Hero on Heroin: Life and Death of Davide Sorrenti

A fashionable photographer and chronicler of New York parties Davide Sorrenti came from Napoli to the USA in the 1980s at the age of five. His mother, Francesca Sorrenty, was a model, a photographer, and a stylist, and all of her children also grew up creative: son Mario became a fashion photographer, daughter Vanina — fashion photographer and stylist. All three were in such demand that in the 1990s the Sorrenti were dubbed the ‘Corleone family of fashion photography.’

Davide took the camera at 18 and immediately became famous — but he worked for a short time: at 21 he died from a kidney disease that was likely provoked by drug abuse. His biography became a diary of the entire ‘heroin chic’ epoch.

I, My Friends, and Heroin

There are many reasons why drugs became part of 1990s American culture. The main one probably was the increase of drug traffic that caused an incredible fall in prices on weed — to the point that it became available to primary school students. Some say that ‘heroin chic’ was a reaction to the false glamour of the 1980s, to an economic crisis and unemployment, and devaluation of the values of the previous generation, the boomers. One way or another, the society drowned in white powder, and people from show business immediately picked up on the junkie aesthetics promoting fashion on living high.

Grunge reigned music, and rock band leaders died of overdose in large numbers. The cinema also got hooked — let’s think Pulp Fiction or Trainspotting. Writers and artists, dancers and actors — together with them, workers and officials, policemen and military — all strata of American society were to some extent on hard drugs.

The fashion industry was not an exception: British photographer Corinne Day took photographs of the young Kate Moss as an exhausted beauty — almost painfully thin, pale, with dark circles under empty eyes. The photographer was immediately attacked by journalists — in particular, Amy Spindler, the one who introduced the term ‘heroin chic’, spoke against the propaganda of anorexia and drug addiction.

The journalist could hardly do anything, though: photography and fashion were only the metastases of the disease that affected the entire society. Corinne created a collective portrait of 1980s youths.

