The Questions of Bauhaus: What, If Not a Building?

The idea of a house as an ultimate result of any creative activity has two aspects. On the one hand, it denies the independent value of non-applied arts, aims to turn back the revolution that happened when a painting was first painted on a separate piece of wood, thus separating it from the wall and letting it roam free.

On the other hand, it also defines the building as the final product, a thing in itself. It was the building that was supposed to house the utopian world of the future. This was another great prophecy of Bauhaus, although its fulfilment can hardly be called a great success.

Bauhaus building in Dessau, Germany, 1930s. Photo: Karl Heinrich Lämmel / United Archives / East News

Urban planning as a school subject, of course, existed, but it was the building that had sacral meaning, like the cathedral in the Middle Ages. It was, however, different from the cathedral because of the utilitarian attitude of its purpose. The same attitude was supposed to dictate the exterior of the buildings — and this where “form follows function” comes from, uttered by Louis Sullivan, the author of the early American skyscrapers. This phrase could mean different things when said by different architects, but it always meant almost a deification of performance.

It was the building that was supposed to house the utopian world of the future.

When following this principle, open urban spaces inevitably lost to buildings. Formally, there were still streets and squares between houses, but in reality, even if they were used for some specific task, such as for traffic or children’s games, they became the glorification of the idea of space that was formed during the Renaissance. In the interiors, a modernist city meant the victory of functionality, and on the outside — the victory of emptiness.

