The Cost of Curing Cancer: Sinjar after ISIS

A photojournalist born and based in Bern, Switzerland. Documents conflicts and social issues. In the past few years his work has brought him to places such as Lebanon, the Gaza Strip, Ukraine, Central Asia, China and North Korea. From December 2015 to January 2016 he visited northern Iraq to report from the ISIS frontlines.

I stand in the middle of a moonscape, which by a second look can be identified as the remnants of a town. The cleansing fire of air strikes stripped this place of all life and shape. A new wave of airplanes are incoming now. The target, some structures and its occupants, destined to turn into fire and then dust. Marked and crossed off a list by officers leaning over maps somewhere far away. This reminds me of the concept of looking towards a long dead star, still visible but in reality already gone.

A brief flash, a fast climbing pillar of smoke and with some delay the roaring thunder of the detonation that has me reflexively drop to my knees. From this new angle of vision, I can see a human leg sticking out of the rubble to my right. Torn khaki pants and the still attached black military boot gives it away. After fine tuning my eyes to this anomaly, I can make out more bodies in this grotesque setting people once called home. Some of the corpses are already skeletonized, others badly burned or half rotten. “Let’s move” says Nasir, the Yazidi sheik who agreed to show me ruins of Sinjar and it’s surrounding frontlines.

Our group of five, Sheik Nasir, translator Samad, our driver, a Peshmerga fighter for additional security and me. After a couple of minutes we are greeted by a group of men carrying disarmed Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). These IEDs were carefully placed by the retreating ISIS fighters.

A couple of nights earlier, an approaching ISIS suicide truck was stopped by an airstrike. We reach the spot within a few minutes, passing what used to be a densely populated town. It seems against all odds that anyone could survive this level of destruction. How ISIS fighters managed to do so, I had to find out later.

The detonated suicide truck was brought to a sudden halt in the middle of what used to be a shopping street. Everything non-metal, such as tires, seat fabric or wires were swallowed by the fire that followed the explosion of its deadly cargo. Some of the welded on steel plates, which made the truck immune to small arm fire, lay scattered in the surrounding area. I step up to the cabin and find only the hip bone of the driver remaining.

The ISIS fighters occupying Sinjar must have realized early on that soon they would find themselves lined up in the crosshairs of warplanes. So they brought in workers to dig systems of tunnels, connecting houses and neighborhoods, while remaining invisible to the never resting eyes of drones. Sheik Nasir brings us to one of over 70 so far discovered tunnels. This one has several well hidden entry holes in different buildings on two sides of a street.

Down we crawl into the consuming gloom of the tunnel. My vision, adjusted to the new light, unveils the life conditions below the surface. Stacks of canned food, yogurts, eggs, ammunition, makeshift sleeping corners, plastic fans and several copies of the Quran. They even managed to wire electricity down here. Most of the ground is covered in half-empty or empty painkiller rations. We move carefully through the now trashed tunnel, there are still booby traps and mines down here and only one cleared path. The analogy to Vietcong fighters, hiding from US warplanes in their tunnels 60 years ago, is astonishing. It must really be that war never changes.

