Myths of the War in Kateryna Lysovenko’s Paintings

Victims, violence and power have long been present in Kateryna Lysovenko’s art. She reflected on the Soviet’s heritage in modern paintings, manifestation of ideologies in monumental art, and the way victims are depicted by Ukrainian and international artists. The full-scale Russian aggression against Ukraine filled the old topics with new meaning.

Artist. Studied at Odesa Hrekov Arts College, National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture (Kyiv) and Kyiv Academy of Media Arts. Her works are presented at Voloshyn Gallery. Before the war she lived in Kyiv, now she lives in Austria.

— Right before the war, my consciousness split into two parts. One part — the one, which knows history and understands the way fascism develops — realized that the war was inevitable. Another part could not take that. It was too horrible, illogical, and irrational to comprehend. On 23 of February, my fear had suddenly disappeared and I wrote in my diary: “a grave disaster is catching on me, but I’m breathing easily.”

When the war started, I was at home. We woke up to the sound of explosions in Kyiv. That morning we packed in half an hour, woke up the kids, and set off on an exhausting journey. Firstly, we went to a small town near Kyiv, then — to Lutsk and Poland, and in a month we moved to Austria, where we stayed for now. When we were in Poland, I was close to psychosis. Now I’m getting better. But my vision has changed. I look at the peaceful cities and see how fragile they are. I keep thinking how fast can peaceful living come to an end.

Once I was in Poland, I started painting. For me, painting is something like a second voice or an additional language. It helps me realize and live through whatever is happening. At first, I was drawing because I just couldn’t help it. Back then, critical thinking was not the case, I just needed to express my emotions. Afterward, I thought about my paintings and felt devastated. I have been working with trauma, violence, and dehumanization for a long time. Like many other Ukrainian artists, who work with a heavy historical context, I couldn’t indulge myself in merely exploring the artistic form. Shortly before the war, I thought that I had spent enough time examining the historical trauma. I started looking for the next thing to explore. And that very moment the trauma came back — bigger and scarier than before — and it will probably stay with me forever.

In these works, I lean on my previous reflections — about utopia and the garden space, which means the space that was created by us and where we have things that we can control and those that we can’t. Take, for example, the garden cemetery. On one hand, it is a public place; on the other hand, it is a place of memory. Memorizing things that are happening now is crucially important. Our memory shouldn’t be artificially constructed like they did in the Soviet Union; instead, it should be composed of millions of separate reminiscences.

