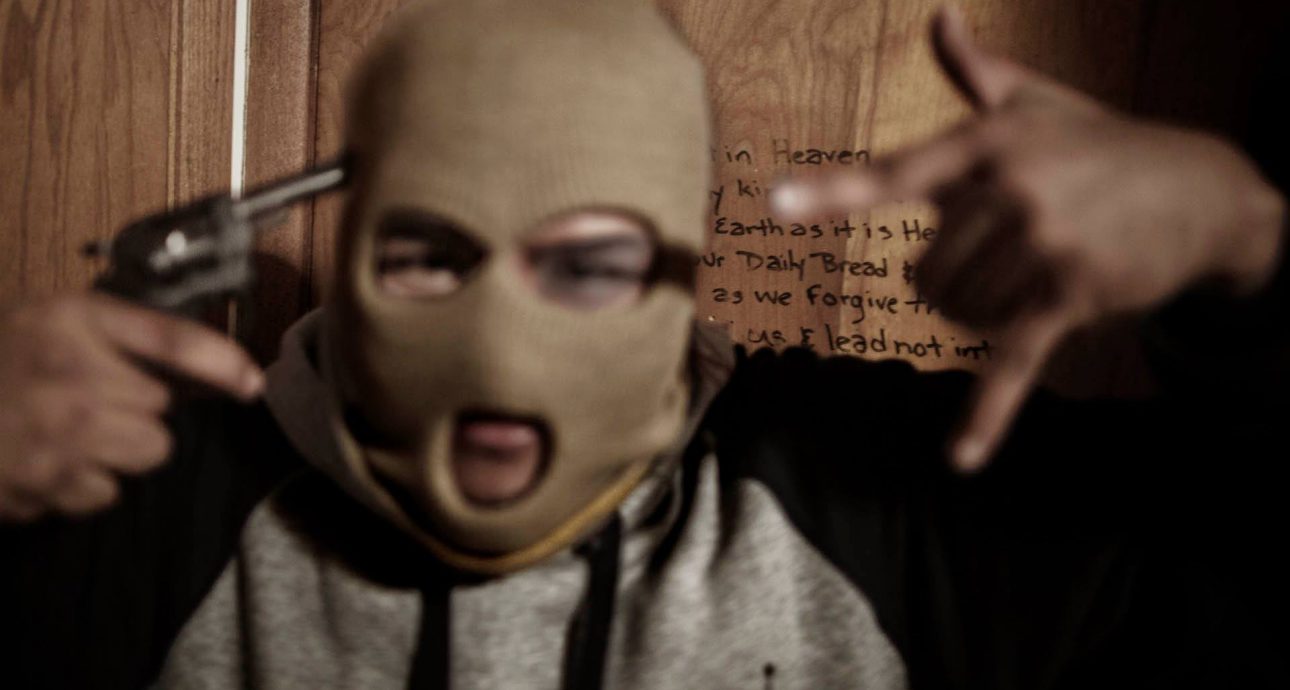

Espen Rasmussen Presents Hard.Land: A Project on the American Dream Failing to Materialize

Norway photographer and photo editor. Winner of two World Press Photo awards, won POYi several times (Pictures of the Year International). Is on the list of 30 emerging photographers by Photo District News. In 2007, Espen received a $60,000 grant for shooting a project about refugees all over the world, which resulted in Transit book published in 2011. Works for Panos Pictures agency. Works for The New York Times, The Independent, Intelligent Life, Fader magazine, MSF, NRC, and UNHCR. Published his works in Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, Der Spiegel, and The Economist magazines, and in The Guardian, The Sunday Telegraph, and The New York Times newspapers.

Not Only Dreams

I was at the screening and saw your Hard.Land and it reminds me of one movie that was released in Russia. It’s called Leviathan, and it’s not the same, it’s about fighting against the system, but there’s a theme about the poorest regions in Russia. After it was released, the director received a lot of criticism: “Why didn’t you make a movie about good things? Why did you want to show Russia in a bad way?” Did you hear something like this about your project?

Yes, I did. Not a lot, but I’ve shown the project at different festivals, and Americans reacted more than Norwegians or other audiences, they said — “why did you just focus on the sad things and hard things? Why don’t you see all the good things that are going on in the US?” I was like — you might be right, but at the same time, that’s where I actually choose to go, because I think it’s important to document that.

I end up with lot of stories about drug addicts, miners losing their jobs, people living in the ruins in Detroit, and people earning maybe seven dollars an hour, after having two or three jobs every day. I think those things are important to tell you. You have an idea of the US being the place in the world where everything is possible, and the American dream, but when you go there and you go outside the big cities you realise that there’s a lot of broken dreams also. So that was what I wanted to focus on. And at the same time, there are also other stories within the project which are also very positive. I mean I have that as well. It is not only the sad things. So I don’t feel it’s fair to criticise.

Preview of Hard.Land project

How did the idea of this project come to you?

I’ve done this together with a reporter, and he used to be a correspondent in the US for a Norwegian newspaper, so he had traveled a lot in this region and knew a lot about the problems in the US. He suggested that I go there and spend a couple of weeks, and it turned into a project.

How much time did you spend there?

Not that long. Maybe twelve weeks in total over a period for almost two years.