Keep Lying Like That

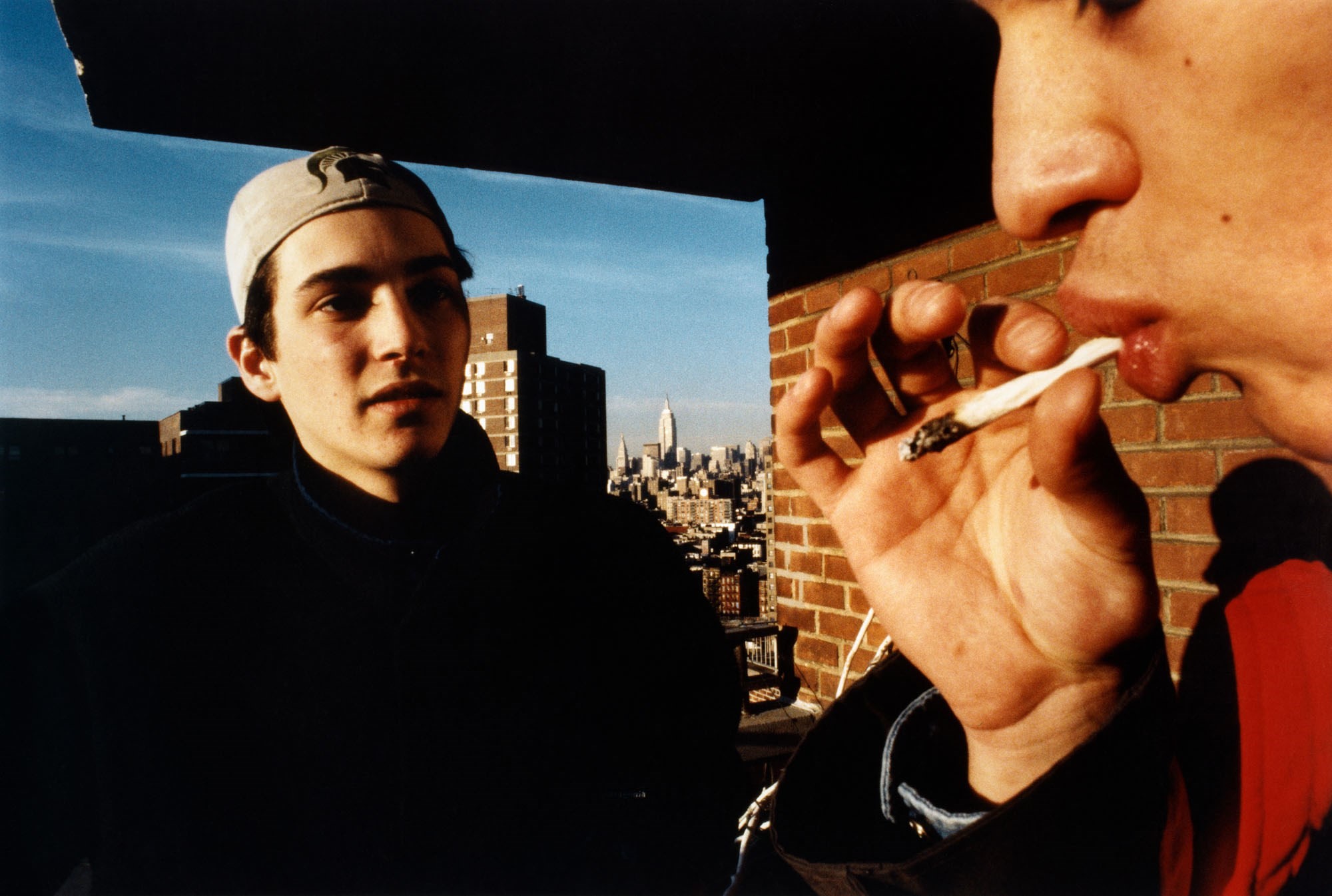

Davide immediately took to bohemian life — and the drugs that he started taking back when he was the leader of the school street crew called Some Kids Envy. Since 1994, he captured this group of reckless young people whose leisure was filled with marijuana smoke and heroin, skating and painting the walls. He then switched to fashion. Curator and model Berro recalls how she came to see Vanina in a jean jacket — Davide made her turn in inside out and photographed her like that. Everyone loved it.

