On the Edge of the Snow: Life in the Northernmost Settlement in Russia

Author and editor for the Siberia: Joining the Dots project. Lives and works in Krasnoyarsk. Studied journalism and Art History. Graduated from the School of Cultural Journalism funded by the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation, is taking a FotoDepartament course, Overcoming Photography. Studies at the School for Research and Text of the Russian Culture Fund. Published her work on Colta.ru, Gorky, Seans, Siburbia.ru, Siberian Forum, and many other media outlets. Works as a journalist for RBTHtravel.

Freelance photographer from Krasnoyarsk, majored in Engineering. Contributes to the Siberia: Joining the Dots project. Participant of the exhibition Siberia. Poles at the museum complex Peace Square in Krasnoyarsk and the State Center for Modern Art in Tomsk.

— There are no cinemas or mobile Internet, buses, coffee shops, supermarkets, or outdoor advertising. Every single person here has seen polar night and the green iridescence of the Northern Lights, knows what to do if they encounter a polar bear or how to react to a storm warning, and anticipates Arctic poppies and a scheduled flight. This is Dikson, the northernmost settlement of Russia.

Dikson is habitually called ‘the edge of the world’: it is located in the north of Krasnoyarsk Krai, in the Yenisei Gulf on the Kara Sea, the outskirts of the Arctic Ocean. The distance between Dikson and the nearest big cities, Dudinka and Norilsk, is 500 kilometers of uncivilized tundra. Access to the settlement is restricted, and you can get there only with a special pass, and only on an old AN-26 plane, which flies from Alykel Airport once a week, if there is no blizzard or fog. For the locals, everything that is not Dikson is the ‘mainland’. The ‘mainland’ has Siberia, wild taiga, roads, the usual change of day and night. ‘On the edge of the world’ there are stilt houses, “Have you seen the Arctic Fox chase the dog in the yard?”, wild tundra, open to all the winds, and endless ice, the Arctic.

