Whalers, Reindeer Herders, and Mushrooms: The Russian North in Andrey Shapran’s Project

Born in Latvia, lives in Novosibirsk. Professional photographer, member of the Russian Union of Art Photographers. His works are not only in private collections, but also in the State Russian Museum (St. Petersburg) and Novosibirsk Museum of Regional Studies. He has been studying the Russian North since 2005, working on his project called Lands at the Edge of the World — a series of photographs from South Kuril Islands, Kamchatka Peninsula, Chukotka region, Yamal Peninsula, Taymyr Peninsula, and Dudinka.

The Tundra

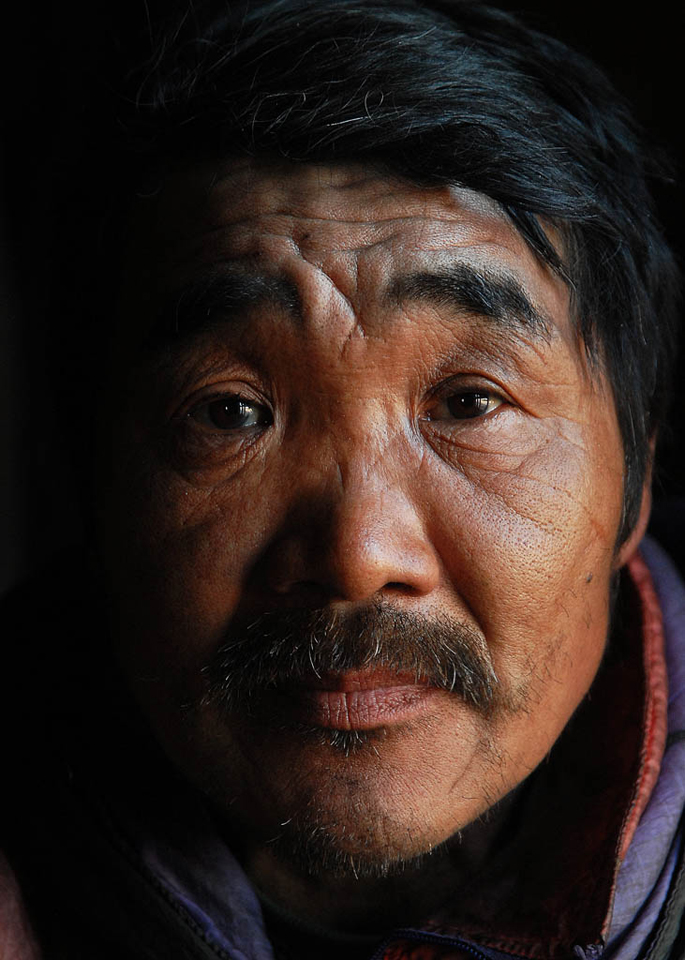

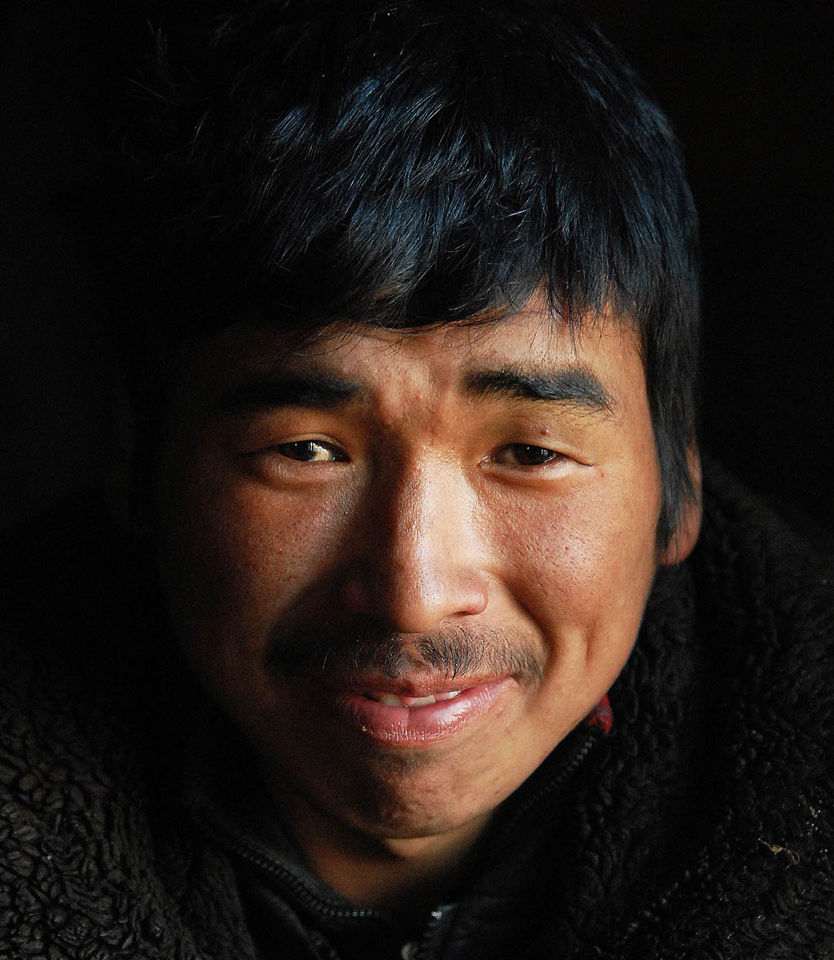

Grandpa Pikul, a mentor for young reindeer herders, told me that before perestroika, which in Chukotka they for some reason call a ‘revolution, there were 11,000 reindeer on their collective farm. By mid-1990s there were only 1,500 left — the former collective farm was often visited by merchants who offered a bottle of vodka in exchange for a reindeer. A box of vodka cost twenty heads.

— We needed the reindeer, of course, but then again we needed vodka, too. The time we lived in made us like this! — grandpa Pikul regrets.

Currently there are 4,000 heads of reindeer in the herd.

The former collective farm has two cross-country vehicles that migrate around the tundra together with the herd. When it gets colder, the SCVs return to the settlement, and deer herders hide in their yaranga mobile homes. Winter is the most difficult time on Chukotka — the blizzards are fierce, and polar wolves come out of the woods.

Grandpa Pikul was in Moscow in the 1970s. He was unimpressed: the Red Square is small, and our Tundra is bigger. We, the Northern people, measure everything on a different scale.

If you close your eyes and listen, you feel as if you were on a different planet. But then you open your eyes again, and see that you are still here, in the tundra. Just like centuries ago, the reindeer migrate, and people follow.

At night, we see the clouds cover the stars as we speak. Anatoliy, the herder, says the clouds are a blanket. The sky takes pity on the herders — under the clouds, the Tundra is not that cold.

A rumor about two lone wolves on the mountain pass is moving around among the herders. The Chukchis told me those wolves were scouts, which means the whole pack would be there soon. Wolves are afraid to attack the herds during the day. But at night, the only things that can protect against attacks by predators are a gun and a burning fire.

