Loneliness, HIV, Death, Fame: Peter Hujar’s Gloomy Story

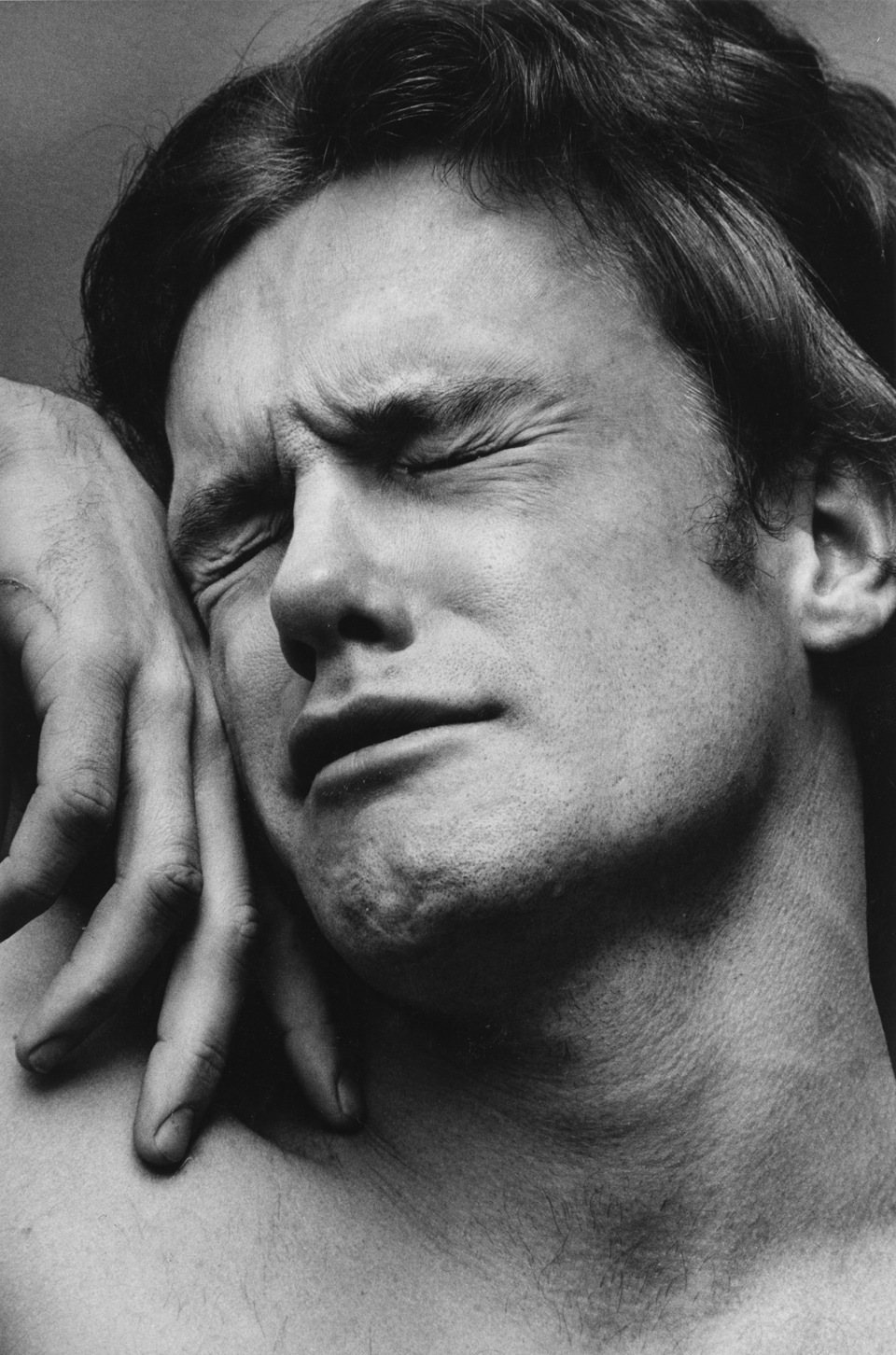

It all started in 2011 when Hujar’s photographs were included in the exhibition Night Vision: Photography After Dark in the Metropolitan Art Museum. Hujar’s genius was suddenly seen: collectors, museum professionals and gallerists suddenly acknowledged him. In five years, one of the works of the photographer, Orgasmic Man, was featured on the cover of the popular novel by Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life. Respected galleries started fighting for the rights to show the photographs of a newly discovered author, and exhibitions came one after the other. Hujar’s dream to become famous not only in a narrow circle of friends, but all over the world, came true.

Gays and Animals

Hujar grew up on a farm. His father abandoned his family before Peter was born, and the future photographer was raised by his grandparents. He started taking photographs at an early age and ran away to New York at the first opportunity. He came under the influence of Richard Avedon there and started working with fashion magazines — but with time grew to disdain glamour and gave that up.

Collectors, museum professionals and gallerists suddenly acknowledged him.

