Drone Survival Guide Creator about Design as an Activist Tool

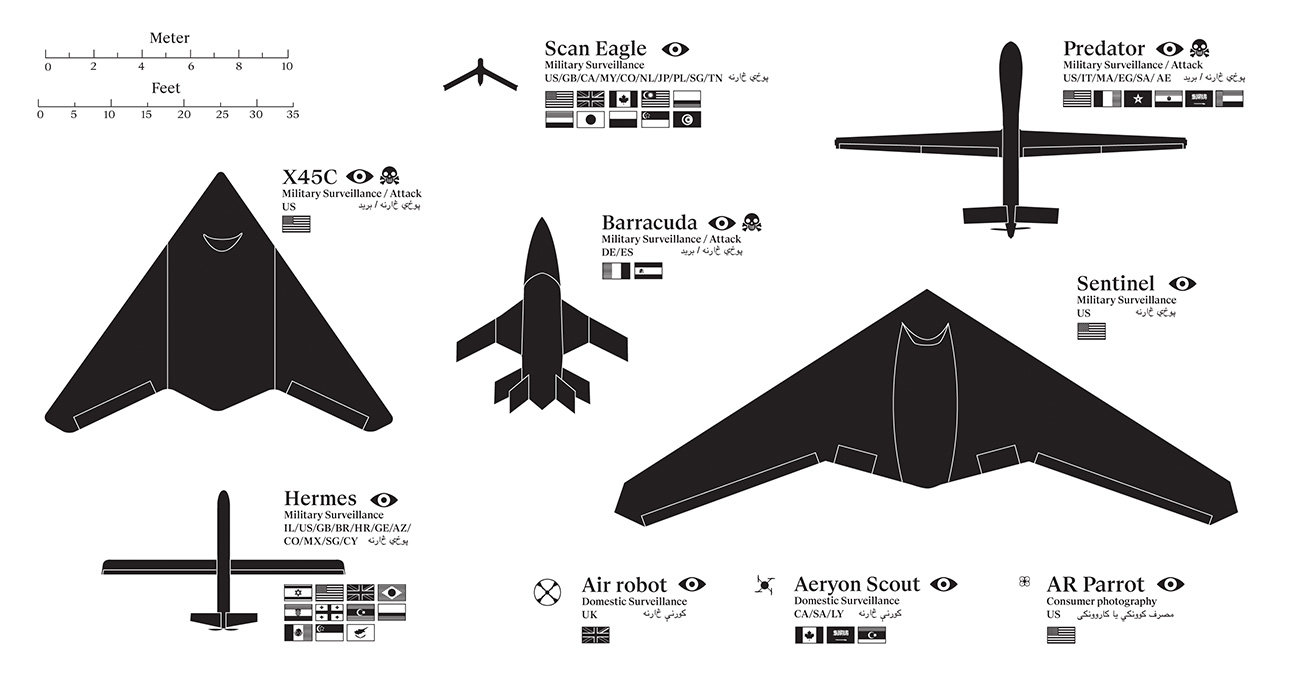

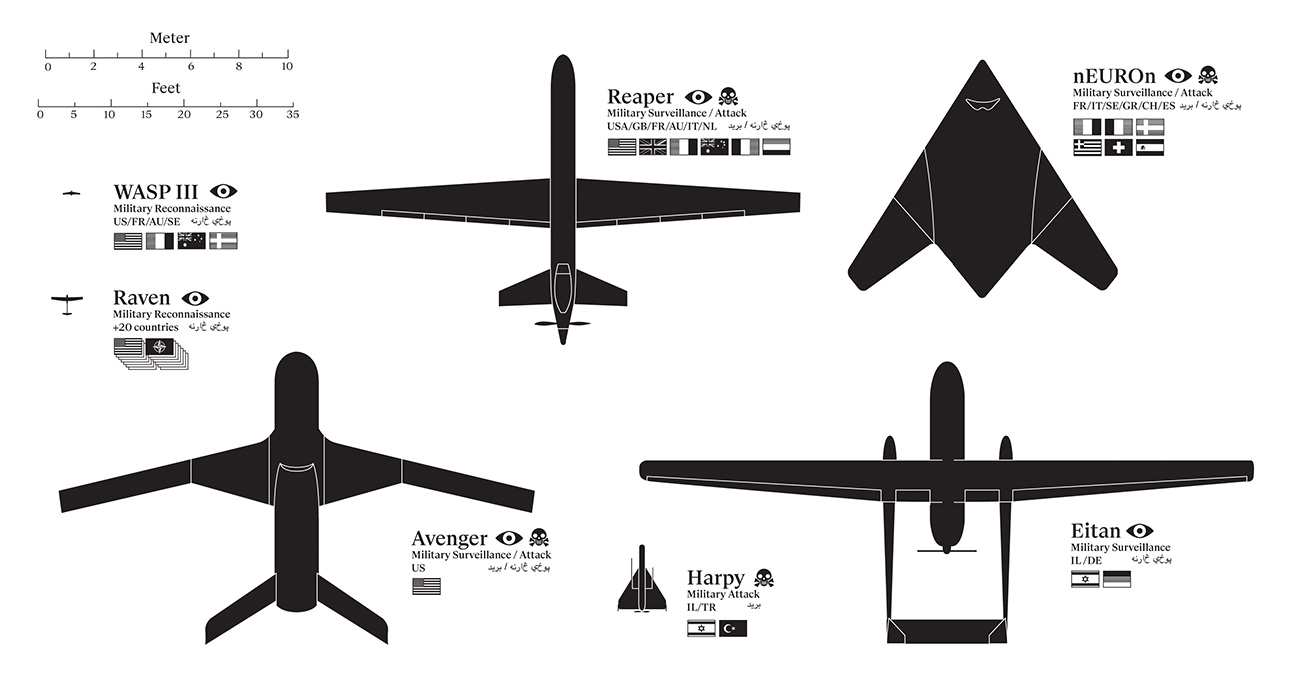

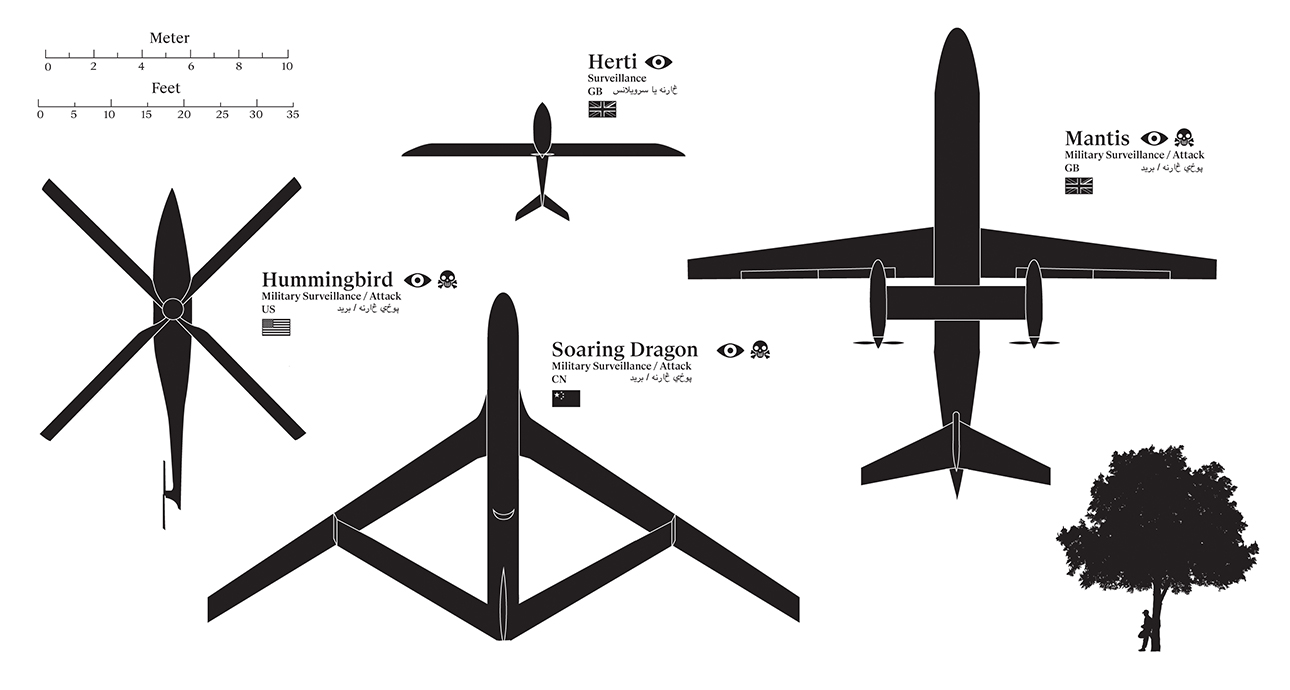

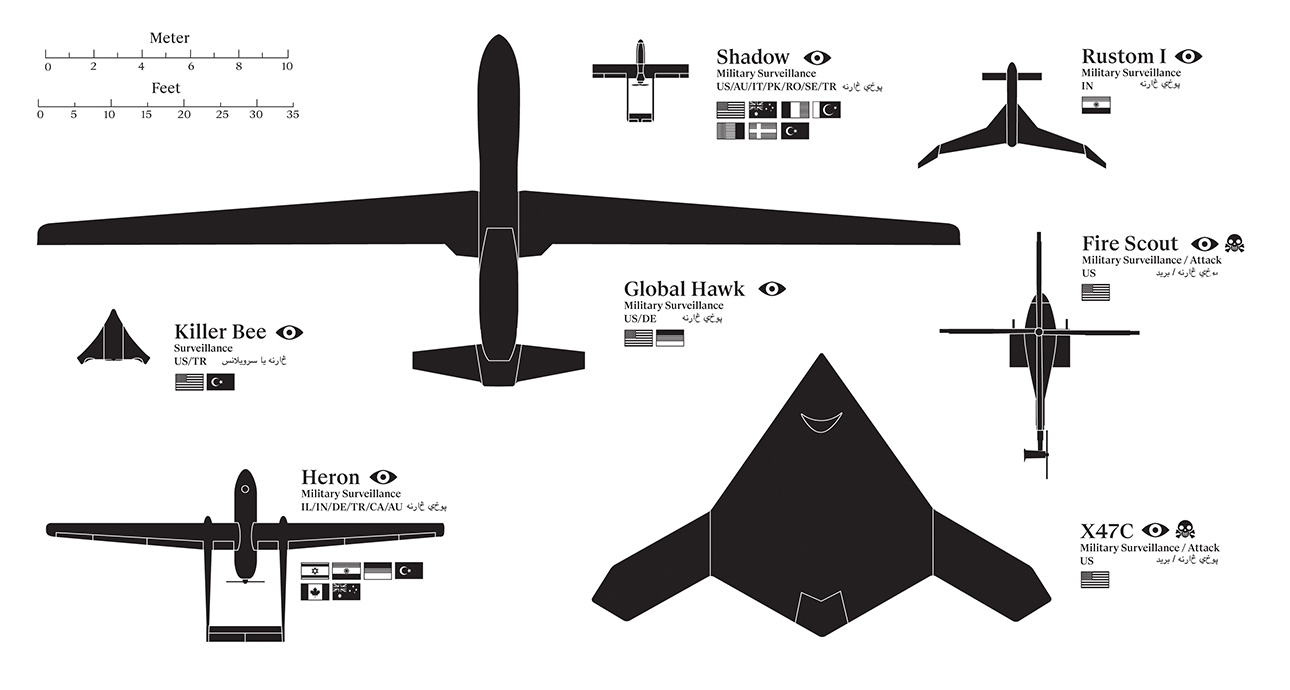

In 2012, Ruben Pater, a graphic designer from Amsterdam, created the Drone Survival Guide, a visual instruction on watching drones. In one poster Ruben gathered silhouettes of 27 widely used military drones along with annotations and tips for hiding from them. Among them – avoid using GPS, hide in the shade, and protect yourself from infrared vision with the help of heat blankets. The poster itself can serve as a heat blanket, because it is printed on a paper that reflects light.

