Webcam Girls

Much of our communication is shifting to Zoom or Facetime, and relationships are increasingly becoming remote. Webcam models can be called experts in the field of sexual intimacy on the Internet: they communicate with their clients in video chats, undress on camera and embody their fantasies for money. In Ukraine, webcam modeling is illegal.

Ira Lupu explores in her project how intimate and authentic communication through a webcam can be. She wonders how online relationships affect a person’s self-esteem and perception of real life, and she tries to figure out who we all become when exchanging emotions through the keyboard.

Photographer, multimedia artist, and art director born in Odessa and based in New York. Her works got published in The New York Times, Vogue Italy, Dazed, i-D, Vice, InStyle. A graduate of the New Media Narratives program at The International Center of Photography (New York) and the Victor Marushchenko School of Photography, she participated in exhibitions at Dallas Contemporary, Tbilisi Photography & Multimedia Museum, and the Mystetskyi Arsenal. She received grants and awards from Women Photograph, Prince Claus Fund, Shevchenko Scientific Society NYC, and B&H Photo Video.

— Since 2016, I frequently went to Nikolaev, where I photographed the fashion model Yulia Poleva at her house. That’s how I got interested in characters who had a professional relationship with the camera. This, by the way, is considered the worst scenario for a conventionally documentary project: when the hero deliberately adds performativity, showing a kind of dual identity. But I like it.

In the spring of 2019, Marina Minimaus found me through friends – she worked as a webcam model, but she recorded a music album, and she needed to get pictured for a promo. Marina came up with a shooting scenario – a sad webcam girl in a cluttered apartment. I was impressed by her hypersensitivity and straightforwardness, the way she fearlessly opened up, not at all embarrassed by her profession (sex workers get shamed and judged everywhere, and in Ukraine – even more so). Her story has greatly influenced the overall spirit of my project ‘On Dreams and Screens.’

I soon left for America and began to think about the final project’s topic already at the beginning of my studies. At that moment, the story of Trump’s impeachment and his infamous phone call to Zelensky was thundering, so the fact that I was from Ukraine aroused everyone’s interest. I did not expect any deep awareness of what is happening in the country, but it became clear that there is none at all. Therefore, I decided to do a project on a topic related to Ukraine.

Many of the teachers at my school praised Teju Cole; it was infuriating because he was the head of the jury that awarded the Foam Paul Huf Award to the project I hated: ‘Ekaterina’ of Romain Mader. I did not understand how a critic, who writes so much and passionately about the predatory distortion of identities in photography, could fail to notice this in ‘Ekaterina.’ I came to the conclusion that the Eastern European woman is one of the most misunderstood phenomena in the Western world and one of the most exploited. I wanted to protect these women somehow, so I decided to take an almost stereotypical image and complicate it.

Eastern European woman is one of the most misunderstood phenomena in the Western world and one of the most exploited.

I had many ideas about Ukrainian immigrants in New York, and the topic of webcam models was not my top priority. But when I went on a winter vacation to Ukraine, suddenly, several girls associated with the webcam materialized. Two of them, Anya and Tasha, stayed with me for a long time.

First meeting with Marina. Odessa, 2019

Marina poses at home. Odessa, 2020

Anya on the tram. Pushcha-Vodytsya, Kyiv, 2019

During the whole time of working on the project, I was surprised mainly by two things. In Ukraine, where webcam modeling is formally illegal, there are many underground studios – models work there when they have nowhere to stream or are not yet able to withdraw money from abroad themselves. Such studios, as a rule, are covered by the police. The owners take up to 70% of the income and often blackmail the models threatening to send their inappropriate images to school authorities or family. And they often do so.

The second time I was surprised when there was a peak of COVID horror in the USA, and I lived on a farm cut off from the world in Upstate New York. Back then, I watched occasional Chaturbate streams. There I came across a group of entirely ordinary Slavic guys who often went online and did anything for money. But they got outraged if the audience asked if they were gay.

On Chaturbate I came across a group of entirely ordinary Slavic guys who often went online and did anything for money.

Nothing else in the structure of the webcam industry shocked me or amazed me. You can read themed telegram channels, spend a day streaming – and there will be no mysteries left. There are plenty of “informative” projects about this topic. I was interested in something deeper and more authentic. What exactly – I tried to understand.

In America, art studies are structured in such a way that 90% of the time, you and your mentors and classmates discuss every little thing, every nuance of your works and ideas. In these deep “psychotherapy sessions,” I found that I was unlikely to say anything new if I simply took a picture of a girl at work and that my interest in the topic stems from my own vast experience of virtual life, including long-distance relationships.

