Her Highness the Сoincidence: How World War I and Marlene Dietrich Helped Create One of the Largest Libraries in Europe

‘At the beginning of the 20th century, located only three hours from Paris, Normandy’s main port – Le Havre. Here yesterday’s passengers of transatlantic liners took their trains to Paris. One of them will later call the French capital a moveable feast that always stays with him. Another passenger, Miss Stein, for instance, after her arrival will create literary salons, her neighbor from the second car, Miss Beach, while travelling will definitely think about her own Shakespeare and Co. bookstore and library. In the cobwebs of the same train, the writers Zelda and Francis Scott Fitzgerald, were gathering the roaringest and tenderest thoughts of the upcoming Paris adventure, The New Yorker’s correspondent Janet Flanner was writing her essays and the famous actress Marlene Dietrich was looking through movie scripts. In the last car of the same train, I’m also heading to Paris reading the first 1923 issue of the French-American magazine Ex-Libris and not even noticing that I’m actually in one of the American Library’s rooms in Paris in 2017.

The American Library hasn’t changed practically since the moment of its creation in 1920. Situated in a typical Haussmann mansion on General Camou Street, 600 meters from the Eiffel Tower, it protects the legacy of the three previous locations, which were not far from The Elysée palace, Parc Monceau and Arc de Triomphe. And this is what creates the illusion of a train journey where passing from room-to-room, car-to-car, epoch-to-epoch you unconsciously participate in the lives of the people you met here.

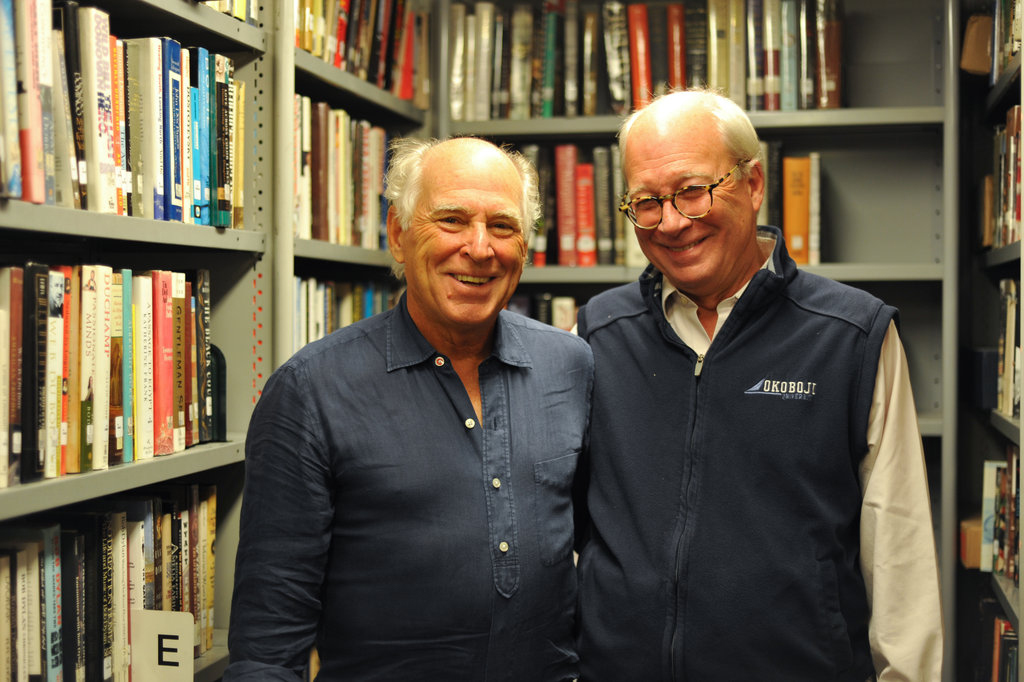

The Library’s director and The Washington Post’s former correspondent Charles Trueheart becomes my history train conductor, or maybe better to say, a guide.

— This job sort of accidentally happened, — he admits. — I’m not a librarian, but in my early journalism career I had covered literature and written about authors and publishing. So I’ve been here 9 years now and the library is doing well.

Later, I will understand that almost everything in this library is sort of accidental, including its creation.

Light of Books and John Kennedy’s Favorite Poem

The journey begins with the library’s archives.

