‘We Are Not Going Back to Wedding Photography’: How Kostiantyn and Vlada Liberov Started Shooting the War

Photographers based in Odesa and currently working for Associated Press as freelancers. Their pictures have been featured in Time magazine, CNN’s stories, and other major news media.

We talked with Vlada and Kostiantyn together. For our readers’ convenience, we have combined their answers.

Early career

Before the full-on invasion, we shot primarily love stories and a wedding or two here and there. Love stories were exciting to photograph, and we had a lot of clients. At some point, we even reached the level where we started holding workshops for other photographers. However, wedding photography felt tedious. We called ourselves wedding photographers for convenience, to avoid repeatedly explaining to our clients and colleagues that we had other projects.

When the full-scale invasion began, we decided to document the war in Odesa, photographing whatever was going on in the streets and how people bid each other goodbye at the railway stations. The more documentary photography we did, the more it sucked us in. Now we know that documentary photography is the real thing.

Now we know that documentary photography is the real thing.

Blunders and criticism

Switching was hard. At wedding ceremonies, we knew precisely the sequence in which things happened. At war, everything was new to us. It takes knowing in advance what happens next to get the camera to focus where you need it. You can interfere and pose people at the wedding, but not in documentary photography. A documentalist can only press the shutter release at the right moment, that is all.

Our primary objective is to photograph people as they are, conveying their emotions to the best of our ability. A person that experiences pain, despair, or happiness doesn’t necessarily look pretty. This is another difference from what we used to do: taking a picture now, we don’t think about how a person would look in the photo.

To take an aesthetically pleasing photo, you must find a flattering angle and carefully pick the objects. War photography is anything but that, even though it took us some time to arrive at this conclusion.

In spring, we shot the areas of the Kyiv Region liberated from the Russian occupation. We doubled down on the heroism of Ukrainians, totally forgetting about the horrors brought by the war, like death, grief, and destruction. As a result, our pictures ended up in Russian propaganda. Look, the Russians said, here are some actual photos from Irpin, and they show no dead bodies. Therefore, the other ones were staged!

There were other unfortunate situations. The portrait we shot in Bakhmut with the building engulfed in flames in the back got a lot of hate. We were accused of staging the shot and

We were also criticized for wearing military fatigues. The thing is that we came to the frontline wearing civvies, so the military suggested we change into something more convenient, like the kind of camouflage clothes you would find in a hunting or fishing shop. And we did. Then, foreign journalists insisted that a photographer has no right to wear a military uniform. The photos in which we wore the fatigues gave a false impression that we do it all the time, which offended many. We are sorry it turned out that way. In any case, we didn’t mean to stick out or flagrantly violate the rules. We didn’t know that camouflage fatigues were taboo. Now we do. The lesson has been learned.

Foreign journalists insisted that a photographer has no right to wear a military uniform. The photos in which we wore the fatigues offended many people.

Combat medic in volunteer medical batallion “Hospitaliers”

