“Our Artillery Went Silent. And Then the Russians Came”: A Fighter from Donbas Battalion Remembers Captivity and the War

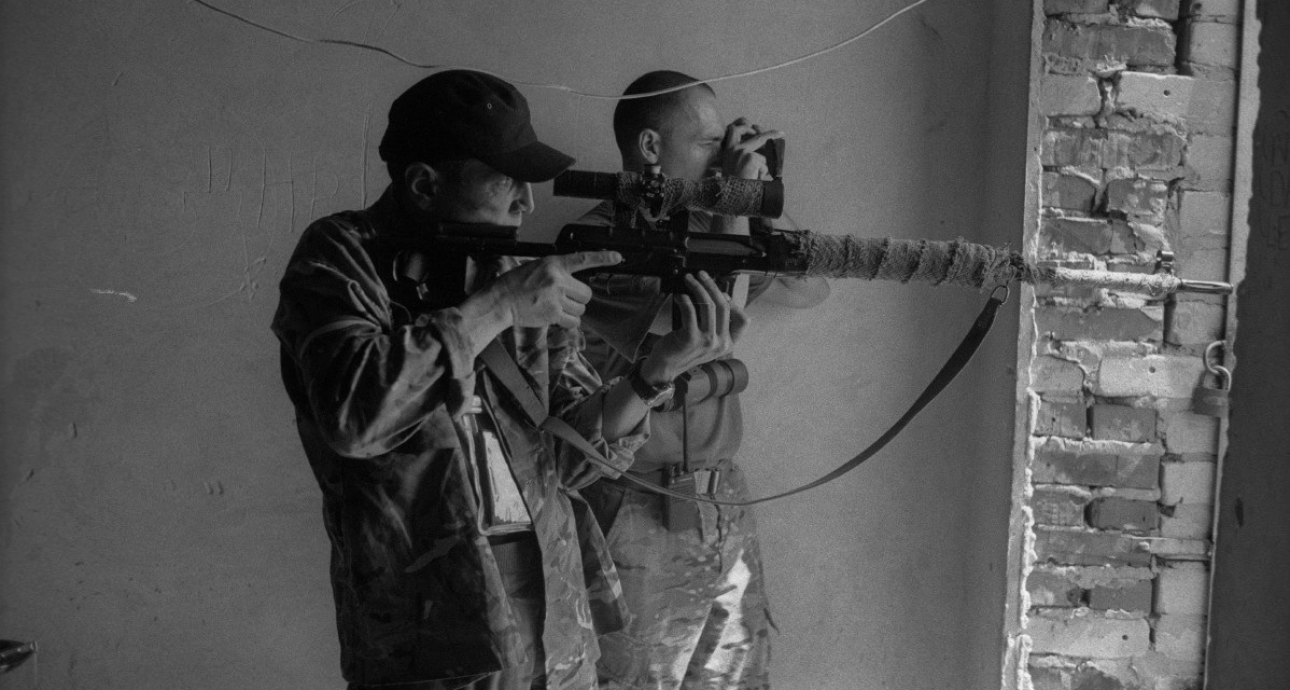

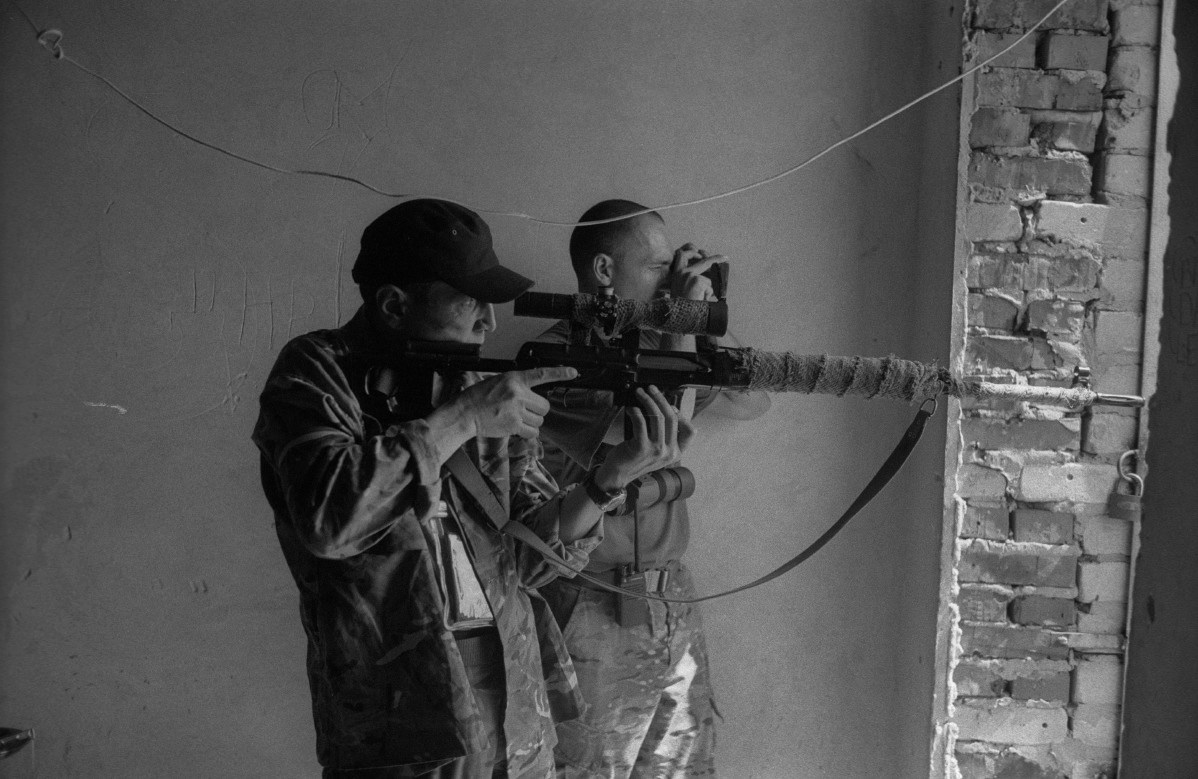

Maidan activists and patriotic people from the eastern part of Ukraine created the Donbas battalion in the period when the regular army and law enforcement agencies were time after time showing their weakness and lack of morale when encountering pro-Russian militants. The effort of poorly armed and poorly trained Donbas fighters helped liberate a number of cities and districts in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. The change in luck happened at Ilovaisk, where the volunteers had serious losses, and many of them were taken captive. Artem Khorunzhyi, a 35-year-old Kyiv-born participant of the Maidan protests and a sniper in the Donbas battalion, could return home only after four months. He spoke about his experience in his interview with Bird In Flight.

Were you 33 when you went to war?

I was 32. I turned 33 in captivity. I was a lawyer. I worked in a beautiful office on the 24th floor with a great view. My friends and I were having a lot of fun. After Maidan, we calmed down a little, despite what happened in Crimea and the clashes in Slovyansk. But the tension was growing, and things were becoming more serious. I watched people go straight from Maidan to the newly created National Guard. I couldn’t go to the conscription office myself as I am “unfit for service”. I have perfect vision in one eye, but I am almost blind in my other eye. My mom, my grandma have the same thing. I am an eye lefty.

What brought you to the decision to volunteer?

I saw the interview with Semenchenko, the commander-founder of the battalion, and that was how I found out about it. Standing there is his balaklava, he said that there are two parties in Ukraine: the party of patriots and the party of traitors. And we have to defeat the latter as soon as we can. He was eloquent. He said the right things with the appropriate intonations.

Did he say he was calling people to sign up for the volunteer battalion?

Not in that interview, no. But a week later, the Donbas battalion started to sign people up on Maidan Square. It was on the news and I read about it on Saturday. I took Sunday to think. And I realized I needed to go. On Monday I quit my dream job, on Tuesday I bade farewell to my huge and happy apartment, and on Wednesday morning I was in Petrivtsi. It was late May or early June 2014.

I couldn’t go to the conscription office myself as I am “unfit for service”. I have perfect vision in one eye, but I am almost blind in my other eye.

Do you mean the training camp of the National Guard?

