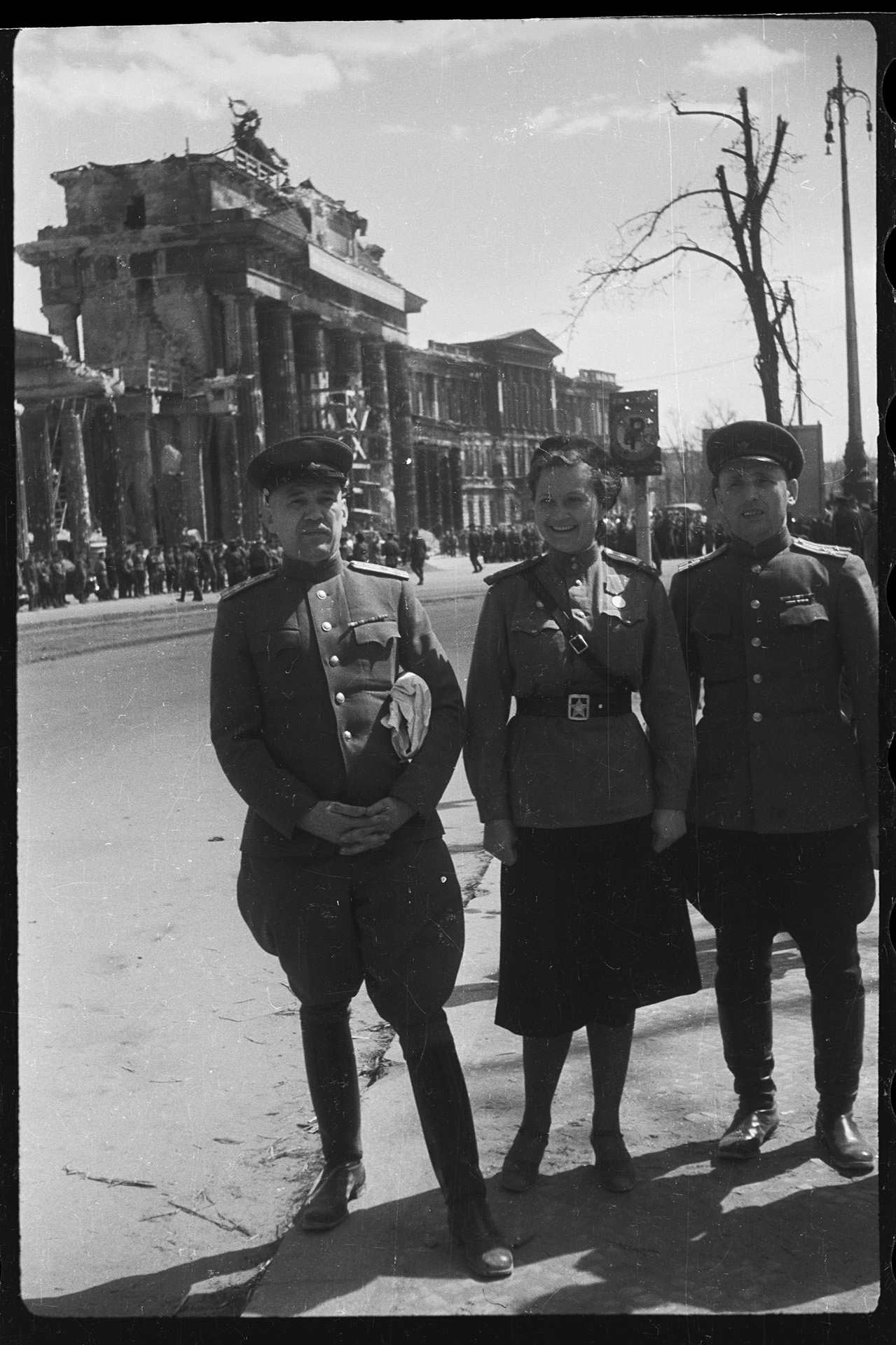

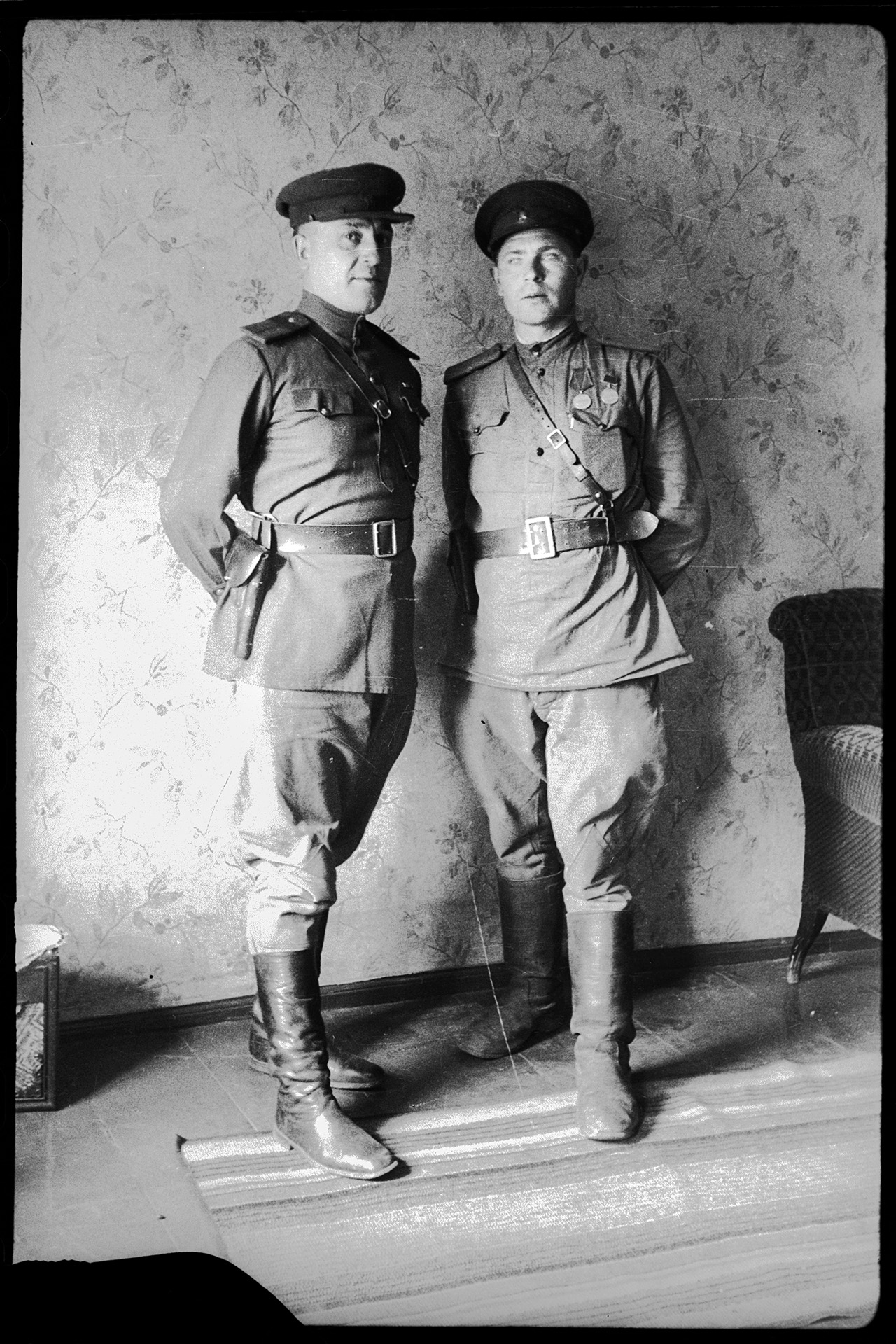

Soviet Life of the German Capital: Berlin in May 1945

On April 30, 1945 at 3.30pm Berlin time when the Soviet army was within two hundred meters of the Fuhrer’s bunker, Hitler bit on a vial of poison. Weidling, the commander of the Berlin defense, thought that suicide was not an option for an officer whose soldiers were still fighting. He sent the parliamentarians to the position of the Red Army, and addressed the Berlin garrison:

“The Fuhrer abandoned all who had sworn loyalty to him… The lack of heavy weapons and ammunition and the general situation make further resistance pointless. Every hour that you continue to fight only prolongs the terrible suffering of the civilian population and of our wounded. Anyone who still dies fighting for Berlin makes this ultimate sacrifice in vain. I demand that you immediately cease fighting.”

The capital of Germany capitulated on May 2.

“Their padded cotton jackets were grease stained and threadbare, their transport a hodgepodge of antiquated trucks and horse drawn wagons piled with looted furniture, and more than half of them traveled on foot. They marched beside the autobahn, shepherded by NCOs on tubeless German bicycles. Even the famed Russian artillery pieces were practically invisible under layers of dried mud.