Anya in the places of her childhood. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

Anya in the places of her childhood. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

Anya in the places of her childhood. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

Anya in the places of her childhood. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

Anya in the places of her childhood. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

A still life painting in a sauna. Sasovka, Transcarpathia, 2020

When I put in the effort to find models (for example, I put paid ads in the Brighton Beach ad chat), nothing worked. The best heroines have materialized by themselves. I honestly said: “I am doing this kind of a project; we can work in any convenient format. We can take pictures, with or without a face, shoot a video, record a conversation. The main thing is your interest and readiness to participate.” Some of the girls don’t understand why I keep asking their opinion again and again: “These are your works,” they say. But I know that even the most professional and noble photographers sometimes act rather soullessly towards the heroes of their photographs. And I don’t want that.

It was a difficult project from an ethical point of view, and there were some mistakes on my part. One of the first heroines had an unpleasant story; I had to show more foresight. After that, I began to take on more responsibility, discuss and ask more questions. And even remove approved photographs or entire stories on my initiative.

I didn’t try to stream myself just because engaging in such earnings would put at risk my U.S. visa. But I got immersed in the project to the maximum depth. At the end of the school year, I even took a performance class, where I reincarnated as random web models I saw on websites. I can say that I even spent too much time with all the participants of the project. We traveled together, watched stupid shows, overate, got angry, and so on. I still communicate frequently with several members of the “main team.” They are very empathetic and creative people.

I didn’t try to stream myself just because engaging in such earnings would put at risk my U.S. visa.

The project turned out to be more about souls than bodies. About that slightly altered state of consciousness after an online marathon, a fantasy world resulting from a large amount of disembodied communication. It is also about a real person hiding behind a virtual body, real feelings, and even ordinary human relationships, albeit on a commercial basis. About injuries and dreams; strength and vulnerability.

Like any lens-based material, this photo project is interpretive to a certain extent, built on my experience of close communication with a limited circle of girls. I have no ambitions to draw conclusions about webcam modeling in general. At the ICP school, I studied new media, so ‘On Dreams and Screens’ has many manifestations – videos, interviews, performances, an interactive website, and an AR application.

Anya. Pushcha-Vodytsya, Kyiv, 2019

The pillow Alex took a selfie with. Washington, 2020

Marina is photographed for the album cover. She came up with the image herself. Odessa, 2019

Dasha on the salty bank of the Kuyalnitsky estuary, her favorite place in Odessa. 2020