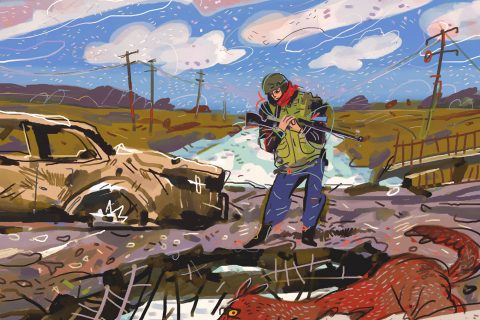

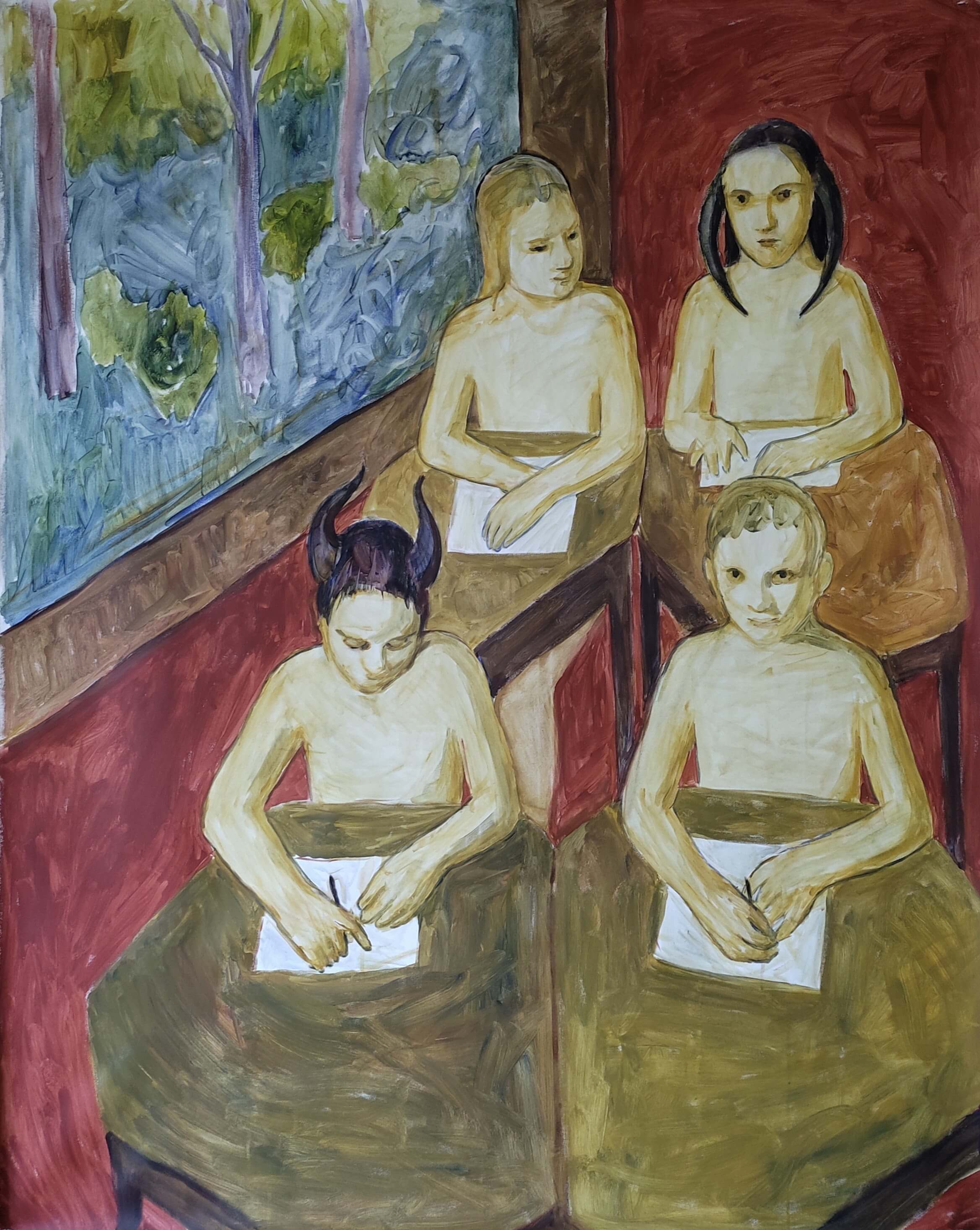

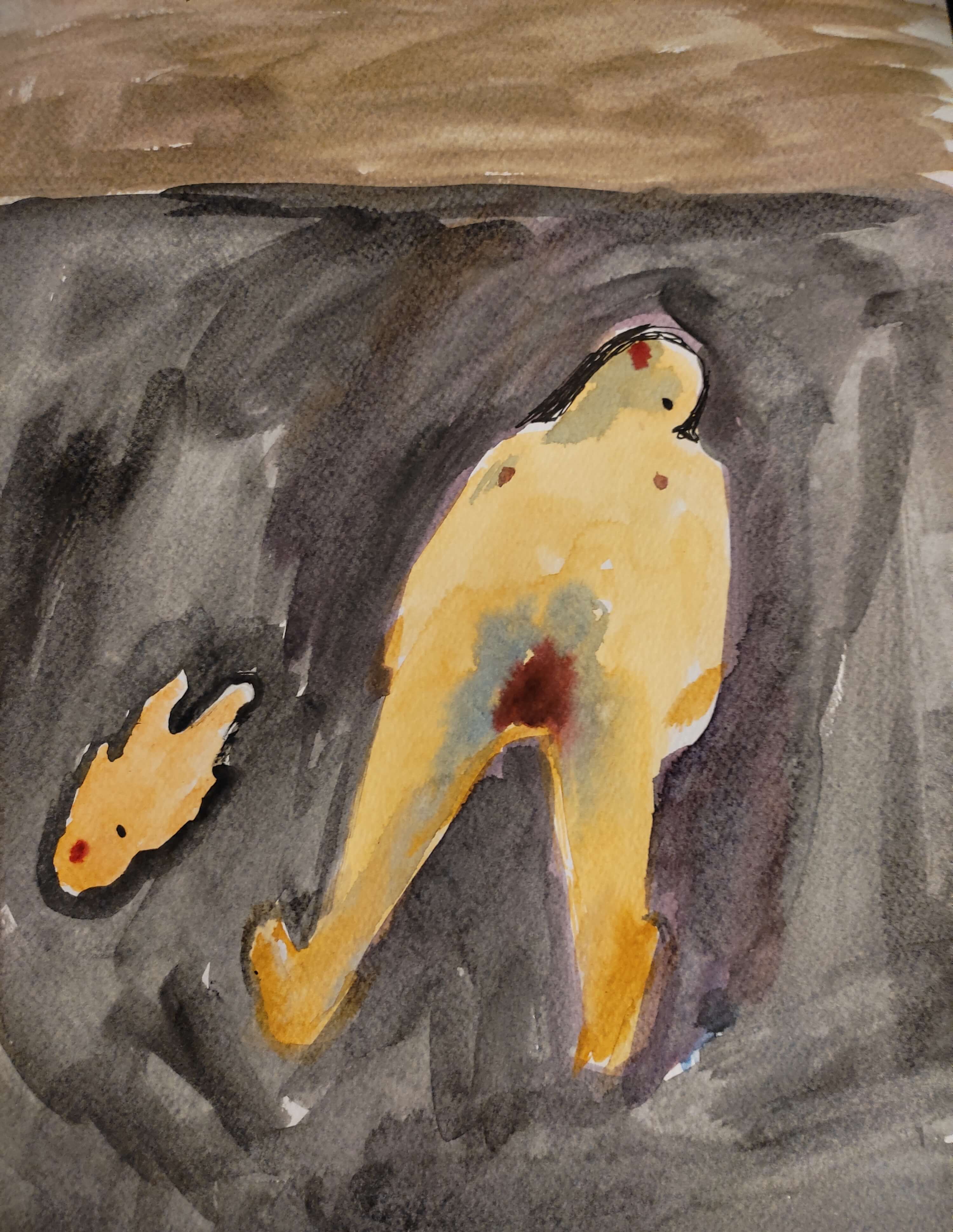

I love art because it gives me an opportunity to work with impossibility. Terror, death, and violence are something that cannot be realized or depicted. In my works, I keep using images of fantastic creatures, like centaurs or mermaids. The presence of myth helps me define the impossibility of the disaster. We can’t see the victims’ emotions in real life because now they feel nothing. But in the fantastic world we can think of complexity and beauty, of relationships and public spaces, like schools or nurseries. Besides, I’m showing the archaic logic of murderers. It is hard to kill a person that is just like you. At the same time, you can kill or sacrifice a monster, a centaur, a mermaid, a Nazi — someone, who’s different.

I love art because it gives me an opportunity to work with impossibility. Terror, death, and violence are something that cannot be realized or depicted.

I’m proud of our heroes — military and volunteers — but I deliberately avoid talking about them. Instead, I focus on those, who can speak no more — on the victims of this war. Every next crime was worse than the previous — raped children, murdered families. I was shattered but I also wanted to document those crimes to keep them in our memories. Take, for example, the painting with the dead mother and child. I wanted to show what was taken from those people, that horrendous theft. These paintings are my personal monuments to terror.

It scares me that people turn into statistics of dead and refugees. I try to bring their subjectivity back to them in my works. We haven’t reached the point when Ukraine had a chance to claim its subjectivity. We haven’t spent enough time reflecting on our past. I think that history matters. When people see photos from Bucha, they feel shocked. But this is not the first time that we face terror. It has been here before — in the 30s, in Chechnya, in Donbas. Russia knows perfectly well how to use terror. They break people down. They create situations when everyone is being watched and too afraid to speak out. Because of the fear, people start blaming victims. Because of the same fear, people become a part of the system.

I think that Ukraine should take responsibility for everything that we’ve done in the past. We have to admit that we had survived disastrous Russian terror. We have to admit that this terror had forced some Ukrainians into the system. Only after that can we claim back our cultural heritage of that time and our right to be called the country that defeated Nazism. We have to stand together with other victims of the Russian terror and speak out. The world needs to realize that history comes back in circles. Stalin’s terror becomes Putin’s terror; the Holodomor of the 30s creeps back to southern and eastern parts of Ukraine. Currently, we have no opportunity to come to Mariupol with human right defenders and photo cameras. But if we can’t see the crimes it doesn’t mean that they haven’t happened. In my works, I strive to recreate the tension and realization of the crime, whether we saw it or not.