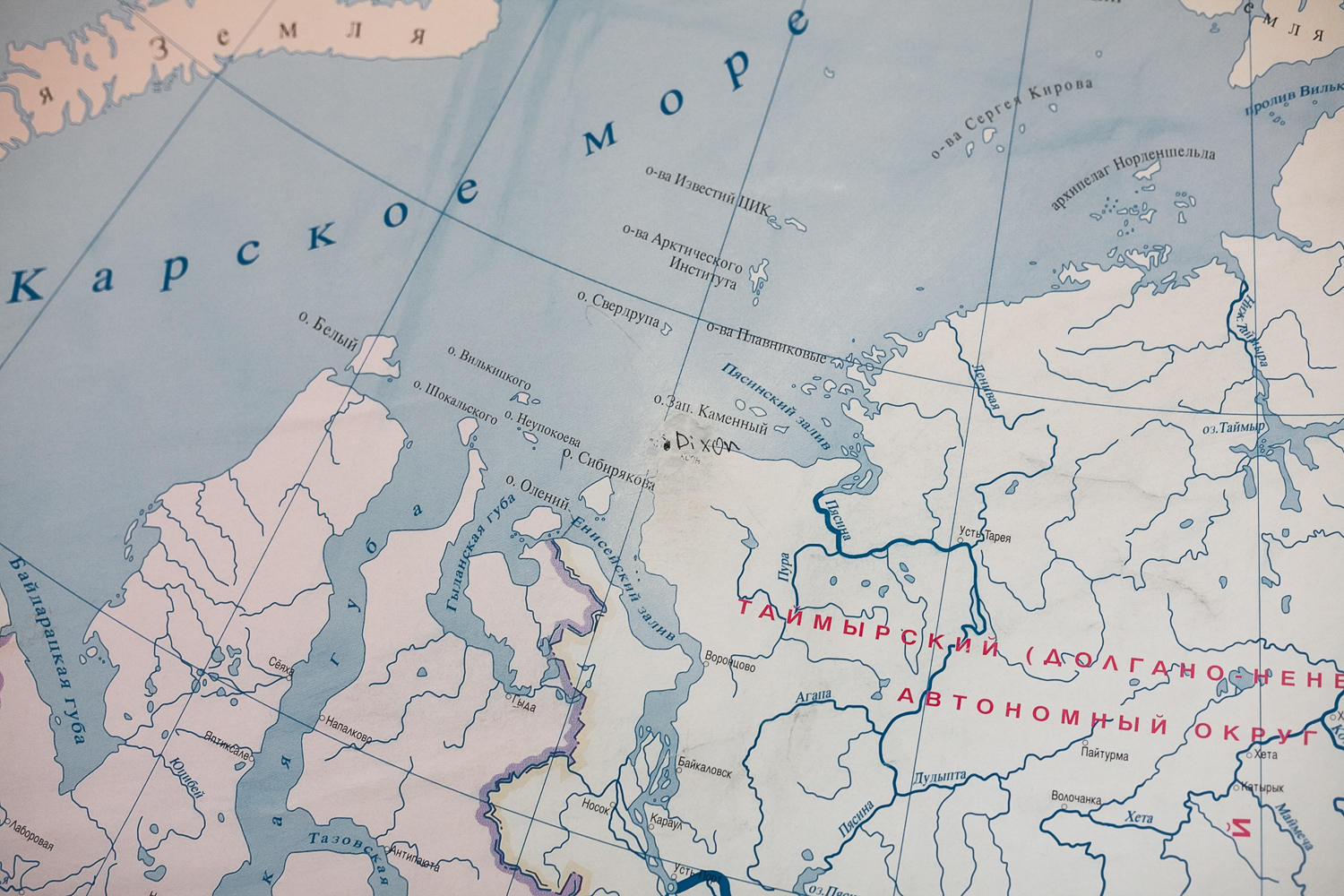

The map of Dikson in the settlement’s school #1.

Dikson is located on the coast of Kara Sea. Part of it is on the western edge of Taymyr Peninsula, the other part is on the eponymous island. There is a 1.5km strait between them, which becomes a winter road in winter.

The average temperature in Dikson in December and January is -25℃, but it can get as cold as -40℃. The low temperature combines with the storm wind, which reaches the speed of 15-30m/s, is considered to be the most unfavorable weather. On such days, a storm warning is issued, and schools are closed. The polar night in Dikson lasts approximately from mid-November to early February. It is usually darker than in the neighboring Norilsk, Dudinka, Igarka, and Khatanga. The Northerners say that for some, the polar night ends as soon as a small part of the sun shows up, while for others — only when the round ball is hovering over the horizon.

Dikson is 102 years old, but its history is more than a biography of a lonely dot on the administrative map of modern Siberia. It is the story of people and states encountering the Far North, and it is much longer than a century. Back in the 11-12th centuries the Pomors, people from Veliky Novgorod, traveled to ‘all ends of the great sea-ocean’ looking for new industries and trading partners among the Samoyedic peoples. In the early 17th century, Mangazeya, the first Russian fortress city beyond the Polar Circle, became a base for the colonization of the vast territory in the north of Siberia: merchants and

On August 15, 1875, Swedish geographer and seafarer Nils Nordenskiöld entered a ‘convenient harbor of a small island in the Yenisei Gulf’ on the hunting vessel, Preven. “I hope that this harbor, which is now empty, will soon turn into a gathering spot for many ships, which will facilitate relations not only between Europe and Obsk and Yenisei river basins, but also between Europe and Northern China,” Nordenskiöld wrote in his diary, and then named the harbor Dikson (for Oscar Dikson, who sponsored his polar expeditions) and put it on his nautical charts.

Fur tribute exacted from the indigenous peoples of Siberia in Imperial Russia

In the 20th century, the North was for the USSR a place of trade and field development, exile and scientific research, and of course, the construction of new Polar cities and settlements. Among them, Dikson was the ‘capital of the Arctic’, where meteorologists and builders, teachers and hydrographers, military and polar pilots, radio operators came from different parts of the Soviet Union to ‘civilize the North’. Nowadays, this Arctic settlement, just as many northern settlements in Russia, is going through very difficult times. In the 1980s, the ‘golden years’ of Dikson, it had a population of 5,000 people. Currently, according to the official statistics, there are less than 600 people living there, but the locals claim this number is no more than 500.

Robert Prascenis with wife Marina near their home. Robert came to Dikson in the mid-1970s, currently works in the administration, and collects archive photographs of the settlement. “People used to be kinder, there was no spite, and now more and more random people come here,” Robert says.

Dikson is located in the permafrost area, so just like everywhere in the Arctic, the settlement has stilt houses. This creates an air cushion between the building and the ground, so that it wouldn’t transfer its heat to the ground and the ground wouldn’t start moving under it.

Currently, there are only several households living in a house such as this one. Sometimes in the winter the snow rises up to the middle of the door, and the inhabitants have to clear out their way outdoors from the inside.

Various kinds of snowmobiles and ATVs, some dating back to the Soviet times, is the most popular means of transportation in Dikson. This is the only way to get through the snowy tundra in winter.

During the polar night, the streets of Dikson are empty for the most part of the day. The settlement comes alive only early in the morning when the locals go to work and then at 5-6pm when they come back home, pick up children from the kindergarten, go shopping, or to run some other errands.

People here have a habit of saying ‘on Dikson’, not ‘in Dikson’: historically, the settlement started from the island in the Kara Sea, and later expanded to the Taymyr Peninsula. That’s why Dikson has two parts, the island and the mainland, divided by a 1.5 km strait. In 2009, access to the island was restricted, and now it is almost uninhabited. People moved to the mainland, the streets are empty, the wind knocked out the windows and doors in the abandoned houses, the empty school #2 has only hare tracks on the snow-covered floors. The only places where there are still lights on are the hydrometeorological station and the airport.

