The Questions of Bauhaus: How to Bring Craft Back to People

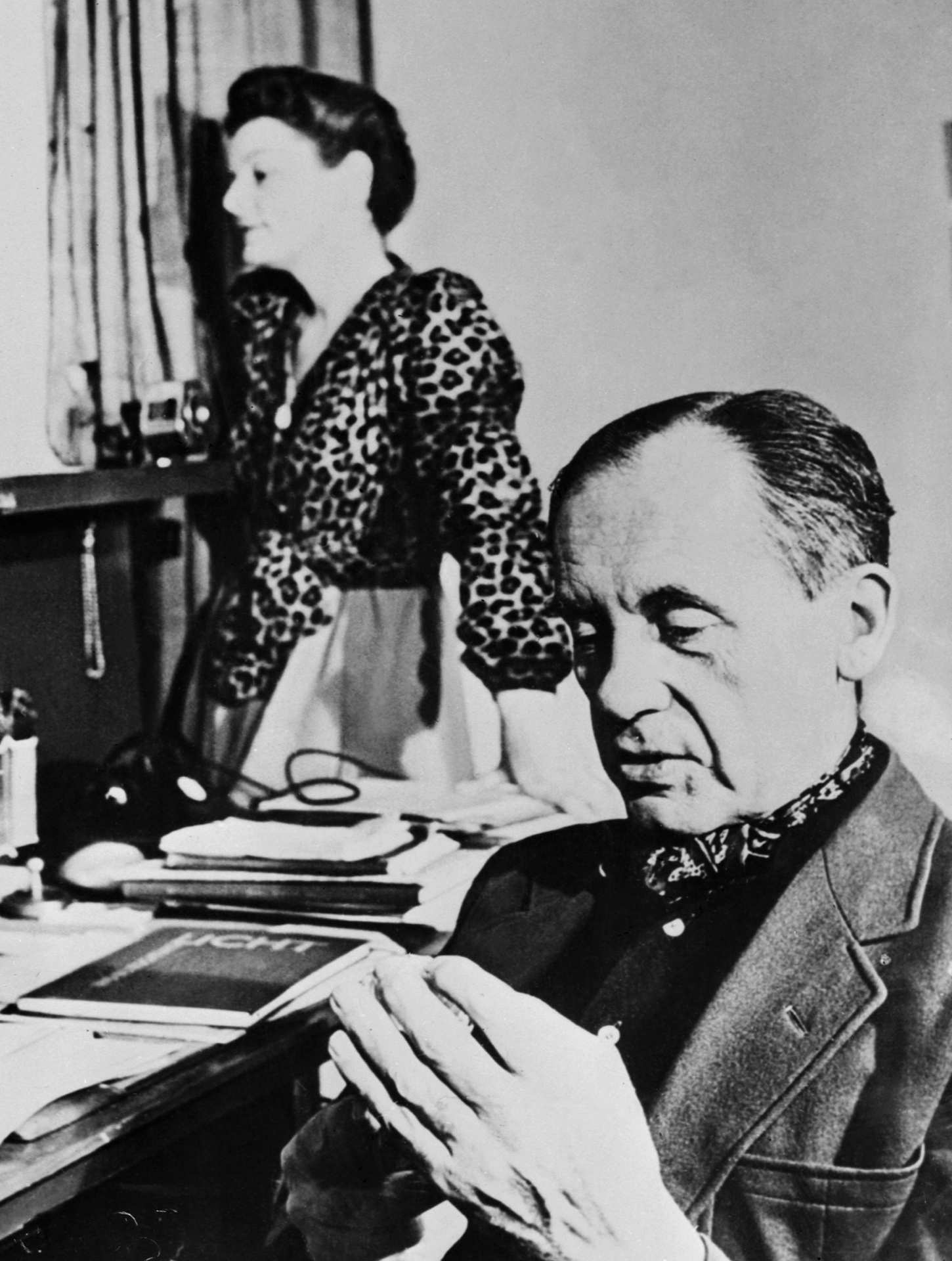

Bauhaus was a school of building and art design that worked in Germany between 1919 and 1933. The art group that formed at the school has the same name, as does the type of architecture. The school was headed by Walter Gropius (in the picture).

Industrial manufacturing that became widespread in the 19th century decreased the role of humans in making things, and later in the construction of buildings. Before, you could more or less exactly say who was responsible for what had been done; with the introduction of machines, it became less apparent. Industrial machines removed many limitations for our civilization, but it is coarser than the hand of a craftsman and lacks aesthetic feeling.

