“It Took a Mere Day to Return Us to the Medieval Era”: Serhii Ristenko’s on Three Weeks Spent in an Occupied Village in the Chernihiv Region

Photographer Serhii Ristenko lived with his wife and two kids in Kyiv. When the Russian invasion began, his daughter was recovering from a leg injury. Since it would be hard to move quickly between their flat and the basement on crutches, the family immediately decided to move to their cottage in the Chernihiv Region. There, in Novyi Bykiv (about 90 km from Kyiv), they planned to catch their breath and decide what to do next. Mere days after their arrival, Russian troops occupied the village.

Photographer. Lives and works in Kyiv.

“Everything was calm at first, and we even made a rough plan of what to do next. However, a Russian tank column entered the village on the 27th of February. We counted about 1,000 military vehicles and armour in total. There could be fewer of them, though, I think. Anyway, the column took a few hours to pass. It all began at noon with an explosion when the Ukrainian troops blew up a small bridge near the village. But it was useless. With the same effect I could have armed myself with a utility hole cover and said, ‘This tank shall not pass.’ I mean, it didn’t stop the tanks from entering the village. There were 6–7 people from the Territorial Defense Forces there, and they got immediately killed. The Russians used a fence to cross the blown-up bridge—they just took it, laid over the bridge, crossed it, and opened fire on the village.

A Russian tank column entered the village on the 27th of February. We counted about 1,000 military vehicles and armour in total. There could be fewer of them, though, I think. Anyway, the column took a few hours to pass.

Everyone hid. There was a two-storey panel house with a basement near our cottage—we spent a few days there. I joked that while men were occupied with trifles, discussing Russian hardware, women smartly decided to clean up the basement, which had been neglected for 40 years. Although we managed to tidy it up a little, the damp, dark, and cold basement wasn’t that well-suited for living. Electricity, gas, running water, and communications were down on the very first day of the occupation. Having spent two nights in the shelter, we all fell ill—the temperature outside was still below zero, and it wasn’t that much warmer in the basement.

When the cell service was up again sometime later, people wrote me something like ‘Let’s message not over SMS but on Viber or WhatsApp.’ It was ridiculous. And I went, ‘It takes an eternity to send even an SMS here, can’t you understand?’ They even offered to send some money to my card. But what could I do with it? All local shops were immediately destroyed and looted. It took a mere day—the 27th of February—to return us to the Medieval Era.

When the heavy fire stopped, we returned to our house. However, we hardly left our yard at all during the first week. We removed the fence between our yard and our neighbours’ for everyone to move without going out in the street. I joked that it was our local Schengen zone.

We didn’t learn about the rules established from the beginning of the occupation until a soldier came to our area a week later looking for cigarettes. He explained that anyone walking the streets had to have a white band on their arm. Also, only women were allowed to approach the military and ask them anything. Any man spotted outdoors, or a car that tried to leave were shot on sight. As a result, there was no way of communication between the different areas of the village—you couldn’t even cross the street to learn what was going on there.

Any man spotted outdoors or a car that tried to leave were shot on sight.

Later, they relaxed a little. After all, people had things to do outside their homes, too, like chopping wood—it was cold, and there was no gas. We were lucky, by the way: the house was rather a summer cottage for us, so we didn’t install heating there, preferring to heat it with firewood if needed—that seemed nicer. However, we started running out of wood, and we had to chop it somehow. Moreover, we even had to ask permission at the Russian checkpoint to use a chainsaw.

The military drove out people from some houses and started living there, parking their tanks and IFVs in the yards. We had another cottage elsewhere in the village, which we had been rebuilding over the prior year. It was in that area where they ousted people, and they settled in our house, too. There is a small forest near our house—they put tripwires everywhere there.

People took in those driven out of their homes, so 10–15 people lived in the houses near ours. It was cold. People could sleep fully clothed on rugs and use another rug as a blanket.

The village council did nothing—they all just fled who knows where. There was no village head. Nobody. The former one went to the Russians to negotiate and explain that locals needed medications and such. They answered something like ‘Put your hands behind your head and go home, gramps’, and that’s where any negotiations ended.