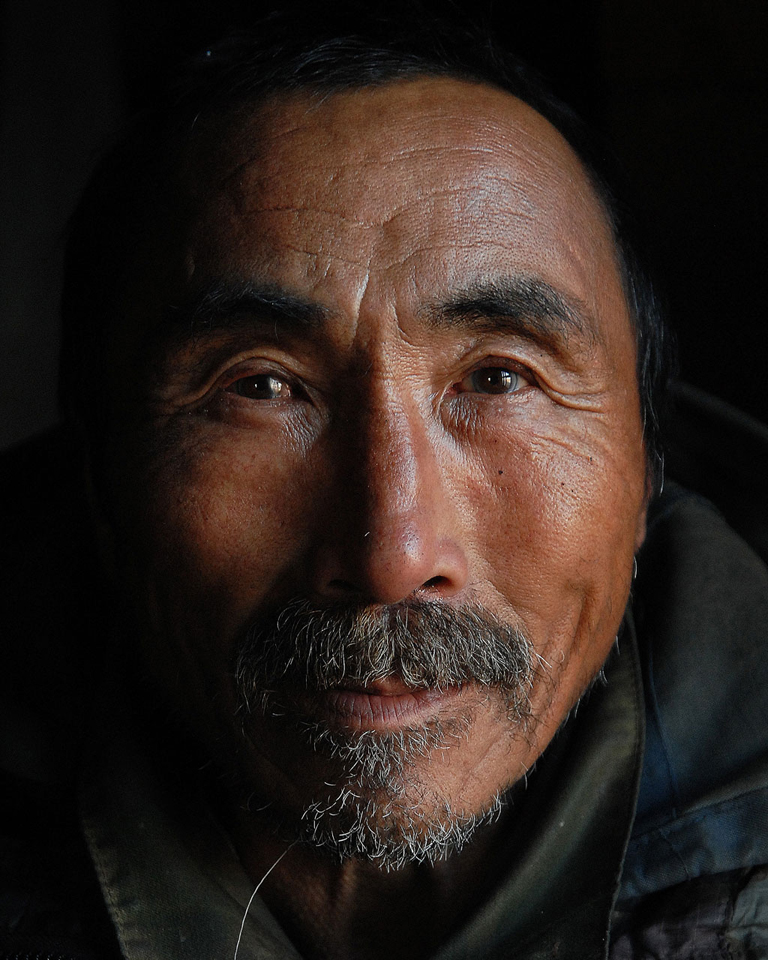

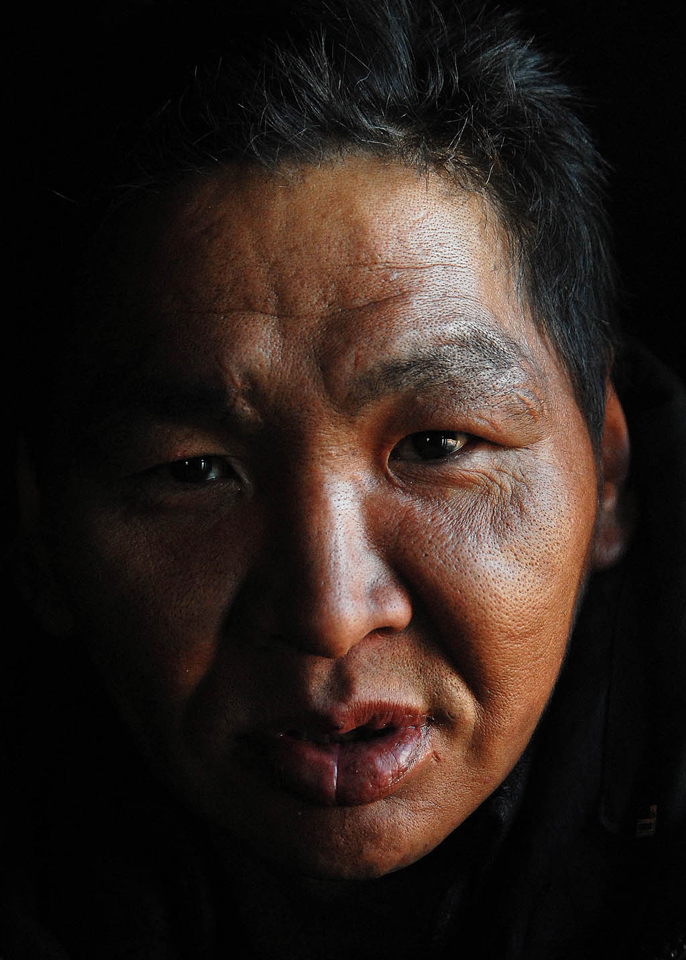

Volodya Tankay, a foreman, told me a story about how it rained in 1997, and all the mountains turned into an ice rink. That year Chukotka lost 150,000 reindeer, and they lost half of the reindeer they had. Tankay is 47, his parents are Chukchi, who came to Kamchatka from Chukotka together with the reindeer. He usually weighs about 70 kg, but now he is no more than 60 — he has to go hungry and run around after the reindeer all the time. This year, he had to do the work of three.

How many kilometers does he walk with the herd every day? Tankay says, not less than 50.

He walks on the off-road, in Tundra, in the mountains away from the passes. “I walk the distance round the globe in a year” — he laughs.

Facing the wolves at night is much more difficult than walking, though. Tankay is sure that the wolves can hypnotize a human from a distance. It happened twice that he was sitting by the fire and didn’t even notice how his eyes closed. He woke up because his own herd was trampling on him. When wolves attack, reindeer hide behind the back of humans. Tankay jumped up, started screaming and waving his arms, but it was too late — the wolves have already gotten one reindeer.

The Sea

Gennadiy the hunter was cutting meat off the head of a freshly killed whale.

It was a grey whale — the locals say those are fighters. A grey whale can easily turn over a boat with the hunters. The distance to the shore is usually not less than 10 kilometers, and if there are no other boats around, there is no chance to avoid the whale’s attack. Gennadiy says that whales attacked their boat twice. One time a wounded whale dived and pushed the bottom of the boat with his head — all hunters were out of it and in the water at once. The second episode was less dramatic, and after the attack the boat remained afloat.