Irina's stripper shoes. Odessa, 2020

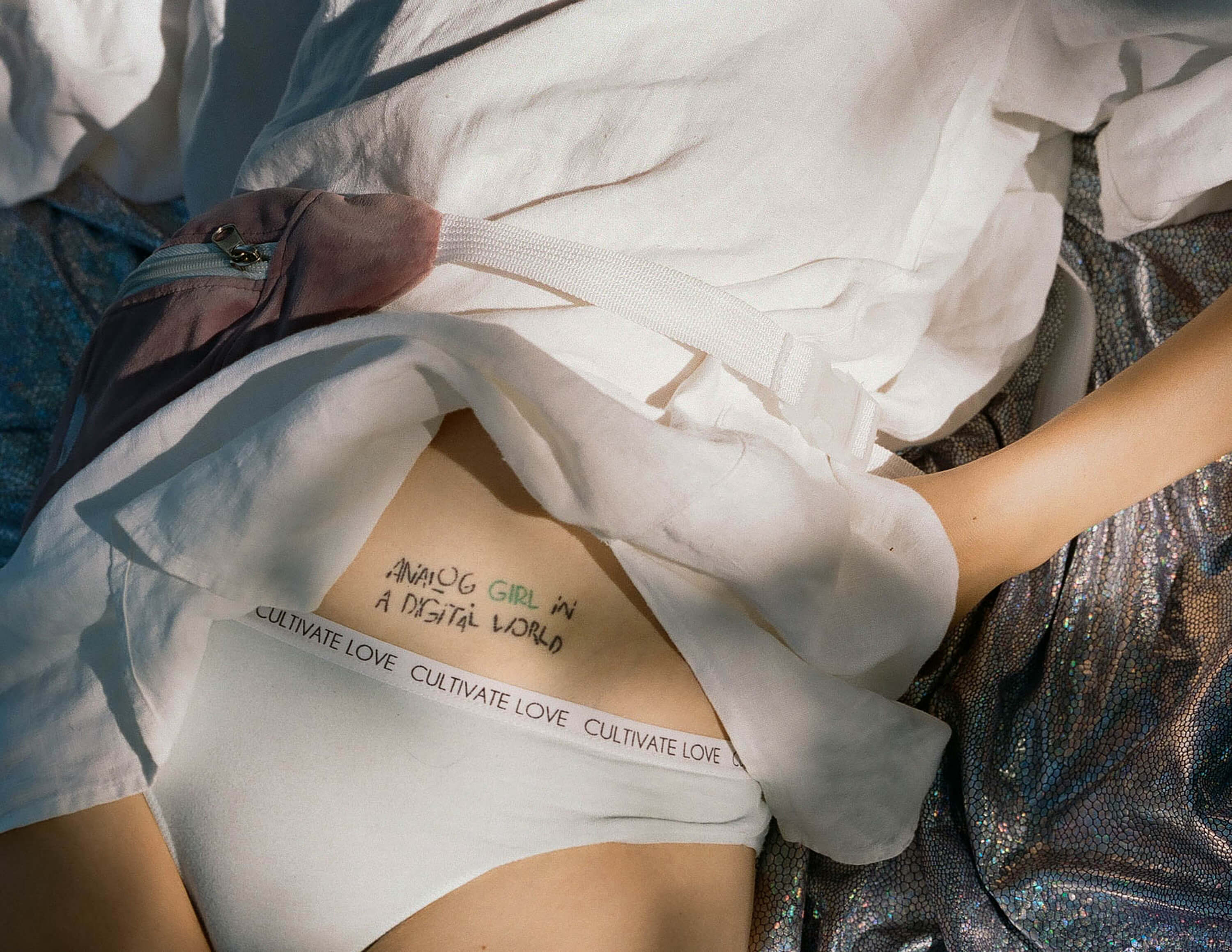

Tasha's tattoo, "Analog Girl in a Digital World.” Kyiv, 2020

Dasha facing the Kuyalnik sanatorium. Odessa, 2020

While in America, I couldn’t help but try working with local web models. Even before moving, I made friends on Instagram with Alex, an American descendant of immigrants from the Carpathian region arriving in the early 1900s. We de-virtualized, I mentioned the project when we met – and it turned out that she had been “webcamming” for many years in parallel with daytime work. Alex’s story was not much different from the stories of most of my Ukrainian heroines: semi-secret night outings, friendship with clients, and “all that fantasyland in your head.” Even the same problems with the withdrawal of money – despite the fact that webcam is conventionally legal in the US and you have to pay taxes on it.

I was also accidentally introduced to the American-Mexican Bridgette. Hers is a more “Western” story: she openly positions herself as a sex worker, runs advertising campaigns for her OnlyFans, fights for the rights of marginalized groups, and makes progress in art. In recent years, she has lost several loved ones and says that webcamming helped her cope with grief. I got along with both Alex and Bridgette, and we have “creative plans.” At the end of February, ‘On Dreams and Screens’ was published with a very cool accompanying text from Bridgette.

Bridgette openly positions herself as a sex worker. She has lost several loved ones and says that webcamming helped her cope with grief.

The pandemic was a turning point for the project. When I just started filming the American part, the world stopped, and I had the opportunity to leave out the city for the farm. For the next four months, I did not see anyone or anything except a couple of people with whom I lived, my monitor, and a wild forest teeming with bears, snakes, marmots, mad skunks, two-hundred-year-old turtles, and chubby chipmunks.

Under these conditions, the project began to expand not in breadth but depth. I made a video – one hundred percent brainchild of that enchanted period – and began to understand better what this is all about, especially when I started using Chaturbate streams not “for the project” but for my own pleasure. Rena Effendi, a classic documentary photographer, helped me return from that enchanted forest to reality. Under her guidance, I could complete ‘On Dreams and Screens’ in Ukraine. I am grateful to Tbilisi Photo Festival and Prince Claus Fund for this opportunity.

Dasha facing the Kuyalnik sanatorium. Odessa, 2020 A typical webcam set. Odessa, 2020

Alex grew up in an Orthodox, deeply religious family in Pennsylvania. This cross was given to her by her grandmother. Washington, 2020

Alex is listening to her favorite church song. Washington, 2020

A walk with Bridgette in the botanical garden. Bronx, New York, 2020

Alex. Washington, 2020

Dasha. Odessa, 2020

Streaming in the forest. Stanforville, NY, 2020

Marina. Odessa, 2019

Translated by Lubov Borshevsky