The Russians set up their anti-air defence positions in the school and the kindergarten. A Russian Buk was firing close by—we could see its rockets from a few hundred metres away. We eventually got used to it, though I still don’t get how one can get used to something like that. As the situation got tenser, they started firing more often.

A week before the war broke out, we stockpiled some food. Even if we didn’t need it immediately, we figured it could remain at our cottage. Despite that, we had only the potatoes stuffed with potatoes with a potato garnish toward the end. Neighbours helped a lot. It’s a village, after all, and life didn’t stop there. Those who had a cow shared milk; others shared salo or whatever canned food they had; we gave our flour—everybody bartered. We baked bread in our oven to sustain ourselves. When our kids fell ill and we had no medications, everyone in the village helped us find whatever we needed. And when we ran out of pills, all kinds of traditional medicines followed: raspberry and elderberry jams and such. We had some drinking water stockpiled, too, and used melted snow as utility water.

When our kids fell ill, and we had no medications, everyone in the village helped us find whatever we needed. And when we ran out of pills, all kinds of traditional medicines followed.

We had a children’s electrical kit, and I managed to assemble a battery-powered radio from it. It had one channel, but there were news reports there. So, I went outdoors twice a day, sat on the bench, and told the news to people from the two or three neighbouring houses who gathered near me. I saw that everyone was devastated and tried to cheer them up, recounting how much enemy hardware was destroyed and where the invaders were pushed back. I kept the worst news to myself. It would have changed nothing if I told them, I guess, but it was easier without them. There was some heavy censorship on my part, but I needed to keep the people’s spirits high, and it worked. As a result, I became the best buddy even with the old ladies who used to gossip behind my back. Everyone asked about the latest developments.

So, I went outdoors twice a day, sat on the bench, and told the news to people. I kept the worst news to myself. There was some heavy censorship on my part.

Local news was spread by word of mouth by the people who went somewhere and saw something. However, those had to be thoroughly filtered. On the first day, for instance, they said that the Russians entered the nearby village of Staryi Bykiv, dragged all the men out of their homes, and killed them. However, 90% of the killed were miraculously alive by evening.