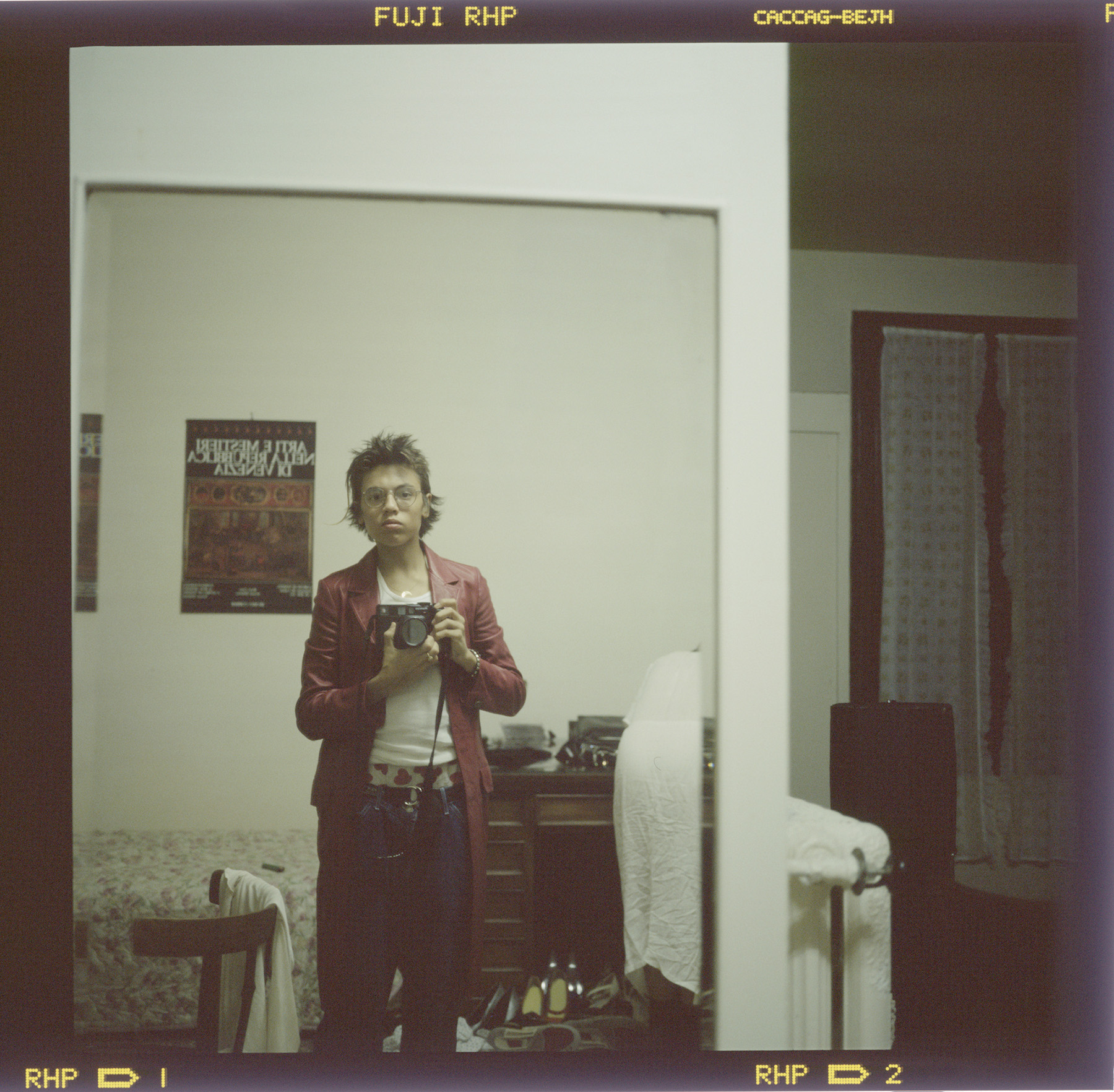

Sorrenti photographed hip hoppers, skaters, fans of grunge and rave cultures who crowded the streets and clubs to have fun, devoured by fashion, music, and movies. Everybody recalls how Leica M6 lay in Davide’s hand so naturally that nobody noticed it, and so people could be as sincere as possible next to him. His photographs turned out to be bright, expressive, filled with energy and beauty of youth — with a bit of drug aftertaste.

Seeing her son’s talent, Francesca loaded him with shoots for magazines — and he himself also went door to door to publications looking for work. Detour editor Long Nguyen later said about the day when Sorrenti turned up in his office with a thick notebook filled with pictures that it was like meeting someone not through words, not through wasted hours, but through a series of photographs and images that at first seemed random but were in fact reminiscent of the words of an autobiography.