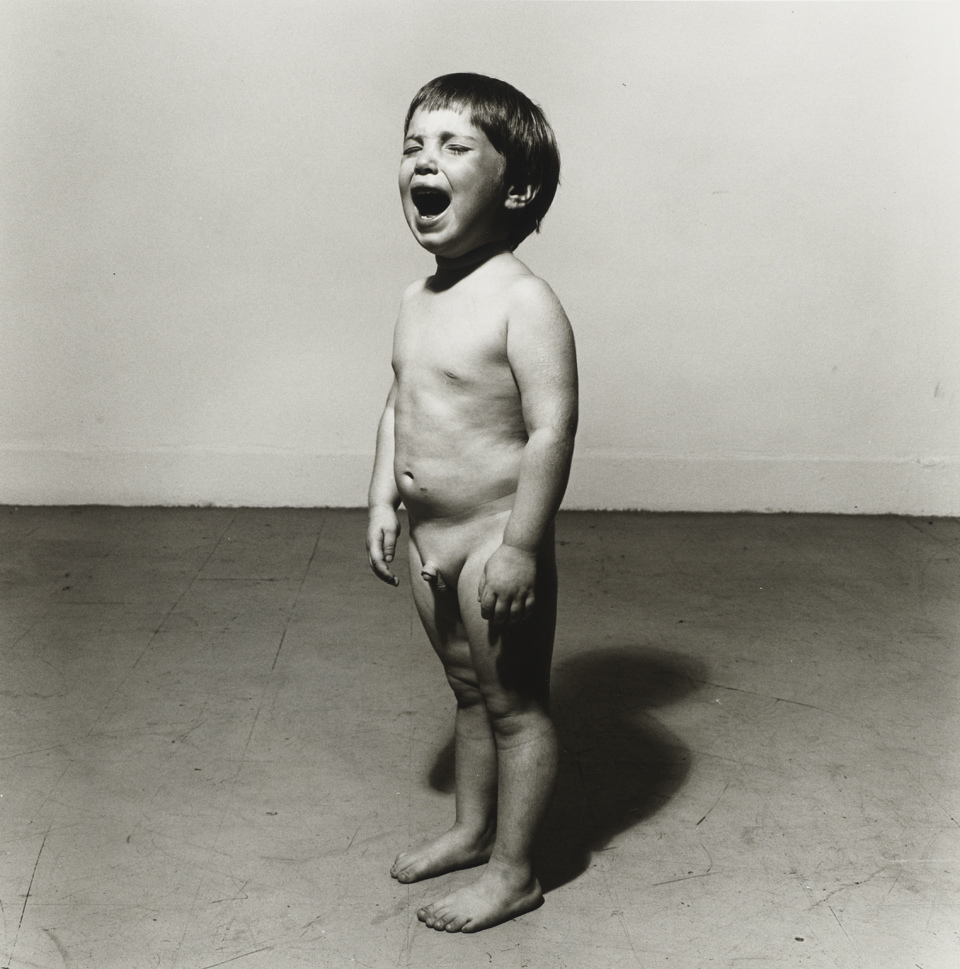

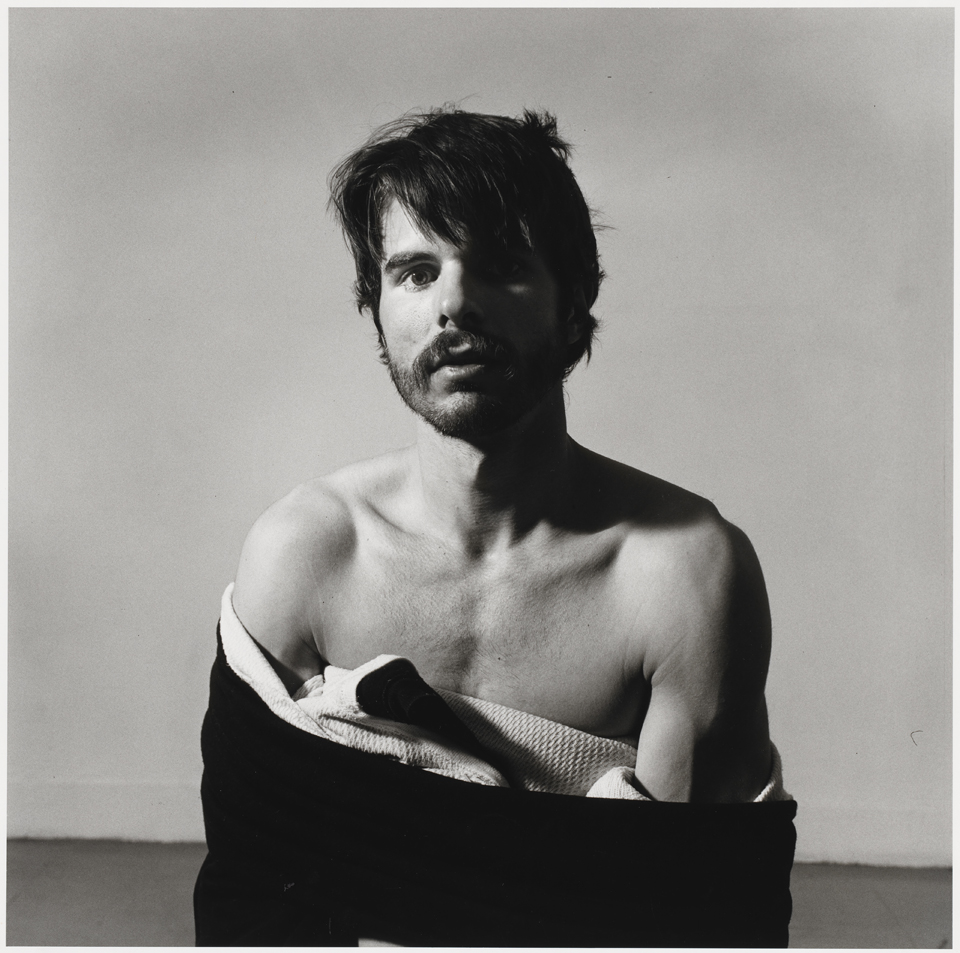

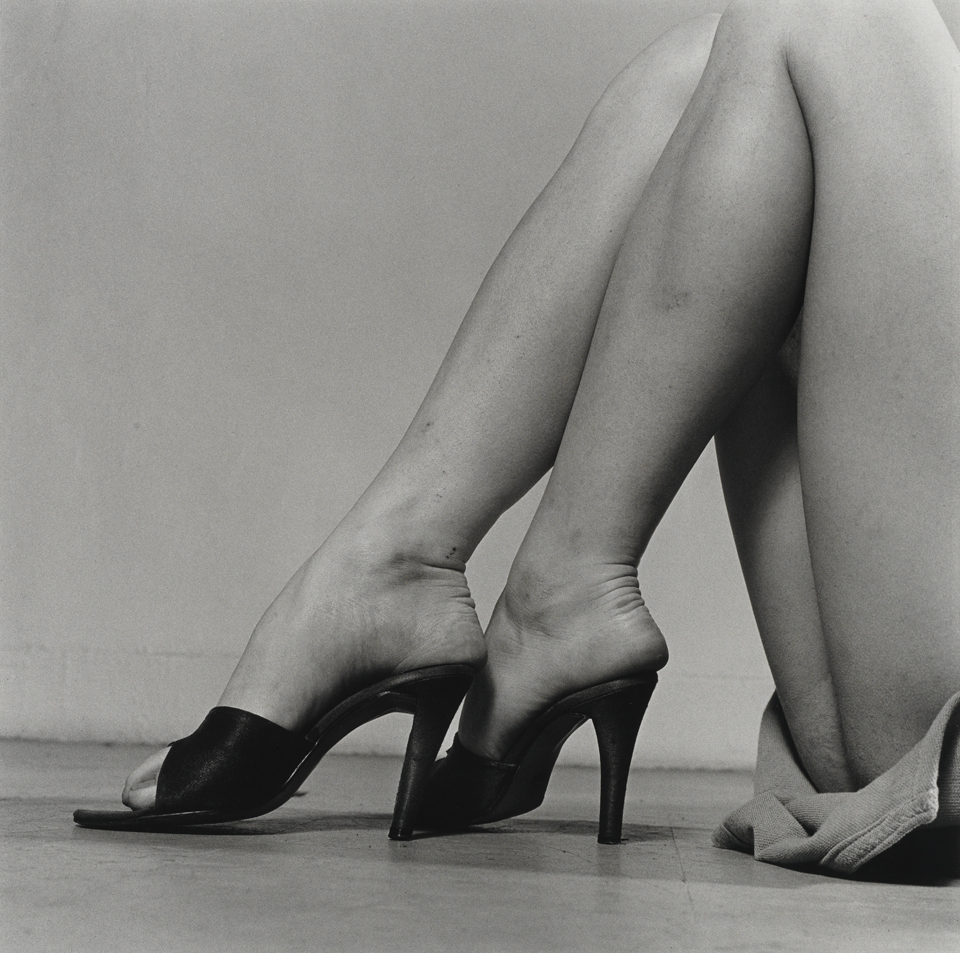

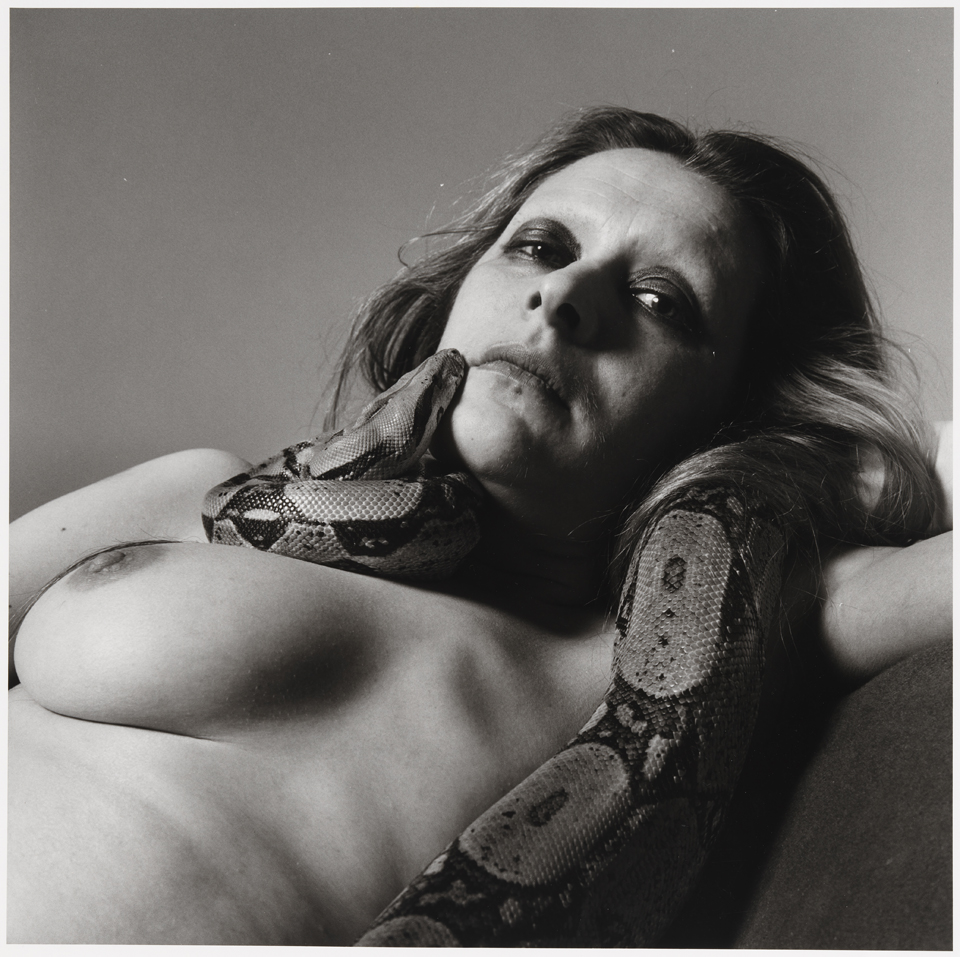

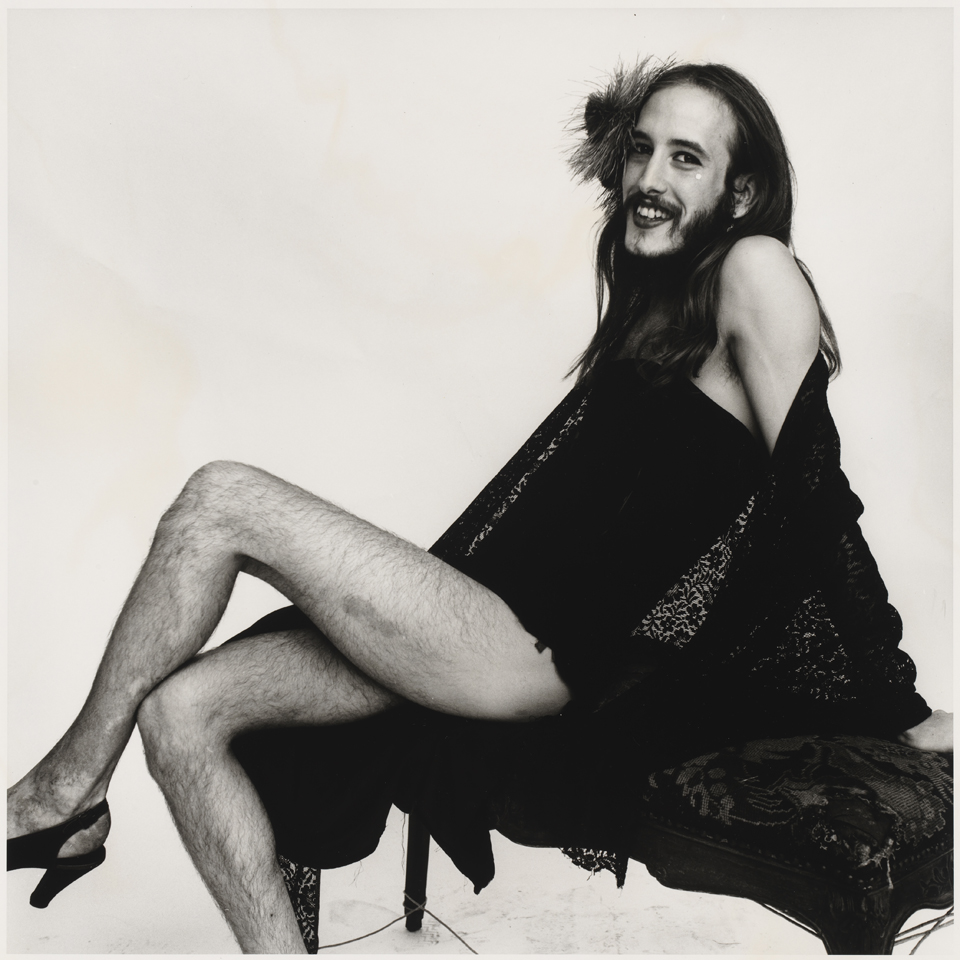

Hujar focused on photographing the life of people of his circle: he took portraits of friends and lovers (he was homosexual) and celebrities. Also, he loved pets and left behind many wonderful images of dogs, cows, horses, and other animals. However, he had no recognition: the audience liked neither naked men with obvious homosexual subtext, nor weird animals photographed like people. Hujar’s work didn’t interest art collectors, and museum curators didn’t look his way.

He was upset, but argued with those who tried to interfere with his creative process — because he couldn’t stand compromise. Like most of his models, Hujar contracted HIV, and suffered about not having enough time. He was communicative and brave, but always unsure of himself. “[there] was an incredible insecurity, an incredible sense of not getting where he wanted to be, and real anger at the way things were going in his life,” his friend Vince Aletti said. In addition, Peter was poor, and it also bothered him.