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

This is how the 35th US President John F. Kennedy’s favorite poem, I Have a Rendezvous with Death, ends. This is also how its author, a Harvard graduate and the French Foreign Legion soldier, Alan Seeger’s life was cut short. And that was how, because of the war and Alan’s death, the American Library in Paris was created.

In 1917, when the US entered World War I, American libraries and households donated more than 2 million books to the European-based armed forces. Through the American Library Association War Service, these recently landed volumes were roaming the continental military camps for more than a year. In 1920, all the donations found shelter in Paris with the establishment of the American expatriates library. It’s difficult to say today why Paris was chosen as the main European book storage. More likely, it was due to the military camps’ French location, and as the growing American presence in Paris strengthened at the end of the 19th century by the newly created school, church, and newspaper.

The first 50,000 francs the Library received were from Charles L.Seeger, father of the very same Alan whose rendezvous with death took place in 1916 in France. Seeger Sr., who later became the first elected president of the Library’s Board of Trustees, had thus paid tribute to his son and volunteer soldiers killed during the war.

Our conversation continues in Director Trueheart’s office where he shows me one of the rare old books. “After the darkness of war, the light of books” its ex libris, or a bookplate says. It turned out to be the Library’s motto that remains relevant even today.

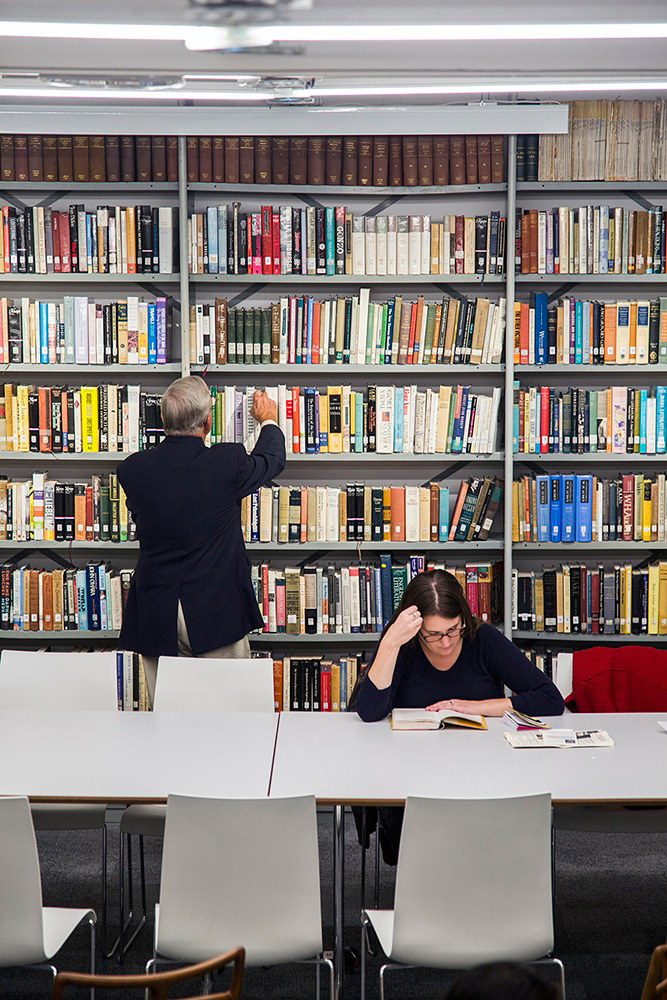

– That’s the original logo (Charles shows me one of the Library’s posters). We used its modified version in the first years that I was here, but I had to cut it in half because on the other side there was a gun. Anyway, yes, it’s always a very relevant statement. One of the ways to overcome conflicts is by educating ourselves, not just listening to other people’s opinions…We have very few rare books in our collection. It would be nice if we had more, but you know how libraries work. If you’re in 1927, you wouldn’t care about throwing away a book that was six years old and getting another one. So, by natural selection, we don’t have very many like that. We don’t make a fetish of books, mainly, we try to have books on the shelves that would be useful to people.

Camp reading room, 1919

With the Lost Generation

A fuss is being made over her. “And how not to make it,” I’m thinking on the way to the next room (and in the Roaring Twenties), “when in 1922 Gertrude Stein becomes a Library subscriber.”

The thing is that before she had borrowed books from Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Co., the main English-language bookstore and library in Paris at that time. But when Sylvia Beach, as its owner, decided to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses, Stein’s ego was incredibly bruised. According to Hemingway, she couldn’t even hear about Joyce, bringing up his name meant a lifelong exclusion from her salon. So that’s how, entirely by accident, Gertrude Stein became the American Library’s reader.