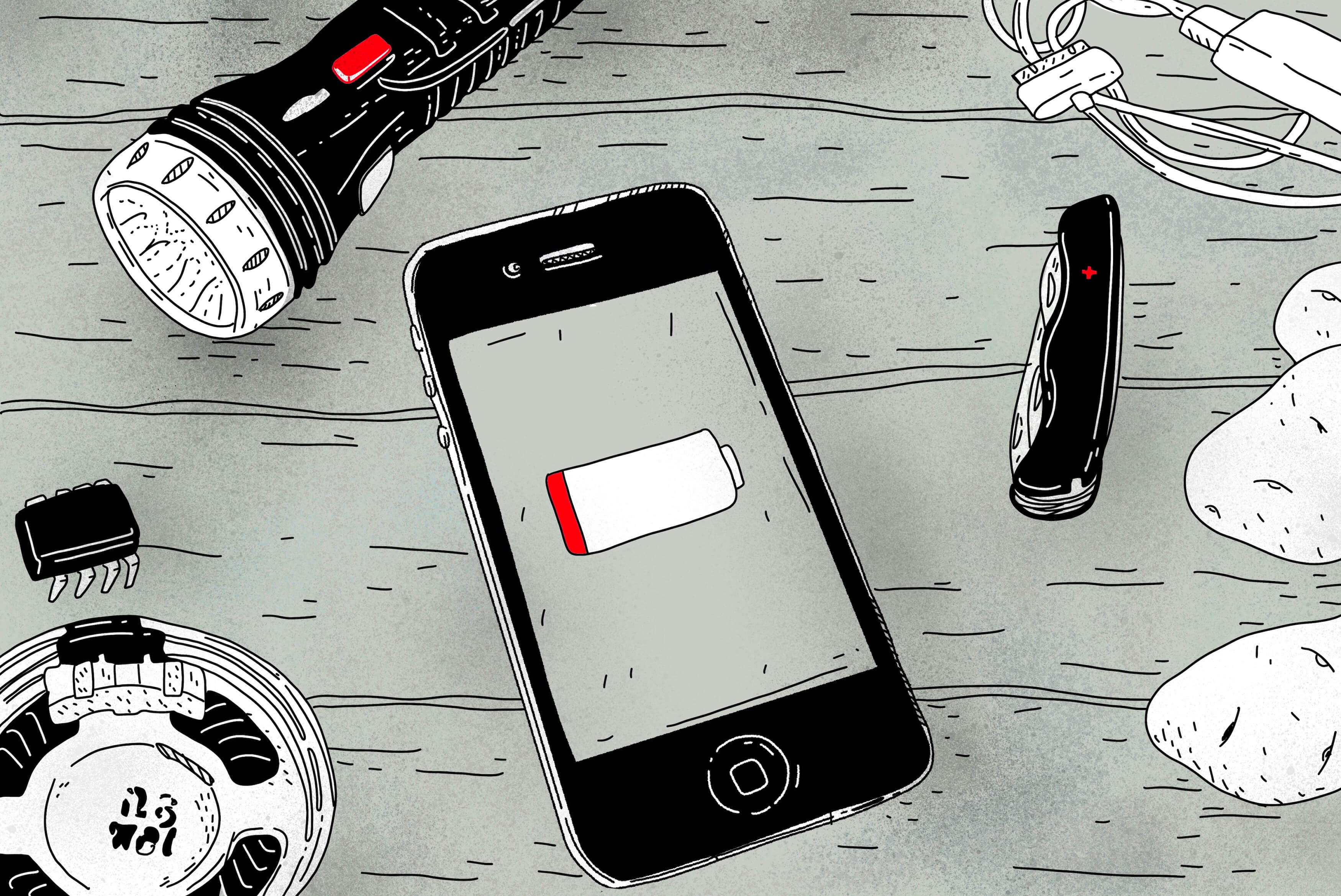

Although we had some of those fancy smartphones, they couldn’t hook up with the mobile network and soon ran out of battery because there was no way to charge them. But I had an old iPhone 4 on me, and it kept working. Granted, it showed cell connection only two weeks later, and nobody even knew that we were alive before that. Some of our friends considered us dead, it seemed. Therefore, when I managed to send an SMS, I asked them to write on Facebook that we were alive but otherwise up sh*t creek without a paddle. I was careful, thinking that the Russians could intercept my messages, so I wrote nothing concrete and then immediately deleted them. When someone wrote to me and asked for a precise address, I told them to shove it, and for a good reason. The very next day after we left, the neighbors who stayed told us that the Russians were looking for us. They went from door to door in our area, asking where we were and checking everyone’s phones.

I prayed to God that the locals didn’t turn me over. Some of them were somewhat friendly to the Russians. Also, all locals knew that I had a drone because I used to fly it all the time earlier.

Sometimes people asked me if I could take pictures of the enemy equipment. I answered that I could, but nobody would get the photos, while my family would get me in a plastic bag. I mean, I couldn’t go out in the street because they shot men on sight, much less point my camera at the Russian tanks. The instincts kicked in, and I kept thinking about my family first. Once, my wife and mother-in-law came under the machine-gun fire—they went to get some water, but soldiers saw something fishy about them and opened fire in their direction.

Sometimes people asked me if I could take pictures of the enemy equipment. I answered that I could, but nobody would get the photos, while my family would get me in a plastic bag.

I realized that it could drag on for weeks, but kept waking up and thinking: ‘What a nice sunny day. People usually don’t die on days like these. And in the evening, I thought: ‘We have survived through this day. We are alive and going to sleep, and that’s our main achievement.’

We are a nation that can get used to anything and set up any kind of system if the circumstances call for it. Once, we even invented a scheme to deliver insulin for children from a nearby unoccupied village 5–10 km away. The Russians were moving as a column, so the villages near ours were still free of them. The Russians checked everyone passing the checkpoints but let those carrying medications through. So, we had even a working smuggling scheme toward the end.