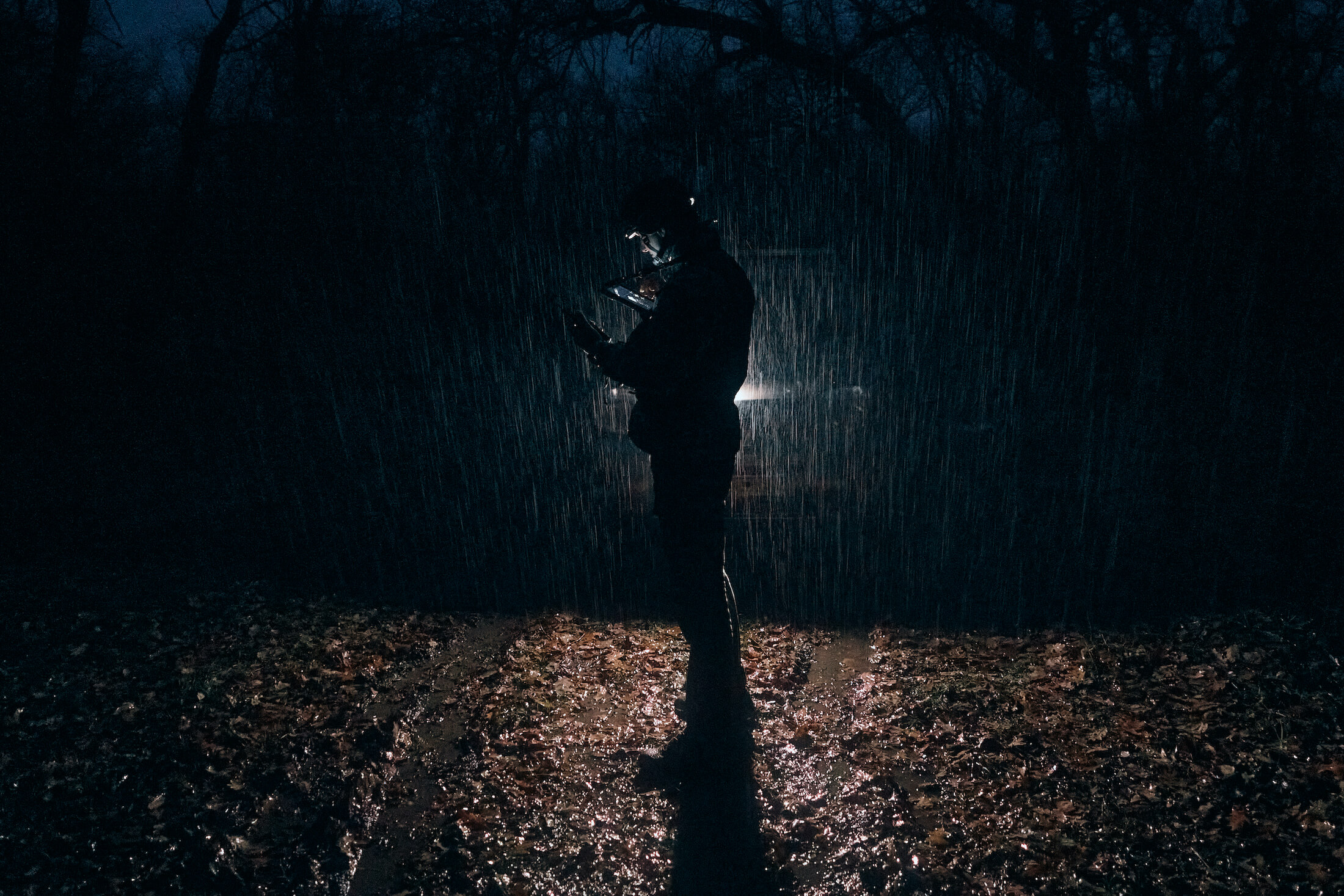

Working under fire

The military didn’t trust us at first since we were neither journalists nor documentalists. Now, they sometimes invite us to their positions.

We work together, the two of us, to provide two different perspectives on what happens. While on the frontline, we are on a tight schedule. We wake up at 6 AM, meet the military, and they take us to the position. We shoot until the evening and then go back to the hotel to sort and process the pictures. Processing photos on the same day is crucial because we don’t have time for it the following morning. The next day, it’s all the same.

Getting accredited takes time, but we make a point of always working officially, obtaining all necessary approvals, and never posting the photos by which a position can be identified.

Each picture might include information that can backfire, so we select them with utmost care. For instance, the patch of one Ukrainian unit looks like a Nazi symbol. Upon closer inspection, though, there is zero resemblance. We ensure this patch doesn’t appear in the photos because showing it in the wrong way may harm the boys.

We had a long stint shooting in the east of the country. In January, we are starting to work in the Kherson Region. Our goal here is to show how the city lives under constant shelling. When we arrived in Bakhmut this past summer, we were terrified by all the shooting, but then we got used to it. People adapt to everything, and work makes you forget about fear. However, you can never get used to how radically the war alters the people’s lives and the stark contrasts it creates. People in Soledar have been living in basements for months, while mere 60 kilometres away, in Kramatorsk, you can peacefully sip your coffee in a café or order sushi. Imagine that!

The money side of things

We shot our stories with primes, while documentary photography requires zoom lenses. We had to buy a lot of things to adjust. Besides, we have to keep switching lenses because of weather and damage. Over the ten months of our work, we spent about $20,000 on equipment.

Over the first six months of the full-on invasion, we made no money — all our trips were funded from our savings. Now we are working for Associated Press as freelancers. Documentary photography doesn’t earn us much, but we do break even, meaning we can live off that and have money to invest in our work.

Recently, we have launched a sale of our prints. We made a limited run of 500 prints for each picture and put them up for UAH 4,000 apiece. Most of the proceeds will be donated to buy a drone for the 53rd Brigade’s artillery battalion, and the rest we will live and work off.

Professional plans for after the war

Our photos that went viral on Instagram or were purchased by major media outlets are usually about the grief and pain we witnessed. At the moment, we don’t have time to reflect and pick the pictures we consider the most significant. It won’t happen until we dive into our archives after the war.

Comparing our work to our colleagues’, we see that we have room for improvement. However, they have been documenting the war for eight years already, and we are just starting out, so we put every effort into what we do.

Perhaps, we can switch to portraits after the war, but we are not going back to wedding photography, that’s for sure. It takes a particular emotional state to photograph love, but we feel the war has broken something inside us. Besides, there is no way back once you go documentary.

After the war, we are not going back to wedding photography.

New and best