch like this?

Actually, that wasn’t difficult at all. Brian Ward has done all the work, the colorization wasn’t something that was difficult. Painting, that’s what I do, so coloring photographs is okay.

Why did you stop working with David?

No, I think, David moved on. I didn’t actually stop working with him — I just didn’t do work for him. When Diamond Dogs came along, he asked “Do you got any ideas for that?”, and I said, “Yeah, I could do a paint of that if you want.” And he said: “If you don’t mind, I’ll use Guy Peellaert for that. And I said: “Yeah, fine, use whoever you want.”

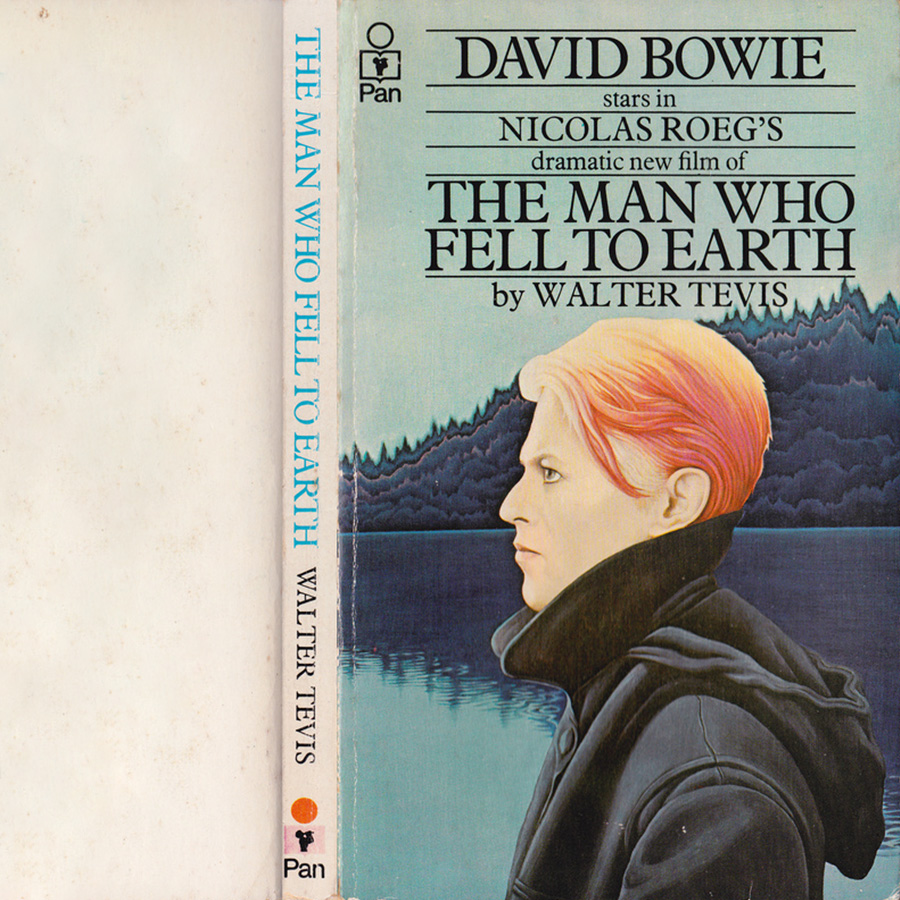

Strangely, I did the book cover for The Man Who Fell to Earth [it was reprinted for the release of the film where David played]. When they were asking me to do the book cover, the film hadn’t been released, they asked me if I could get permission from David to use his photograph. And I said: “Yeah, absolutely fine.” So, I try to get hold of him for it, he was in America somewhere, I managed to get a phone number from his management, I rang up, and it rang for a while, and then an answering machine clicked on. I said: “Hi David, it’s George here, I just want to talk to you about a book cover I am doing, and it has your face on it, we need your permission, can you give us a ring back? I’m happy, hope you’re happy, too.” When I heard that on the record later, I thought: “Hey, I said that.”