Yes, a terrible place. When a young person finds themself in the army, the army needs to break them to send them to kill people. This is normal. The Western-type armies break you by exhausting physical exercise. And in Ukraine they do it by destroying your human dignity. Everything in the camp works in such a way so that the person would stop feeling human. There was a lack of tents. We stayed in a huge hangar. Everything is falling apart. Everything is terrible and rusty. No individual toilet cubicles. Instead of them, a hangar without partitions and holes in the floor. All of those grown-up men have to do it side by side… The sewage is poured into the trough that goes across the camp. There is a kitchen where they feed you… With what they probably feed to guard dogs in penal colonies. Fried canned fish with shortenings.

Petrivtsi was a base camp not only for the Donbas battalion, but also a unit of Internal Troops. The boys from Internal Troops were on the other side of the barricades during the Maidan protests. At first we pitied them, but the more encounters we had, the more we saw what was disgusting in them. We ended up losing our compassion. We called them give-me-a-cigarettes — they were constantly asking us for one.

How long was your training?

Only a month, we didn’t see much of a shooting range. Afterwards, we could feel it. Both us and our commanders made incorrect decisions in combat situations. But the entire Ukrainian army had this problem. Our strength was in that we volunteered, we wanted to defeat the enemy, to win. When the others were turning back, we were advancing.

What did the volunteers fight for?

Depends on the person. I thought about my grandfathers. One of them was an engineer in a factory in Kharkiv, and his factory was evacuated far behind the lines during WWII. He could go along, beyond the Ural Mountains, and continue to build his turbines. But instead he asked: “How would people look at me?” He died in the defense of Sevastopol. His words were passed from generation to generation. My other grandfather came back from the war alive, he was fighting in the Far East. These stories are told to the boys, and they mean a lot. I could not but go. There is a war in my country. I am a man. I have to.

So, after a month in Petrivtsi training camp you joined the fighting?

We went to Artemivsk [currently Bakhmut — Ed.]. The journey took two days, and everywhere we went people greeted us. Sometimes we stopped at gas stations, and they gave us cigarettes, food, and their smiles. Everyone was upset we were not there in time to take part in the liberation of Sloviansk. We were anxious to fight. In Artemivsk, “Philin”, the chief of staff, said that the town was government-controlled, but we needed to be careful because it was full of civilian separatists. On the first night, someone fired a machine gun at our position, and a grenade flew into our window. This kind of thing happened a lot. There was no contact line then. There was no ‘zero’.

What is ‘zero’ like?

Now it looks a lot like WWI — it’s trenches on trenches there. Zero, the neutral territory, starts beyond our trenches. There was no neutral territory back then. The trenches were few. We were reluctant to dig them, we did not know that trenches could save lives.

And then, there were the first deaths, inflicted by our own soldiers on our own soldiers. This happens in every war. This topic does not get a lot of coverage, but it happens always, even to the best armies in the world. The guys were coming back from a reconnaissance mission, they gave all the right passwords, but someone made a mistake. A round from a sub-machine gun, and that’s it. Two people died.

Do their relatives know the truth?

Of course not. It must be absolutely unbearable to find out that your son died at the hands of his brothers-in-arms. The families should never be told this. A person died in war. This is part of combat.

And then, there were the first deaths, inflicted by our own soldiers on our own soldiers. This happens in every war. The guys were coming back from a reconnaissance mission, they gave all the right passwords, but someone made a mistake. A round from a sub-machine gun, and that’s it.

What about your first battle?

We took part in the liberation of Popasna. We were going there in two columns, and the first one got in trouble — many guys were wounded and killed. I was with the other column, on the other side of the city. We got lost. You know, war is when the side that is 5% organized defeats the side that is 3% organized, everything else is very disordered. What has to break, will break. The maps you have will be wrong. You will definitely go lost. Things will go wrong.

The middle strip of Donbas is beautiful: nature, the fields, the rivers, the villages that drown in cherry blossom, even the gob piles are beautiful. There was an unharvested field of sunflower on the right, and a field of overripe wheat on the left. We stopped to snack on our terrible dry rations — who makes rations for our army? — and then we heard the guns, a unit of shock troops attacking them, crackling, sound coming over the comms, someone wounded, someone killed. And we are there in the field with a bumblebee flying around us. I was thinking: “I have to remember it all.”

