10 Favorite Photographs of Victoria Ivleva

Russian photographer and journalist. Was born in Leningrad, lives in Moscow. Graduated from the Journalism Department of Moscow State University (MSU). Has worked in many hotspots around the globe, contributes to Russian and foreign publications. Holds the Golden Eye Award from the World Press Photo for a shoot she made in the destroyed reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, as well as a German Gerd Bucerius award.

I can’t say that the photo of a woman in a pool of blood is my favorite. I’ll call it scary. Stunning. An anti-war icon. This is exactly what collateral damage looks like — a young beautiful thin-legged woman, who tried to flee from war, and wore flats from different pairs in a hurry. She didn’t manage to flee. She managed to become a symbol. I had this photograph with me on a March for Peace in Moscow in spring 2014.

This is the only photograph of her I have, no repetitions or variations — the people I was with did not want me to shoot the dead. This was at the end of 80s during one of the wars in the collapsing empire.

I don’t usually crop pictures, this must have been the only occasion. There are the three young mothers, who are serving terms for drug dealing. They had their babies in prison, and they live separately there: mothers in barracks, and children in special facilities for them, where the mothers can come in only to feed them. Women and children behind bars is a big theme I have been shooting for many years. It is usually a rough kind of shoot. Here though, on the contrary, it is surprising how soft the lines are. I have been waiting for this moment, and I managed to capture beauty and defenselessness. This work reminds me some kind of a fresco.

