Donald Njatah Nya’s Black and White Life: A Cameroonian Fighter in Ukrainian Cherkasy

It is ten below zero. The ice-cold wind from the Dnipro River makes lifeguards crowd around the trailer with a heater and hot tea.

“Let’s not take pictures right after swimming!” — all sportsmen from the Grizzly Club, who came to Riviera beach for the traditional Epiphany bathing, laugh out loud. Even the girls, who don’t have to worry about shrinkage — but not Donald Njatah. He either doesn’t get the words, or the joke.

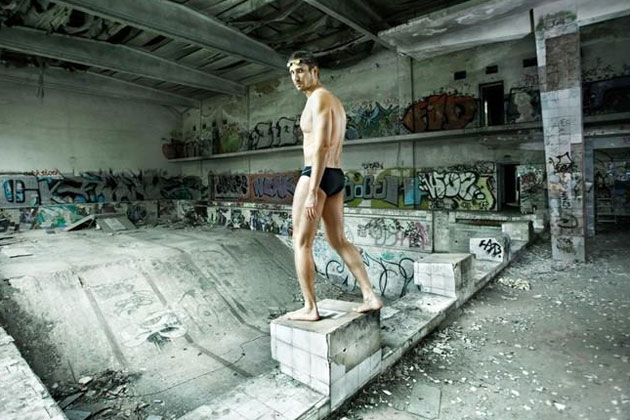

The changing room is set up in a large military tent. Njatah peeks out for a second, winces and disappears inside. It seems there will be no show. But soon he appears again with a towel around his neck, and runs to the ice hole. There is indeed no show though. The 95 kg Cameroonian athlete in his underwear on a frozen Dnipro River in Ukrainian Cherkasy attracts much less attention than you would expect him to. Only on the way back Donald is met by a crew from a local TV channel — as always, asking about his impressions.

“Good! Very super!” — he says in Russian with an accent.

They are used to it. Donald says that at first the finger-pointing and laughter behind his back were more excruciating than the cold. Now, five years after, the citizens don’t even turn their heads. Njatah’s two main wins are knocking Jeff Monson out and assimilating in Cherkasy.

Jeff ‘Snowman’ Monson was never the first in MMA, but has always been considered a good fighter. 36 of his 58 wins in tournaments were by submission. Monson broke many outstanding athletes — Sergei Kharitonov, Kazuyuki Fujita, Mark Kerr, Roy Nelson, and Alexander Emelianenko.

At the end of the previous year, a 44-year-old American took Russian citizenship (which, of course, has prompted many jokes about him being the Gerard Depardieu of martial arts).

Donald Njatah was brought to Moscow to get slaughtered. He makes a good show in the ring, but has had four losses in 2015; he is neither Russian nor from the Caucasian mountains, which makes it easier for a MMA audience in Russia to support his opponent in the ring; he is not a wrestler. The first fight under the Russian tricolored flag was supposed to end for Monson with a sure and ideologically correct win. Monson entered the ring in a Vladimir Putin T-shirt. And then, during the first 20 seconds of the fight, the former American citizen received a lowkick and two proper jabs and lost his mouthguard.

“Only working with his legs, only keeping his distance and short attacks like this one can save Donald Njatah Nya. For this, he needs to feel the distance, he needs stamina. Let’s see if he has those…” — The Match TV commentator didn’t finish his sentence. Njatah made his first and last right punch in this fight. Jeff Monson fell on the floor face first. Slava Vasylenko, Donald’s trainer and manager, unfolded a blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flag.

Wins and Losses

“You’ll recognize Donald at once. And a small guy by his side would be me” — We are making an appointment to meet Slava Vasylenko. In 2010, Slava won the Combat Sambo World Championship in the weight category up to 62 kg and started the Grizzly Club. The name came to him in a dream.

“I had a dream to have an African guy training in my club. I saw videos from America: everyone is white, and then there are one or two black fighters. This is so cool: when you have the Azeri guys, the Georgian guys all training together”, — Vasylenko explains. He saw a photograph of a student of Cherkasy State Technological University, Donald Njatah, standing in his kimono on the Russian social network site Vkontakte. At the time, Donald had recently moved from Kharkiv to study to be an electrical engineer, as the teaching in Kharkiv was in Ukrainian, a language he at that point had no understanding of at all.

The young man had experience in karate, as well as impressive speed and strength of punch.