Bird In Flight asked Ruben Pater about his guide, who needs it, how he was collecting all the information and why he decided to start working with drones.

Dutch designer. Bachelor of graphic design at St Joost Academy, Master of graphic design at the Sandberg Institute. Spent 10 years working in private international corporations. In 2012, launched Untold Stories, a design project dealing with complex geopolitical questions through a simple visual form. Teaches at The Royal Academy of the Arts at The Hague.

How can people use your “Drone Survival Guide” poster?

It is not a poster. It is more like a bird-watching guide, created in the form of a poster. Back in 2012, when I started my work on drones, the issue was mostly carried out in the realm of technical and very specific military and technical terms. Though it was already clear back then that it was a weapon of war, killing masses of people. I wanted to kind of debunk this issue and to make it something that everybody could talk about. That is when I came up with this “bird-watching”. Modern technologies have become our natural environment. This poster is a robotic bird-watching tool of the future, just like the one that ornithologists use while working in the wild. I printed it on Chromolux ALU-E paper that reflects light. The poster turned out to be quite compact — 48 on 33 cm, it can easily be folded and carried around in a pocket. One side of the poster has all the silhouettes of widely used military drones, each indicating whether it’s used for surveillance only or for military attacks as well. The flip side has various survival tips. Here I used simple graphics to explain how to hide from a drone, hack it and disconnect it from the pilot.

How practical is this guide?

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) predicted in 2012 that within 20 years there could be as many as 30,000 drones flying over U.S. soil alone. This sphere is developing very fast, but there is not so much information around. It was not my intention to make an actual survival guide. It’s more of an activist tool that has proved to be quite popular and has been translated into 20 languages, including Pashtu, Arabic and Russian. At the same time, it’s a reminder that many people around the world actually do need a survival guide. Sometimes I am asked to make new versions focusing on particular countries or regions. For example, I’ve just made one for South America, where I tried to look at the local context there.

I thought that this project would be interesting for civil activists only. But I was surprised to find out that it is also quite popular among military specialists. I think that’s a positive aspect for me that you can make a project that appeals to different sides and it’s not just adopted by the side that already agrees with you.

How did you collect all the information on drones?

A lot of the technical information is basically provided by the manufacturers. You can simply check their website and read all the specifications of different models online. The industry is large. People are buying and selling drones internationally. 85 countries in the world have drones. If technical information wasn’t available, I used techniques like Google Images photographs, and then based on the photographs, I tried to assess how large the drone is. Readers of Untold Stories have also helped me. In some instances, there were minor mistakes and people would email me and I would update the information. Ideally it would be nice to update the poster every year. But the rate at which the drones are being developed is so fast that it would be impossible to keep up with that.

You also have an audio project, Drone Acoustics. Is it connected to the Drone Survival Guide in any way?

Composer Gonçalo F. Cardoso and I were working on it together. He pointed out that sounds for the bird-watching metaphor are also very important. In areas of conflict, drones are flying so high that you cannot see them, but you can hear them very well. Imagine it was constantly circling around above your head. Some drones can stay in the air up to 7 hours and often they circle the same area, so that people will hear the same noise for hours. Our project is an aural investigation into the pervasive sounds of drones that turn out to be even more terrorising for people than silhouettes.

You are saying that your projects should not be seen as practical advice or as an act of propaganda. Why is it important to you?

Designers are communicating various stories to the world and they choose particular forms for each of them. The work of a designer is quite often complicit with the existing narrative. Problems occur when this narrative turns out to be part of explicit propaganda. Designers should be very aware of their position as mediators and translators. I think they have to be brave enough and be able to intervene. If they think that the message that they are asked to communicate might have a very explicit political or broader context, they can choose not to do it or to give it a different spin. I think designers have much more agency in that sense than they normally see themselves as. I think that designers often tend to trivialize their own profession making it kind of seem smaller and cuter. This is something that you don’t see in architects, for example. Graphic designers are people that can often say: “It’s just design, it’s just a nice poster”. Let’s talk about how it looks and about its concept, but let’s not make a big thing out of it. I think that’s kind of a shame, because I think there is a lot more to it. I personally take pride in my profession and I am ready to change the general attitude toward it.

New and best