Manu Brabo: “They Suddenly Called Me and Asked What Have I Done That the Ukrainian Prosecutor Wants to Talk to Me”

Freelance photographer, lives in Spain. Has covered coups and wars in Haiti, Honduras, Kosovo, Libya, Egypt, Syria, and Ukraine. He won the Pulitzer Prize for photography in 2013 for his work in Syria. Published his work in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Al Jazeera, Paris Match, and other media outlets.

The way from the rear to the frontline for me is the most intense time: you know that the enemy is somewhere, but you don’t know where, you know that the shooting is gonna come, but it’s not coming yet.

I basically started as a war photojournalist during the Arab Spring. <...> At that time, I was more of a writer than a photographer. First, I went to Tunisia to cover the refugees, and then I went to Libya. I was kind of lucky, because I had no money at the time — I was with my two cameras and a tiny backpack, and one friend of mine loaned me 300 Euros, and another friend of mine was working for a newspaper, and he got the newspaper to pay for my flight — they probably don’t know about it until now, but they paid my for my trip.

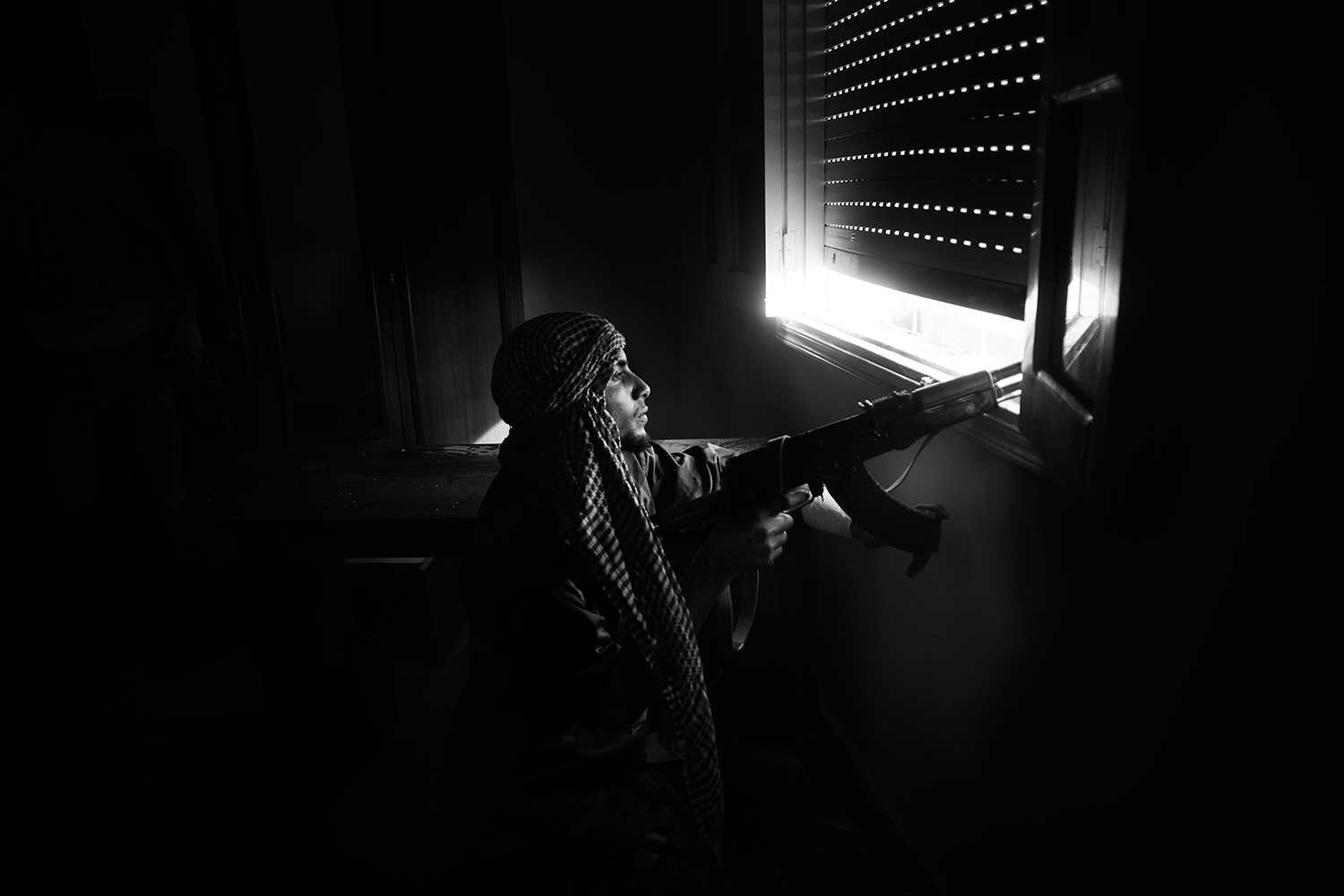

Sirte was the last stronghold of Gaddafi’s forces, the place where Gaddafi was hiding. But I didn’t know it at the time. Nobody did. We thought he was clever and he was somewhere in Africa. I was covering the Battle of Sirte — this was my way of honoring Robert Capa and Eugene Smith, who were my big influences. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do a story like they did in their time.