Baghante and Tongan are the languages of his parents. French and English are the state languages of Cameroon. By Ukrainian standards, Donald is a polyglot, but he is having trouble with Slavic pronunciation. During our conversation he is silent a lot, and is busy trying to mend the broken zipper on his backpack with a toothpick. It’s Vasylenko who does the talking.

When the opponents assessed the skills of the Cameroonian, it became difficult to organize fights for him in Ukraine. The war in the east of the country and economic crisis made things worse. Oplot in Kharkiv, the only MMA club in Ukraine where the athletes were on a monthly wage of $500, stopped operating. The number of commercial tournaments rapidly decreased, and the monetary prizes became very nominal. In 2014, Njatah fought in Ukraine only once, and the next year he had to face more experienced fighters in Russia.

“They always meet you with expensive cars, bring you to a hotel, always feed you, and never say a word about relations between Ukraine and Russia…” — Vasylenko says.

Donald’s four losses the previous year — by technical knockout and by submission to armbar and rear-naked choke — must have made Monson’s team enthusiastic. Now his manager is dreaming about a rematch with Monson, a fight with Fedor Emelianenko, and a transfer to the American UFC. Meanwhile, Donald trains amateurs. A month subscription costs 250 UAH ($10), and this money is his salary.

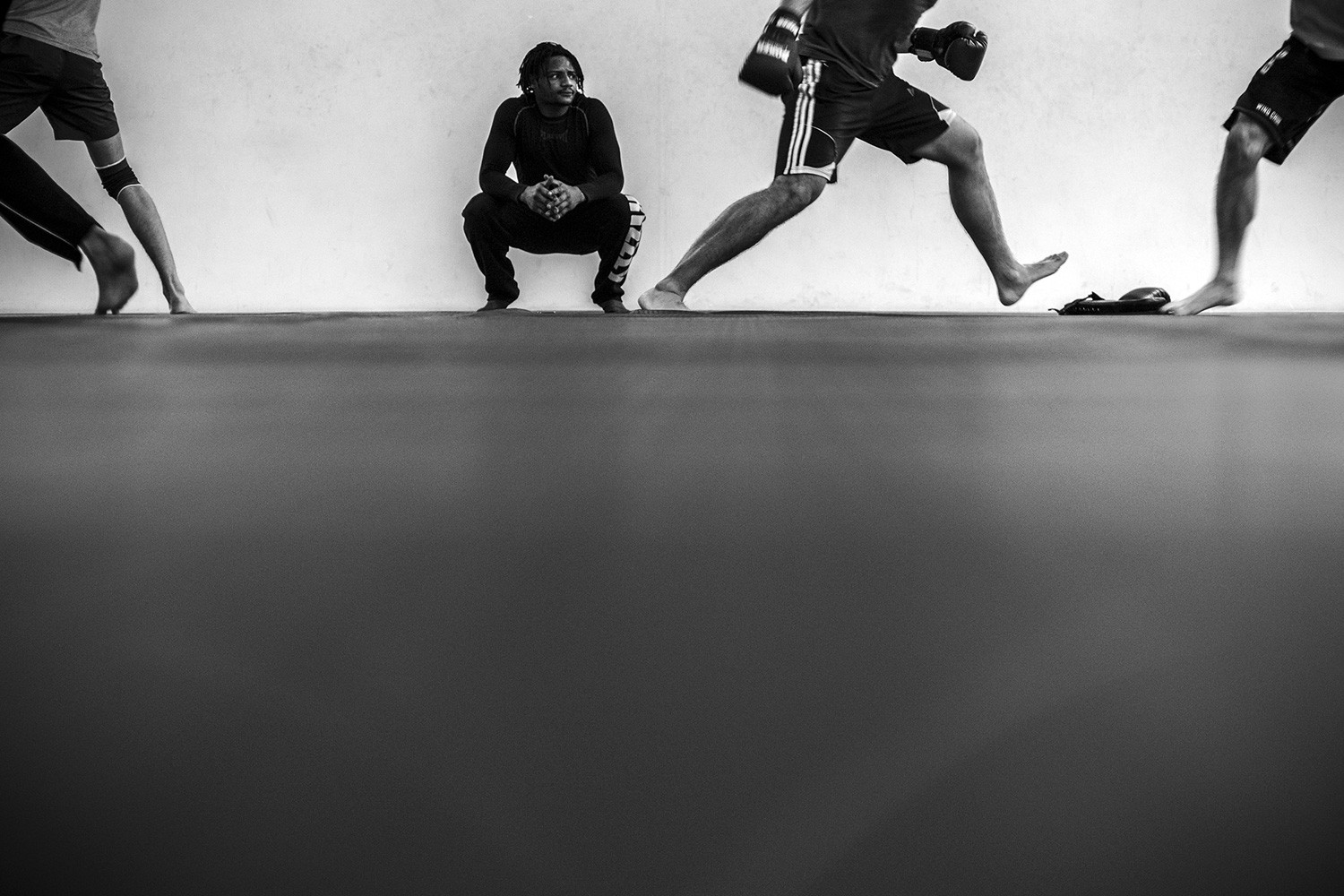

Usually, about 20 people come to train with Njatah, but this is the first workout after the holidays, and there are only six of them in the gym. Three of them are talking in a different language and perform better than the others.

“Uzbeki… Turkmeni… stan.” — the trainer isn’t sure.

After a short warm-up the young men start working in pairs. Donald teaches them to fight the way he fights: quickly approaching to punch, and even faster retreating to avoid the counterattack. The most important things are working with the legs and choosing the right distance. Njatah shows the right position in front of the opponent, and the move, and makes the guys repeat. “I am here. Ok? Let’s go!” — in the course of a couple hours this repeats fifty times. Leg takedowns, back attacks, high kicks, series of punches. “40 push-ups!” — if you didn’t listen carefully.

Donald Njatah and Yulia Tymoshenko

We meet Yulia Tymoshenko in the church, where Donald’s friend, also from Cameroon, is baptizing his baby. Yulia, who has the same name as the former prime-minister of Ukraine, is Njatah’s blue-eyed wife with delicate features. She did not change her last name after they got married. Yulia comes with the couple’s daughter, Eva Kristina. Donald carries the child in his arms, gives her many kisses and baby-talks to her in French.