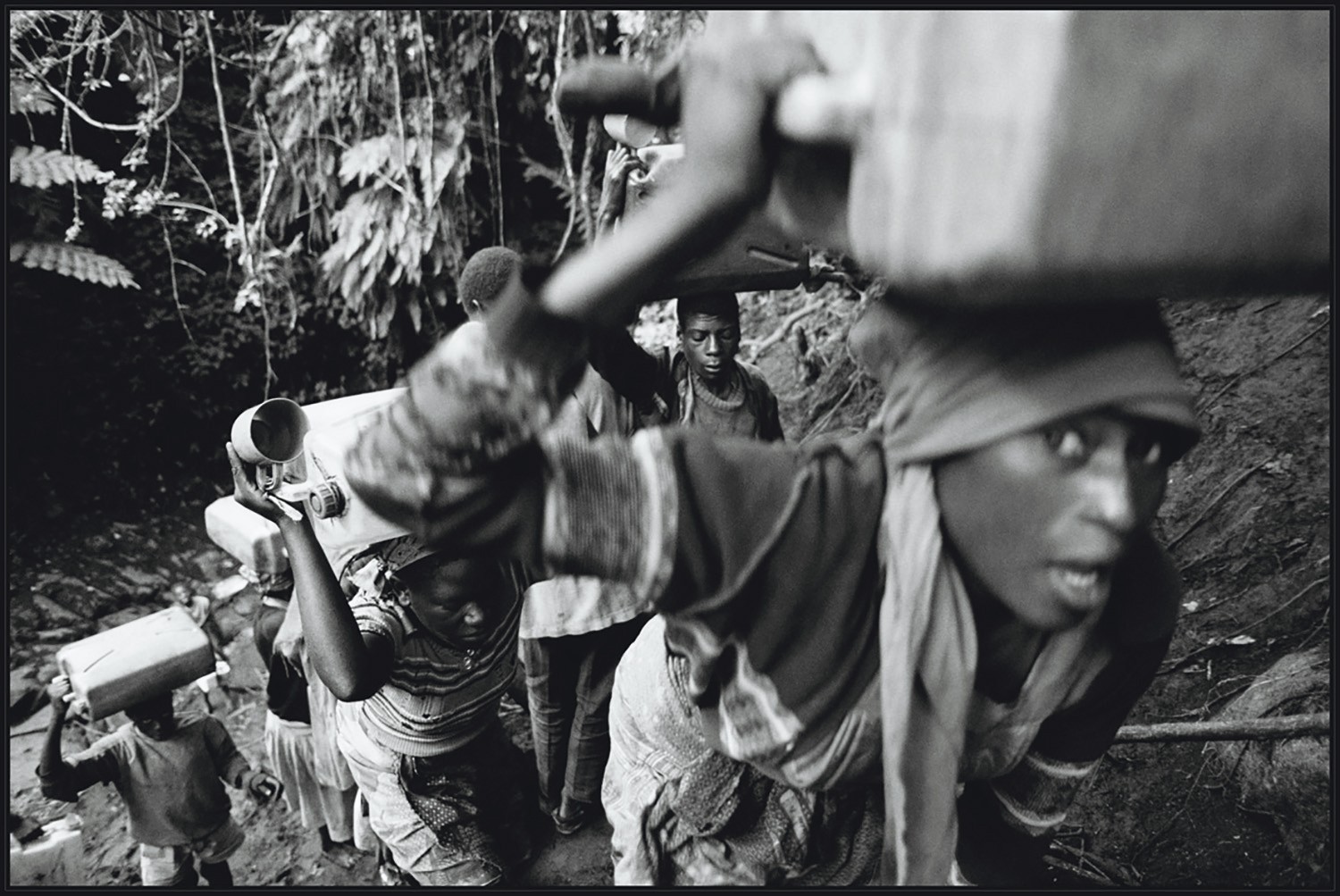

This is a photo from my first trip to Africa in 1994. I was in Rwanda, which was in the middle of a war, and in Zaire, a neighboring country, where by that time there were more than a million refugees from Rwanda, and there was a massive water shortage. This photograph is from my trip to get water. I walked alone together with a whole bunch of refugees with canisters. The composition is good, and, of course, the blurred woman in the foreground is great — it conveys the heaviness of her load and at the same time her surprise at seeing me, a white person. This does not happen often, having different emotions in one frame.

I sometimes ask people when I show them this photograph, where they think it was taken. And almost everyone says: Paris! This is right, this is Paris, a Russian emigrant named Olga and her dog — a very stupid dog of Russian wolfhound breed. I am glad that this photograph creates this Paris feeling. I think this is thanks to the great light from the balcony door, and Olga’s wonderful costume, and her posture. I like the two diagonal stripes — arm in the shadow and the dog’s snout, they interact well. This photograph is from my first trip to Paris in 1988. This was my first ever trip abroad, and all the memories of it are as wonderful as this picture.

Afghanistan. Former Soviet military air base in Kunduz city in the north of the country. The children are Tajik refugees who had to leave Tajikistan during the civil war in early 1990s.

For some reason few people out there were interested in this war and the fates of Tajiks — during my several trips to Tajikistan and Afghanistan I haven’t met a single journalist or photographer in refugee camps. Unfortunately, this little known war still remains little known.

The refugees settled everywhere — they even filled all the cells of the former municipal prison. The Afghanis fed them — the rich local merchants donated rice. The Soviet air base in Kunduz was also full. I think, it was especially hard for children, nobody paid any attention to them, and I was a great entertainment for them. I later asked them to climb on the abandoned Soviet military trucks, where the laundry was hanging, and took several pictures.

