The Light in the Window Across the Street

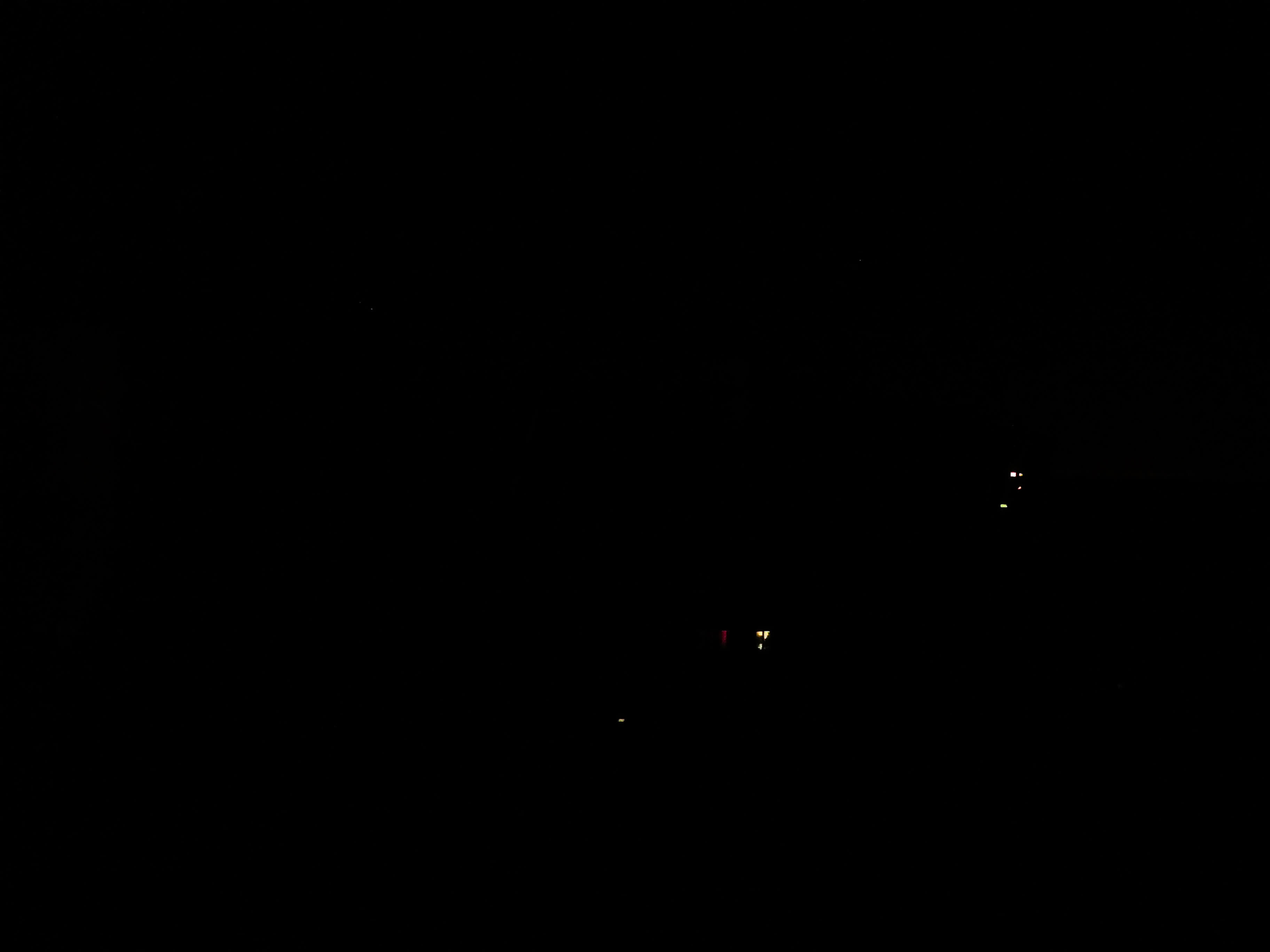

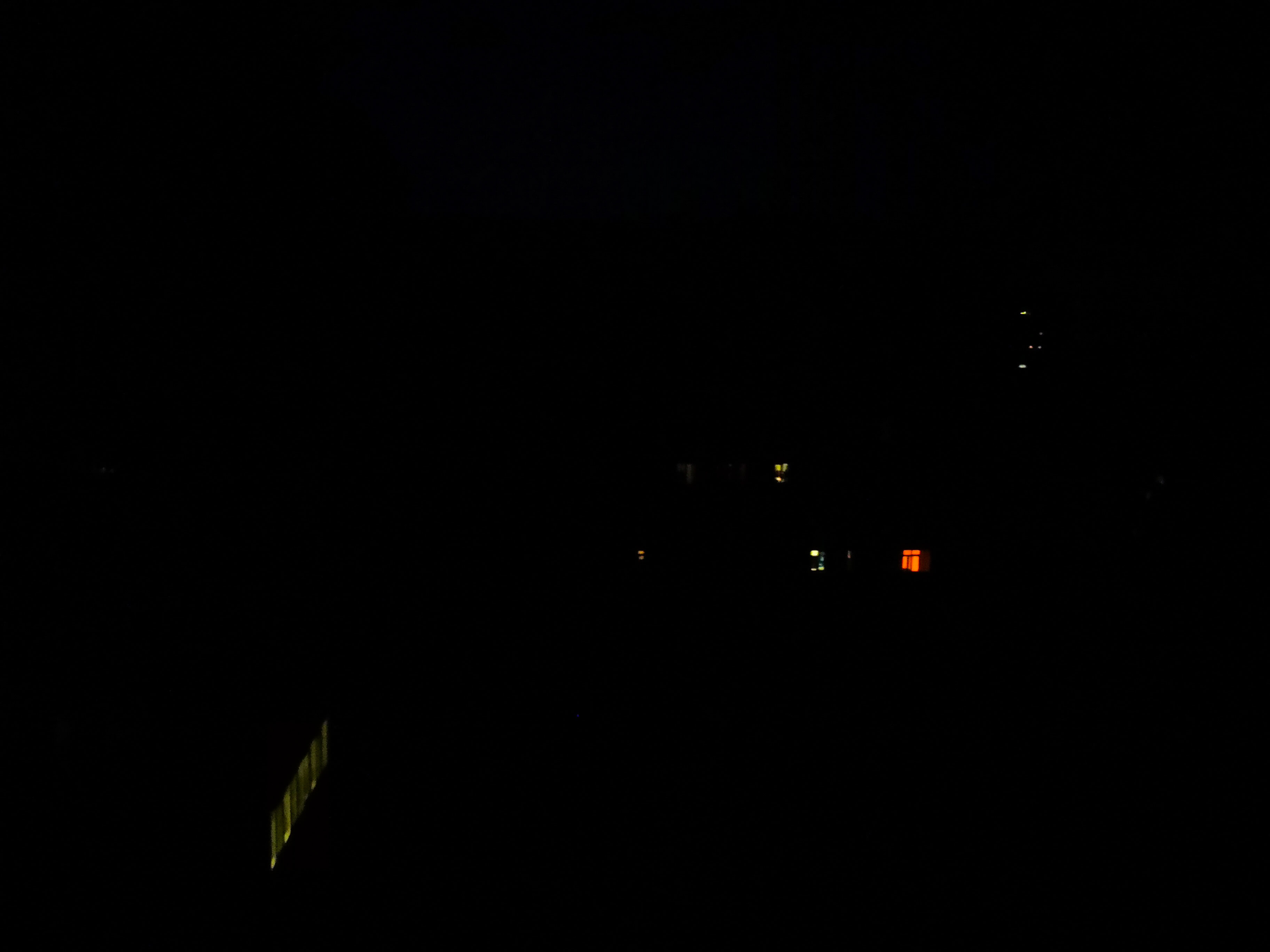

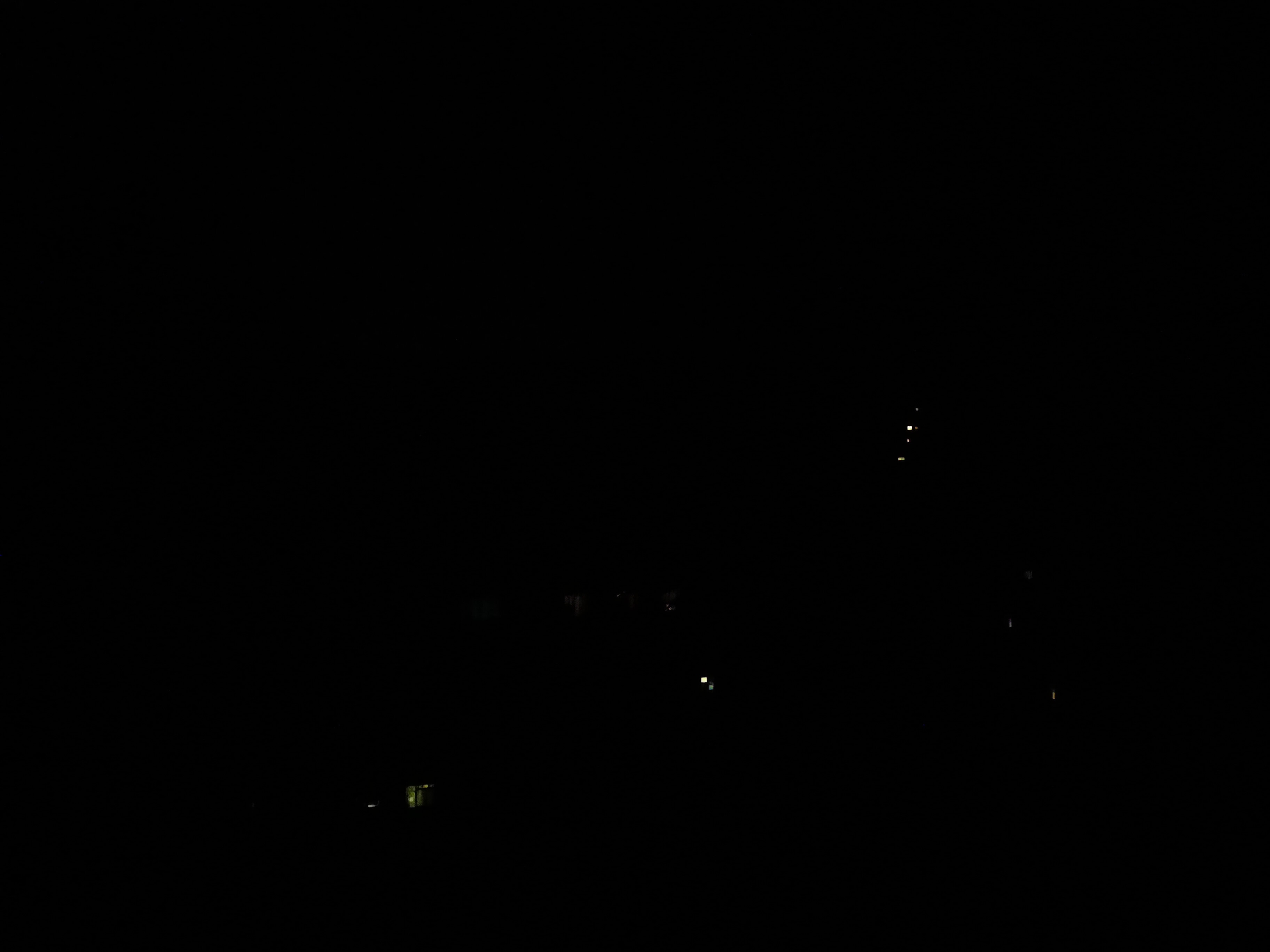

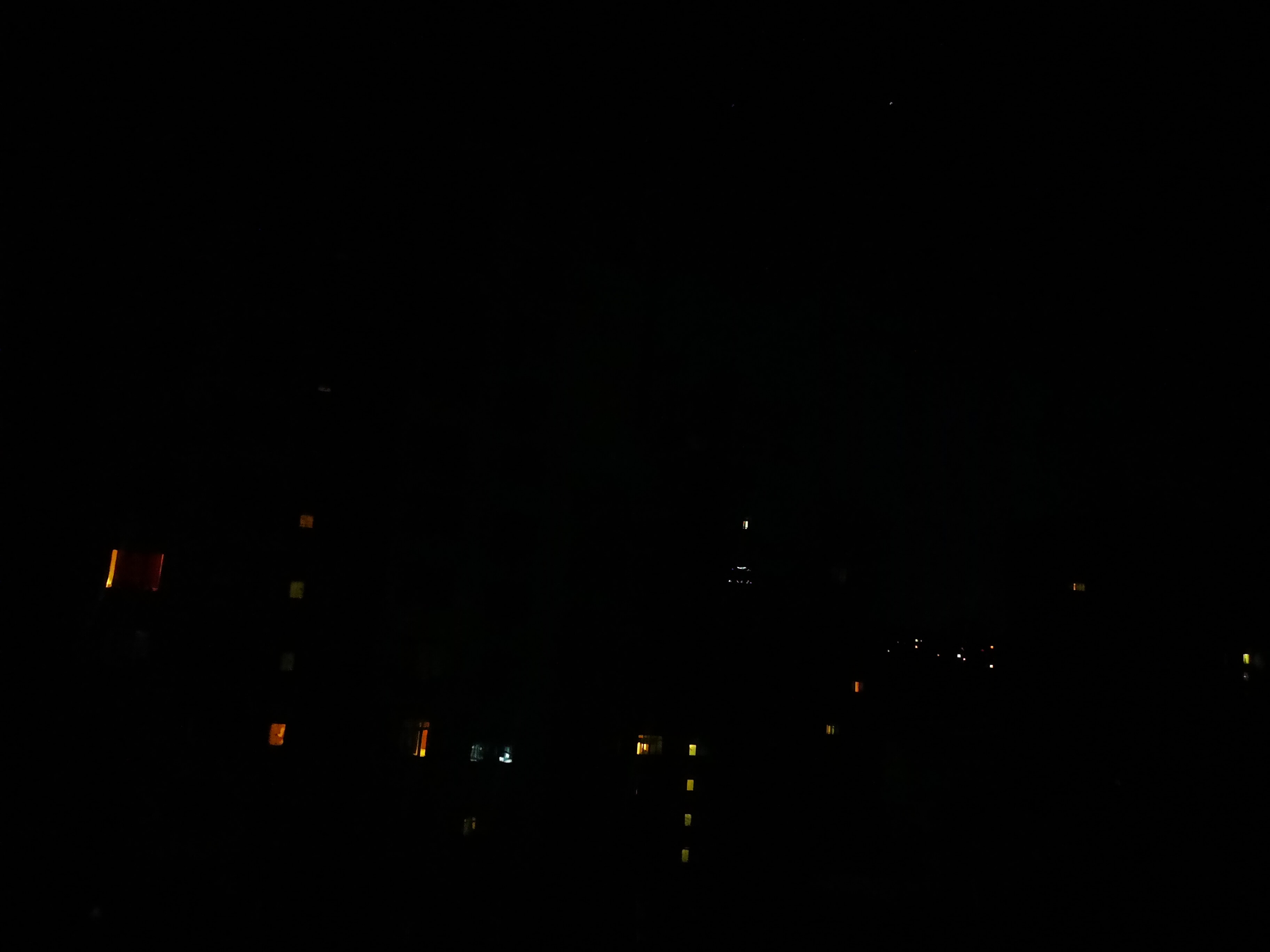

From the first day of the war, Kharkiv suffers under the attacks of Russian aviation and artillery. The rough estimate suggests that more than a thousand residential buildings were destroyed during this time. A lot of citizens were forced to flee their houses, but some of them chose to stay. Among them is Victoria Likholiot, a photographer and author of the “In the dark” series. On the ninth day of the war, she started taking photos of her window view. She captures the decreasing number of lit-up windows across the street. Watching the changes around her and looking for evidence of human presence, Victoria describes her experience of living through the war.