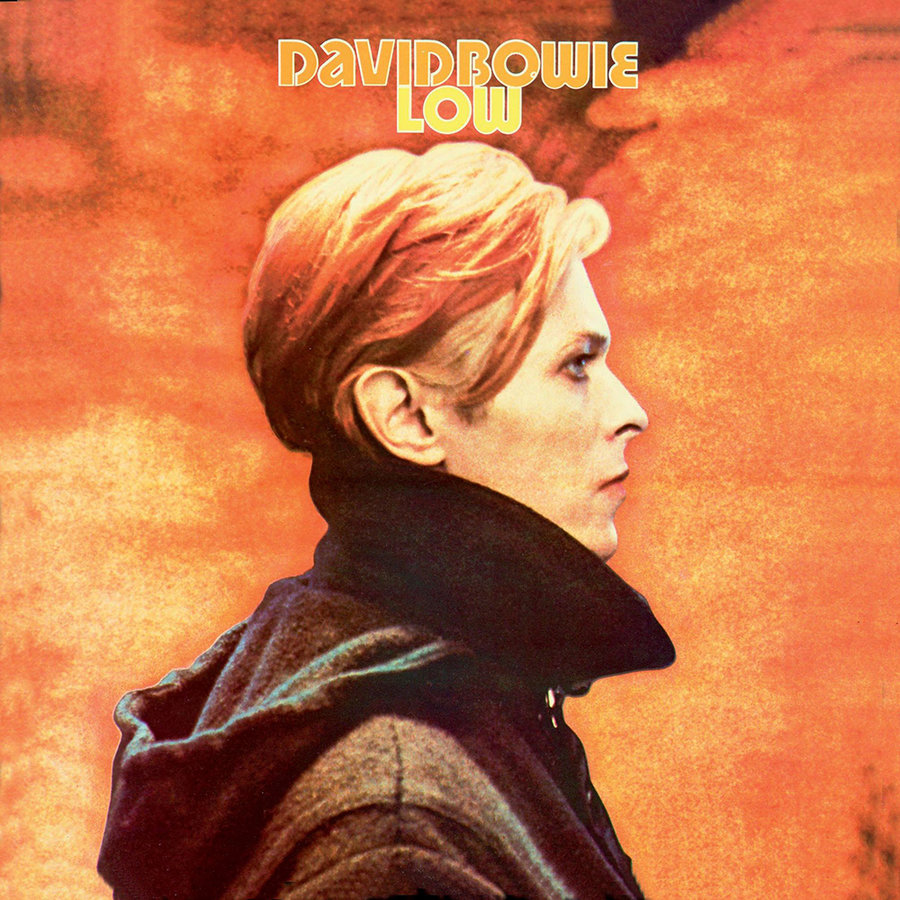

So, I did the painting. And then, they used the same image, which was a Steve Schapiro’s photograph, for the cover of the Low album. It was coincidental. When I was doing the cover, they gave me the opportunity to look through all the stills of the film, and little did I know that they were going to use that on Low, but the other way around.

I would like to have been involved in that one. But with David we never fell out, we were always friends.

Did you follow the later album covers, thinking whether you could have done it differently?

I didn’t think of it like that. Actually, I do that with every album cover, I think. But no, they were all pertinent to the songs and the way that he was at that time. I had no regrets that I didn’t do any more for him, really — I’m just happy to do the few that I did.