How did you find heroes and why did they agree to be shot?

It’s very easy. In the US, people are very OK with being photographed, they love being in the media. And at the same time I’m Norwegian, and that kind of makes it easier because a lot of Americans love Norwegians because they’re like: “Oh, my grandfather is from Norway! He emigrated in 1954” And they always think that they have some kind of relationship. And then, I spent a lot of time with them, and then they gave me access.

Do you usually make friends with people you photograph?

Not like friends friends, but I get to know them, they trust me and then give me access. And then after, I send them pictures and we’re friends on Facebook. I have pictures of the couple in bed, these pictures were not shown here, they were having sex you know. And people always ask — how did you manage to take a picture of them having sex? And it’s very easy you know, because we were hanging out and smoking weed, and then they just started, and I was in the bedroom together with another guy, we were chatting. They were having fun in bed and I took my pictures. And then I showed them a picture, and the girl was like: “Very nice, it’s the best picture of me, send me some!” I sent her maybe two hundred pictures, so she’s got everything documented now.

Normal Life

You have a lot of projects full of pain. Are you a sad person yourself?

I think I tend to focus on not a happy side of the world, but you know, I have three small kids, we live in a house outside of Oslo. I’m happy. I choose things that could engage me, activate my brain in different ways, I need to be really in the story, I can’t just go and do a story and then leave, you know. I like to go out and really get involved in something and work on it for a long time.

Can you have a ‘normal’ life when you choose the profession of a photojournalist? It’s not that easy, right?

It depends on what you choose to do. In my case, I travel a lot and that’s very hard for the family. In Norway women are equal to men, they have equal rights to work and everything, but of course because I’m away so much, my partner has to do a lot of work with the kids, the school, sports, everything they are involved in. She has to take on a lot of the burden, so it’s not a perfect job for a family. But you know I saw a lot of photographers get kids and choose to just scale down for some years, be with the family, and then when the kids are getting older they are starting working again, and others stay and work on domestic projects, in Norway there are many good photographers who don’t travel, they work on stories inside Norway. It depends on what you choose to work on.

When I see pictures by you, I definitely know it’s your pictures. They are kind of cold, they give me a feeling of coldness. Did you hear something like this about your work before? Does it come from the fact that you are from Norway or what is the reason?

That is a good question. People say they can see it’s my pictures. They don’t really describe it, like you do it, they describe it as a style more, than a feeling. But I’m more happy to hear that you get the feeling and not just see the style! It was not my intention to make the pictures cold, but I think it also depends on the people who see it — you get that feeling, others will get a different feeling, and that’s what great about photography.

What do you like more, when it’s hot or when it’s cold?

When it’s hot.

Is that why you live in Norway?

It’s true that in Norway you have one and a half months of summer, the rest is bad weather, and it’s cold. I don’t like winter anymore, I loved it before, because I do a lot of skiing. But now I would prefer longer summers.

Everything Else But Me

What was your best trip?

It’s very difficult for me to pick one trip because it’s about the whole project. For Transit, I went to twelve or thirteen different countries, and I think that is by far the most important thing I did. I personally managed to get the message to a lot of people, and I think that’s important. I photographed a lot of refugees and displaced people and I still do. I worked on that for ten years, my head was only with those people. Last year, I worked three or four months following two brothers traveling to Europe from Syria. Every year I go back and work on refugees and displacement.

Maybe you can choose the worst trip if you cannot choose the best trip?

Maybe the worst living conditions were in Tchad in 2004. I lived in a desert, it was like 55 degrees Celsius, very dry, you get burned just by walking outside, and the water was almost boiling because of the sun. It was kind of surviving. It was kind of dangerous also because at the border with Darfur there were a lot of rebellions going on along the border, and we had to go by car and finally we got to the capital Geneina. And then I came to a hotel for the first time in ten days or something, and I just ran outside to the pool, and I swam, and then I laid down on the bed and I fell asleep in the sun, and when I woke up, my skin was boiling, and I was totally burned. And I had this big backpack I had to bring in the plane, and everything started to bleed, and there were open wounds everywhere, so that was hard.

What is more difficult to you emotionally — to work as a photojournalist or to work as a photo editor?

I think as a photographer, because as the editor you see work, but you don’t really meet those people who are in the pictures.

What is the main aim to be a photojournalist for you? Have you found it?

No, but I think one of the key things is to be curious about other people’s lives, about other countries, about other religions — everything else but me, you know.

Do you feel ashamed for something that you did in your career as a photojournalist?

No, I think actually I behaved very well. I have quite strong ethics when I meet people, and that’s because I know that as a photographer I also have responsibilities, especially today, because everything ends up online. I go to a country, and I take pictures and they might see it, you know, or their friends might see it. I never step on dead bodies to get my picture, you know. I try to behave. Like with one of the stories with the refugees, the first time I went there was nobody there, and the last time it was like a hundred photographers, and then I just backed off. I’m not very fond of being too much of a photographer. And if people say “no, don’t take picture”, I don’t do it.

What would you never shoot?

I don’t know. It’s hard to say before you see it, but there’s a sense you have when you’re there, and the thing is in front of you. But most things you should take pictures of. Because it’s not about if you shoot it, it’s about if you publish it.

New and best