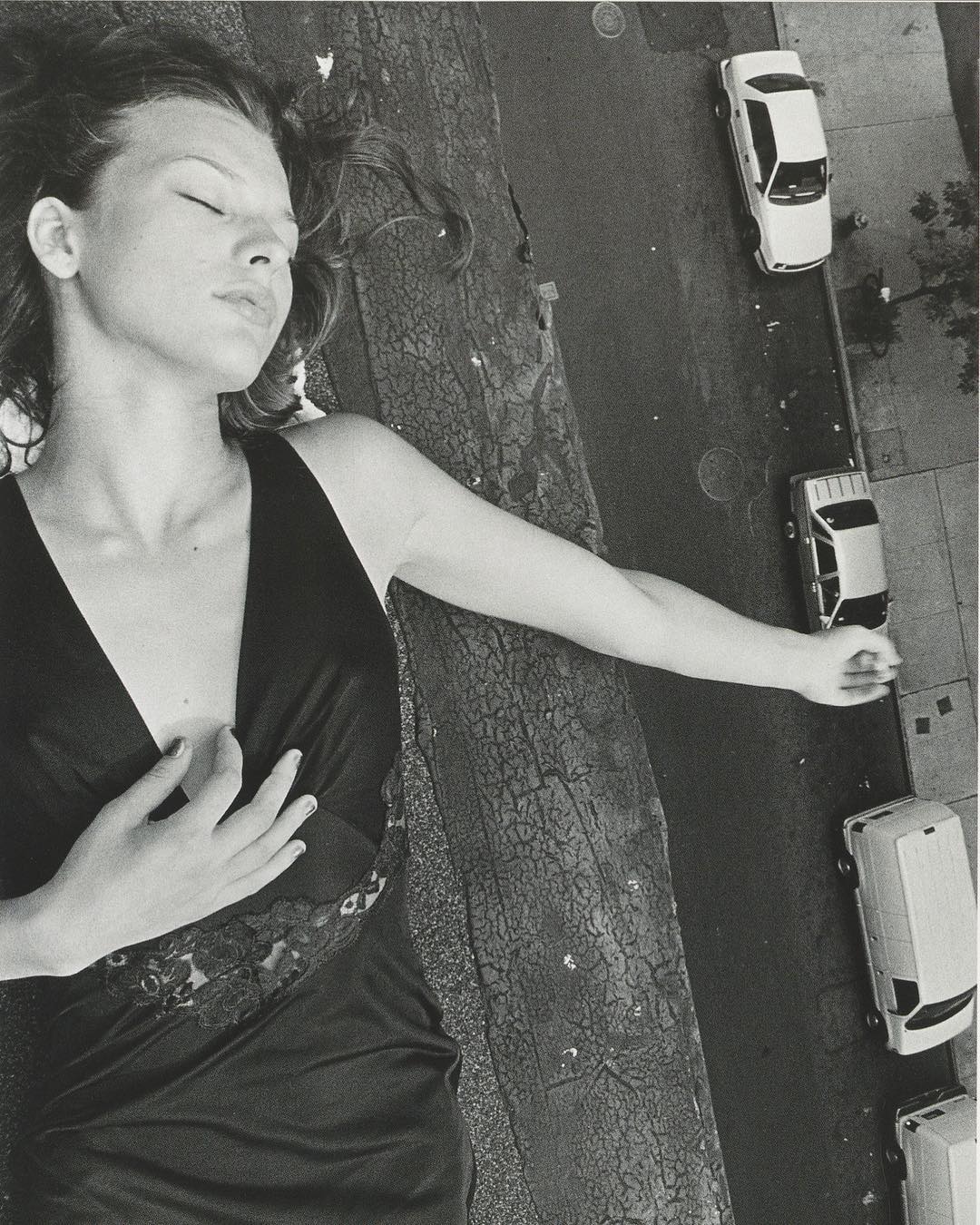

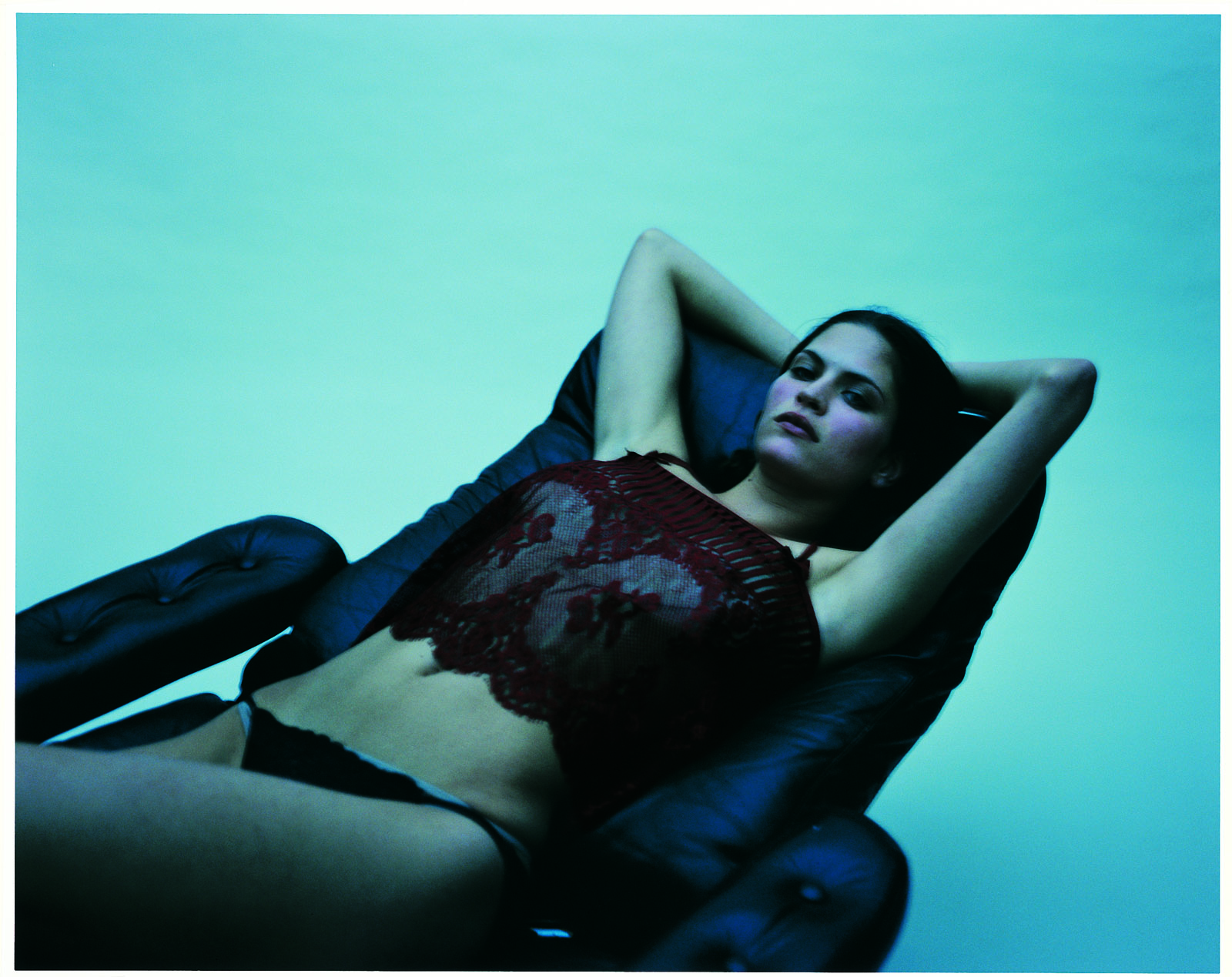

Davide captured emaciated models who could barely stand on their feet in uncomfortable and often awkward poses, dressed in expensive clothes from famous brands. The editors liked his slightly naive style that played on the girls always being hungover and lacking sleep, and the photographer kept getting new clients. His work was published by the largest glossy magazines about fashion: Interview, Detour, Surface, Ray Gun, and iD; he worked with Kate Moss, Mila Jovovich, and Jaime King.