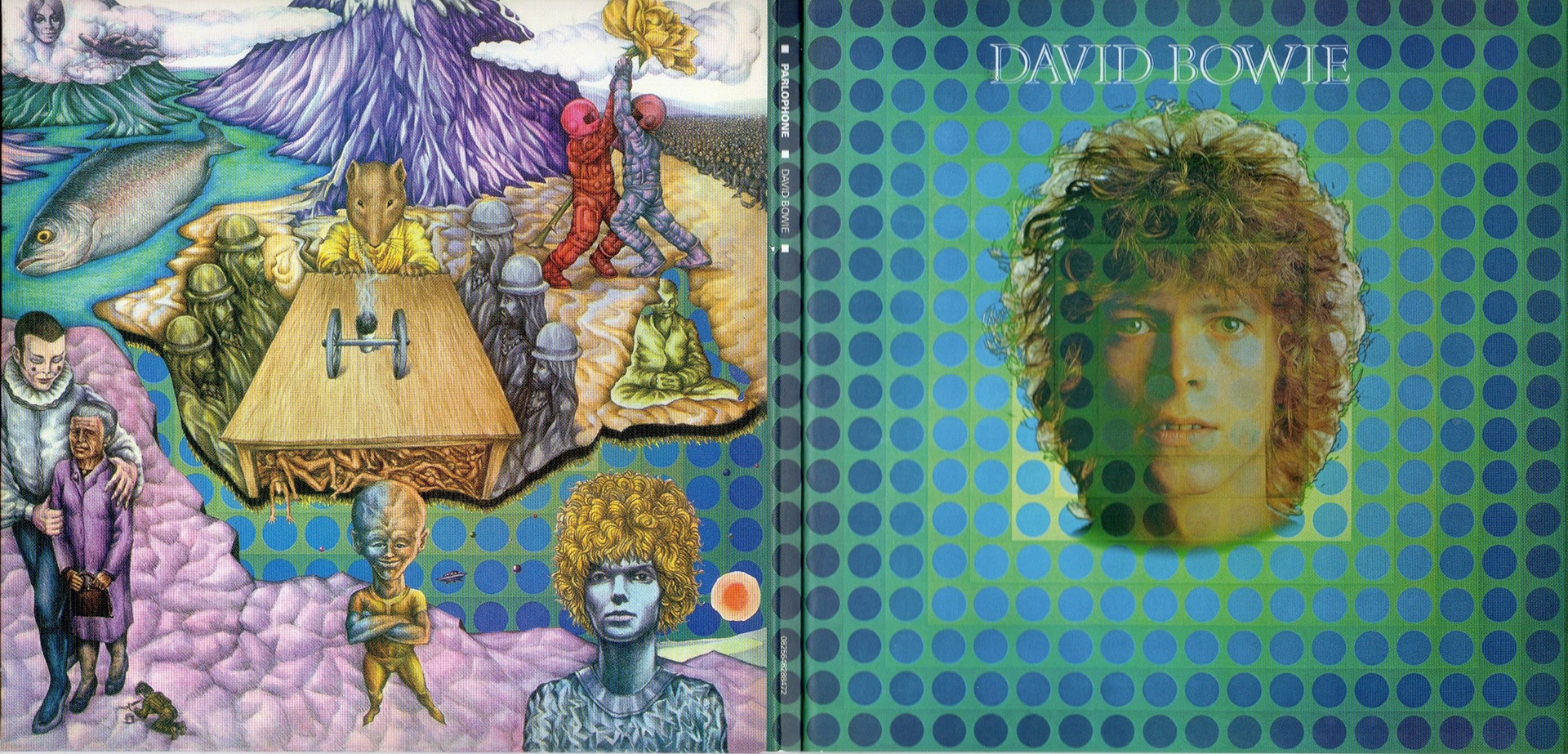

I think, our most interesting one was the very first one, with all the stuff on the back cover. Because that was really David’s art direction, and my interpretation of his lyrics. That was much more fun to do. And again, there was only about a week to do that. In David’s original drawing that he gave me there were many more things that he wanted in, but I said: “David, I got a week to do that, I can’t get them all in!” So, a few things were out.

I said: I got a week to do that, I can’t get them all in.

How you talk of David that he always knew exactly what he wanted to do resonates with Steve Schapiro’s words about how he came to his set knowing what he was exactly. Was the sense of him always like that, knowing what he was and what he does?

Yeah, he is very confident in his approach. Actually, not true, I just realized that sometimes things happen serendipitously. Something comes out of the blue that you don’t expect, and then: “Ah, I think I’ll do it that way.” David was never predictable, he would take a bit from there, and a bit from there, he would mix and match things, which other people wouldn’t dream of doing. Which made him unique, he was putting things together, finding new material and sources of inspiration from the most obscure artists sometimes that they would find from god knows where. And he’d say: “Oh, listen to this!” “What on Earth is that?” “I wanna put some of that in my new album.” “Oh, okay.” And it would work somehow.

