Denied Mexico: Life Goes on Behind the Heavy Curtains of Mainstream Reporting on Latin America

Born and raised in Ohio (US). Graduated with a degree in Biochemistry from Vanderbilt University and worked it this field for three years before turning to photography. Left for Mexico 29 years ago and is going to stay. Specializes in documentary photography, his works were published in Stern, Al Jazeera America, Der Spiegel, Newsweek, The Nation, Fusion, The Intercept, Financial Times, and The Guardian.

It became quite difficult to convince editors to take stories on Mexico, the last big project that I worked on was for Al Jazeera America — about striking women workers in the Lexmark Maquiladora, a manufacturing plant US, Chinese and Taiwanese companies set up in Mexico, paying slave wages to the workers. And the same day that the story was published Al Jazeera America went out of business. It was one of the few media outlets that would look at a story that was a bit different.

Americans prefer to think that everything is okay in Mexico, the country is reforming, opening up, active on the oil market, has a good record on human rights, when in reality the situation is exactly the opposite. Acapulco used to be a major tourist area, there used to be lots of people coming from the United States with their families for vacation, US students coming for their spring break, but now it has gone to hell and hardly anybody goes there. And even publishing stories about it is extremely difficult.

I doubt that my work can change anything. I only hope to put a new narrative in front of people so they would more clearly see what the situation is, especially in Mexico.