One of the most important items in the Bauhaus School manifesto that was written one hundred years ago is the intention to go back to the idea of craft workshops. According to Gropius and his followers, it is impossible to teach art, but art is the highest point of a craftsman’s work. Only now, the craftsman needs to create, not a unique object, but a prototype that could be reproduced at factories.

The founders of Bauhaus were not the first to have this idea: the pioneer of industrial design William Morris died over twenty years before the school started working in Dessau. Peter Behrens, one of the teachers of Gropius himself, worked for AEG, and among other things, developed design for things produced by the factory: for instance, an electric kettle. However, at Bauhaus they had a better understanding compared to their predecessors of social and economic significance of industrial design. At the school, they dreamed, first of all, to change the world with the help of it (by filling the homes of people of more modest means with good designer things), and then, to get rich.

They wanted to change the world by filling the homes of people of more modest means with good designer things.

Electric kettle designed by Peter Behrens, 1909. Photo: 2019 Peter Behrens / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany

However, none of the intentions were fully fulfilled. The things that were designed in Bauhaus, although they were made mass-scale, were not cheap even for the middle-class of the time. At the same time, the school didn’t bring a sizeable income. However, what happened in the following decades showed that on a global level, their guess was correct.

The owner of IKEA — mass producer of home furniture and accessories, prototypes for which are developed by designers not deprived of artistic ambition — for some time used to be the richest person in the world. Some inexpensive chairs and stools were sold in hundreds of thousands all over the world, indeed changing it. The only area where mass-production of designer things has not yet become widespread is architecture, where we still have a rather strict distinction between a unique author’s creation and something that could be called mass consumer goods. At the same time, typical houses based on design by architects were built both in the USSR and the countries of Eastern Bloc; and today, despite well-deserved criticism, universal solutions remain one of the most obvious possibilities for improving the quality of cheap housing.

We could also say that often even in something that hasn’t been touched by the hand of a designer or an architect, a reflection of well-known samples of design can still be seen. A knowing eye will have no trouble noticing the connections between the modern panel houses that seem faceless and the experiments of great modernists in the 1920s, Chinese one-dollar factory bits and a work by a famous designer.

A chair — part of the exposition dedicated to Bauhaus, Berlin, 2009. Photo: David Gannon / AFP / East News

Philipp Oswalt, director of Bauhaus museum in Dessau, near the Kandem table lamp designed by Marianne Brandt and Hin Bredendick, Dessau, 2009. Photo: Peter Endig / DPA / AFP / East News

We should hardly consider this an undeniable delayed victory of Gropius’ plan. Firstly, many were not happy about the penetration of functional design, not to mention architecture — to the extent that Walter Gropius is often seen to be almost as sinister as Le Corbusier. The world has learned the lessons of utility and repeatability from Bauhaus very well, missing other, prettier ones.

Secondly — and more importantly — the everyday impact turned out to be not quite predictable. The cheapness of chairs, t-shirts, cocktail straws, and cups had a colossal side effect of losing value of all things in general. The world is flooded with everyday garbage that consumers obtain with very little effort. We can’t say that the new craftsman is responsible for this, but he is also not able to control what is going on. And what it worse — he cannot always predict the impact of what he made with his own hands.

The cheapness of chairs, t-shirts, and cocktail straws,and cups had a colossal side effect of losing value of all things in general.

In fact, the craftsman managed to penetrate the production, but the ethical dilemma that this penetration was supposed to remove remains unsolved — and only more obvious. The very existence of over six hundred pages of Richard Sennett’s book The Craftsman proves how undefined is the role of the craftsman or, simply speaking, a professional in the high tech world. Sennett has an important idea that craftsmanship has its own ethics, is a source of motivation different from the market one — the one where skill is self-sufficient.