She didn’t come alone and brought to rue de l’Elysée Ernest Hemingway. The A Moveable Feast author was reading and even reviewing literature in the Library’s monthly edition, Ex Libris. Created in 1923, this review was a typical cultural magazine where articles about Shakespeare, Le Grand Cafe’s regulars, and American history normally co-existed. New arrivals and French books releases were also under the watchful eye of the edition’s reviewers. As well as advertisements that had a special place on the Ex Libris pages: American Express, for example, in the publication titled The Woman, Traveling and Her Money appeals to female forgetfulness and clumsiness abroad, and as a solution the company offers to buy its travelers cheques. Coca Cola, on the other hand, in its advertising reassures that your soda will find you everywhere, at a hotel, club or café.

Today, The Library’s newsletter has exactly the same name, Ex Libris, and exactly the same purpose: inform while reviewing. In the 1970s, it was decided to launch a new edition, The Paris Observer. But this magazine published in the same style and format lasted only six months and was subsequently closed.

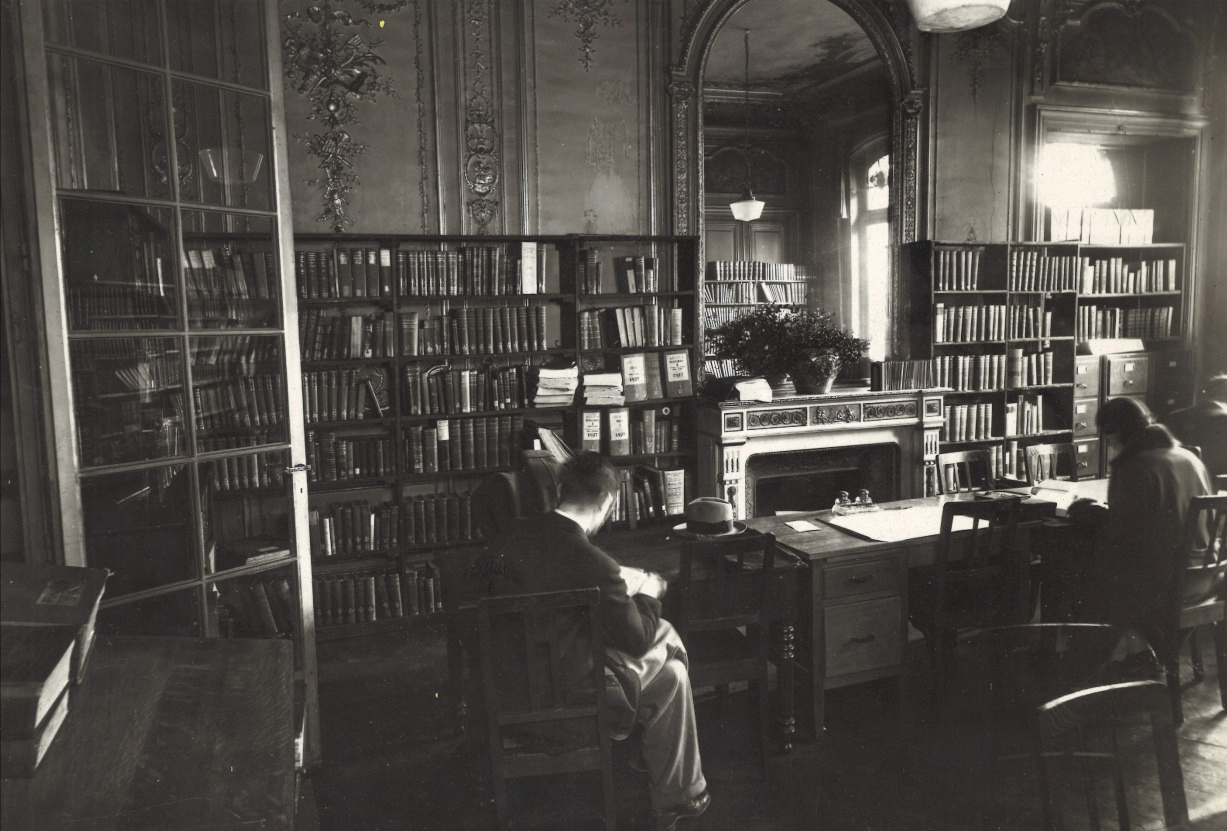

Reference desk and reading room at 10 rue de l’Elysée

To a certain extent, the American library was the main competitor of Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia Beach’s bookstore and library. But when during the Nazi occupation Sylvia Beach refused to sell one of James Joyce’s books to a German soldier, Shakespeare and Company’s fate was sealed. The bookstore-library was closed and The American Library therefore became an English-language literature center.