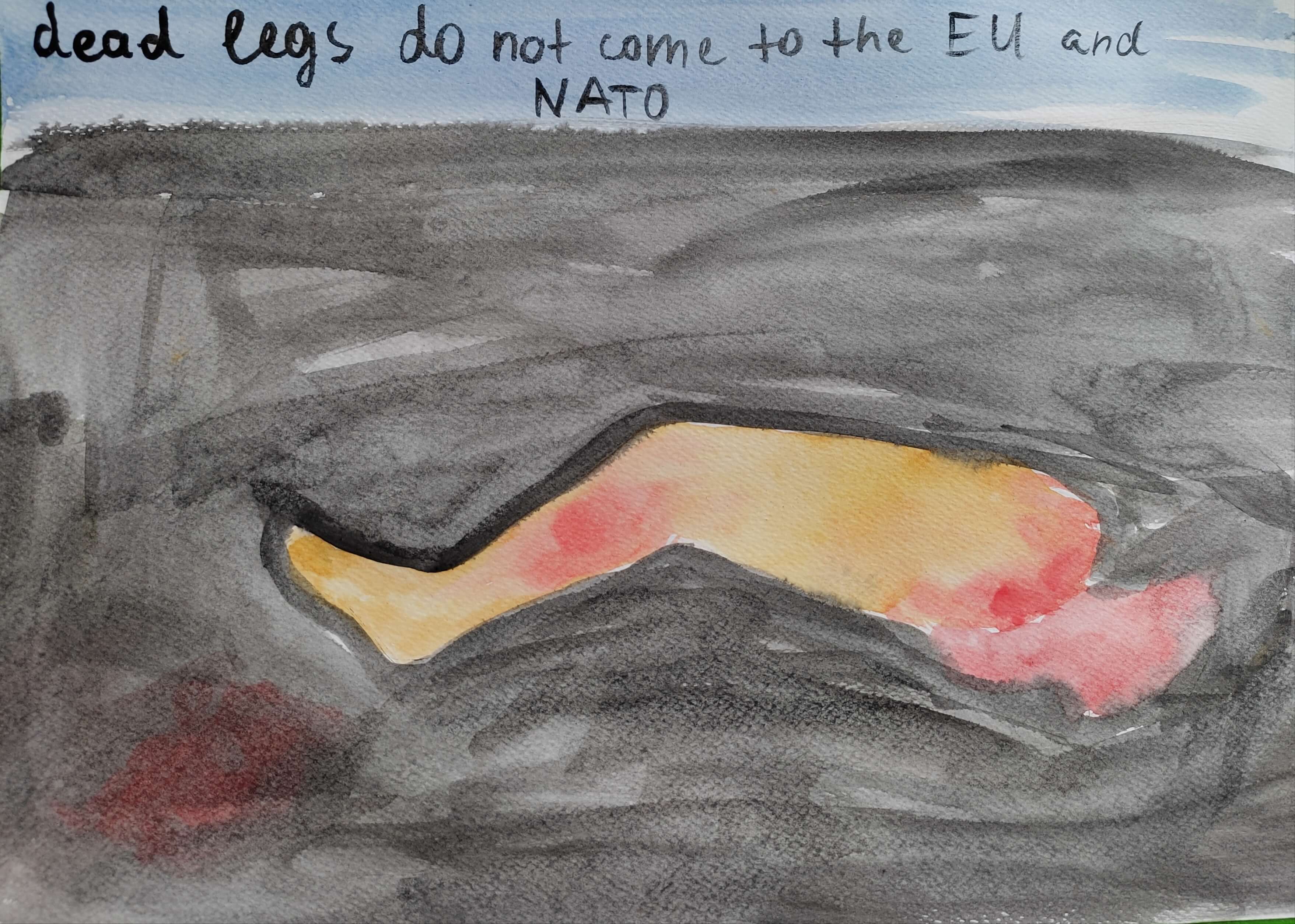

I have a painting called “Dead legs can’t walk to NATO”. It looks like an ideological poster, but I used that technique deliberately. NATO allegedly says that it helps us and waits for us, but it doesn’t help us the way we need it and can’t accept us if we all die. To me, ideology is the enemy of politics. But at the same time, it’s an instrument, and artists should know how to use it. If we understand it, we can leverage it.

If we want to make art about the Ukrainian context, we need to understand Ukrainian ideology and treat it critically. The war doesn’t make people better. Our society was deeply traumatized by the annexation of Crimea and creation of pseudo-republics. However, from time to time you could have spotted victim-blaming towards people who lived in occupied regions. Supposedly, people who spoke Russian had it coming. This is another outcome of terror. Our friends and neighbors get killed, and we search for explanations why it is happening. We persuade ourselves that, probably, they’ve done something wrong and deserved to be punished. Whereas we have done nothing wrong, so we should be fine. But there is no logic in the war that is based on ideology, not economy. Anyone can become a victim.

Our friends and neighbors get killed, and we search for explanations why it is happening. But there is no logic in the war that is based on ideology, not economy.

It upsets me that this escalation started at the time when we finally managed to build a less unsettling dialogue between eastern and western parts of Ukraine. As an artist, I see my role in preventing archaic thinking. This type of thinking can deepen the language conflict. If refugees from Kharkiv, who’s men bravely protect the city, are being bullied for speaking Russian, I don’t think that it makes us a democratic and pluralistic country.

As an artist, I see my role in preventing archaic thinking.

In my opinion, we shouldn’t dehumanize Russians the same way they do to us. We shouldn’t say that every representative of Russian culture, who’s speaking out against the war, is still a traitor. That’s the pain and anger speaking in us. And I don’t want us to become a nation, which rages and dehumanizes everyone around.

New and best