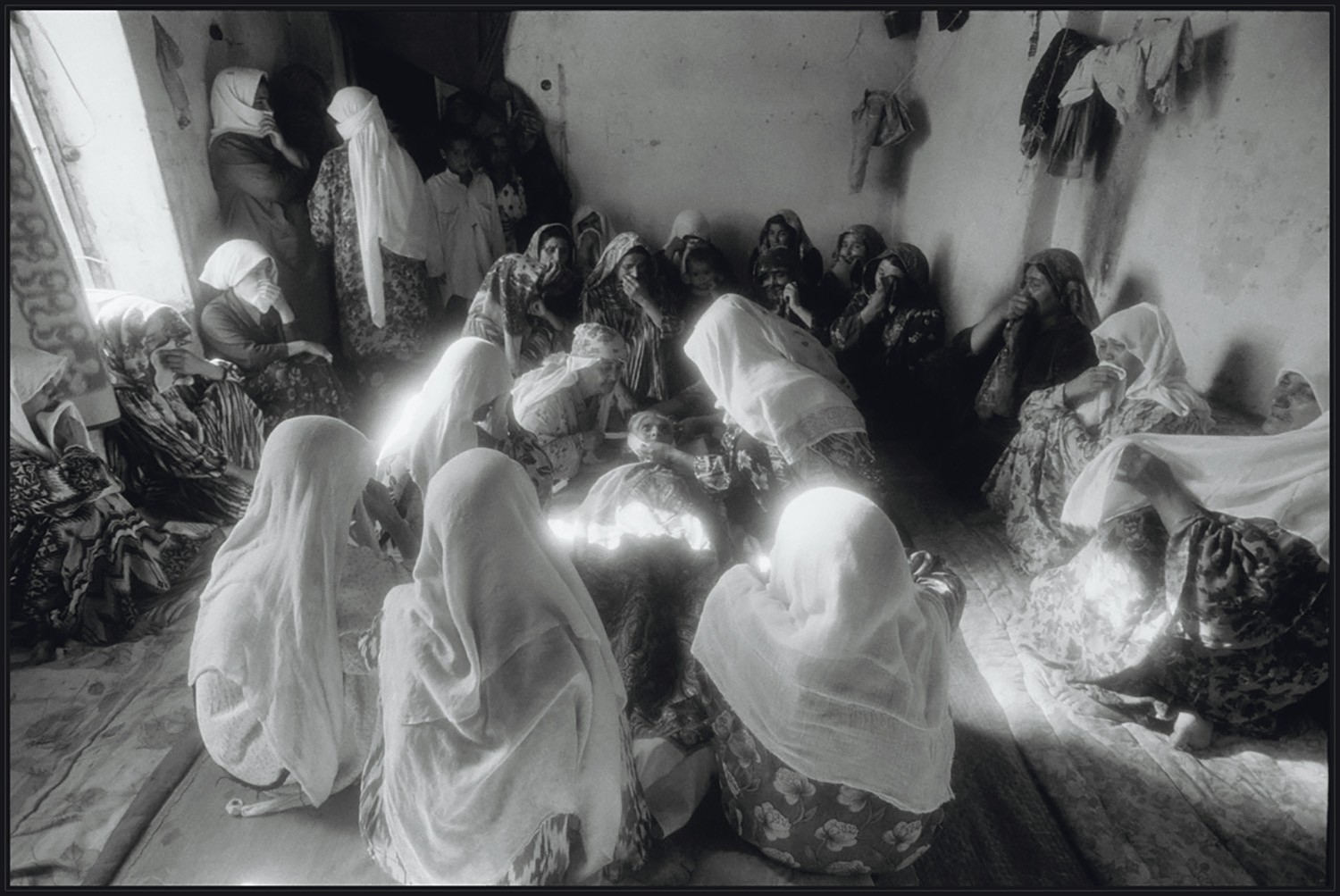

This is also Afghanistan. And also Tajiks. Tajik women, to be exact, who gathered at the funeral of their friend. People often ask me, how I managed to shoot in refugee camps. To be honest, this was never a problem — the refugees saw me as someone who is compassionate of their suffering and who is equal to them. Being equal to people is in general an important quality for any journalist. This photograph is filled with amazing light, enhanced by the whiteness of the mourning shawls. I like the faces of the women, united by common grief. Vsevolod Tarasevich, a famous Soviet photographer with whom we were friends in the late years of his life, once told me: “A photograph should be interesting to take a long look at”. I think it is interesting to take a long slow look at this photograph, and think about the meaning or the absence of the meaning of life.