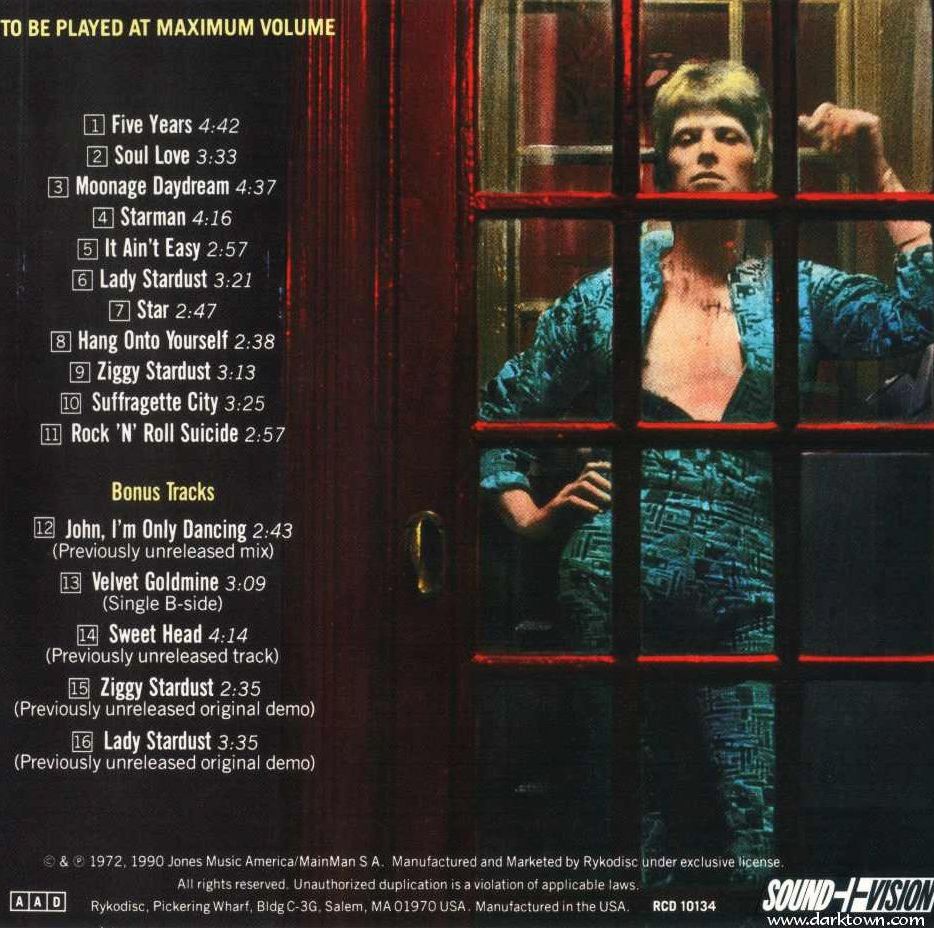

David introduced me to Charlie Mingus’ songs, he’s been dead many years now, he was a double bass player, jazz musician, really avant-garde. And he had a song on his Oh Yeah album, Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am. And one time David said: “I got us a new song I’ve just written” — he stood up with a guitar, started singing Suffragette City, tee-de-de-de, And then I shouted out: “Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am!” And he said: “That’s great, keep that in.” I got no credit for that, of course (chuckles). It was because of him that I knew about the song, so what goes around comes around.

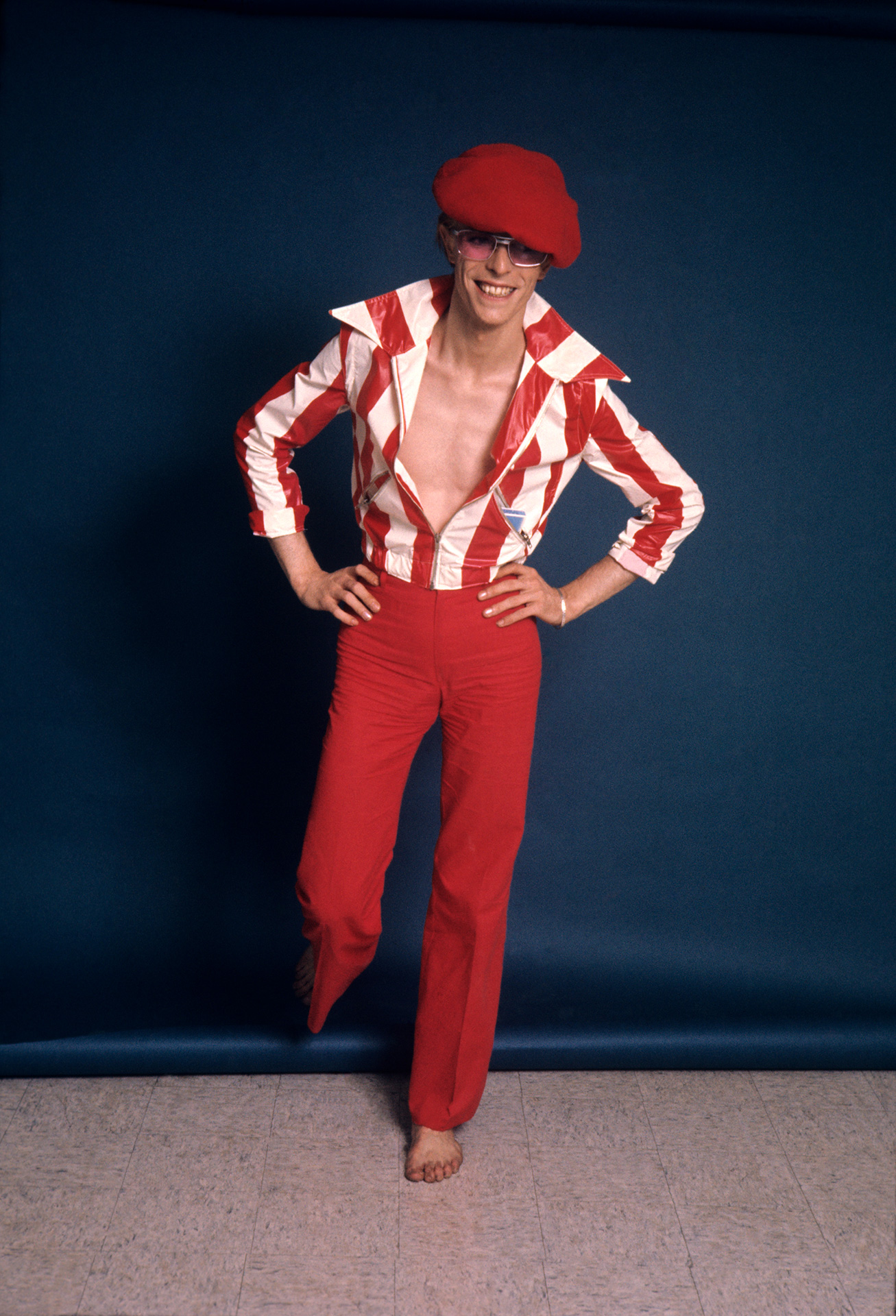

I sometimes see the importance of Bowie’s photos from Hunky Dory and The Man Who Sold the World discussed by LGBT people, in terms of how they were a rare example of a different attitude to gender at the time. Was it an agenda for him?