An artist from Kharkiv. Studied at Chekchkov Photo Academy in Kharkiv and Victoria Burlaka Modern Art School in Kyiv. Took part in many Ukrainian group exhibitions.

— I was planning to visit the Anna Melnikova exhibition on February 24. The evening before, I was thinking about what to wear. I fell asleep having these pleasant thoughts and overslept the beginning of the war. I woke up at 9 a.m. and saw a lot of missed calls and messages which said that the war has started. At the same moment, I heard the explosions. But my first conscious thought was about the exhibition: was it still on? A couple of hours later, I knew that it wasn’t.

At first, I was shocked by this new reality, and I had no plans to evacuate. Moreover, there was hardly any place for me to go. Then I counted what “me” stands for. It turned out that “me” consists of myself, my partner, his mom, my mom, and my grandma. The latest couldn’t even walk on her own. I understood that all of us couldn’t leave the city together.

My grandma died on March 19, and only 9 days later, on March 28, we were able to bury her. Before that, on February 25, my cousin died under shelling.

My grandma died on March 19, and only 9 days later, on March 28, we were able to bury her. Before that, on February 25, my cousin died under shelling.

I concentrate on that collective “me” these days. I call my mom, who lives in the Kharkiv center, and text my friends daily. I haven’t been to the bomb shelter yet. We still have food, water, electricity, and an Internet connection. One day, I found puff pastry in the fridge and made croissants. Cooking makes me calmer, and having fresh croissants for breakfast is a small pleasure that we can indulge ourselves in.