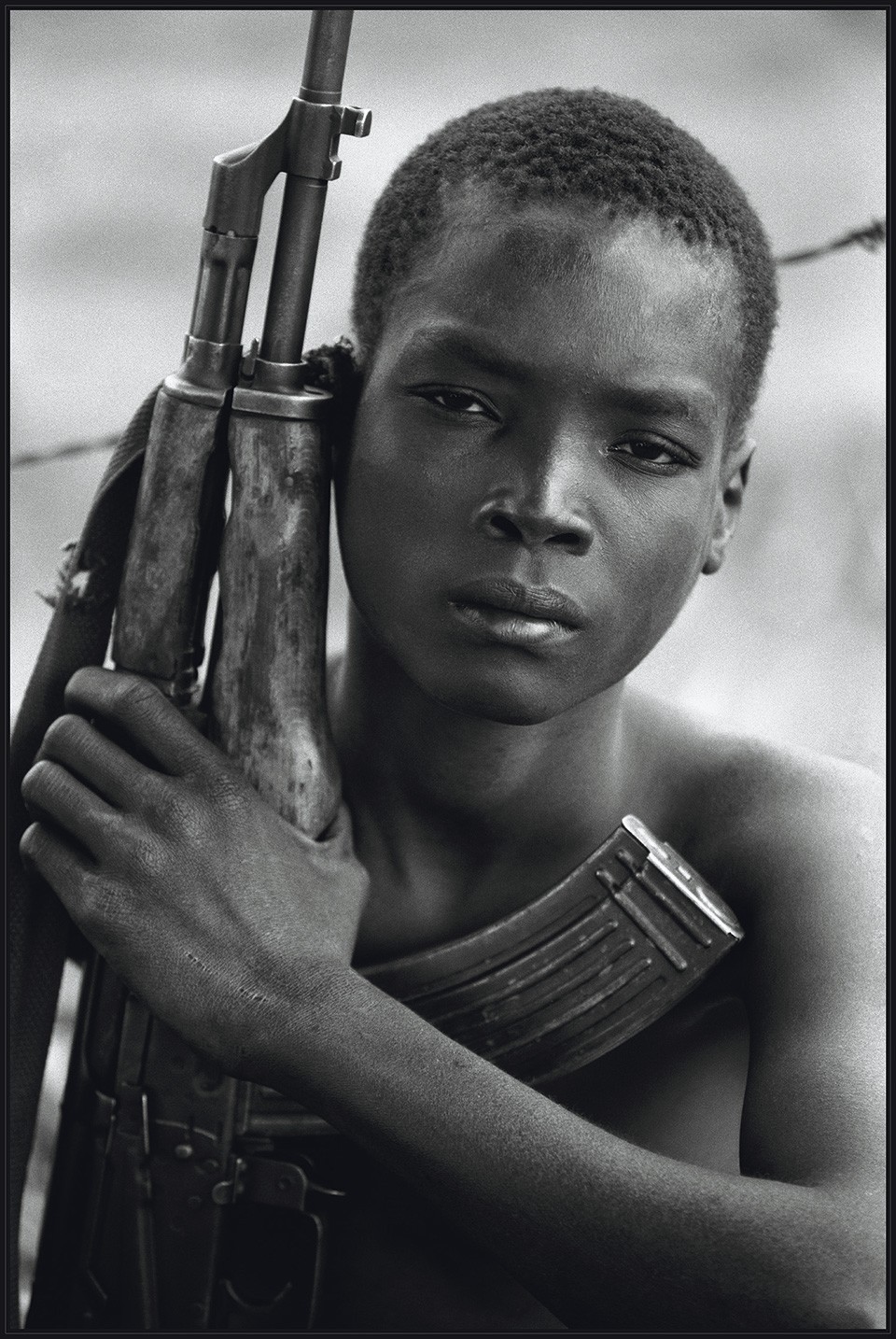

The boy with a Kalashnikov is my friend, and possibly this friendship is the best thing that I have done in life. The story of this boy is about making even the most desperate person believe in good. We met at a rehabilitation center for child soldiers in the north of Uganda.

He was 15, and he spent half a year in the awful child army. It was the first day of his freedom.

He told me that he wanted to become a doctor. I helped him go to school and continue studying. He turned out to be a good student. And then my friends and I helped him some more, and he came to Russia to study to become a doctor. He is now a third year student in the People’s Friendship University of Russia. He just came by to catch up the other day. The Kalashnikov in this picture is the same one he had when he ran away from bandits. But in the past several years his hands only hold a pen. I am very glad that I contributed to it, and that what was dreamt of in the jungle came true.