He might have had it in the back of his head that there were kids out there who weren’t quite sure of their sexual identity. And he kind of opened the door for them to feel better about it. When Starman was on top, everyone was talking about it, how he put his arm around Mick Ronson and that thing. You got to remember, he went through a phase when he was doing his mime show, he joined Lindsay Kemp’s mime studio. Lindsay Kemp and him had this affair, apparently. So, David went through his feminine side and all the other things.

There is always the other side of the coin with all this macho culture. When David toured the States in 1972, they were a bit worried because of this tag, ‘fag’, ‘fag rock’. It was a lot of homophobia over there, they didn’t like this fact that this guy was walking around ‘looking like a girl.’ I think, one of the days was cancelled in Texas somewhere, because they knew there might be some trouble.

Was it different in Britain?

It took a while. Because there was always two camps, one that would say “He is the most amazing thing that has ever came along,” and there would always be the other who would say “He’s not very good.” People took a longer time to warm to David. Mom and Dad would go: “Load of rubbish.” My mom used to say that about the Beatles, but later on, she loved the Beatles. They warmed to him in the end. And I think David has reached more people than he ever could have imagined. Three or four generations of people love David now.

“Oh, listen to this!” “What on Earth is that?” “I wanna put some of that in my new album.” “Oh, okay.”

David later worked with Lindsay Kemp, as Ziggy Stardust.

The thing in Rainbow, is that what you mean? They did a lovely show.

It is wonderful how he acts as a collector. He sort of took things from everyone he met and everything he saw and put them together.

That’s right. But he really did it in such a clever way, it wasn’t just throw-together. He really did it in a sophisticated way. But yeah, here you have French chanson, and there is Gustav Klimt.

There was one painting in his collection that he said he could get the same feeling from that painting as from a piece of music. Comparing art and music together was a sort of stimulus.

Do you feel the same way, because you’ve done both music and art.

I don’t do music anymore. I enjoyed it while I was doing it, but it didn’t like me. I always wanted to paint anyway. Of course, the only way you could make money as an artist in the old days was by being a commercial artist, but all the time I was doing album covers and book jackets, I was always painting as well, for myself. Knowing that one day I would hopefully be able to put the commercial side aside and just paint. And that’s, fortunately, what I do now. Hey!

You once mentioned that after Bowie died you couldn’t bring yourself to painting.

It was difficult. Because emotionally I was drained. My wife had to go off to Denmark, her brother wasn’t very well, I was on my own for about a week. And I did a painting, it was called The Angel Returns. That was kind of a metamorphosis, I got through that period and came out on the other end.

Do you still paint angels?

I’ve done a few. I got a show coming up in June, I could think of some new paintings to do — might be an angel amongst them. People like angels. I like angels. They can be feel-good or feel-bad, I guess, but we’ve all got our own guardian angel, which I kind of believe.

Your works seem a lot like Renaissance, which was very religious.

But I am not particularly religious. I like to use the word ‘spiritual’ rather than religious. Most of the Renaissance paintings were paid for by the church anyway, artists were just told to do religious subjects, so that was what they did.

When I do a face painting of someone I made up in my imagination, I want them to have an expression on their face that makes people wonder what they are thinking about. I like the idea of people interpreting paintings in their own way. David said that there is a bit of isolation in my works. Well, that’s cool, I don’t mind that.

David used to paint himself, didn’t he?

He did. He took lessons from John Bellany, a Scottish painter, by the way — David bought a few of John’s works, and John offered him painting lessons in return.

Bowie once said that he didn’t become an artist because he saw you painting and it was so good.

I don’t want to be cruel, but David wasn’t cut out for it. He did okay in painting, but his heart was in music, it was where his passion lied. David’s passion for music was rather a tsunami. Painting was something that he would do if he had spare time.

I wonder how he became this phenomenon, how you can look at a photograph or clothes and say “this is Bowie-like.”

Yes. He’s become iconic, very much so. It is difficult to put a finger on it, it is not an easy one to put in a category. David had his own category, his own persona. And I haven’t seen anyone else who comes anywhere close to David. He would stretch himself as far as he could in every direction. There is a lot of space to fill since he is not with us anymore.

David’s passion for music was rather a tsunami.