Libyan rebel soldier shoots his AK-47 against loyalist troops in down town Sirte, Libya, Oct. 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

Libyan rebel soldiers shoot their machine guns towards loyalist troops in Mauritania district in Sirte, Libya, Oct 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

Libyan rebels patrol the Airport searching for enemies after the airport was taken from Loyalist control, Sirte, Libya, October 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

Libyan civilians fleeing from Sirte during the first days of the battle. Near Sirte, Libya, Oct. 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

Before the offensive, the rebels gave the civilians two or three weeks to get out. Sirte was really like a movie scene — almost empty, mostly the fighters and lots of shooting.

One day we arrived, and I realized that the people were smiling a little bit too much. And they told me that the war was over and they had the city. I started shooting some pictures of people celebrating here and there, and then some guy arrived and told me to follow him because they had caught Gaddafi. And I told him, yeah, like two weeks ago, like six months ago… These guys were catching Gaddafi every now and then, so I didn’t believe them. And because I didn’t believe them, I was late 30 minutes for the capture of Gaddafi. Well, for the journalist it’s like this sometimes.

I was captured by Gaddafi’s forces and we spent 45 days in jail. <...> I still have no idea how I was released. I know that in my country my friends were putting pressure on the government, and the government was negotiating with Gaddafi, whose government was still formal at the time. I also know that there was a part of Gaddafi’s family that was led by Saadi, Gaddafi’s son, who wanted to release us. There was another part of the family that wanted to kill us. So, they had their negotiation there. I have to say, it was not that bad, if you compare it with the people who were kidnapped by the Islamic State.

A smoke column rises up from Ouaga Dougou complex during the assault towards the compound. Sirte, Libya. Oct. 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

Libyan rebel soldier takes cover behind an iron door in Ouaga Dougou compound in Sirte, Libya, Oct. 2011. Photo: Manu Brabo

At the beginning (of the conflict in Syria — Ed.), there were very few foreign journalists living in Aleppo proper. And we were really welcome. People expected that the journalists arrive, show the drama to the world, and the international community will help them.

But soon they realized that all the work we were doing was not helping them. The journalists came there, showed the tragedy to the world, got money for this, and the locals got bombed by Assad. So, there was a point when we were not that welcome anymore.

In my last week in Aleppo I was working so to say undercover — long beard, long hair, trousers like a fisherman or a jihadist. And I wasn’t sleeping in Aleppo, I was sleeping in different places every night, many nights I was going to the villages where I knew that the militias in the village were cool with me. But in Aleppo, by that time, there was al-Qaeda and the beginning of Islamic State.

I shoot color a lot, but for the agencies. When I take time for myself, I shoot black-and-white. It looks different when it should be black-and-white, you are interested in some other things, light, of course, but not colors. When I shoot black-and-white I am thinking more about how it makes me feel, rather than how it will make you feel.

When we work for the media, we don’t sell gory photographs. But when I work for myself I take photographs like this, because I want you to see them — this is disgusting, you don’t want to look at it, but this is the sh*t that’s going on there at war.

FSA fighters advance during fighting against Syrian regular troops in the district of Izaa, Aleppo, Syria, September 2012. Photo: Manu Brabo

A house within rebel control area after being targeted by Syrian regular forces. Aleppo, Syria, March 2012. Photo: Manu Brabo

I thinks that Ukraine has some kind of heritage from the USSR-era — people don’t get to understand free journalism yet. Propaganda is all over. The media are always taking sides. If you cross the line and go work on the pro-Russian side, someone would tell you that you are a traitor.

I took a photograph of a funeral of a four-year old boy for the agency. His name was Artem, and he was killed by Ukrainian artillery, and I wrote that in the caption. The picture was strong, and it got bought by the media. And suddenly I get a call from the AP: “What have you done? The prosecutor in Kyiv wants to talk to you.” He wanted me to prove that that boy was killed by Ukrainian artillery. So, when I sent them the Human Rights report, I thought that everything was over, but no, every two days I was receiving calls. But I don’t know how Ukrainian photographers work, because if you publish something that is not the point of view of the government, the prosecutor will talk to you.

During the battle for Debaltsevo I was for three days on the pro-Russian side, and then I was for three days with the Ukrainians. It’s my job, it’s not like I am trying to sabotage the national pride. You read the news to realize what is going on, not what you want to go on.

If you look at all these war pictures, you can see that I am interested in violence as a phenomenon, and how the human beings manage to survive in that kind of environment. And through the images you get to know that there is probably not such a big difference between wars in Iraq and El Salvador, Ukraine and Libya.

Donetsk, Ukraine. Photo: Manu Brabo

3 km from Donetsk Airport in Kievsky district in Donetsk, Ukraine. Thursday, January 22, 2015. Photo: Ap Photo / Manu Brabo

There are cliches in photojournalism. I also have a lot of cliches — I used to be an artist, I have Caravaggio, I have Rafael, Velasquez, and Goya, all influencing me.

PTSD is something you don’t get rid of. You learn how to carry on. From time to time you forget about this, from time to time it is heavy again. The worst thing is not nightmares. It is when you don’t match so well in the society you belong to.

Am I tired of war photography? I think I am addicted to it. I like my job, somehow.