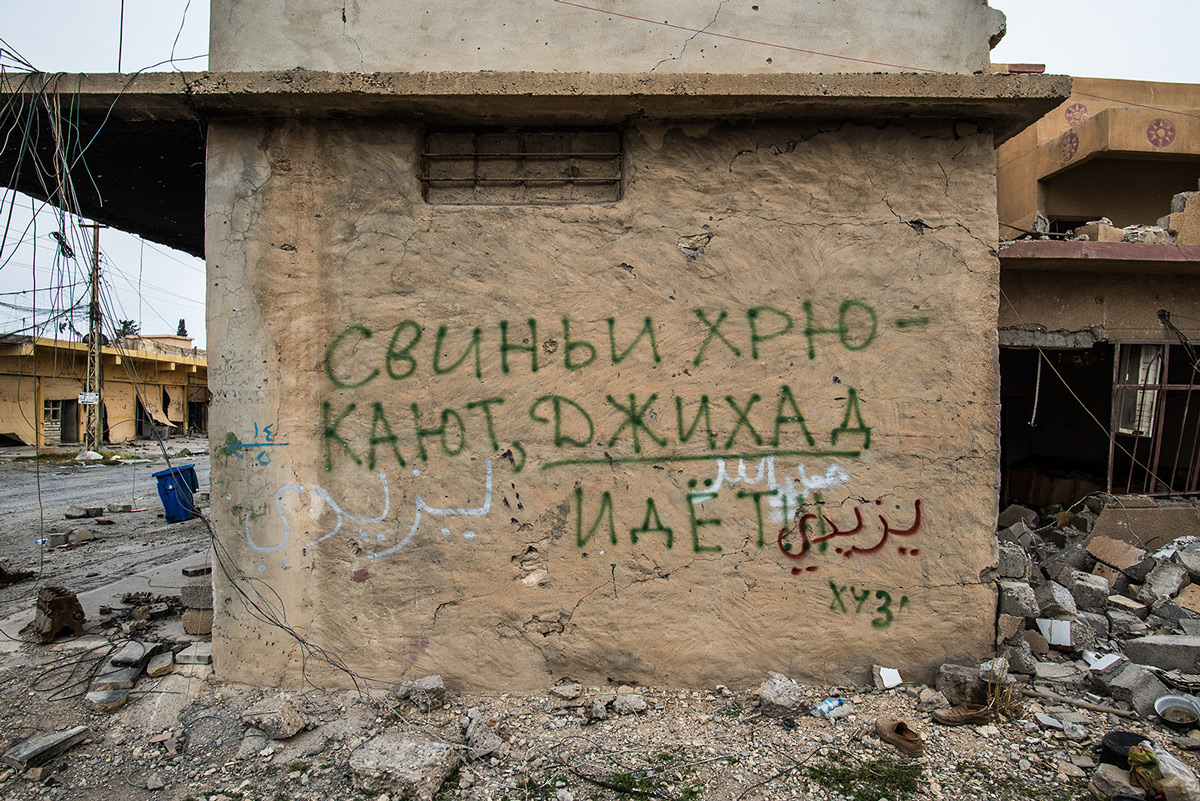

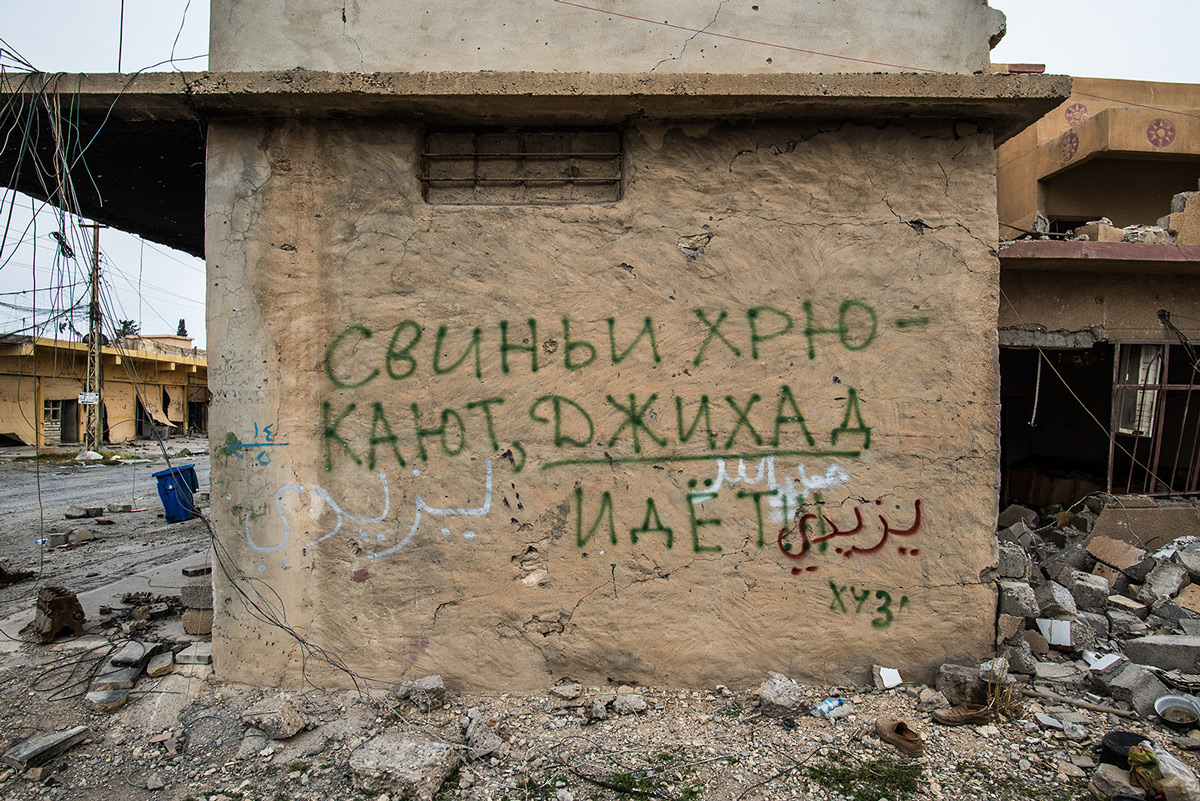

We emerge from below the surface into a half-collapsed kitchen. On a wall in the yard, a Russian-speaking ISIS fighter has written in green spray paint on a wall: “The pigs are oinking – Jihad is coming!”. A few meters away lays a burned body next to an old television set.

We slowly pick our way through the leveled town center to see the frontlines surrounding Sinjar. Here, Kurdish forces backed by coalition airstrikes are clashing with ISIS fighters on a daily basis. Northern Iraq can get very rainy and cold in late December. Overcast and foggy weather leads to a lack of accurate fire support from the sky, giving ISIS the confidence to probe the Kurdish lines.

Frontlines are boring places, soldiers are more in the business of killing time than other humans. Until something happens, then literally all hell breaks lose. And then before you know it, bullets stop to fly and pulses almost audibly go back to a normal rate.

Bullet sprayed buildings, a line of sandbags with frequent dugouts — here lies the frontline separating reclaimed Sinjar from the claimed Islamic State. And in the distance, as if someone has placed a huge mirror in the middle of the threatening calm-looking no-man’s-land, a line of sandbags with frequent dugouts and behind, the bullet sprayed buildings belonging to the opposing side. The only visible differences in these almost identical setups, are the colors in the raised flags on each side. One with the dominant red, symbolizing the blood of the martyrs of Kurdistan. The other one is black, referring to the Prophet’s war banner with the white writing claiming that “there is no god but God (Allah)”.

A few hundred meters away, three mortar shells are landing in Kurdish positions. The sharp whistle sounds… then nothing, no detonation. A Peshmerga officer lifts my confusion. “Daesh (ISIS name in arabic) must have put the amateurs on the lines today, mortar shells are not going to detonate in the rain drenched muddy soil we stand in.” No more mortars are falling on our position today – the “amateurs” must have learned the lesson.

It’s past sunset now and we are back at the Peshmerga camp in the center of what’s left of Sinjar. I have time to reflect on the fate of this place. It is not clear yet if Sinjar will be rebuilt. The obvious obstacle is the severe destruction to the infrastructure that Sinjar has suffered at the hands of the air campaign. But there is also a deeper rooted problem. During the takeover by ISIS in 2014, many of the towns the Sunni Arab minority supported or joined the ranks of ISIS, turning on their former Yazidi neighbors. As a result of this, voices are growing louder to abandon Sinjar, and to build a new exclusive Yazidi town, to avoid that Sunni property owners can return and reclaim their land.

The rise of ISIS catalyzed the alienation between ethnic and religious groups on a massive scale, sadly reducing the survival chances of Iraq as a state. Looking only at the microcosmos of Sinjar, one can get the impression that to get rid of the cancer the patient had to die.

New and best