— Are you Catholic? — I ask Donald.

— I am Protestant. — He replies.

— But you’re Orthodox! — His wife intervenes.

Donald ends the short argument about terms by saying: “I believe in God!”. Cameroonians cross themselves discordantly. The priest turns his gaze away.

Yulia is 24, her husband is a year younger. They met in the dorm of Cherkasy Tech, where two floors are occupied by foreign students: Africans, Chinese, Arabs, and Russians.

Donald is on an academic leave, Yulia is a chemical engineer with an honors diploma, which she received when she was 9 months pregnant. The two main production facilities in Cherkasy are a mineral fertilizers factory and a pharmaceutical factory. The young woman has not yet decided whether she wants to work there after her maternity leave. A production engineer’s salary of 4,000 UAH ($160) is considered high by Cherkasy standards.

In a cafe Njatah orders a large pizza and a ‘Georgian pan’ with potatoes and meat. He winces — the food is not good. He cooks national dishes himself, when his mother sends him ingredients from Cameroon. She keeps a close eye on the youngest of her five children, and makes a Skype call to Cherkasy every day.

This summer Donald will take Yulia to Yaounde to meet his family. Her relatives he already knows very well. The way he pronounces ‘grandma’ and his homemade Ukrainian varenyky dumplings melt her village grandma’s heart. His father-in-law worries about his son-in-law a lot, and watches only recordings of his fights, when he already knows that Donald did not have any serious injuries. This is not always the case, and after every tournament Donald checks himself in to the hospital.

“After the fight, I go to the toilet. I have blood everywhere, I piss blood. I think: Why did we fight? We have no problem between us! I don’t know him, he doesn’t know me, why did we start fighting?! I look at my bloodied face and think: I earn my living for a whole year with this fighting!” — with dread and nostalgia, Donald reminisces about Kolizei (Coliseum) tournament in Kyiv. There, if you won four fights a night, you could get not only injuries, but also a prize of $4,000. The economic crisis has almost destroyed MMA as sport in Ukraine, and now fighters get paid between 2,000 and 4,000 UAH for winning a tournament.

Njatah’s big dream is a rematch with Monson in Cameroon. His big problem is that his last win is not yet included in the official statistics on the main MMA website sherdog.com. The organizers of the Moscow tournament are endlessly procrastinating with sending the information, and his profile remains unchanged since last year.

DONALD NJATAH NYA

YAOUNDE, CAMEROON

AGE: 23

CLASS: LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT

HEIGHT 182.88 CM

WEIGHT 92.99 KG

WINS: 13

LOSSES: 6