We eventually found the way and arrived on the other side of Popasna. We immediately took over a checkpoint. Shooting, bullets whistling by. The first dead person I saw was not ours.

How long was Popasna under the DPR [unrecognized ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’], non-government-controlled?

For about a month. But it was only relatively so. Ukrainian state agencies and banks were working, taxes were paid to Ukraine. But the DPR militants took over the city council and the local office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and hung their flag there. They were walking around with weapons. This was surreal. We stopped two guys in a car, the covered in the ribbons of St. George kind. And they turned out to be our neighbors from Petrivtsi training camp, only they went to fight for the so-called DPR from there. They were on their way to get munitions in the neighboring village. They ran into us accidentally.

Were you in that village on a recon mission?

Yes. We went in on two mini-buses and started asking around. A usual site: a village, an unpaved road, men drinking on a bench. Women scolding them. We are asking them what’s what. And then we realize that we’re trapped. We see people in uniforms coming at us from both sides. We jumped into the buses — my sniper’s spot was in the back, near the open back door. We were ambushed, they started shooting at us. We were firing back from all the windows and guns. I even reloaded mine a couple times. I don’t know how I didn’t fall out.

How did you become a sniper when you’re almost blind in one eye?

My other eye is very sharp though. By that time, all the other units were manned — the grenade throwers, the shock troops — but not the snipers. It was my first time to ever have a sniper rifle in my arms, I hit the shooting range targets. They told me: “We are waiting for you!”

Did you hit anyone in your first fight?

You just don’t know this, you never do. Besides, I was wounded. A bullet came through an open door, ripped out a piece of metal from the car, it hit the artery in my shoulder. There was a fountain of blood, but no pain. We got out alright, everyone was alive and nobody got seriously wounded. On that day I realized that it is not only in action movies that people can survive under crazy gunfire. This really happens. It is hard to hit a person.

You know, war is when the side that is 5% organized defeats the side that is 3% organized, everything else is very disordered. What has to break, will break. The maps you have will be wrong. You will definitely go lost. Things will go wrong.

Is that piece of metal still there?

The piece of metal is still there. They told me in the hospital in Artemivsk that they could take it out, but they would have to disassemble half of my shoulder, and it would take a year to heal. I told them I did not come there for this, “bandage it.” Two shots of antibiotics — I needed to have more, but my body fought the infection on its own. This was my first wound.

Later we took Popasna without blood — the militants just ran away. And later Lysychansk. We had to fight for it, and it was covered in the dead bodies of the militants. It was then that we realized we were not good for nothing. The marines and the infantry from the regular army thanked us, as they had rarely seen people who would throw themselves into battle with such gusto. Then we hit a wall with Pervomaisk. Then there were Kurakhove, Marinka, and the first and second attempts at taking Ilovaisk.

The second attempt at taking Ilovaisk and your second wound?

There was no frontline, just friendly troops and the enemy everywhere. We had a flat tire. Stopped in the yard to change it, but we heard loud voices. We separated, two sniper pairs. Just two sub-machine guns, you can’t use a sniper rifle at a 10m distance. I took a position near the entrance to the yard, behind the rail that holds the fence together. I can’t forget it… A young guy is sneaking along the fence. At the crossroads, the street light uncovers him. And I am in the shadows, he doesn’t see me. I start shooting at him. Our Valik starts, too. We were shooting, and the two other guys were throwing grenades behind the fence.

Was it your first close-in combat?

Before that I never shot at anyone from three meters. At some point shrapnel cut my face, blood started running, I started losing my grip on the gun. It was dark outside. I was half-blind — we were blinded by our own shooting. After I shot two magazines, I realized I needed to move. I joined the guys. We heard “Grenade!” and thought it was flying at us. My life passed in front of my eyes. And then, nothing happened. Everything went quiet. Then we knew it was our Yura who threw it. That grenade must have been a decisive one. We killed them all.

How many were there?

More than six, I don’t know more exactly.