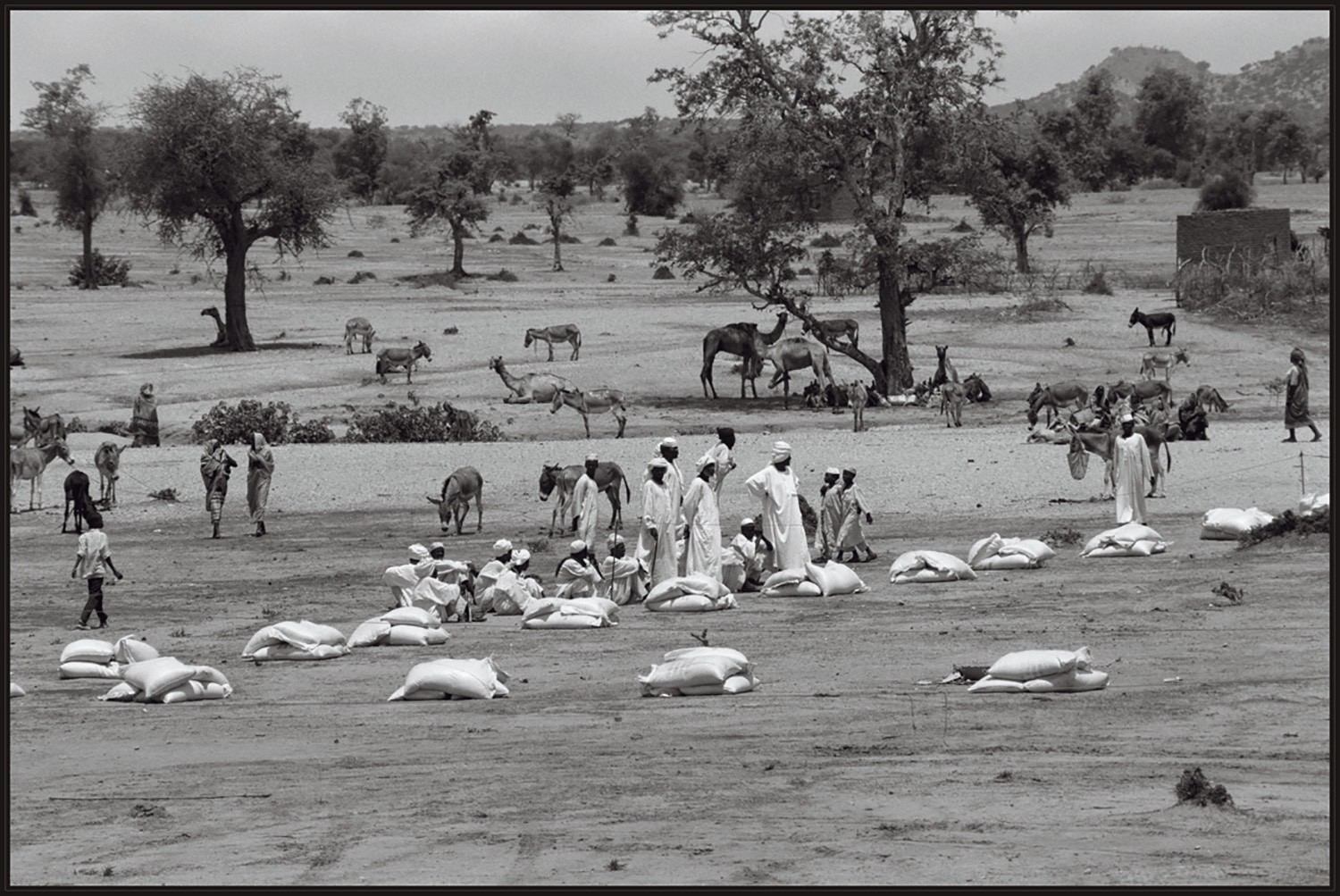

This is also Africa, but a completely different part of it. It is Sudan, the Darfur region. I was there with a food convoy from the Red Cross. We fed twelve and a half thousand people. And it was an incredibly happy feeling. I like the photograph because it is multi-layered, there are so many plots, so many stories: about the trees, the camels, the Bedouins, women and the bags of grain. I also like it for the soft change of different shades of grey and clear, distinct figures. It is a bit like Bruegel. Only in Africa.

This picture is funny, isn’t it? I call it From Here to Eternity — this is about the grandpa who is looking through binoculars. I took it in Kyrgyzstan, on a pasture where I spend several days. You can see from the photo how different the characters of children are. I also like it that the car, like a backdrop on stage, separates the grandpa and his grandchildren from another life. And there is always this mystery for me here: what does the grandpa see in his binoculars? We will never find out. The beauty of photography is asking the questions which have no answers.

This is an outstanding day in the history of my country. August 21, 1991. The end of the inglorious putsch (or, it seemed then that it was the end. Life proved that the putsch just lay low and changed shape). Of course, there is the feeling of freedom in this photograph — it is in the flying flag, in the people freely walking around, in the sun piercing through the fabric.

The interesting fact is that this photograph was printed large-size in the Independent newspaper in England. And nobody — not a single person — paid attention to what is on the flag.

And this was the flag of independent Azerbaijan from 1918. Who knew about it back then, in 1991? Several hours after I took this photograph, the monument of Felix Dzerzhinsky was hooked to cables, lifted and taken away from the square. This was accompanied by our happy cries. We were naive to think that getting rid of the stone idol was enough to make the country free. Only after twenty years Maidan showed us how much freedom really costs. And still the memories of August 21, 1991 are very warm for me.

New and best