There is more life in the mainland part of Dikson. There are people and snowmobiles in the streets, shops are open, there is a school gym, a library, and a church. However, there are more and more boarded-up windows and closed doors here as well, and only several monuments to the polar explorers and ships in the harbor that serve as reminders of the former greatness of the “gates of the Arctic.”

Alexander Surkov, graduate of school #1, currently a student at the Polytechnic Institute of the Siberian Federal University in Krasnoyarsk. “There are too many people in Krasnoyarsk, it gets on your nerves. On Dikson, you go out — and there is no one. I don’t like the buses, and you have to pay 22 rubles to take them. On Dikson, you can get anywhere on foot. Trees also take getting used to. In Dikson, we only have artificial glowing trees, and the tundra only has very low larch trees. To be honest, at first I really wanted to go home. I missed my parents. On Dikson, I could see the sea from my window, and in Krasnoyarsk I see a construction site. Compared to Krasnoyarsk, Dikson is special,” Alexander says.

Mikhail Degtyaryov and his wife Zinaida are one of the few people who fish in Dikson after the 1990s. Their children live in Belarus and Canada, but the fishing family doesn’t want to leave for the mainland, because they don’t do well with heat and because away from Dikson they don’t feel that anybody needs them.

Between the 1960s and 1980s, the shores of both the island and the mainland part of Dikson were covered in small mobile houses, where the fishers and hunters would store boats, equipment, nets, and other things one would need when hunting in tundra. The places with many mobile houses were called ‘Shanghai’, and now they are empty.

Dikson’s waters are the home to some valuable whitefish. In the settlement, they go for 200 rubles per kilo, and it the mainland its price goes from 500 rubles and higher. The locals usually don’t buy different kinds of whitefish separately, but take a bag with a northern fish mix.

The winter road in Dikson that connects the island and mainland parts of the settlement goes on the frozen Kara Sea Gulf. “In winter, people take an ATV, in summer — a cutter boat. In the thaw season, when the ice is melting, neither an ATV nor a cutter are any good, and they have to order a helicopter. The same happens in autumn.”

The network of polar stations, a geophysical observatory, a port of the Northern Sea Route, Marine Operations Headquarters, a network of coastal airfields, polar explorers clubs, a fish factory, an art gallery — all of it is now only in the local history books, the archive copies of the Soviet Arctic, and the memories of people who came to make a home in the harsh Far North. A border post, an airport with no heating, a hydrometeorological station, a boiler and a diesel heating house, a school, a local administration, a library and several shops — that’s all there is for today.

And yet, people live in Dikson. They hunt in the tundra and fish, teach their children to draw and solve equations, write dictations and take Unified State Examinations, collect archive photographs and bake bread, look after the boilers and follow the wind speed, live through the polar night and greet the first sun. Here in Dikson, every abandoned winter hut, every closed door and every gaping doorway or an illuminated window is history. The history of exploring the Northern Sea Route, the story of ‘conquering the North’ in the USSR times, but most importantly, the individual story of a family or a person.

One of the acting buildings of the hydrometeorological station on Dikson Island. There is a radiosonde on the roof — the device used to measure different parameters of the atmosphere, such as pressure, relative humidity, or temperature.

Anatoliy Bukhta, oceanographer and former director of the hydrometeorological station: “The ruin started in the 1990s. The wages came half a year late, and we got expired products instead. It was hard, it broke many people: they wanted to live and do something on Dikson, and then they didn’t. Many of the people my age started drinking too much and died, but it is not their fault -- everybody has their core and their limit. You have to take into account that many people who used to work as engineers started sweeping the streets. They could not cope with this psychologically.”