It’s funny that after that we went to get our commander. We accidentally left him in Starobesheve after a meeting, the column left while he went to the shop. You see how surreal it was? He hid himself and saw how at night a regular Ukrainian town turns into a separatists’ stronghold. The day after that we went to Marinka, which is very close to Donetsk. I spent a night inside a shell crater there. The sky was lit up as if it were Las Vegas, by Grad missiles, shells, and fires.

I can’t forget it… A young guy is sneaking along the fence. At the crossroads, the street light uncovers him. And I am in the shadows, he doesn’t see me. I start shooting at him.

How many sleepless nights did you have before Ilovaisk?

Three. There is such a cocktail of hormones in your bloodstream that you don’t want to sleep. I slept already in Grabske. It is a small village in the suburbs of Ilovaisk. The villagers abandoned it. Covered in dead bodies, burnt equipment, infantry vehicles. I saw the infantrymen of the 93rd brigade for the first time then. They looked like migrant workers on a construction site. Dressed in rags. Cleaned their SMGs with god-knows-what.

Are we talking the regular army?

Yes. It was a group of ragamuffins under the command of a 24-year-old boy. I have to say he looked absolutely brilliant amidst it all, he later fought in Ilovaisk and stayed alive. And all of the equipment of these guys, the 93th brigade, burnt down. Many died.

Grabske was nobody’s. We cleared it. The village ended with railroad tracks. And a green field behind it, that we needed to go through to understand the situation. I had to do it. I remember crawling in total silence. I could hear every valve in my heart.

But you’re not a scout, are you?

Neither of us was a scout, but someone had to check that field. There was nothing there. But it was then that I got the most scared.

Was that July?

August, August already. It smelled of dead bodies — you can’t get used to this smell, can’t get rid of it, it smells like nothing else. In the summer, it takes only so long for the bodies to inflate and explode.

Were those the bodies of the DPR militants? They didn’t collect them?

Sometimes they did, sometimes they couldn’t do it. See, in the summer of 2014 they died in heaps, nobody counted. They were hit by artillery fire. They died in terrible numbers. I did not see many dead people before that. And there — the first body I saw had a hole in his chest. The second — had a ruined skull, with only a bit of face with two crazed eyes left.

Do you remember all of it?

Yes, but I want to tell you it does not touch you. You look at awful things and nothing happens. You were shooting at someone, you would think it would change something. But nothing happens to you. I don’t know what to think about it. I was lucky to have a psyche that was not easily penetrated by those things. People with their legs ripped off, burnt people, burning people, with mangled groins, the insides outside their bodies — none of it was surprising or irritating, it didn’t cause dread or fear. We did feel pity for the animals though, who were bound to die because their owners fled. There were many dogs, cats, geese, chickens, and cows. They were used to having people feed them and take care of them. They meowed and barked, and looked at us with sad eyes.

How many enemies did you kill?

I don’t know. I just don’t know if I killed anyone at all. I don’t have an answer to this question.

Did everyone in your snipers’ four survive?

Liokha was the only one who died in my platoon. It was for some reason a father of three children who had to die. When we were getting out of Ilovaisk. The snipers’ platoon turned out to be the most die hard.

How did Ilovaisk start for you? Tell us your own story.

Ilovaisk was half-encircled, it was a strategic location that we needed to take. We tried three times. First was the reconnaissance in force that cost us a couple of painful deaths. The second time we arrived at our positions and waited for the command to advance, but everything got canceled. The third attempt was the best planned operation I remember. It was well-thought out, not just the usual for the summer 2014 “those trenches and dugouts there down the road, take them.”

We went around Ilovaisk from Grabske and entered the city from the side where nobody expected us to. In the evening, we took the school. I was one of the first to go into the basement. And there were people hiding there. We ran for some food to give them, shared our dry rations. Several dozen people were sitting in a small basement for several weeks — with children and kittens. They were happy to see us. We took half of the city, which completed our half of a mission. “We” means Donbas battalion with 4 infantry vehicles and the 93rd brigade. The other guys had to take the rest. But they failed.