Soon, Ukrainian troops approached and started shelling the Russians. It became dangerous to be outside because something was exploding all the time. From what I gathered, the armor columns that exited our village were immediately shelled. The eye-witnesses said that Russian soldiers were growing angry. They refused to let people out of the village and only started letting them through in the last few days of our stay—first on foot and later in cars. On the first day that the evacuation was permitted, they could even seize the car at the checkpoint and let people go on foot only. They also could take whatever else they found: phones, tablets, etc. Soon, half of the households on our street evacuated—some even managed to contact us later to tell this. At first, our neighbors said it was too early to leave. One day, however, they knocked on our door at 6 a.m. themselves and said that we should leave at once because the word on the street was that the sh*t would get real soon. So, we decided to try our luck.

It took us three hours to get from our village to the next one, although it is usually a ten-minute drive. We passed four enemy checkpoints. I noticed that the soldiers were young, like aged 18 to 23—juvenile looters, no less; some Buryat guys, I believe. And they were scared sh*tless, pointing their rifles in the direction of any noise. It was scary and felt totally like a one-way trip.

We put white bands and all these ‘Children Inside’ stickers on our car, opened windows and drove really slowly. When we reached the Russian checkpoints, Ukrainian forces opened fire, so everyone there got out of their cars and took shelter in the nearest basement. At that moment, I hoped that our guys would switch to some other target, lest our trip comes to a grinding halt. Fortunately, that was precisely what happened—they switched to an armor column, and we managed to get away. Meanwhile, the Russians searched the abandoned cars, albeit taking only a knife, a torch, and an iPhone cable in ours. Eventually, we got further away and entered the grey zone.

At the Ukrainian checkpoint, soldiers asked us to remove the white bands and stickers not to scare locals because we were entering a peaceful village. So, we enter the village and see people wearing masks enter the shop. I remembered how we joked during the first days that everyone had forgotten about COVID-19. It was a kind of cultural shock for me. I spent 20 or 30 minutes sitting and watching people enter the shop. There were groceries there and electricity. The usual life a mere 15 km from the ghetto we lived in. At the car wash, which I regularly visited, I saw an operator I knew. ‘Hey, hello,’ he greeted us, sipping coffee. ‘How are you? Managed to get out, eh?’ Yup, we managed to get out.

We spent a night at our friends’ place there and went to the Western part of the country, as the children’s safety was above all. All that time, I tried to laugh it off, to make it less scary for children: ‘You know, kids, we are on a long family trip now. We are behind enemy lines, so we have nothing now, and our primary task is to survive and not get caught.’ It worked at first, but the children were on the verge of hysteria toward the end. My older girl, who is 11, kept sleeping in her clothes with her backpack at the ready. Hearing any noise, she immediately rushed to the door. My 5-year-old boy keeps drawing pictures about war, even though we have made it to safety already. They fall silent at the sight of a helicopter and fear soldiers. Hopefully, it will go away soon. I don’t know anything about the situation in Novyi Bykiv—most people have left the village, and there is no way to contact anyone there.

‘You know, kids, we are on a long family trip now. We are behind enemy lines, so we have nothing now, and our primary task is to survive and not get caught.’

I remember reading books about war when I was little: something about Volodia Dubinin, Kovpak’s ‘From Putivl to the Carpathians’, and such. When it all began and tanks entered the village, I thought that I was like a character from those books, a guerilla fighter. In general, reading books and chopping wood were the two things that kept me going. After all, I had to stay indoors and had nothing else to do. I had to calm myself not to show all that stress to my children.

It was as if we had returned to primitive times. Like our ancestors, we went to sleep at 8 p.m., because it got dark and electricity was down, and woke up at 5 a.m. or 6 a.m. at dawn. All my dreams were about peaceful life, by the way. And here, once we got back to civilization, I started having nightmares and problems falling asleep overall. In a word, it has been a peculiar experience. I think it has left me with a bit of grey hair. I also kept a journal there, writing there every day. It helped a lot, too. But I won’t open it again until some time later.”

Illustrations by Ira Rohmb

New and best