Uncolored and public

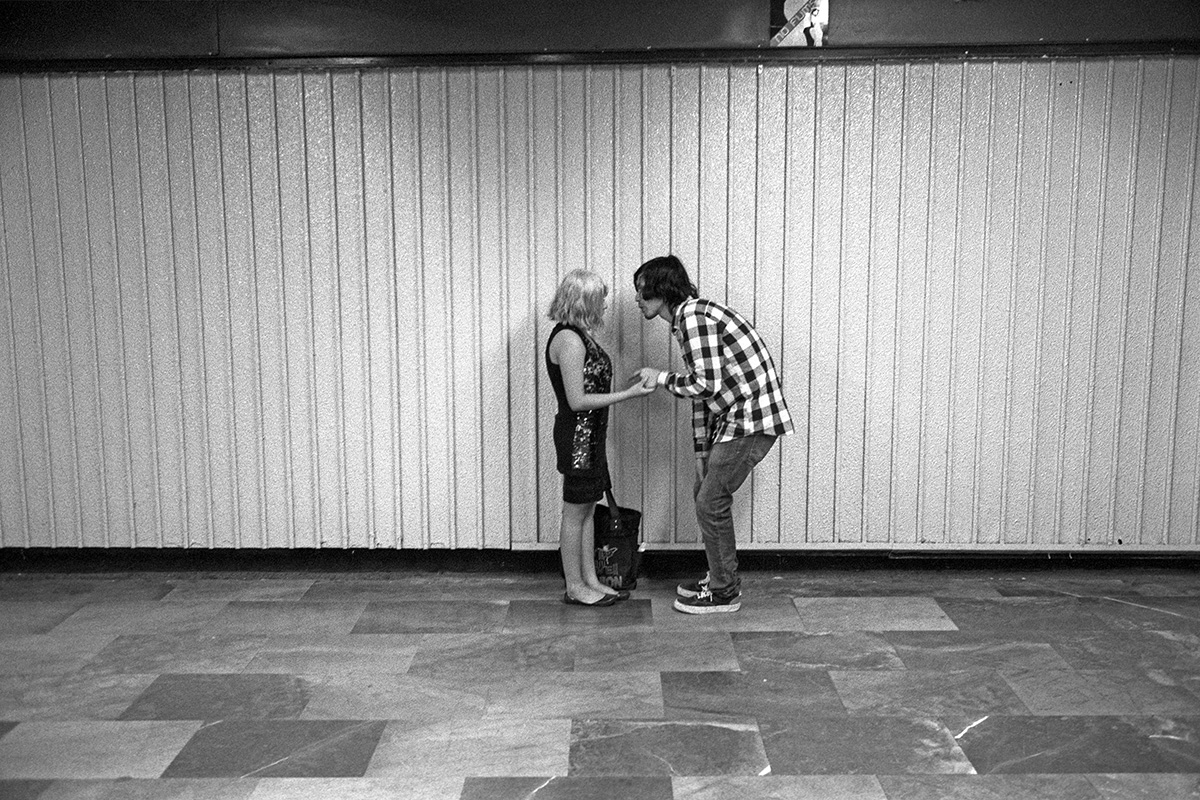

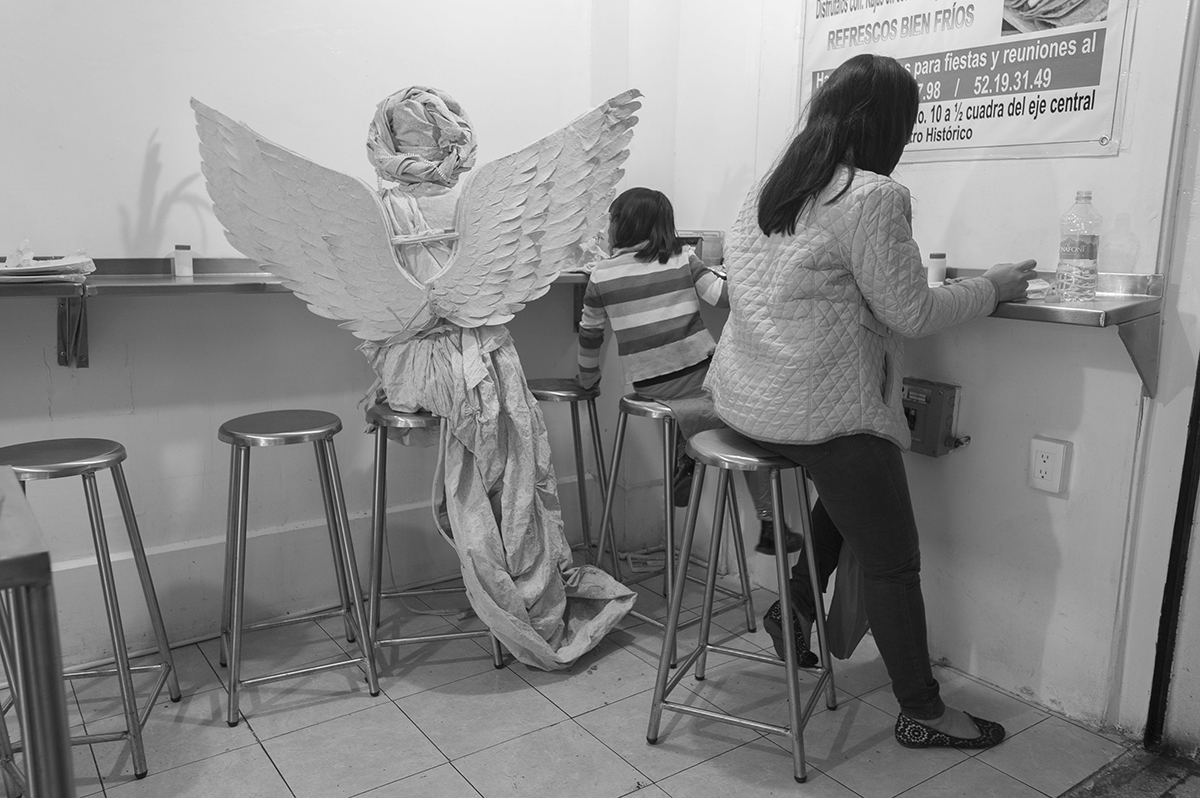

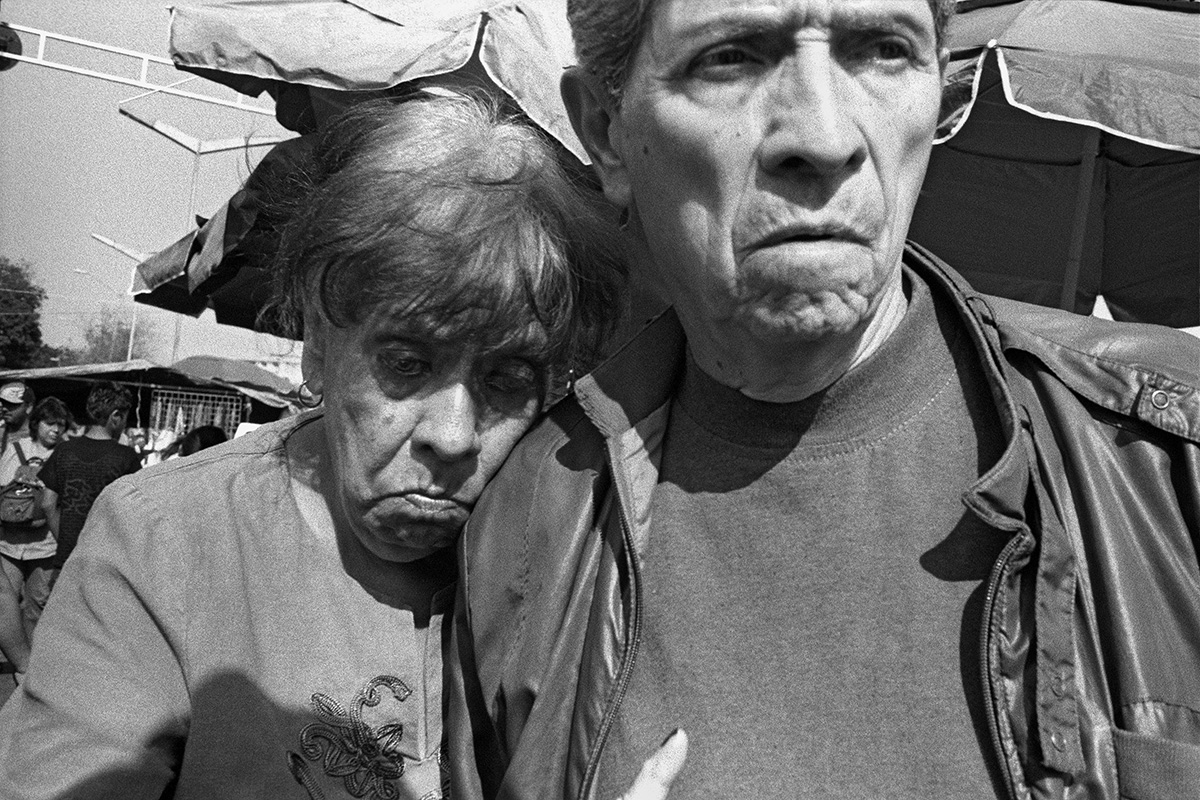

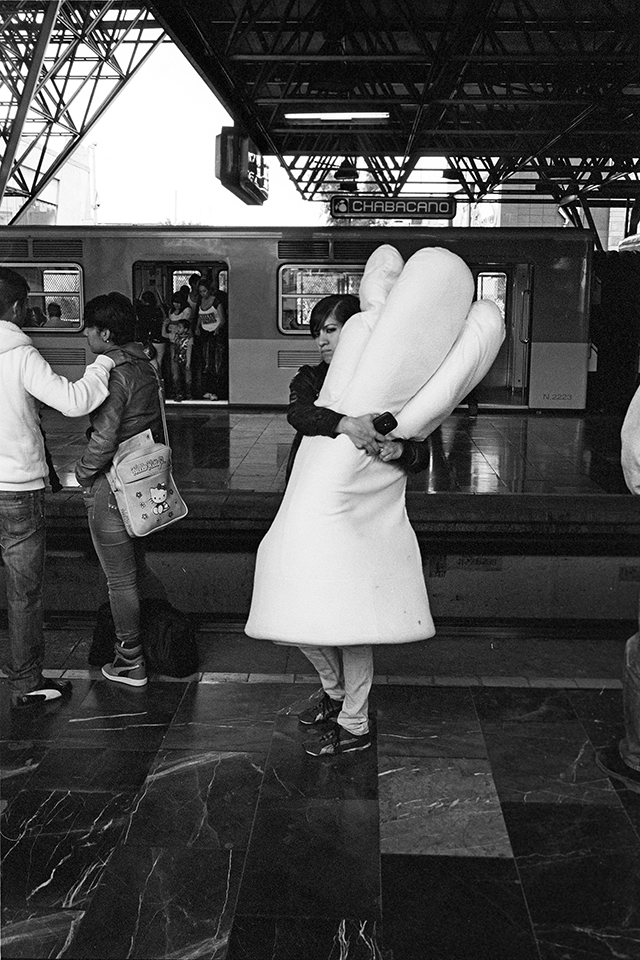

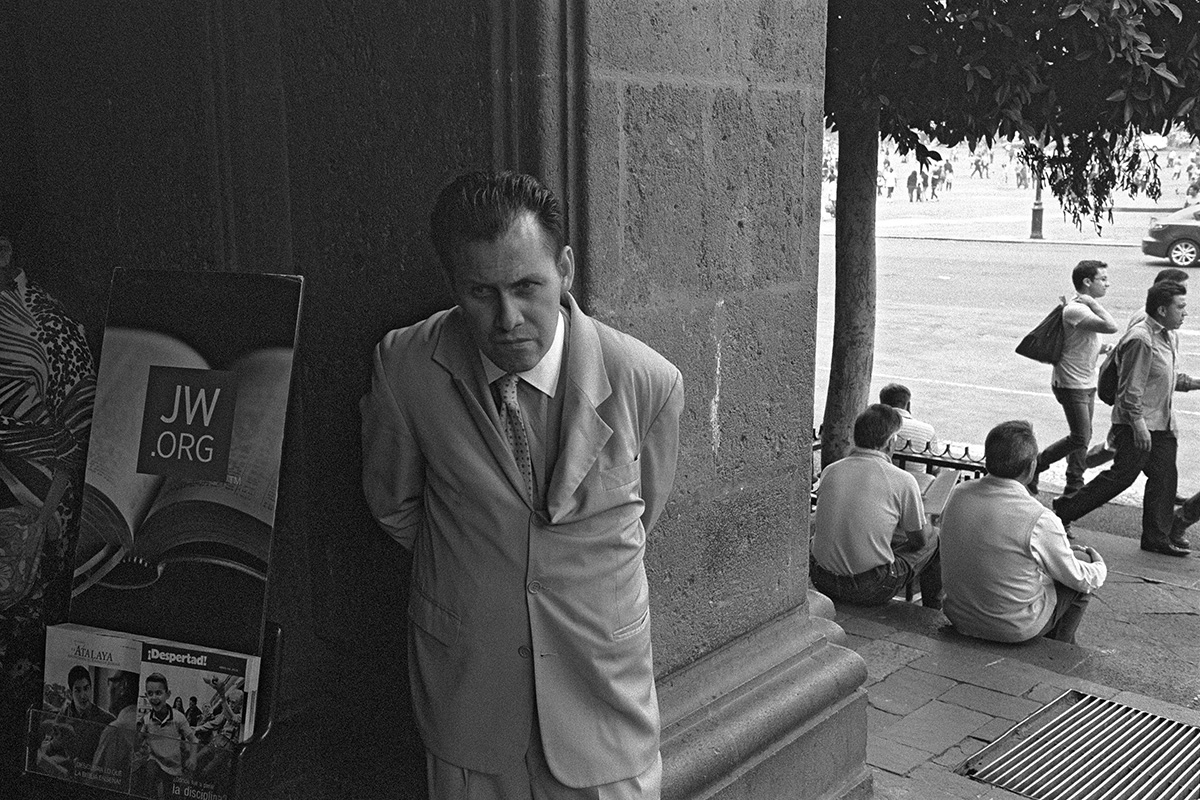

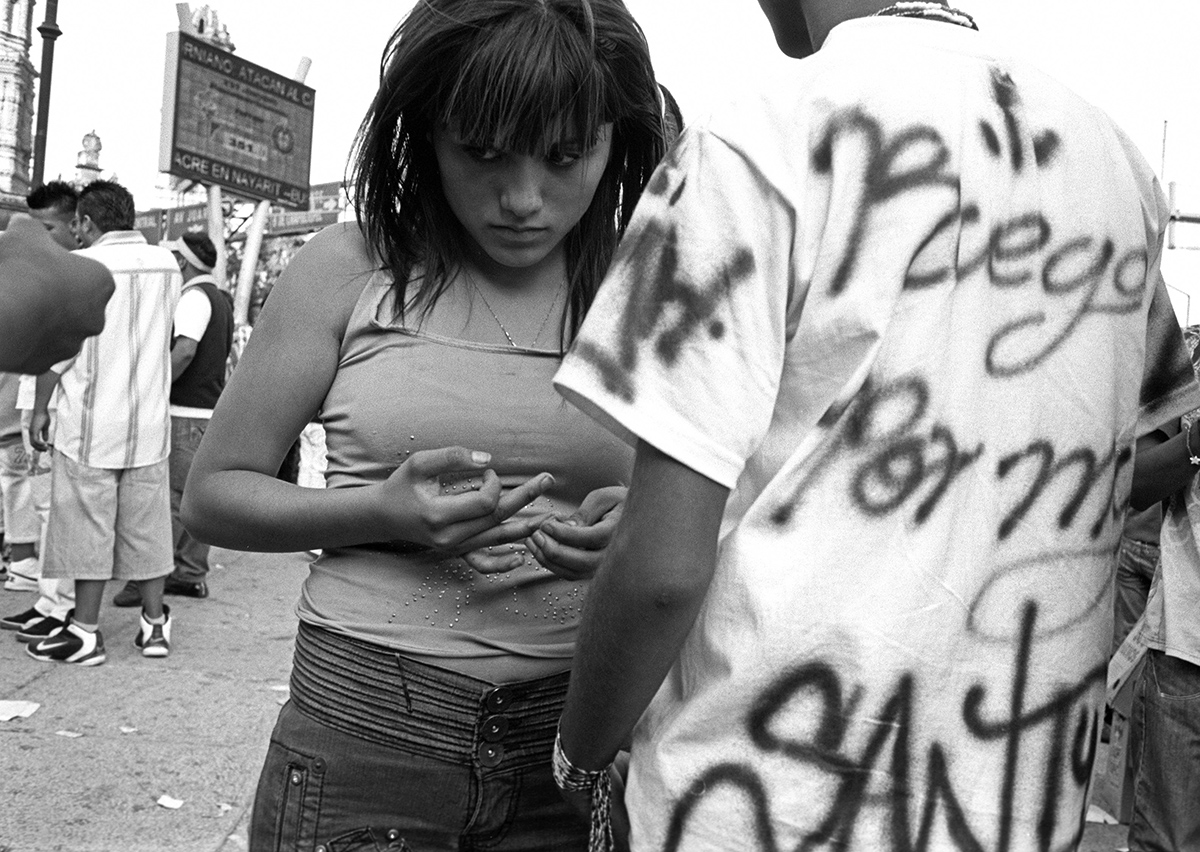

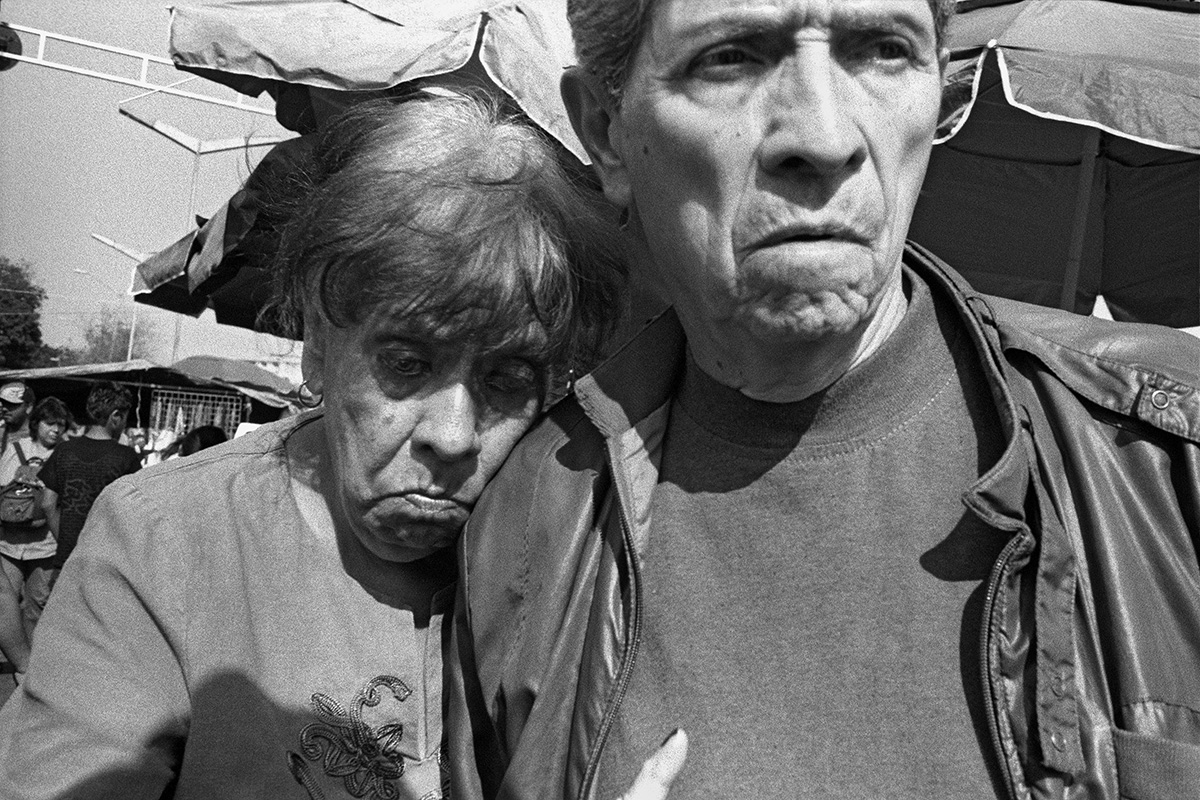

I live in Mexico City. In the morning, you sit in public transportation next to somebody and you say “good morning”. People here still seem to have a certain reverence for life and living. Lots of private things, intimate things people are doing in public spaces. A woman sitting down on the street putting on her makeup while fifty other people walk by; people on the metro kissing, hugging, arguing. And there is no other place to do it because you have to relate to the person in the space that you’re given, in Mexico space is rather reduced, you can’t go out in your backyard — you have to do it in public.

Callegrafia is about that, the name of the project is a play on Spanish words and suggests “what the streets write”: I’m led by the streets, I rely on what’s happening there to be my raw material, my muse, and my resource.

Mexico City is black and white to me. I don’t see much color, especially in the historic center of the city, rather — nude, red with volcanic rock tint, lots of gray. Color adds another level of emotions that I’m just not looking for.

For street photography, I like using a Leica for its quietness, for its size and how it allows me to get closer to people on the street.