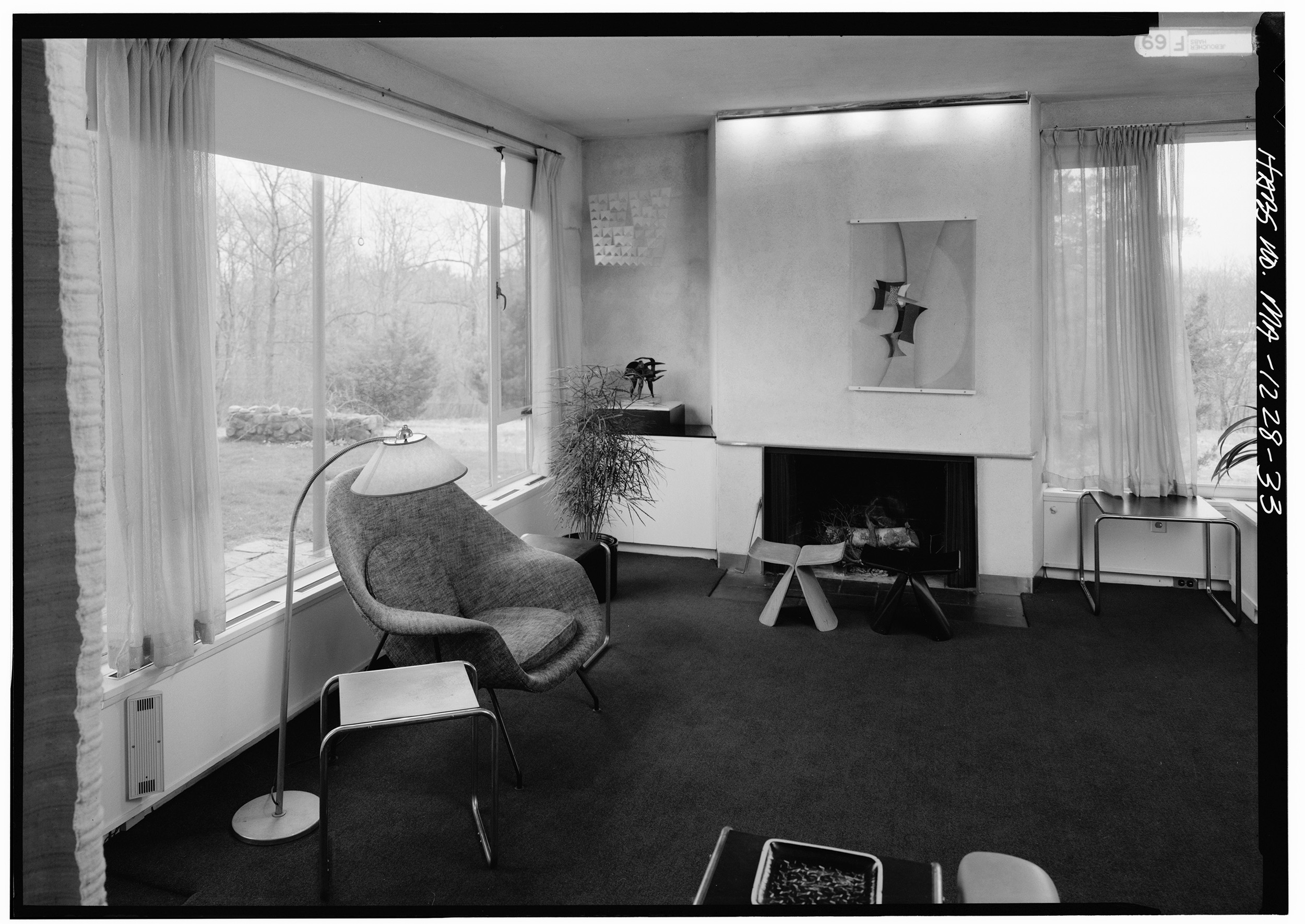

A living room in the house of Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus architecture school, 1938. Photo: Historic American Buildings Survey / Library of Congress

This is where the main urban drama of the industrial epoch stems from: the city in the understanding that was conventional by that time stopped existing. The new architecture of expediency didn’t see any sense neither in narrow Asian streets, nor in a lively Italian piazza or capital parade avenues.

The theoretical works of the 1960s and 1970s were in one way or another dedicated to the problem of the city. The first thing that the architects pointed out was the role of facades as decoration that creates the image of the place. In his Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, Robert Venturi wrote that architecture happens when internal and external forces collide. He said that architecture as a wall between the inner and the outer becomes the spatial documentation of this drama and its resolution. And by acknowledging the difference between what’s inside and outside, architecture once again opens the doors for the urban point of view.

To acknowledge the importance of the wall wasn’t enough. The things that are beyond it also quite naturally fell into the scope of attention. Life Between Buildings by Jan Gehl, who is very famous now, but wasn’t this well known half a century ago, was published in the 1970s and through simple rules explained how to design streets, squares, and yards so that people would spend more time there.

In general, in 20 years so much was convincingly written that this should have exhausted the topic and the cities should have gone to their regular state. However, this still hasn’t happened, except in separate districts of the most prosperous cities of the world.

Dizengoff square in the White City of Tel Aviv, 1940-1946. Photo: Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph Collection / Library of Congress

It is typical that almost all thinkers of the 1960s and 1970s, regardless of their background and worldview, addressed the previous experience, rationalized it, and tried to adapt it to the reality of the 20th century which became the main obstacle. Although the architects once called the building a potential temple, and function — its deity, not they alone were the reason for the new order of things — and they were not in a situation to finally break it.

The world has never lived through such urbanization as it does now, and it is naive to be certain that it is possible to govern it with methods that are a hundred years old or older.

In Bauhaus, they dreamed that a utopian house will appear in the communist world where everyone would be content with the scarce minimum. A real modern house exists in the conditions of the market, even if this market is not always free. The more square meters there are in a building, the more money it brings, the more functions/services it can offer to more people. The modern building — according to the laws of competition — immediately uses any offers for its good and against the city. People lack beautiful facades — so shopping malls grow tiling from artificial stone, a simple-minded reminder of art deco. Professionals note the importance of a variety of functions — and inside one skyscraper we find a shopping mall, an office center, a hotel, and several restaurants with a great view. They say that we need more greenery — and it may immediately turn up somewhere on the staircase of the twentieth floor.

People lack beautiful facades — so shopping malls grow tiling from artificial stone, a simple-minded reminder of art deco.

Parkroyal hotel in Singapore. Photo: Paolo Rosa / Flickr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The triumph of the building that we observe is different from the utopian Bauhaus building in worldview. The source of happiness in it is an almost infinite variety of possibilities — instead of the communist sufficing with the necessary.

There may be different views on the drama of the city being devoured by buildings. From a humanistic point of view, we should suppose that the mind can conquer natural processes and govern them, which means, after some time and effort, bring back the status quo where the building is merely a subordinate element of the urban construction set. From a pragmatic point of view, we would have to admit that buildings can ‘house cities’ and adapt houses to it: distribute infrastructure between the floors, and make it as fully-featured as possible. So, in fact, we would have to assign the same needs to each house that we used to assign to a medium-sized district.

There must be a humble compromise somewhere between the two extremes, but the humanity, being used to implement only its most extreme fantasies, will hardly choose it.

New and best