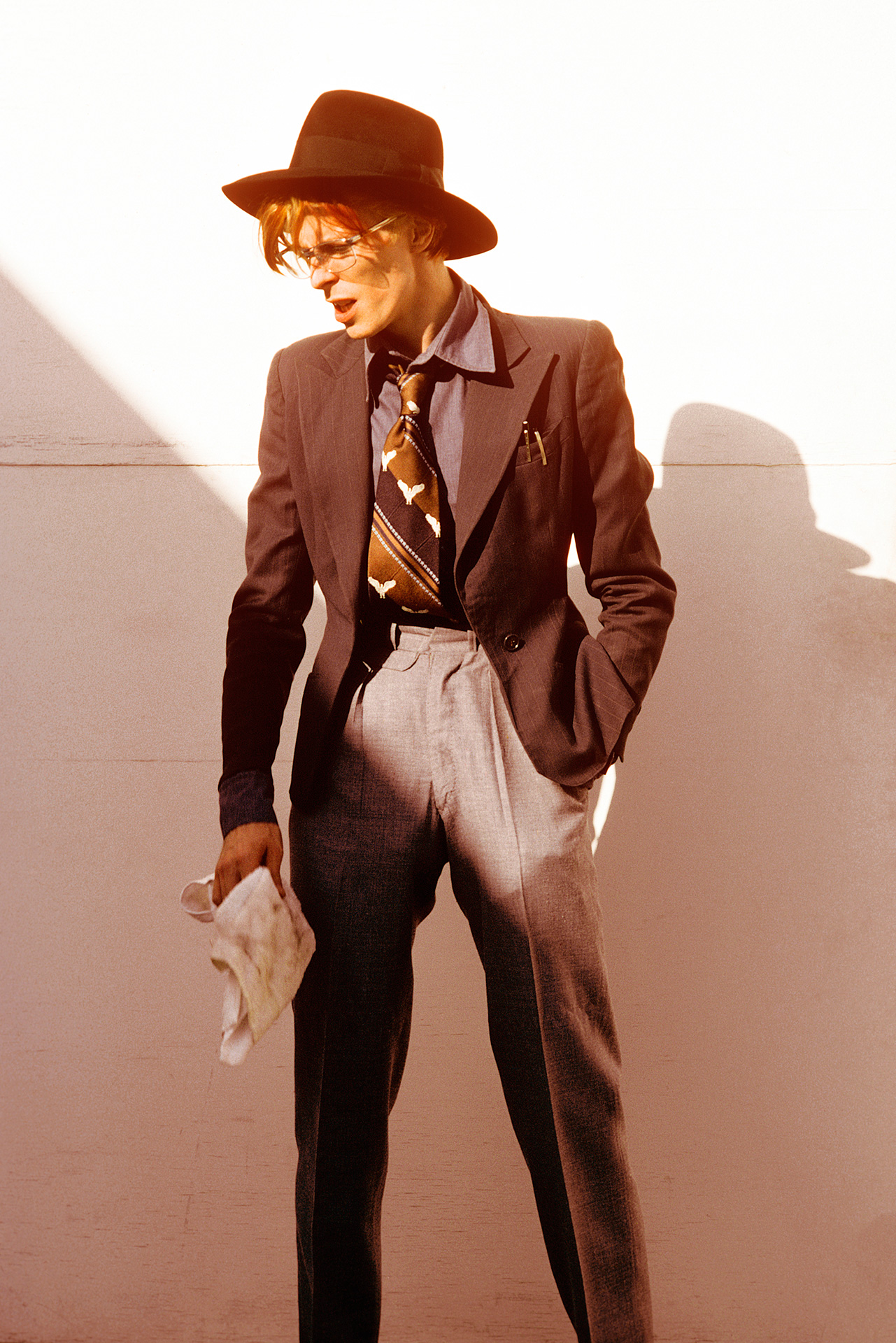

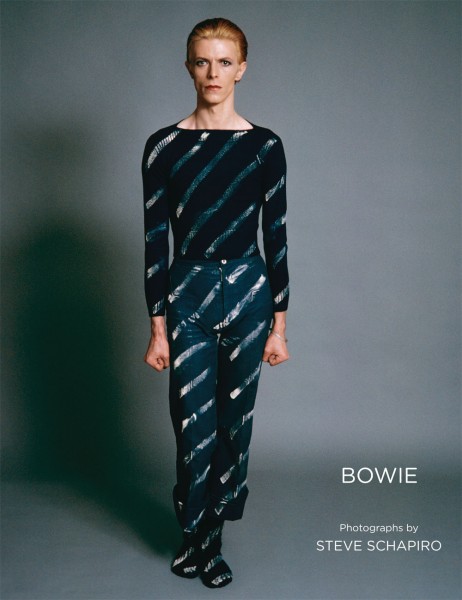

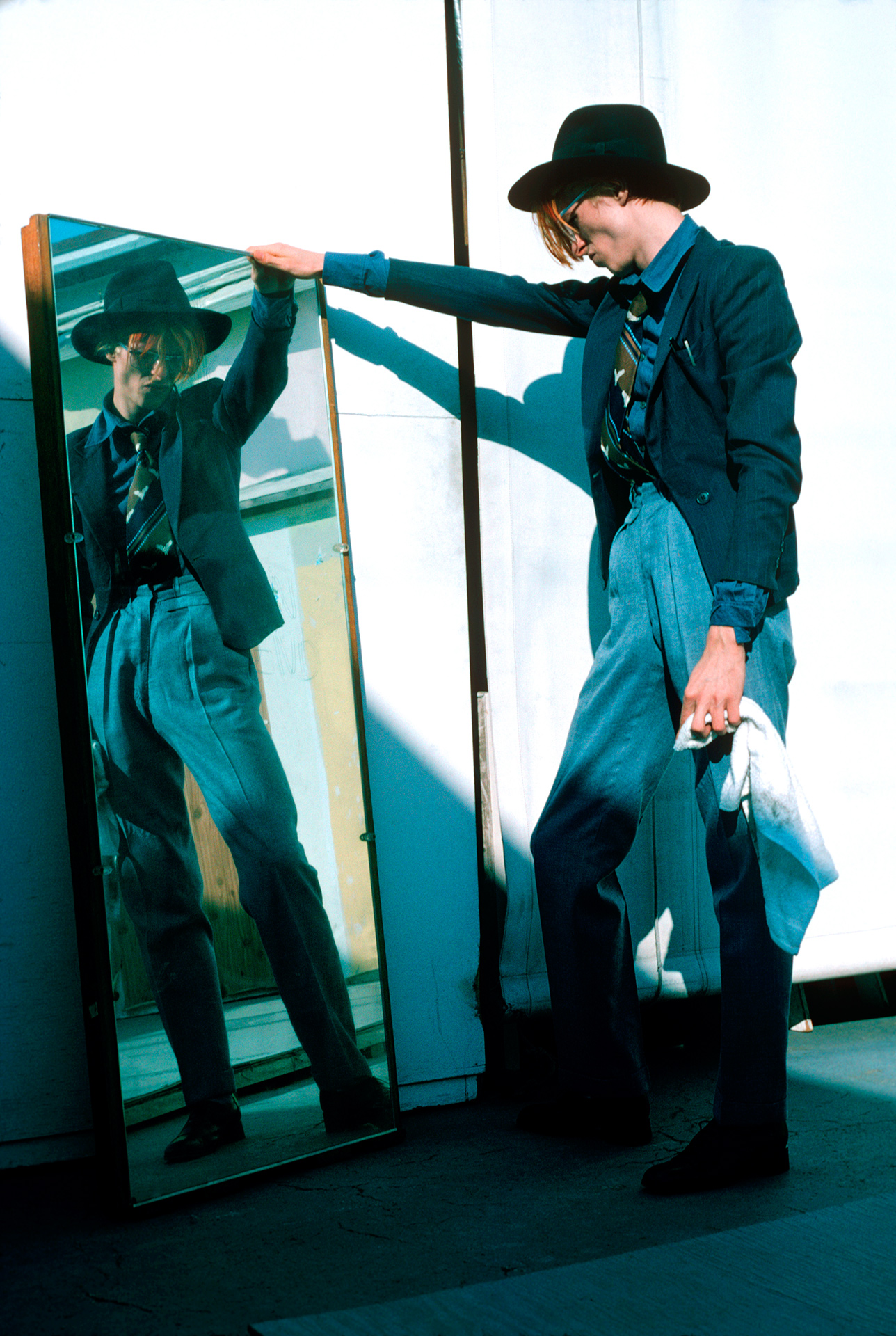

Photo: Steve Schapiro

Photographed the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the Selma to Montgomery march; was a photographer for films such as the Godfather, Chinatown, and Taxi Driver; took portraits of Jackie Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Woody Allen, and Frank Sinatra. Worked for Life, Look, Time, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, Sports Illustrated, People, and Paris Match. In 2016, released a photobook called Bowie with photographs taken in the 1970s.

Was shooting Bowie different from shooting other musicians?