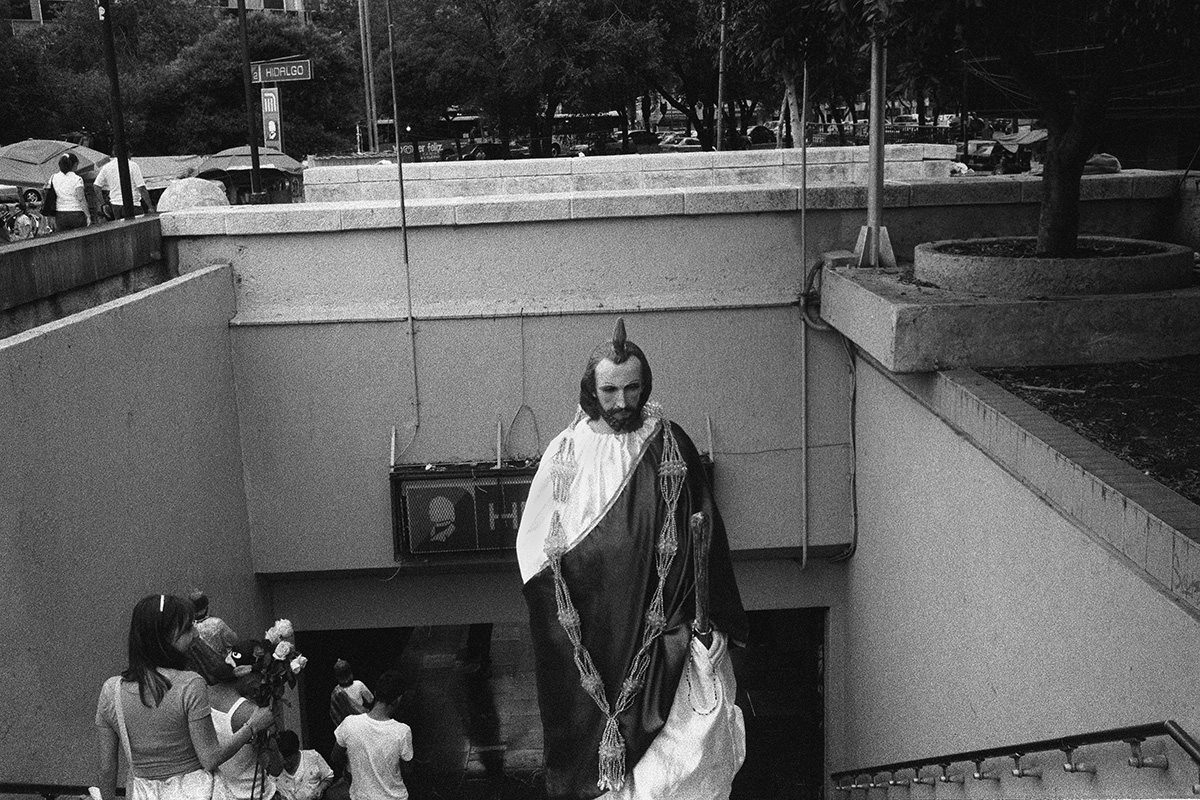

Of Lost Causes

All this takes place in one church in Mexico City on the 28th of every month. Mexicans have different reasons to go there but most of those people are the forgotten ones, they don’t have resources for health care, for good living conditions. They live with a sense of constant insecurity, so they are praying to Saint Judas, who is known as the saint of lost causes.

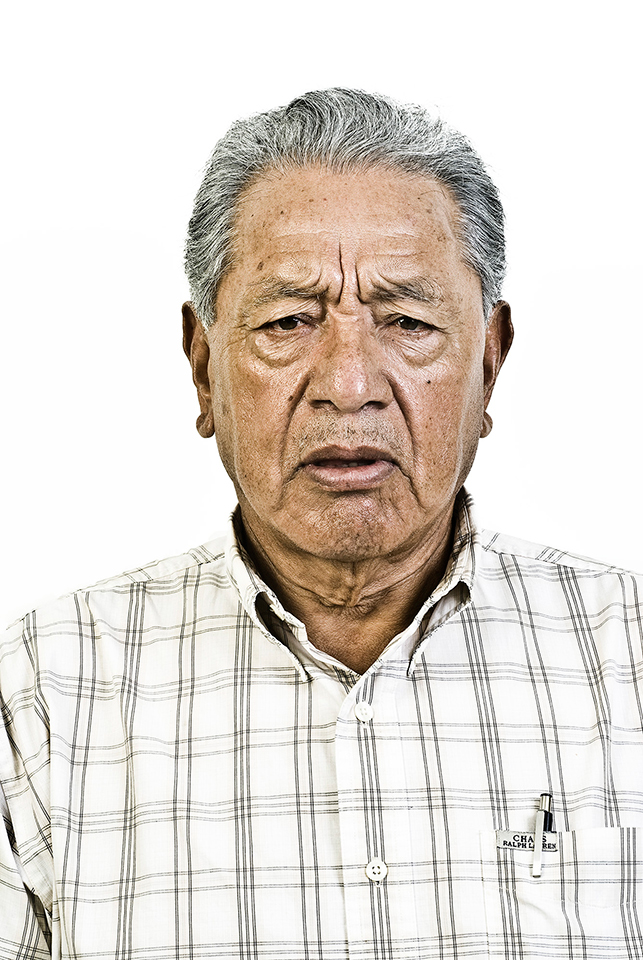

Pepenadores

Bordo Poniente is one of the largest open-air garbage dumps in Latin America, located on the eastern side of Mexico City. There was talk within the city government about closing it down, but people who work there, recycle things and separate garbage could lose their jobs so they started blockades, which created a problem in the city. I got permission from the head of the union to talk with workers, film their work, and take photos of the workers and activists. To show their faces and clothes, reportage shooting didn’t fit, so I did a series of portraits just outside the office, in the little meeting room: white background, two lights, nothing fancy.

La Bestia

Most of these photos were taken in 6-7 hours in one day, I was just lucky to make them: the migrants’ train, La Bestia, doesn’t leave on schedule. You wait hours, even days, and when the train starts moving, people run out and get on it. That day it was 37-39 degrees and some people were staying on top of the train to reserve a place; they stayed on this stove for more than 10 hours.

The train itself is a story. It doesn’t exist anymore as a means of transportation for the migrants: the US government makes the Mexican government stop these migrations through their borders. Now people walk or try getting on buses. I think most people from Central America today I would classify as refugees, not migrants, because they were forced to flee from their countries because of violence, persecution, war or discrimination.

New and best