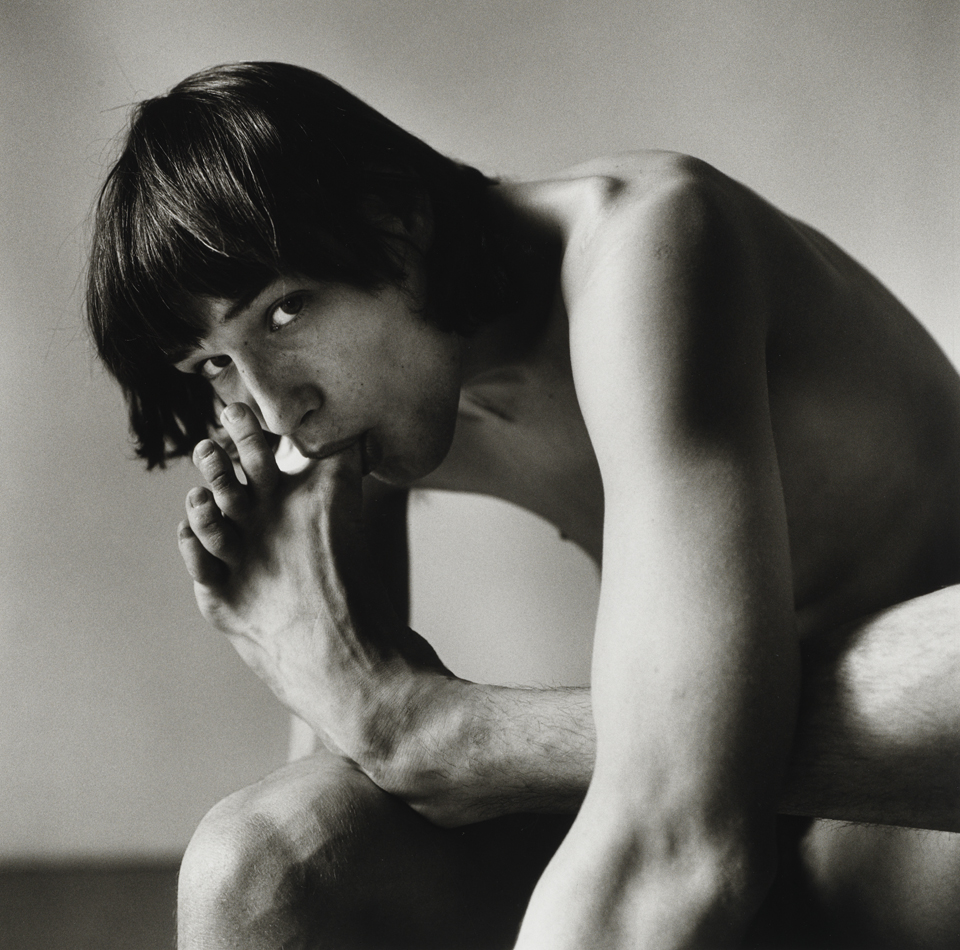

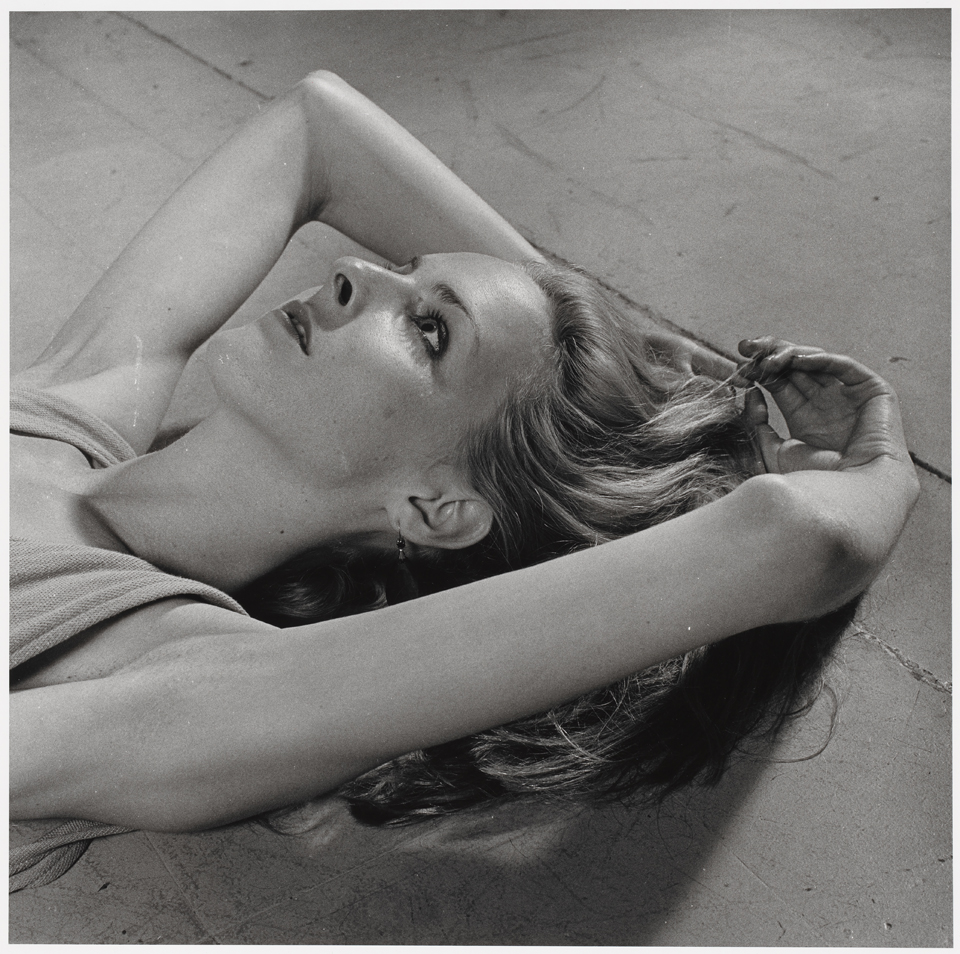

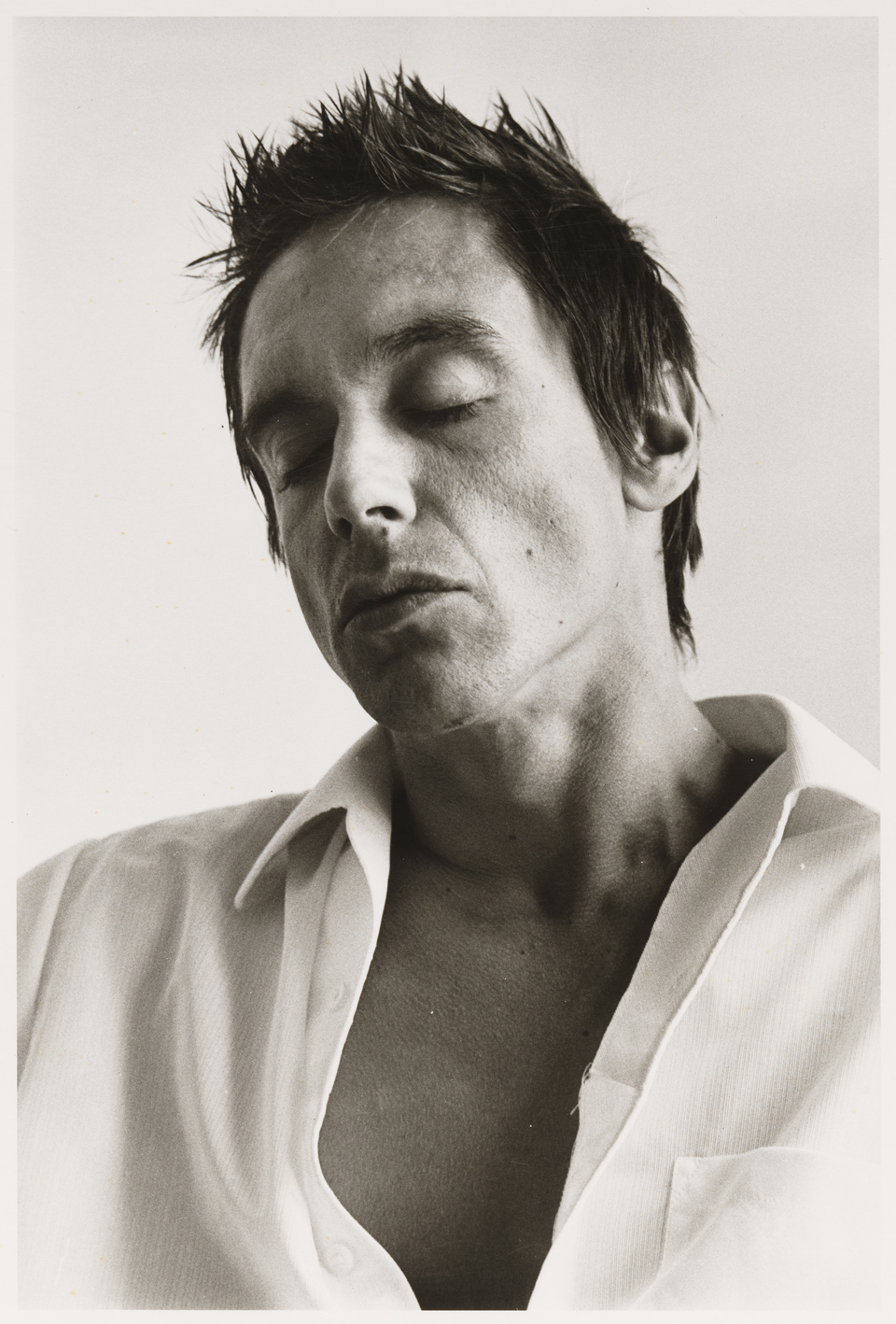

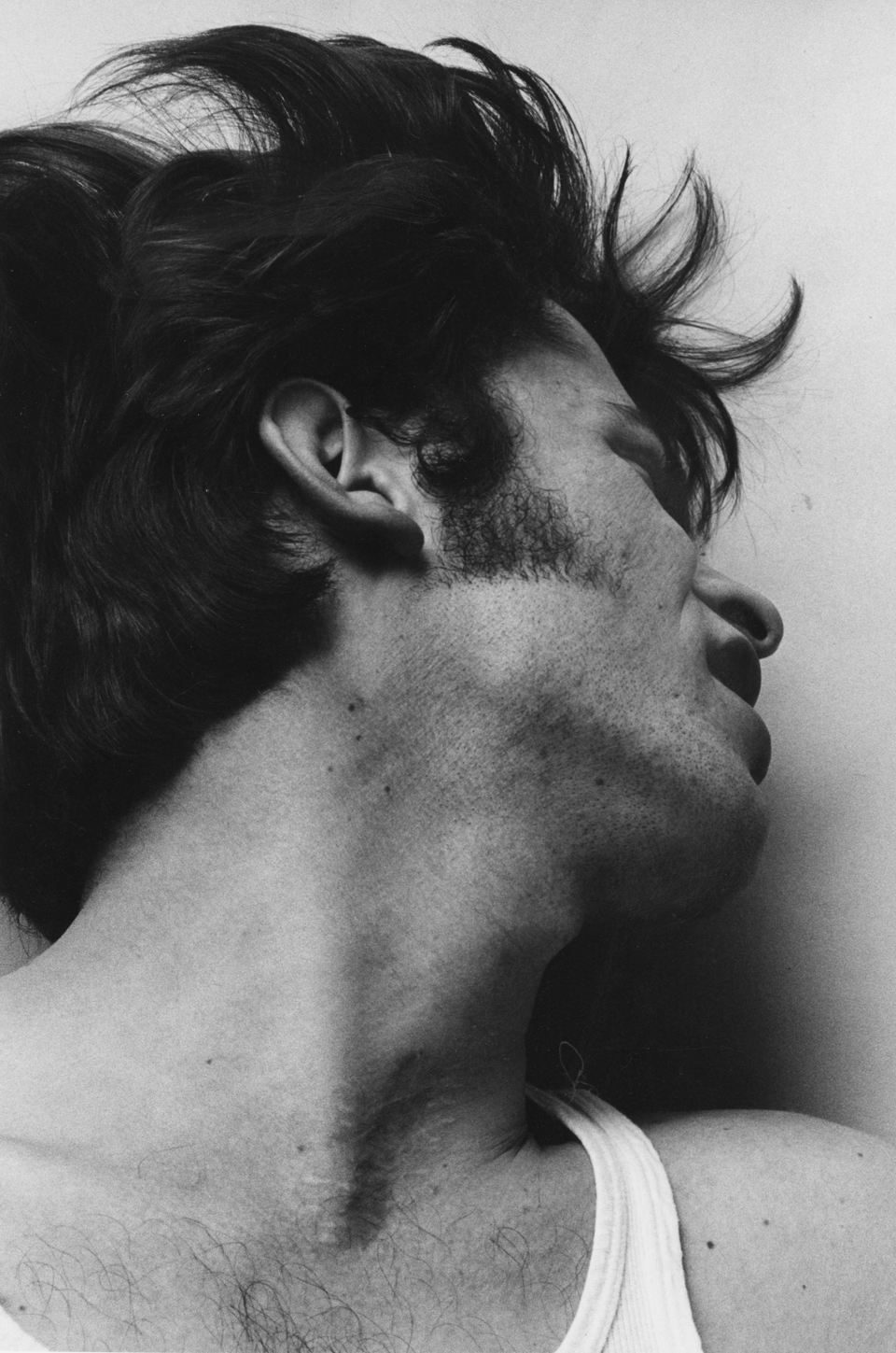

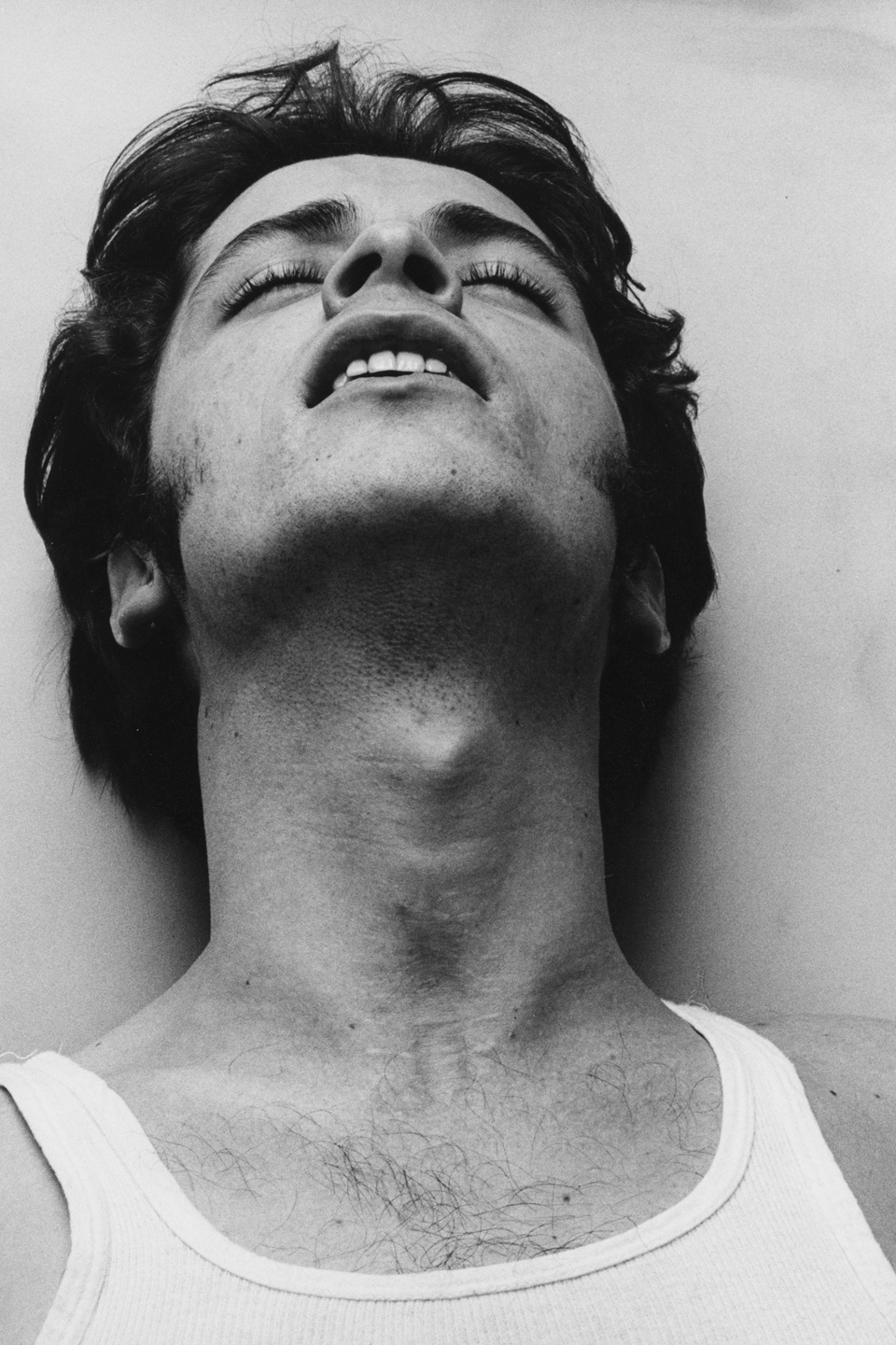

It could be that all of this mental torment refined his senses. For instance, when starting to work on a portrait photographer seemingly grew into a model, he tried to become one with the object of his creative impulse. Peter fell in love with the model, felt hatred, fear, and sexual desire. All of these feelings inside him were feeding on each other, and Hujar produced a very brief, sensual, and surprisingly deep image.