Going out into the sea is scary, but you can’t do without it. Whale hunting is almost the only profitable thing in the region. In the summer, during the season, the whalers get about 30,000 RUB (currently about 420 USD). In the winter it’s less: there a few animals and there are none to hunt. A year ago Gennadiy found a job as a warehouse watchman, but he says the sea was stronger — it pulled him back.

Today the boats went towards the strait. Because of the thick fog we could see nothing but grey sea water. After forty minutes, the first whale showed up. We had a couple unsuccessful throws of the harpoon, and he left. After some time, we saw the other one at the horizon. The chase lasted for no less than two hours. The whale went further and further into the sea, but he couldn’t break away from us at that point — he was all covered in harpoons. There is a red or white plastic ball at the base of every harpoon — a sign for other hunters. If the whale breaks away and goes into the sea, the other hunters will later see he is wounded, which means they can shoot from a rifle, to kill.

Our whale tried as hard as he could to escape to the sea. He was literally covered in those balls, like a Christmas tree. It felt like a holiday and a tragedy at the same time.

By lunchtime the hunt was done. We had more than 20 kilometers to the shore, which meant that our way back would take no less than 5 hours. We were afraid we’d run out of fuel.

Ottoy, the hunter, asked me:

— Have you seen the eyes of the whale?

— No, I haven’t. We were not this close. Have you?

— Yes.

— What’s in them?

— Pain, only pain. This is the way the Northern trade is, though.

And so we went to shore like this: three boats and a huge whale in tow. We stepped on the ground at dusk, and when the hunters started carving the whale, the white moon was up. A silent Northern coast, people are fussing on the sand beach, where a skinned carcass lies.

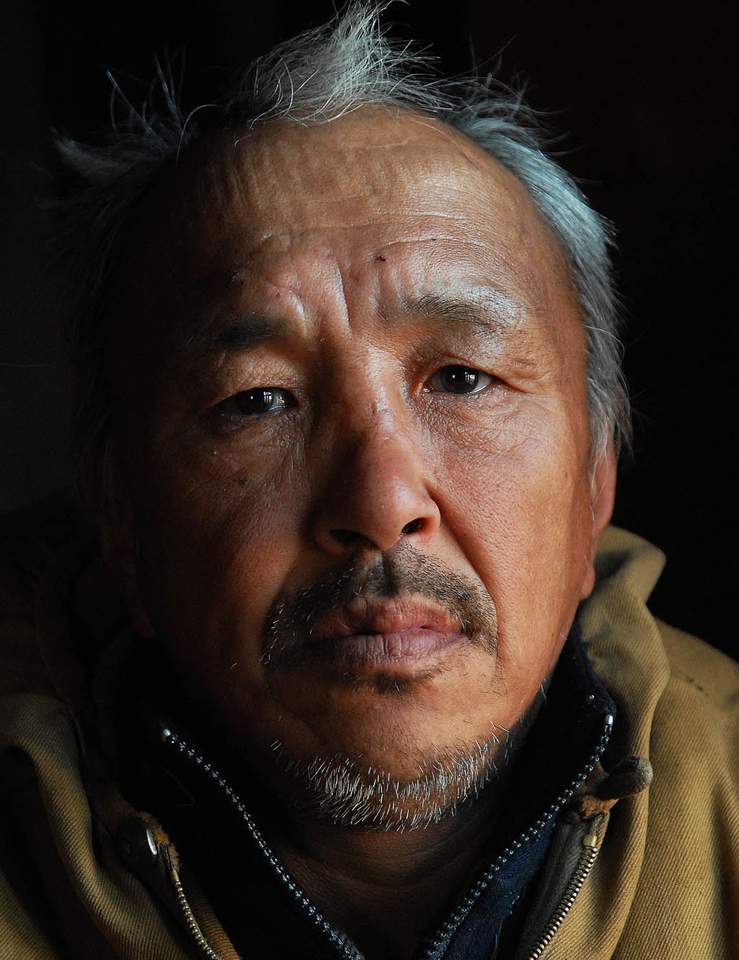

Reindeer herder Grandpa Pikul was standing by my side and saying apologetically:

— If he came to us, we have to take his meat. In the Tundra I am a master, I am always full — but it is not like that in the settlement.

Hunters say: in the summer the sea takes our heat, in the winter it takes our cold. There are no great frosts on the coast, only blizzards and winds. Chukotka wind never drops.