– But it’s worth remembering, – says Trueheart, – that in the early decades the primary audience of the Library was French people who didn’t have access to English-language books. Nonetheless, since it was a place where Americans gathered, it also attracted writers.

In 1933, with the creation of the Writer’s Program – a forerunner of Evenings with Authors – literary figures such as Henry Miller, Colette, and André Gide start frequenting the library. Henry Miller, author of the erotic novel Tropic of Cancer, even became an active reader. As we can see from his letter to the Library’s Director Dorothy Reeder, he was particularly interested in Zen Buddhism, Balzac, and The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Cherchez la Femme

During World War II, The American Library in Paris remained open and shipped 100,000 books to British and French soldiers. At that time it was even being called “an open window on the free world”. Nothing has changed since the war. The Library has opened several branches on the Left Bank of the Seine, in Roubaix and Angers, which were, however, later closed.

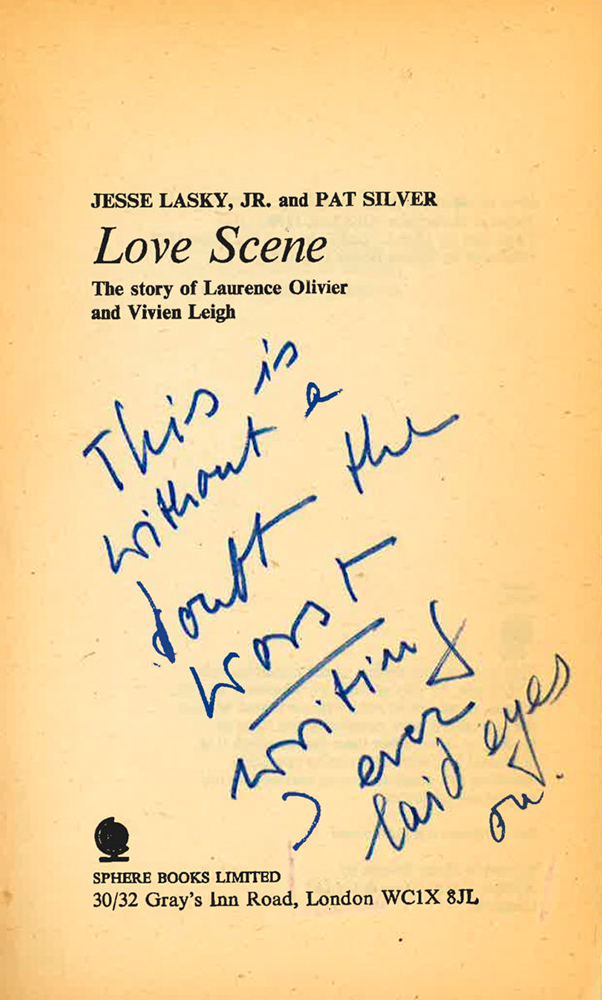

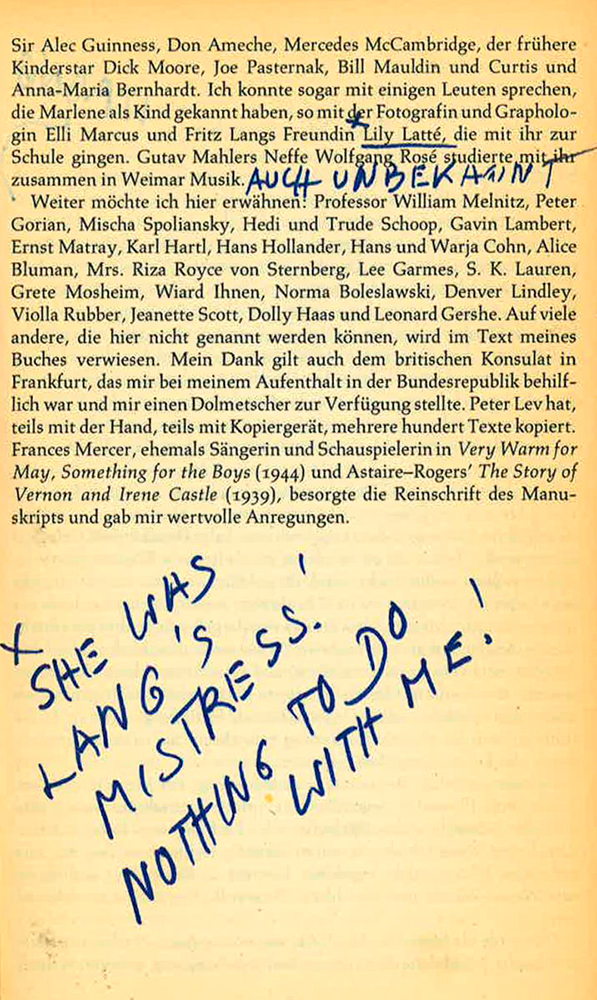

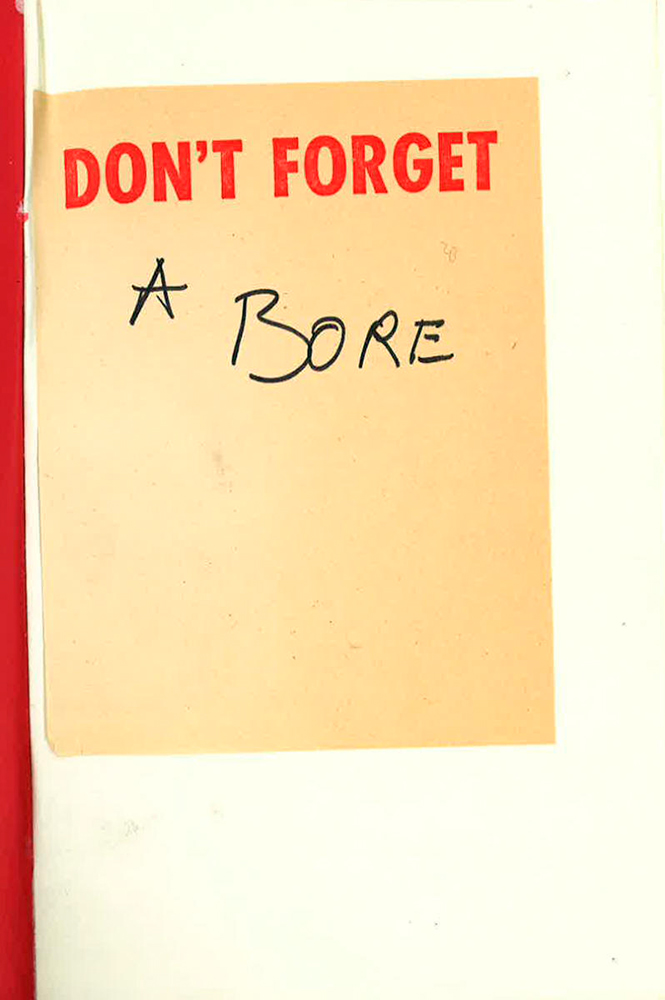

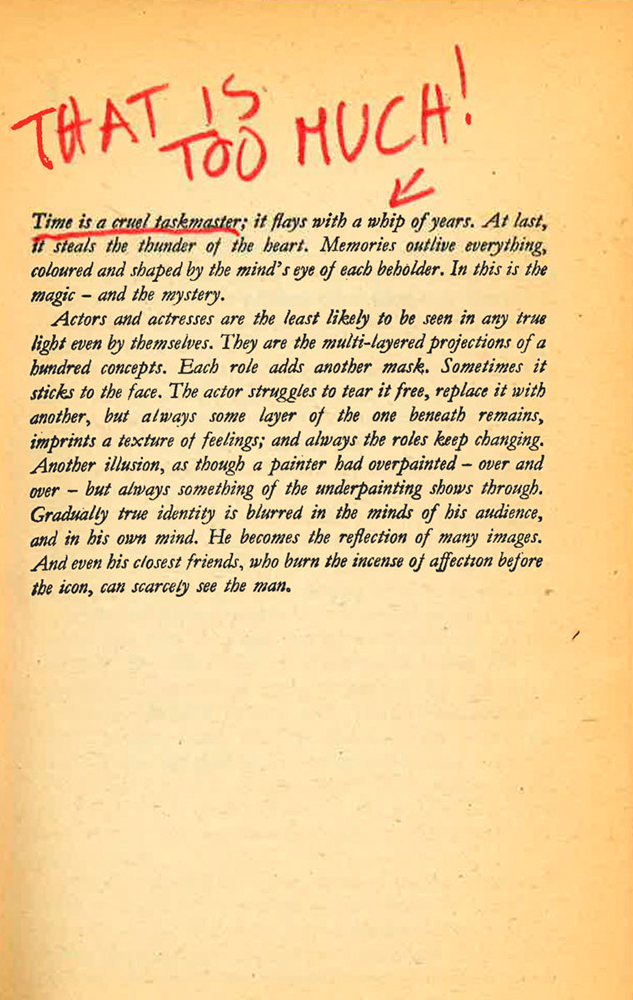

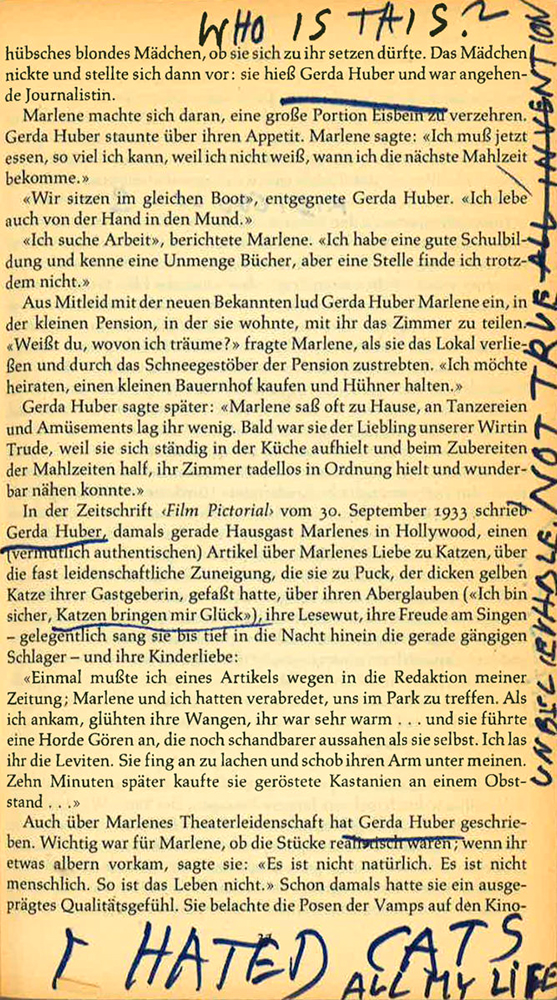

I walk into the next car, the private collections department, where I meet the very same Sylvia Beach, who after the Shakespeare and Company closure donated 5,000 books to the Library, French composer Nadia Boulanger and the New Yorker’s correspondent Janet Flanner. But apparently the most interesting passengers here are Marlene Dietrich, her books and varicolored comments in the margins.

Director Trueheart explains that in 1992, after Dietrich’s death, her grandson, Peter Riva, called the Library and offered 1700 books from her private collection. A truck arrived the next day and the movie star’s pearls of thought moved to the General Camou Street.

While looking at her photo in one of the books, Marlene asks herself: “This is travesty?” Reading her biography in German, she denies her love for cats and states that she has nothing to do with Fritz Lang’s mistress. In Eddie Fisher’s memoirs Dietrich finds several romantic comments about herself and, of course, doesn’t leave them without attention: “I said it! We never met!” She calls Heinrich Mann, the author of the book Professor Unrat, the movie adaptation of which, The Blue Angel, became emblematic for her, “a sad man living in the shadow of his famous, highly talented brother!” and takes an interest in Ilf, Petrov, and Olesha’s novels.

The largest English-language library in continental Europe prepares to celebrate its centenary by running a book club, and by giving out a book award and a visiting fellowship. The American Library also doesn’t hide the pride for her Paris address: “What I really appreciate here is this feeling of being a visitor, I feel like I’m living for more than adventure.” As for me, the American Library leaves a similar impression: where else would you travel alongside Gertrude Stein, leaf through a magazine with Hemingway, and read a copy of One-Storied America owned by Marlene Dietrich?

Translated by Olesia Tytarenko

Jimmy Buffett and Charles Trueheart. Photo: Crystal Kennedy

New and best