Life after Chernobyl: Who Still Lives in the Areas Contaminated after the Nuclear Accident

Documentary photographer and photojournalist from Spain. After a career in finance she moved to London in 2001 where she studied Photojournalism at the London College of Communication. Published her work in The Guardian, Sunday Times, Thomson Reuter Foundation, El País, and The Internationale.

— Could you tell us why you decided to take on this project?

— I was interested in Chernobyl for a long time. In 2015, I traveled to Ukraine for the first time to find out the long-lasting implications of the accident for both the environment and the people 30 years after the disaster.

— What is the aim of your project?

— The Chernobyl accident seems to have been forgotten by society. I wanted to give voice to the lives of those carrying on with the poisonous legacy of Chernobyl. With my collective, Food of War, I also created a European exhibition collaborating with artists who were reflecting on the consumption of food produced in countries where the radiation traveled after the accident.

— The world has already seen a lot of projects from Chernobyl. What is special about yours?

— For my project I did lots of research interviewing doctors, liquidators, and NGOs working with the victims of Chernobyl. I became very interested in remote villages, where people have limited access to hospitals and doctors. Life after Chernobyl is a very personal project that portrays life in the Narodichi region, 50 kilometers southwest of the nuclear plant. This turned out to be one of the worst-hit areas by radiation but only detected five years later.

Natalia, the school’s teacher, stands by the entrance of Maksimovichy village, where many houses were abandoned after the Chernobyl disaster. What was previously a prosperous area has become one of the poorest regions in Ukraine.

Iana Vasilieva, a 6 years old at home in Maksimovichy village. Her father committed suicide a year ago.

Tatiana Ignatiuk in her kitchen in Maksimovichy, where she lives with her three children and husband who works in the forest. People are still farming and eating home grown produce.

— You must have seen a lot of awful things there. What was the most shocking?

— I was shocked by the poverty and isolation of these areas highly affected by radiation alongside with the collapse of collective farming due to the fall of the Soviet Union. The authorities are not ensuring a safe environment. There are no nuclear warning signs and people are still farming, fishing, and eating produce from their land that has led to birth defects and infant mortality.