These were, indeed, the men of the armies which had fought and beaten two-thirds of Germany’s land forces on the Eastern Front while the magnificently equipped British and Americans had trouble enough dealing with the other third in Normandy, Italy, and along the Siegfried Line. They were stocky, hard-faced peasants and herdsmen from the Steppes. They looked inured to hardship,” Australian war correspondent Osmar White described the victors.

The tales made up by the German propaganda which described the horrors of possible occupation to Berliners were magnified by the stories of refugees from the eastern provinces who described the real crimes of Red Army soldiers against the civil population. In the winter and spring 1945, in only one of the city’s districts 215 people committed suicide before the advancing Soviet troops reached them.

On May 2, writer Vladimir Bogomolov, a counterintelligence officer at the time, came to Berlin: “We enter one of the undamaged homes. Everything is dead quiet. We knock and ask to open the door. We hear that people behind the doors are whispering, talking in muffled and worried voices. Finally, the door opens. Ageless women huddled in a close group, scared, bent low and obligingly. German women are afraid of us, they were told that Soviet soldiers, especially the Asians, will rape and kill them… Fear and loathing in their faces. But it sometimes seems that they enjoy their defeat — so obliging is their behavior, so sweet are the smiles in their faces and their words.”

The locals who lived in the German lands occupied by the Red Army were hardly showing any resistance, so they were not repressed. However, Soviet soldiers are accused of mass rapes.

“Berliners remember that, because all the windows had been blown in, you could hear the screams every night. Estimates from the two main Berlin hospitals ranged from 95,000 to 130,000 rape victims,” British historian Antony Beevor claims. According to the estimates of professor Atina Grossmann, in the post-war months the women of the city wrote between 20,000 and 100,000 affidavits — written reports of rape that were required to have the right for a free abortion.

“Servicemen comrades! You are being seduced by women whose husbands have been to the brothels all over Europe, have contracted diseases there, and the passed them on to their German women. In front of you are also those German women whom the enemy has deliberately left behind to spread venereal diseases among the Red Army soldiers and thus make them unfit for service. With what eyes will you be looking at your family, if you bring an infectious disease back home to them? How can we, the warriors of the heroic Red Army, be a source of infectious diseases in our own country? NO! Because the moral character of the Red Army warrior should be as pure as the character of his Motherland and his family!” the leaflets with this texts were distributed in the units of the 1st Belarusian Front.

#1 Decree of the Soviet commander of Berlin banned the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and all affiliated organizations and prescribed all servicemen and top management of public institutions to show up at the commander’s office for registration. Utility companies (power plants, sewerage, public transport), medical institutions, food stores and bakeries were to resume operation. Workers and public servants were to remain in their workplaces and continue performing their duties.

On May 17, Arthur Werner, the 68-year-old engineer who specialized in bomb shelter construction, was appointed oberburgermeister of Berlin. Both of his sons were in Soviet captivity.

The night clubs continued to work in the half-destroyed city. In Potsdamer Platz it smelled of sewage and decomposing bodies, but in Femina cabaret Soviet, British, and American officers were dancing with women. A bottle of wine cost $25, a pack of American cigarettes — $20, and a horsemeat burger with potatoes — $10.

“Cheeks were as delicately tinted and lips as tacky-looking as if Hitler had won his war. A number of women wore sheer silk stockings,” Osmar White recalls. The programme of the night included ‘Russian’ dancing.

White wondered: “Baffling people, these Russians! Rape and apology. Theft atoned by gifts of food. The savage sacking of a blasted city and, within days, attempts to rehabilitate it.”

In the post-war memoir he recalls how under the Soviet command life started coming back to the ‘horrendous garbage heap,’ which was Berlin in May 1945. The works on clearing were started, and the efforts to stop the spread of the epidemic were successful.

On May 15, five categories of food rations were introduced. On average, every Berliner would get 400-450 grams of bread a day, 50g of grain, 60g of meat, 15g of fat, 20g of sugar, 50g of coffee, 20g of tea. Vegetables, dairy products, salt were distributed based on availability.

“I believe that the Soviets in those early days did more to keep Berlin alive than the Anglo-Americans could possibly have done,” the Australian reporter concludes.

Photo: Valery Faminsky, Arthur Bondar’s private collection. Berlin, May 1945.