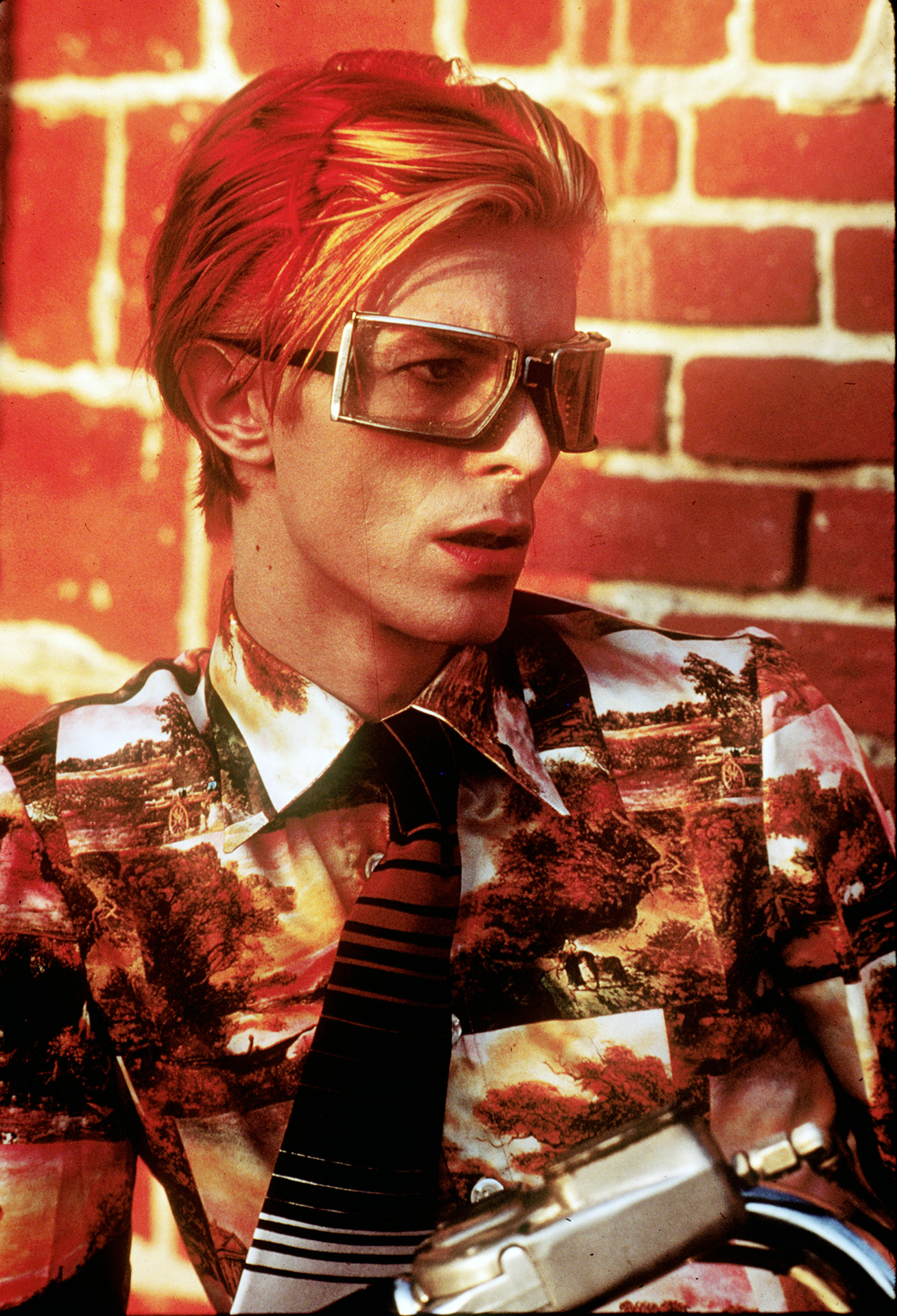

It was a surprise. I knew David Bowie for his flamboyant costumes and his vigor. He came to the studio at 4 o’clock and we didn’t know what to expect. And he came with these incredible, colorful costumes, but the first thing he did, he went to my assistant to borrow his blue cropped sweater, went to a dressing room and stayed there for about 20 minutes. And finally he came out looking like the image from the cover of this ‘Bowie’ book, which he painted himself, with the stripes. And then, he went to the background and pictured circles and figures. Finally, on the background floor he drew tree of life of the kabbalah. Basically, the whole look was a spiritual thing.

Did he explain to you what he was doing?

No, we never talked. It would have messed with his concentration on what he was doing, he would be thinking about our conversation, instead of doing what his soul could do.

Basically the way I work is usually very quiet. The moment I get into a conversation with someone, they’re thinking about me and what they should say to me, and they are not thinking about who they are as a person.

This costume later appeared in the ‘Lazarus’ video. Did you see it before or after he died?

I saw it after. I was not aware, as most people weren’t, that he was very sick. (Bowie supposedly learnt that his cancer was terminal about a year before he died; and he told only the closest people about it. — Ed.) I couldn’t have helped noticing that he went back to that character right before his death. I think, this was not a coincidence: then, David discovered something that was important for him or for the person that he was yet to become.

In your earlier interviews you said that when he came to your shoot, he ‘knew exactly who he was’. Who do you think that was?

I think he was a person who always knew who he was. And what I find in Bowie is his enormous growth, as an artist and as a person. With every character he created, he grew as a person along the way. And he was a very smart person, with unique intelligence in every way.

With every character he created, he grew as a person along the way.

Would you say that this shoot was also iconic, like your photographs of Martin Luther King or Jackie Kennedy?

I think it was definitely iconic. especially those with this kabbala drawing on the floor or the photos we took in New Mexico when shooting The Man Who Fell to Earth (also included in the book). That’s the way others think about them as well, putting them on display in museums.

Bowie himself was definitely an iconic person, and his influence is still there — after he died, albums inspired by him were released, and I think will continue to be released.

You previously said that portraits of pop culture figures not only say something about themselves but also about their era. What might these photos tell us about the 70s?

I think that it was a time of music and a flamboyant time. But I also think these pictures are more personal. Particularly in the last pictures in the book, where he is just sitting with his fingers crossed.

We worked through different ideas during that shoot — he tried on some costumes, wrote something on the mirror. You can see him create his public persona. You know that David Bowie is not even his real name, he created a character.

Many characters.

Yes, many characters. And here we can see how his incredible mind works, this internal work that is going on.

Steve Schapiro’s exhibition David Bowie. The Man Who Fell to Earth is open at the Lumiere Brothers Center for Photography in Moscow until March, 31.

New and best