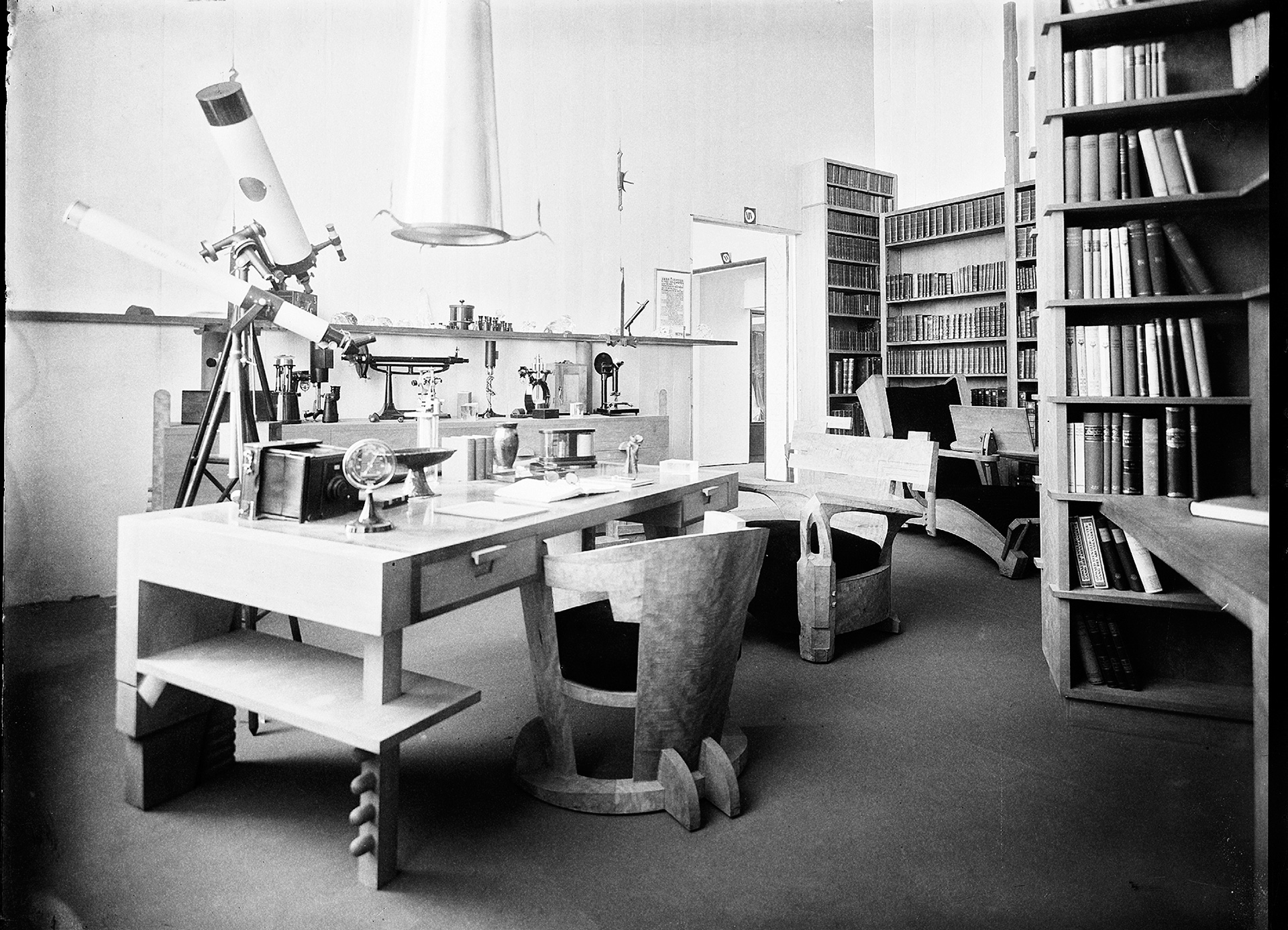

Student’s workplace, concept by Peter Behrens, 1923. Photo: Austrian National Library / APA-PictureDesk / AFP / East News

Medieval guilds could not only teach craft — using a certain position in society, they could control the quality of products, at least in the region where they were located. Modern professional communities can be good in the former as much as they want, but the latter still remains a problem. At Bauhaus, they tried to one-sidedly return the status quo: by letting the craftsman go outside the workshop and spread his influence beyond the things that he directly creates. And over a hundred years became rather inventive in this — started making building sets that allowed for the creation of different objects from the same components, learned to involve regular people in its work, and use mass media for its benefit. Digital technologies will soon allow the craftsman to become omnipresent, to solve any tasks in any place on Earth. However, even today, when we see ugly buildings and chairs that are uncomfortable or built from ‘bad’ materials, the reason is hardly the lack of wit of a craftsman who did not manage to adapt his skills to the needs of billions of people, politicians, and incessantly growing economy.

The successful reunion that Gropius dreamed of is impossible without the society also taking a step towards the workshop, acknowledging its values as necessary, even if not entirely understandable. At the same time, something like this could hardly happen according to anybody’s will, and there will hardly be such a will, so we need to rely on a sobering catastrophe or an inexplicable happy coincidence.

Photo by Walter Gropius: DPA / DPA Picture-Alliance / AFP / East News.

New and best