Ilovaisk is one big freight station. The city is divided in two by the railroad. We went over the tracks instead of those guys. There was heavy fighting that lasted the whole day. We lost many people. I remember when we sought cover behind a fence, and a puppy with a bow turned up. We are in the middle of a fight, and he’s playing with my shoelaces. He must have gotten used to the shelling…

How many days did it last?

Ten days of daily street fighting.

Were you fighting for full liberation of the city?

After day two it became clear that we will not be able to take the other part of the city. We didn’t know anymore what we were doing there. Our artillery went silent. And then the Russians came. They were not the first Russians, but this time they were Russian soldiers on Russian tanks with Russian insignias and Russian military IDs. We captured the first ones nearby, in Kuteynykove. Our recon guys found them, captured them and returned to tell us about the column that was moving at us. Artillerymen from the 51st brigade, those heroes, destroyed that column. Then we captured a tank crew. We captured a Russian T-72. We used it when we retreated from Ilovaisk.

I don’t know. I just don’t know if I killed anyone at all. I don’t have an answer to this question.

Was the Savur-Mohyla defensive done by then?

Even a bit earlier. When we were heading towards Ilovaisk for the second time, we met the artillerymen who got out from under Savur-Mohyla after a week of fighting without any infantry support. I remember that the column stopped at a shop. A colonel came out with a bottle of vodka and drank it all right there. They were going out, we were going in. He said: “Guys, we can turn around and go where you want us. We have munitions. It’s just that we were stationed alone there, everybody must have forgotten about us.”

Savur-Mohyla, Amvrosiivka. The Russians turned up, there were many of them. Then our artillery disappeared. We lost support. We realized we were encircled. We were being told that help was coming-coming-coming. The help was shot at, as we found out later, and it was so small in number that they couldn’t have helped us. The troops positioned under Starobesheve and Kuteynykove had left, but nobody gave us an order to retreat. Many thought about this as “volunteers being betrayed.”

Do you agree?

What can be explained by mere stupidity, shouldn’t be explained by conspiracy. Not only the volunteers were there, the army units, too: 93rd, 51th brigades, 17th tank brigade. We were ordered to “Hold on!”, and we did. And then Putin said: “Make a green corridor!” I have no idea why anyone believed it. We were not ordered to fight our way through. It was sort of an agreement that we surrender the city and they let us out, and we give the Russians their captives instead.

There were almost no vehicles left. We were leaving on fire trucks, motorollers, anything. When we formed a column, mortar shelling started, shells were falling 600m from us. The column reached Mnohopillia — and we’re hit again and again. The column was destroyed, cars were turning to dust one after another. And people in them, too. Some have no arms, some have no legs, someone is burning. We saw how heads burst when they are hit by large-caliber bullets.

Despite losing 40 people and having many wounded soldiers, Donbas battalion found the ambush where the shooting came from. Our grenade throwers burned down two tanks and two infantry vehicles. We killed many Russians and captured some more. Unfortunately, almost all of our commanders died on that day.

Did you know they were Russians from their documents?

There is even a video with their interrogation on YouTube. It was horrible, the shelling didn’t stop, the wounded were screaming. So many walking dead, who were fatally wounded, but kept walking. I remember one Russian marine: all of his body was burnt, he screamed terribly. We wanted to shoot him, but the paramedic injected him with a large dose of painkillers, and he fell asleep.

Was this marine a POW? Were there other POWs in the column?

Yes. The Russians were shooting at their own soldiers. And they knew that there were their guys in the column. One of the first shells hit the car with our wounded. A big car with a big red cross on it.

Do you know how many people died?

There are still no official statistics on it. We think about a thousand people.

How did they capture you?

In the evening two trucks with Russian marines and their commander “Lisa” (“Fox”) approached our position. We gave them the POWs. It was a weird arrangement. We agreed that we were leaving without weapons. They promised to take our 80 wounded people to Komsomolske (currently Kalmiuske) and pass them on to our troops. Many left at night: some survived, some didn’t. But our commanders decided we were not going to leave the wounded behind.

In the evening two trucks with Russian marines and their commander “Lisa” (“Fox”) approached our position. We gave them the POWs. It was a weird arrangement. We agreed that we were leaving without weapons.

Were you hoping it would be okay?