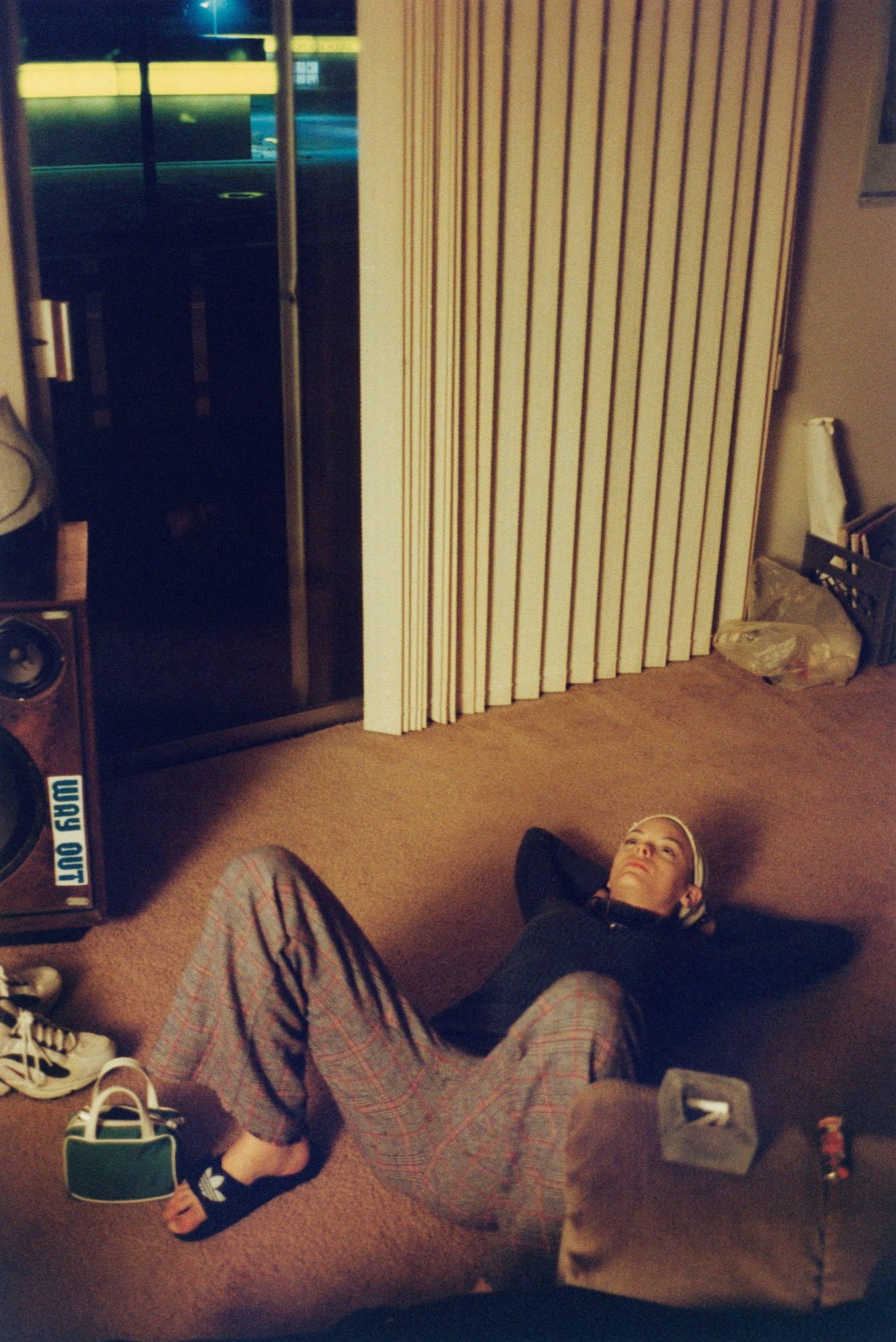

Jaime, who was also his girlfriend, turned out especially well in the pictures — she looked both romantic and horrible. In one of the most famous photographs she is unwashed in ripped clothes melancholically lying on the floor with her legs wide open surrounded by photographs of famous drug addicts on the wall — Sid Vicious, Kurt Cobain, and Jerry Garcia. King is still afraid to show this work — because it received so much criticism.

Fun and Done

Journalist and art critic Barbara Lippert wrote that in fashion magazines every sexual act, every tattoo or piercing is brought to the extreme, to death. We could say that was the way people lived in those times.

Davide captured emaciated models who could barely stand on their feet in uncomfortable and often awkward poses, dressed in expensive clothes from famous brands.

Jamie and Davide lived as if they were immortal. Jamie recalled that it was impossible to exist in any other way at the time: you needed to hit the bottom and then decide whether to stay there or to try to get out. It is weird that Sorrenti managed to turn 21 at this pace. When Davide died, King decided that it was time to move on — she quit drugs, became a successful actress and had a family. She remembers Davide as a dream, as an unquenched thirst.

The young photographer would spend the nights with needles and tubes that connected his body to the machine that pumped his blood. Thalassemia — a hereditary disease that prevents the normal production of hemoglobin — was ruthless to Davide. Mario took pictures of his brother in those hours knowing that the photographs would make history.

When Davide died, his mother launched a powerful campaign against ‘heroin chic.’ She was supported by President Clinton: “….the glorification of heroin is not creative, it’s destructive. It’s not beautiful; it’s ugly. And this is not about art; it’s about life and death.” Police increased control over drug trafficking, and they increased in price again. Journalists defended a healthy lifestyle. The popularity of grunge went down, fashion magazines switched to a different style. There was less glorification of high, and soon it was replaced by frank narcophobia.

However, this new turn played a cruel joke on Davide: after he died he was made into a scapegoat and accused of promoting drug use. There were many articles in the press that in detail described how the photographer died of drugs, but didn’t mention his horrible disease. When Davide’s mother and his friends tried to argue with them, they heard that Francesca Sorrenti had a reason to actively start speaking against ‘heroin chic’: she knew what really killed her son. It was decided to forget about Davide Sorrenti for a while.

However, people have been talking about him again in recent years. Some critics see the value of Davide’s photographs in contradicting aesthetics, some — in how he managed to beautifully tell the story of madness and the death of ‘heroin chic’, create the portrait of another lost generation. The third consider him a victim to circumstances — a handsome and very talented guy who thought that was how you were supposed to live your life — stay high and burn briefly, but brightly.

Sorrenti had two years in photography, but he managed to do more that some famous photographers managed to do in decades. Director Charlie Curran who filed See Know Evil about Sorrenti said that Davide celebrated life and calmly moved towards death, was fearless and tried to make art while he still could.

Photo: Davide Sorrenti Archive, IDEA Books

New and best