A photographer seemingly grew into a model, tried to become one with the object of his creative impulse.

Death Near Here

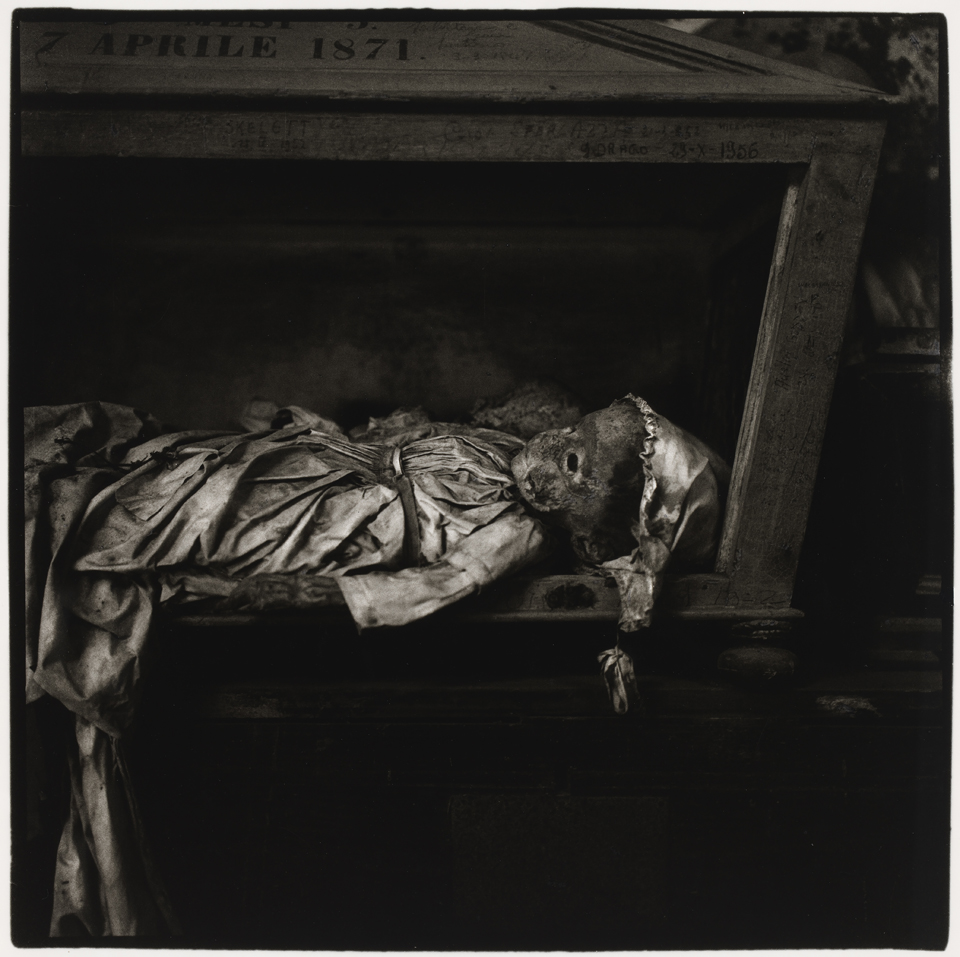

Only one book by Hujar was published during his life, and amidst the AIDS epidemic. The author called his album Portraits in Life and Death. Leafing through the pages, the viewer makes eye contact with ‘alive’ characters, and then falls into the bottomless eye sockets of skulls and stumbled upon rotten bodies from the Sicilian catacombs.

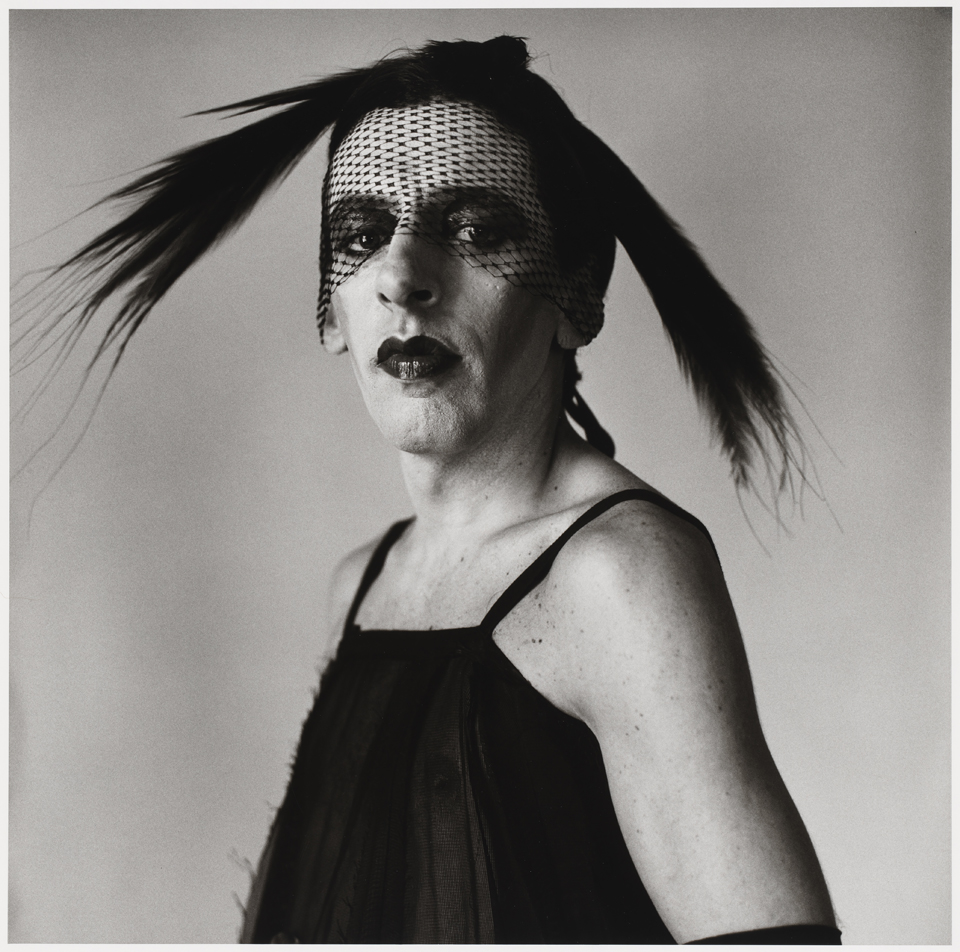

Critics said that Peter constantly felt the air of death and conveyed this feeling through his pictures. All is perishable, all is sad, all will rot, an end will come to everything, but in all of this space you can still have fund and quench the thirst with sickly sweet final orgy. And photography is a tombstone to all things, it will conserve something that will soon disappear. “Photography turns the whole world into a cemetery,” he said before Roland Barthes. It is considered that the ultimate expression of his perception of the line between life and death is the portrait of Candy Darling on her deathbed — the embodiment of the absurdity of being, the photograph of a live death. During the shoot, Candy put on a new death mask every time, unlike the one that death itself wore on her. Candy is still here, but already there, in a place where there is nothing.