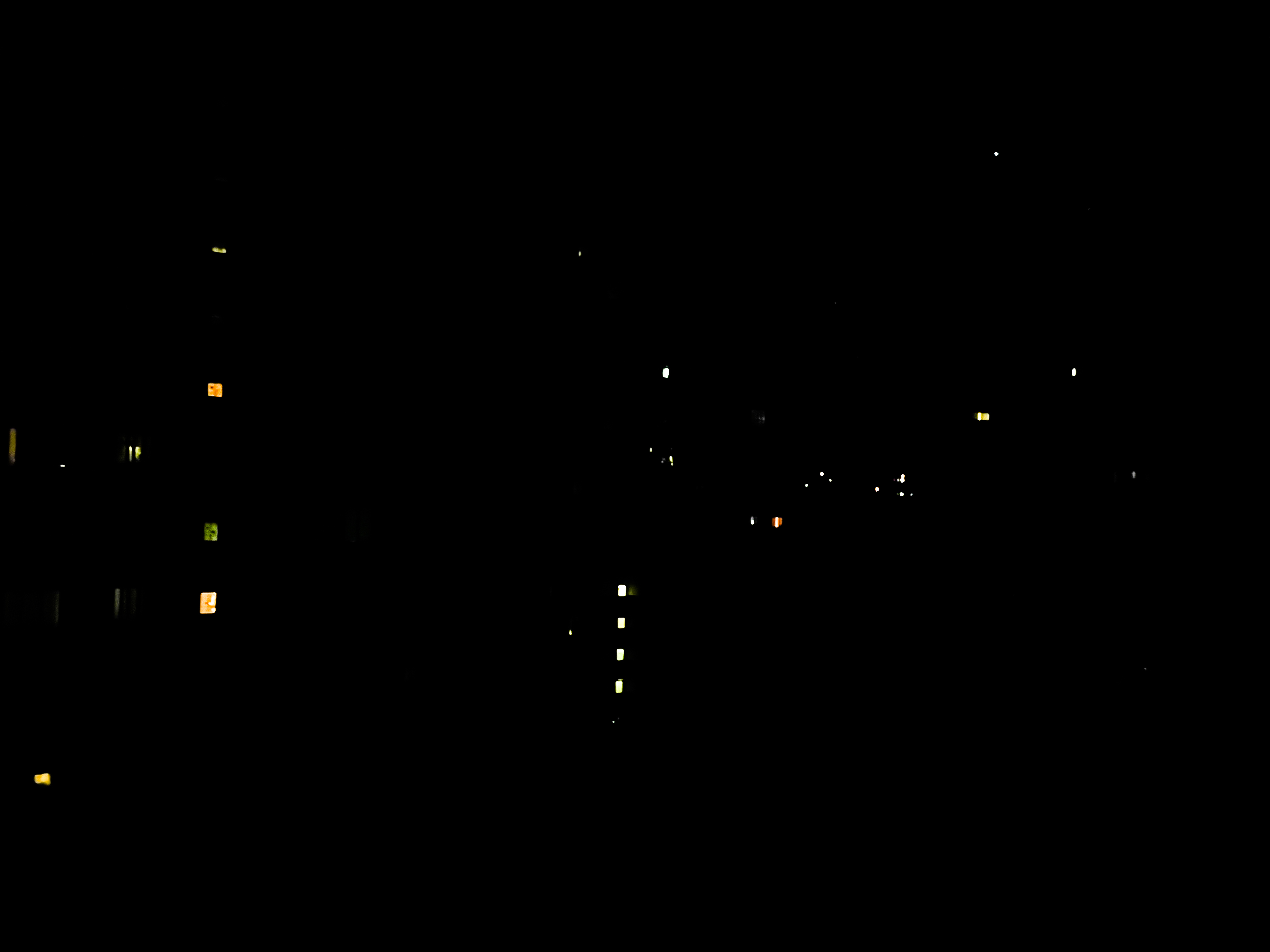

On March 4, I started documenting everything I saw from my apartment’s windows. Before that, I did nothing. On the first days of the war, with a massive military blackout, I had a feeling that we were the only ones who stayed in the city. It was a terrifying and unsettling feeling. But then I saw dimly lit windows across the street, and they gave me hope.

A lot of people have left Kharkiv. But those who stayed started to pull themselves together. At first, people used to spend nights in basements, some of them — on staircases. My neighbors from the second floor nested on a staircase with mattresses, pillows, and comedy movies. Now “staircase beds” are all gone — some people fled the city; the rest got tired of being afraid and went back home. But they are still cautious about turning the lights on. Yet, you can now see young people having small walks or moms playing with their kids on playgrounds—with the unchanging sound of shelling in the distance.

The war is blinding and disorienting. Your whole world narrows down to your apartment. Unlike the pandemic times, you can’t even look out of the window because it’s dangerous. You are right in the thick of the action, but you have only two sources of information — the Internet (if it’s not cut off) and your senses (especially, your ears). You become all ears when you hear explosions. When several airplanes flew above our house, followed by a couple of powerful bangs, I learned a lot of new things about my body’s reactions.

One of the characters in Joanna Chmielewska’s detective stories used to say: “The best way to support yourself is to support others”. A sense of humor helps a lot, especially if it’s dark enough. Sometimes I wonder how ugly am I going to look if a missile hits my house.

This project is my diary. On one hand, I share my experience, including my bodily changes. Sometimes my hands tremble so badly that I can’t focus my camera. It’s a story of my fears, hopes, and fantasies. On the other hand, it’s my way to say that I’m alive and okay.

Sometimes I wonder how ugly am I going to look if a missile hits my house.

I know for sure how this project will end. It’s going to be a photo of brightly lit windows across the street. When the war is over, I’m going to turn on the lights in every room! I don’t know what this day is going to be like. I just hope that it will come soon. And I will get back to choosing an outfit for Anna Melnikova’s exhibition.

March 4

March 5

March 6

March 7

March 8

March 9

March 10

March 11

March 12

March 13

March 14

March 15

March 15

March 16

March 17

March 18

March 19

March 20

March 21

March 22

March 23

March 24

March 25

March 26

March 27

New and best