System of Absurdity:

What Soviet Bunkers Looked Like

Photographer, member of MAP6 collective. Works on documentary projects where he studies the identity of post-Soviet countries that joined the EU. Had solo and group exhibitions in Britain, Italy, and Russia. Worked with the BBC, Calvert Journal, View Magazine.

— In October 2015 I visited Lithuania as part of the MAP6 Collective, as part of a collective project to explore the shifting concept of what defines modern Europe. In particular we wanted to visit the country that was, at the time of our visit, recognised as the ‘official’ center of Europe.

During the 20th century there were two dominant political and military forces that shaped and misshaped the country. The first was the invasion and subsequent atrocities of the Nazi Germany regime, and the second was the long Soviet Occupation which followed this. For this particular project I was interested in exploring the impact of the Soviet Occupation on the country between 1944 and 1991.

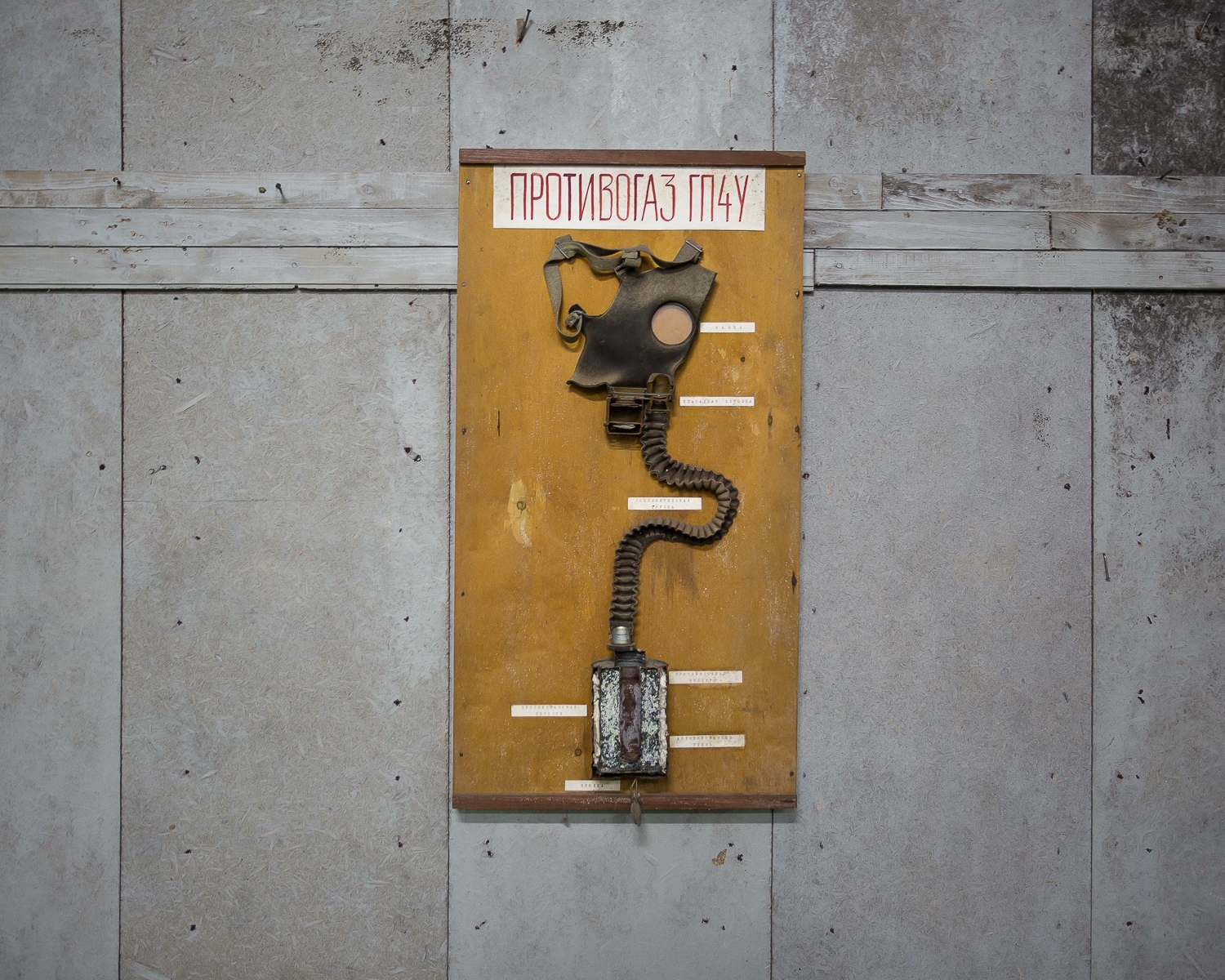

The Soviet Bunker is a staged environment, a fabricated space constructed from the leftover paraphernalia of the Soviet Occupation just outside the city of Nemencine. It is set within a former Soviet telecommunications center, one of many such back-up stations designed to keep broadcasting in the eventuality of a nuclear war, part of the Cold War stand-off. It was built between 1983 to 1985 and abandoned in 1991. When the Russians left Lithuania they stripped the space clear, leaving the bare concrete cells of an extensive bunker. It is three meters deep underground, surrounded by thick forest. The bunker would have had it’s own water supply, bored directly out of the ground, and a heating and cooling system. Air was pumped in and out and two huge generators produced power. It would have been possible to barricade oneself in and survive on rations for months.

The bunker covers a square grid of 2500 m2. It has been adapted by its organiser, Mindaugas, into a place of theater, the rooms filled with salvaged Soviet paraphernalia from local markets.

Each room is meticulously arranged. Random doors open up onto a bewildering array of set designs, like scenes from low cost Doctor Who episodes: the red room with gleaming white bust of Lenin, table laid out with photographs of the Central Committee and map of the world on the wall where there are no separate Baltic States just one grey blue mass of the Soviet Union; the room with gas masks laid out on display on trestle tables; the interrogation room; the medical room with gynaecological chair and forceps; the Soviet shop with authentic Soviet products including a can of drinking water; and the faithfully recreated Soviet apartment, complete with a TV set, a laid out tea table, children’s toys and china figurines. Within this set space is the re-enactment: an actor is employed to issue out a torrent of abuse at the audience. It is a one man tour de force, a piece of absurdist theater designed to highlight the absurdity of real events. It’s purpose is educational; colleges send students here to learn from the experience. Afterwards the actor, in full KGB uniform, asks the audience whether they like their freedom — the implicit message being that the absurdities and horrors of the past need to be remembered so as not to be repeated.

This is a staged reality, a created fiction to highlight the absurdity of real events. The effect is eery: the uncanny reality of the Soviet regime enhanced by the subterranean and claustrophobic environment. These intricately set pieces occupy an interstice between the abandoned and the occupied, the past and the present, fiction and reality, fear and trauma.

New and best