We were expecting the arrangements to be fulfilled. Most importantly, we were made a promise that we would not end up in DPR captivity. The commander of the marines said with pathos: “I give you my word as a marine, as a Russian officer that you will not be captured by the separatists.” But after they let go the conscripts from the Kryvbas battalion, there was just us in the field, and we were approached by a vehicle column. They turned out to be the separatists. It was a shock. Nothing to do, but just to survive.

On the way to Donetsk I took my chevron off. It wasn’t them who put it there, it wasn’t theirs to rip off. We were taken to the inside yard of the Donetsk Security Service building. The funny crowd gathered around us immediately, they were like monkeys. Their leader was saying that it was Miner’s Day, and he used to be awfully drunk on that day in previous years. There was a man who kept saying: “I love Ukraine, I am for Ukraine. But how the hell could you come here?” We were filmed. I remember I ordered myself to look straight and not argue. But there was one separatist who dragged me into a conversation. I started a dialogue, he hit me several times in my face and stomach. He was a big, 100kg guy, but he hit like a girl. I had to wince to pretend it hurt.

Then, they took us to the basement, a former bomb shelter. When you walked in, they shot you with a non-lethal handgun. Many were shot in their backs, faces, chests. A couple people could take those steel balls out only when they got out.

What was your prison like?

The basement had five or six rooms, which formerly had the infrastructure necessary to survive through a nuclear winter. Some sort of a ventilation system. A toilet and sinks — those didn’t work very well. Several wooden bunk beds. We had one for five people. It was hard to sleep, all the time something goes numb or hurts. Every night another separatist broke in “to talk.’ But the most difficult were hunger and stories like “We will shoot you, nobody cares about you!” It dwelled on you. “Nobody is going to exchange you. We offered, but your side refused.” And again, “We will shoot you, we will shoot all of you.”

The hunger was grave. We got peeled or pearl barley porridge, once or twice a day. Or they brought us soup with just two potatoes swimming in it. And a small piece of bread. You woke up thinking about food, and spent the day with this thought. And after you ate, you were extremely hungry again after 40 minutes.

Were you interrogated?

During my first interrogation I said that I was a conscript.

They didn’t know you were a volunteer?

It’s still a mystery to me. All of us told them we were conscripted. I said that I was sent to Petrivtsi near Kyiv. That I was going to spend a month guarding the checkpoints and go home. My interrogation lasted three minutes. They asked me: “Did you shoot?” I said: “Do I look like I could?” I could never re-play that intonation again, I could get an Oscar for it.

They allowed me to call home.

Did you ask them to?

No, they offered it themselves. I was not sure it was the right thing to do. I was afraid they would start blackmailing my family. But then I decided: I’ll call my mom, she’s smart. I called her, I told her that I was in Donetsk and I still had my legs and arms, everything was fine. My mom said: “Artem, we’re doing everything to get you out of there.” It was a short conversation.

Every night another separatist broke in “to talk.’ But the most difficult were hunger and stories like “We will shoot you, nobody cares about you!”

How did you kill time?

First Kolia and I made cards from cigarette packs. Later we had backgammon, checkers, and chess. There was a preferans club. We had dice made from bread, they were hard.

From time to time they sent us to the works. From there we could bring back some books. As if in a cheap movie, the first book in the basement was the iconic Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar. It’s hard to read, I gave it up pretty soon. Then, there were other books. And some newspapers and magazines. But when we started lacking cigarettes, people smoked books.

How many people were there in the basement?

106 people at first. Later 10 or 12 of them were exchanged, for those separatists whom we captured in Ilovaisk. I think it helped save our lives. When they came back from our captivity, they said they were given food and water, and shelter during shelling. It is not that they stopped torturing us after that exchange, but they must have decided they were not going to kill us.

Then we had a parcel: cigarettes, tea, and for some reason, candy. I didn’t smoke, so I got not one, but one and a half candies. There were only two parcels in all my time in the basement. I had three drop sweets from the second one. There were people who ate them slowly for four days. I ate them all at once.