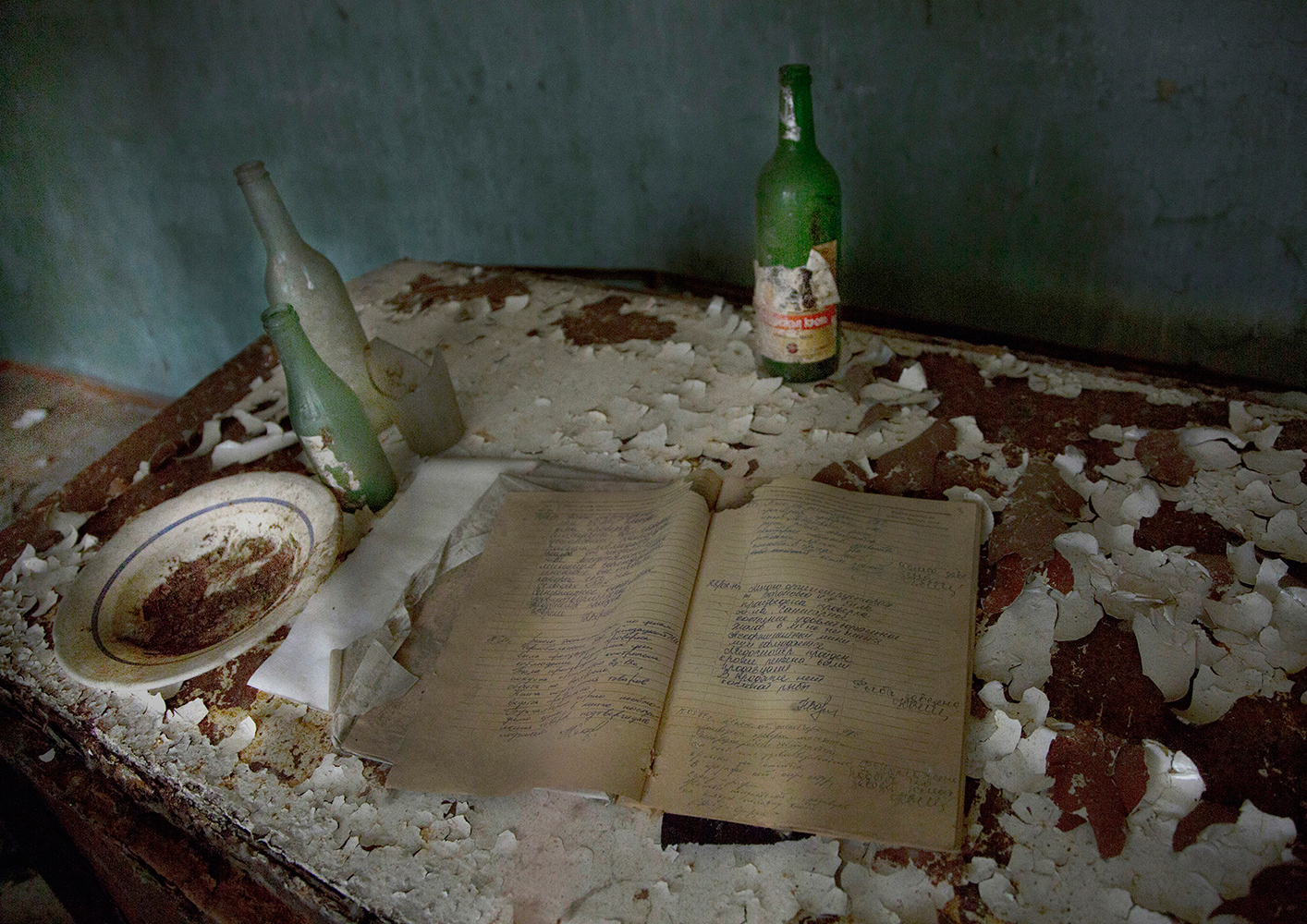

An abandoned house in Pripyat, Chernobyl

A woman is selling mushrooms on the road from Ivankov to Chernobyl. Thousands of people are still highly exposed to radiation and local people consume homegrown produce.

— How long have you been with all those people?

— I traveled to Ukraine four times between 2015 and 2016. I spent four months documenting the situation of Chernobyl, with a total of three weeks with the families from the Narodichi district.

— Did you make friends with any of them?

— I became a very good friend with Nicholas Levkousky who was in charge of the evacuation of three cities in the 1986. He introduced me to the area and its people and from him I learned a lot about Chernobyl. Also, I became friends with Natalia Lukanina, a school teacher who introduced me to many of the families I worked with.

— Which story is the most difficult?

— The harder story I hear was from Emir Natsik and his family. He fled the conflict in Abkhazia (Georgia) when he was eleven, three years after the Chernobyl accident. He moved to live with his grandmother in Khristinovka, 60 km from the nuclear plant. She believed the town was not affected by radiation. Today, Khristinovka is considered one of the towns most affected by radiation. Emir lives with his wife Nastia and three daughters. Lia, two years old suffers from a brain tumor. Emir decided to stay because they don’t have any other place to go to.

— Could they be happy?

— Not really. The parents know they are exposing their children to radiation but they don’t have any other place to go and they complain the government is not helping them. Newborn children do not receive any help as victims of Chernobyl even though it is clear that their illnesses are from the effect of radiation.

Chernobyl’s church in the 30km exclusion zone.

Anna is holding apples from her tree. She lives in Copachi, a village in the 30 km exclusion zone of Chernobyl.

Dentists from Kyiv are visiting Narodichi district villages to check in children’s health. After the Chernobyl disaster many children suffer from malnutrition and illnesses.

Mischa, 4 years old. 30 years after the Chernobyl disaster thousands of people are still living on contaminated land. This has led to birth malformations, weak immunological system effects and various types of cancer.