Photography is a tombstone to all things.

Alone and Together

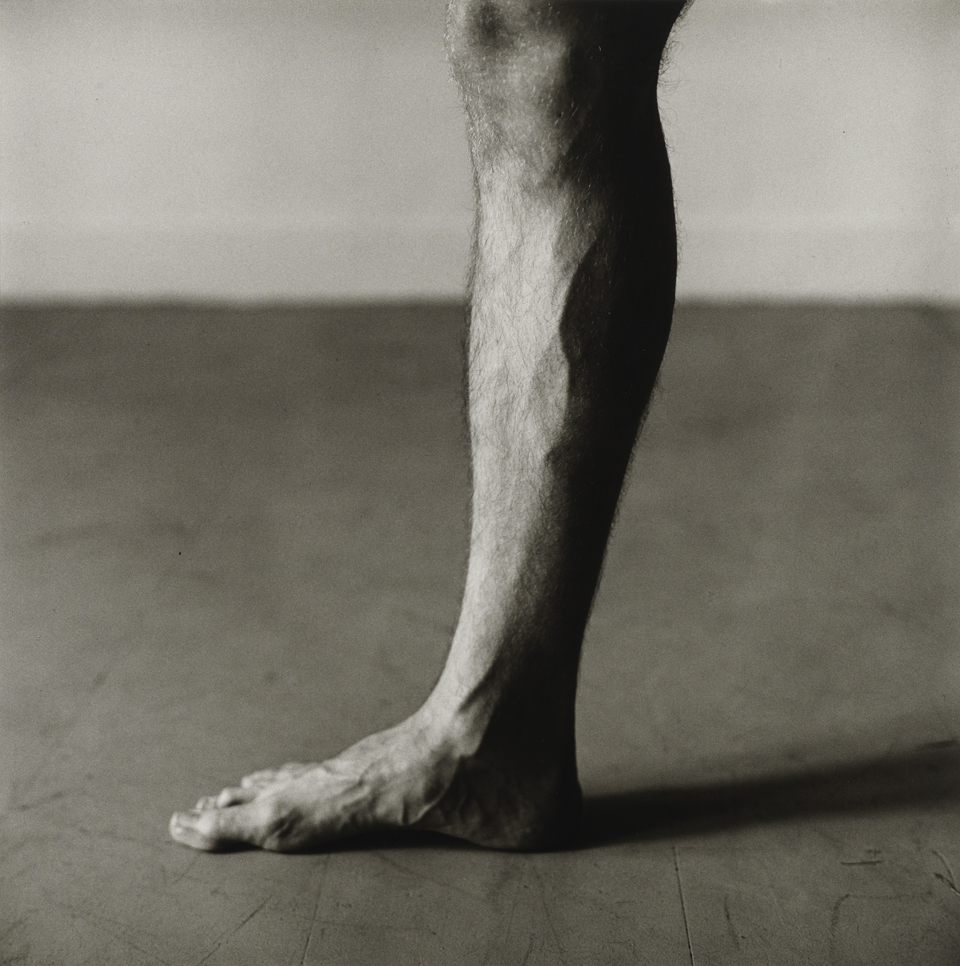

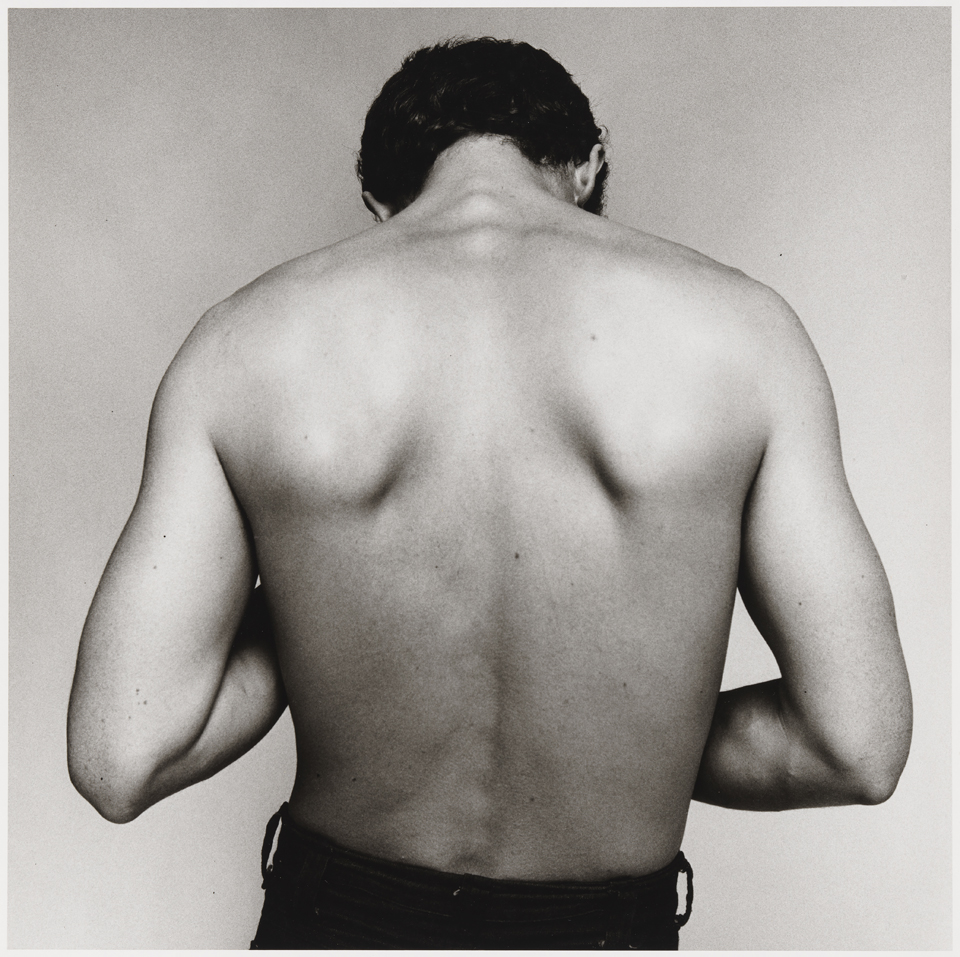

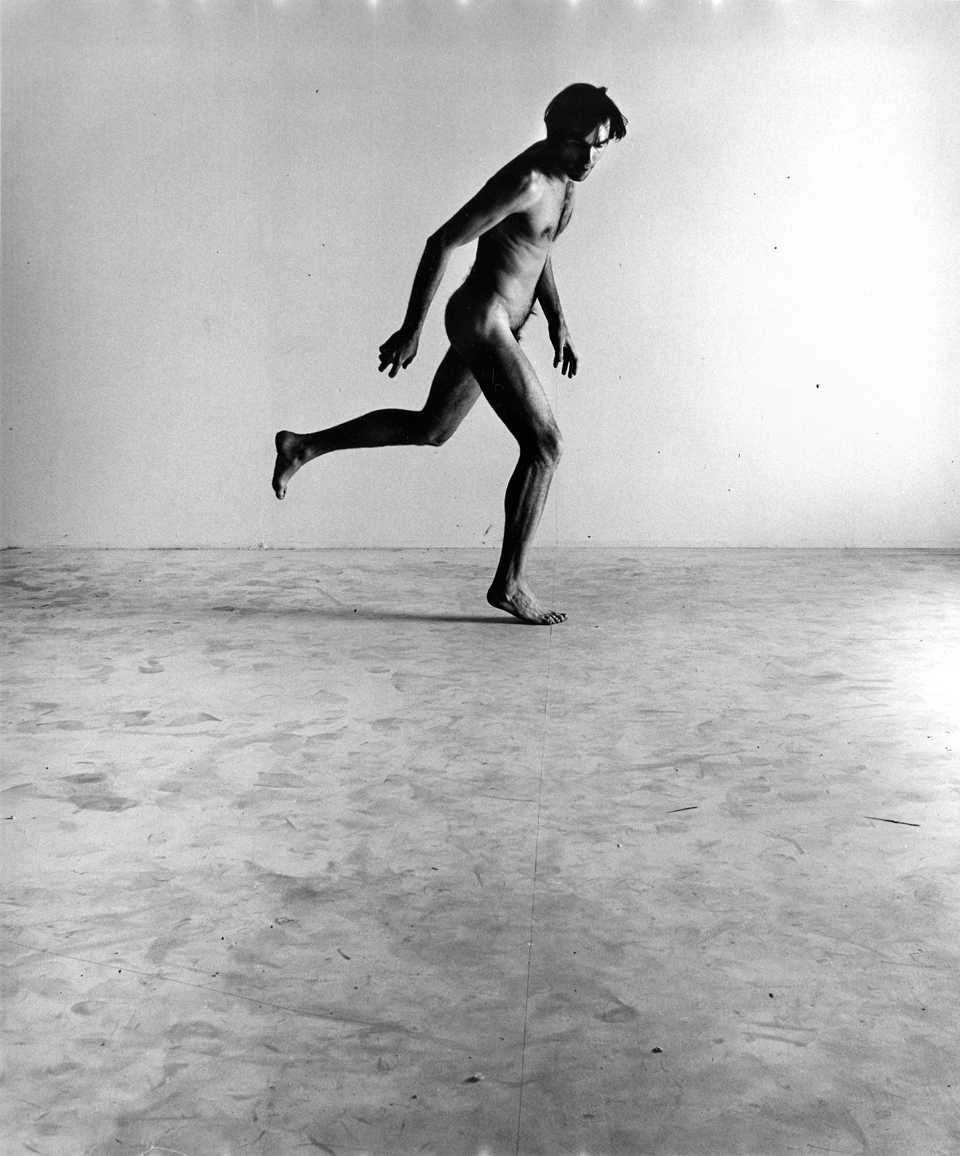

New York was his home: when Peter didn’t take portraits, he roamed the streets. He compared the city to a person and, taking photographs of naked men, tried to convey the character of the metropolis through poses of models, play with genitals, texture of bodies.

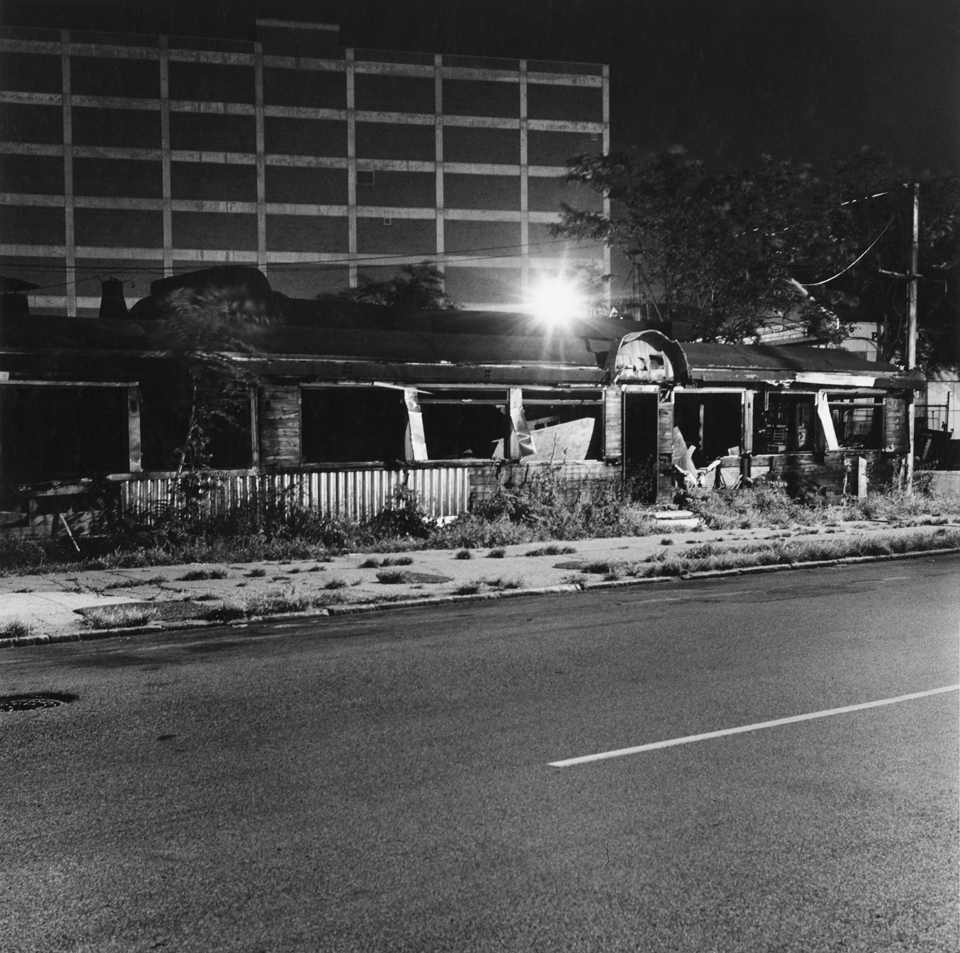

He loved the dark places of New York, adored dangerous drinking places for gangsters and pimps. He took friends around the lost corners of the city and enjoyed their fear. Writer Fran Lebowitz, a close friend of the photographer, recalls: “I went to extremely serious, very heavy S&M bars. West Side downtown there were these burnt-out piers. They were used by gay men to have sex in. They were pitch black inside … the environment was very rough and dangerous. Peter was physically fearless in the city, that’s for sure, when there were plenty of places that were dangerous to go in New York.” There, in the dark alleys, in the slums, in the God-forgotten quarters Hujar would often find inspiration, met the heroes of his photographs.

The photographer liked people who dared to do something, found courage, overcame something. All the characters that remained on film are always playing with something personal, intimate, carried some kind of an image in them from deep inside their beings. Leibovitz said that Peter was unlike all the other many photographers that she knew.

Despite a large number of friends and lovers, Hujar was a lonely man. He lived on edge, was always the center of attention, everybody loved him, and everybody wanted him. However, depressive states almost never left him. Younger photographers who came under the influence of Hujar made successful careers. Hujar envied Robert Mapplethorpe, but there was nothing that he could do.

In 1980, he met artist David Wojnarowicz in a bar — a broken and unstable man. Their relationship was complicated, uneven, and impulsive, but lasted for seven years — until Hujar’s death. David captured his loved one on his deathbed, when Peter developed pneumonia from AIDS. David knew that he was capturing his death, too: he would soon follow Hujar.

At the end, Peter said that now he would become famous: like many artists after death. And this was what happened — only after three decades.

At the end, Peter said that now he would become famous. And this was what happened.

New and best