Also, there were traitors. “Kaplan” — he was responsible for the medicine cabinet. He was ratting on us, told them everything about us. Then, there was Mikha. Because of them, some of the guys were beaten. I don’t know why these two escaped punishment [when we got out]. Kaplan only got a couple of blows.

Where are they now?

I don’t know where Kaplan is. Mikha has a successful Facebook page, he is at the frontline somewhere, he is friends with many volunteers. And that’s taking into account that we testified about them to the Security Service of Ukraine.

How did you get out of the basement?

In a couple months 66 people were taken to Ilovaisk to do the restoration works. We spent two and a half months there. They put us in the garage, then in the Ilovaisk commandant’s office, a former police department. The rest of the time we lived in a burnt two-storey house. We made furniture from shell boxes. There were no windows. We had a solid fuel stove.

What kind of work did you do?

At first we collected bricks from a shed that was destroyed by a mine. Then we were sent to the Culture House to unload a truck of weird secondhand stuff from Slovakia.

I saw you on tape twice. Once in the yard of the Security Service building in Donetsk. The other time when you were unloading those trucks.

We could barely stand up straight, we’ve been unloading that secondhand stuff for four hours. Each of us received a loaf of bread as a payment for our work that day. Then, Russian TV came. They asked us if it’s right that the Ukrainian army was shelling civilians, killing women and children. Our answers were evasive. I remember the last question they asked me: “Despite what you saw and went through, do you still think you did the right thing?” Although our battalion got a lot of media coverage, we were hated more than the others, those journalists didn’t realize we were volunteers.

I repeated again that I took an oath, I was just a soldier who followed orders. Then one of the separatists took me out to the street and put me against the wall. I heard him take the safety off, I heard the trigger click and two shots above my ear. A journalist ran out of the building, got into the car together with her crew and left. Their goal was to scare me and make me give the right answers. But I don’t think the journalists were ready to see me shot.

One of the separatists took me out to the street and put me against the wall. I heard him take the safety off, I heard the trigger click and two shots above my ear.

Was every day like this?

There was an unpleasant moment when they sent us to collect the shells and mines near Kuteynykove — they found a field artillery warehouse there. It could blow up any minute, but it didn’t.

Then things started going smoothly. Nothing good happened, we just got used to it all. Some people were beaten, but not too often. From time to time the commandant’s office was taken over by visitors from either Chechnya or Ossetia, it put us in mortal danger. Sometimes the guest stars threatened to cut our fingers off, like it happened to the marines in Snizhne. But again, everything was fine.

I worked in a building in the city center. Hairdresser’s, welfare offices on the first floor, a library on the second, a music school on the third. We were repairing the roof and the windows. We made friends with the employees. Can you imagine what the life of an Ilovaisk librarian is like? And here people are asking them for books and addressing them politely, unlike what they are used to.

It was a strange thing to internalize: we are captives, but there is a regular Ukrainian city around us. Some people are aggressive, but some help. They sent us food and clothes. One woman was walking past us and cursing us as hard as she could, but later brought us pies. It turned out her son was in captivity on our side. There were people who whispered: “We love you, we are waiting for your return.”

One woman was walking past us and cursing us as hard as she could, but later brought us pies. It turned out her son was in captivity on our side.

Did you think about escaping?

We could escape any day. Kill everyone in the commandant’s office, take the weapons, make some noise. There were 60 of us, which is two platoons. But then the fate of those 25 people who remained in the basement in Donetsk… It would have been very sad.

How did you find out about the exchange?

I was cutting glass for the windows on the first floor. The separatists came: “You have five minutes to pack.” Women from the library and the music school started crying: “Come visit us.” They gave us candy for the trip.

There was no happiness during the exchange, just enormous fatigue. The Alpha special unit guys helped us onto the buses. I called my Olia, it was her birthday. This, too, was like a cheap movie. The trip to Chuhuyiv was long, there we boarded an IL-76. When the gate opened, the President was waiting for us in the spotlight. It was a right step. Many of us thought badly of him, many hated him, but after all, who else had to meet us if not him?

We beat Kaplan, the traitor, right there. But then we thought we can’t do it with people looking, so we stopped quickly.

When were you released?

December 27, 2014.

When were you captured?

August 30.

Four months?

Yes.

New and best