Mushrooms

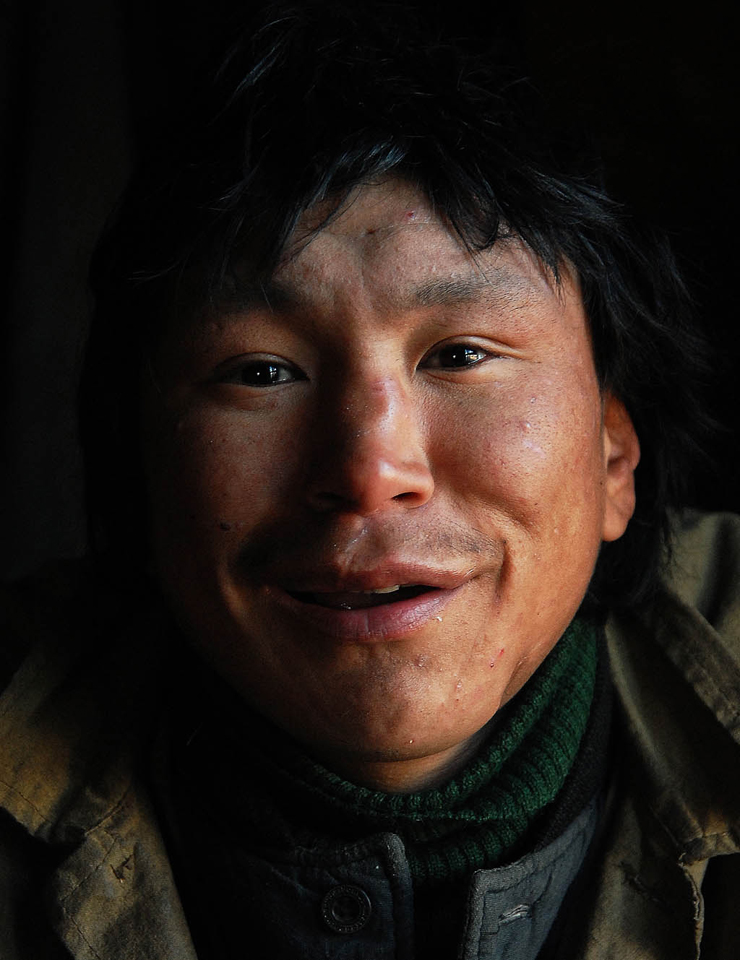

In the morning Anatoliy Yetylyan, the herder, was telling us enthusiastically, how he was arguing with the host of the cooking show at night.

— He has been trying to make me change my mind all day, but I won anyway!

Anatoliy is in great spirits. He woke up first, got the stove going, warmed up tea, cooked rice, and got busy sorting through amanita mushrooms.

— Anatoliy, do people get a mushroom addiction?

— They do. I have it.

Volodya Tankay adds that crafty mushrooms do weird things to people. “Do you want some?” I refuse. He is surprised and says that usually tourists don’t have to be asked twice and are open to experiments. One and a half mushrooms didn’t hurt anyone yet.

— I am not going to have any now, Volodya, — I tell Tankay. — If I eat it now, I won’t find my camera in the Tundra by the night.

— You may be right, — Tankay sighs. — People die from mushrooms, too. This was the way my friend’s brother died…

However, now Chukchi and Evenki think vodka is a greater evil than mushrooms.

Tankay says that no one in history, neither the Americans, nor the Russians, could conquer his people — but vodka could.

It’s night. Tankay is standing on his knees in the middle of the tent, swaying from side to side. Just an instant — and he takes his head in his hands and starts a strange song. It seems that the herders who are sitting in a circle have gone numb. None of them dares to stop him. Tankay is already in trance. “Ray-tyg-yr-gyn” — he mumbles, and says nothing else.

I ask the other herders:

— What is he singing?

— His name, — reply they together.

Tankay raises abruptly, walks around a circle, sits on the ground again, and continues singing. All of this lasts an eternity. Singing alternates with many-worded phrases, where Chukchi language is mixed up with Russian, it is impossible to remember them, and it makes no sense to ask the herders. Tankay is speaking very fast, as if someone is prompting him.

— See, Andrey, — he suddenly says, without even turning to look at me. — how crafty these mushrooms are.

He goes out to the Tundra, but the tension is still in the air. We still sit at the light of the only candle. After some minutes someone opens the tarpaulin curtain, and we see Tankay’s tall figure in the middle of our circle again. He starts speaking in a strange voice, it sometimes seems that he is coming back to his senses, but no, not yet.

Later he’d say me that on that night he went too far and could only see the herder named Yergun. Everything else was completely dark.

— Now you’ve seen it all, — Tankay tells me before I leave. — You can go with peace.