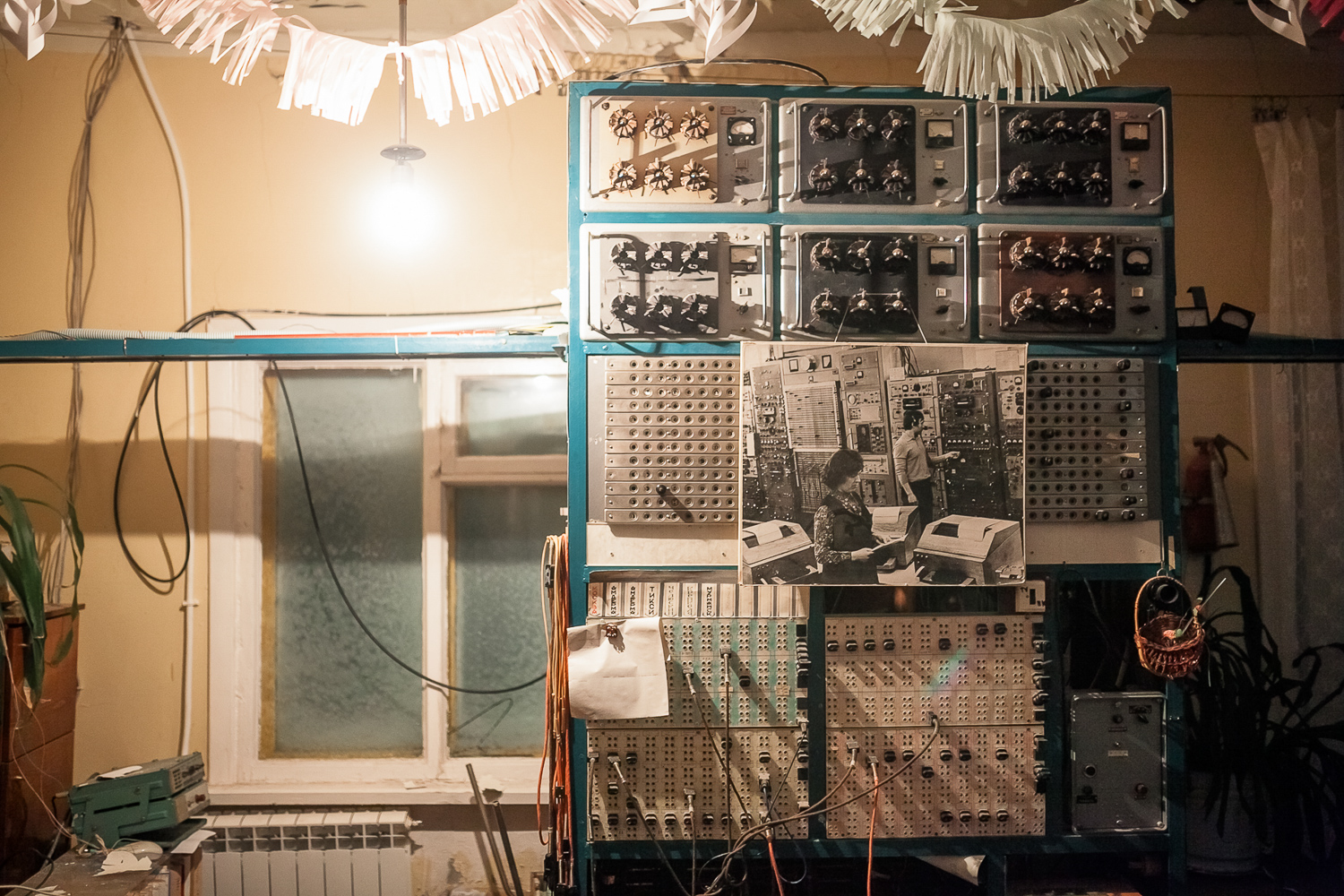

Soviet equipment in the old building of the hydrometeorological station.

One of the streets on the island part of the settlement. The snow-covered wooden path is installed on empty metal fuel barrels, but you can’t see it in the winter. The recycling of rusty barrels is one of the main Arctic issues in Russia, Canada, Norway, and Alaska.

Monument to the marines of the Northern Fleet who defended Dikson during WWII was erected on the island in 1973. On August 27, 1942, a German cruiser, the Admiral Scheer, attacked port Dikson. Icebreaker Sibiryakov was fired upon and sunk in the battle. However, having met the resistance of the patrol ship Dezhnev and artillery fire from the shore, the Sheer retreated. Some of the crew were killed.

Abandoned room of an apartment building on Dikson Island. Before leaving the island, Dikson citizens boarded up the windows and the doors, but the Arctic wind knocked them out, that’s why in the winter the interiors of many houses are covered in snow.

The view on the Plane Harbor, abandoned by fishermen and hunters, ‘Shanghai’ and winter sea gauge. “The mobile house was both a hangar for the boat, a workshop, and a small accommodation where you could rest or hide from your wife’s anger. Often people would carve a freezer under the house, with small chambers for storing meat or fish. By the mid-1990s, the number of mobile houses was considerable, they are located chaotically, that’s why after a night out with friends it was sometimes difficult to find your way home. That’s why this district was called ‘Shanghai’,” Anatoliy Lomakin, a Dikson citizen, says.

#2 school classroom on Dikson island covered in snow. “For September 1, we ordered gladiolus flowers to be delivered by a helicopter. We had sandwiches with butter and black caviar… It was amazing,” driver Dmitriy Asovskiy recalls.

Nameplate near the Dikson airport building. The airport takes in passengers once a week, on Wednesdays. Sometimes, because of the snow, fog, or other ‘unfavorable weather conditions’, people in Dikson have to wait for the Dikson-Norilsk or Norilsk-Dikson flight for two weeks.

New and best