The Early Days of Soviet Propaganda

Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels once claimed that he could turn any nation into a herd of pigs if he had control over the media, and that the main enemy of propaganda was intellectualism. Several years before that the Bolsheviks had proven his claims. In time, propaganda had turned many hesitating people to the Soviet side, which eventually decided the outcome of the civil war.

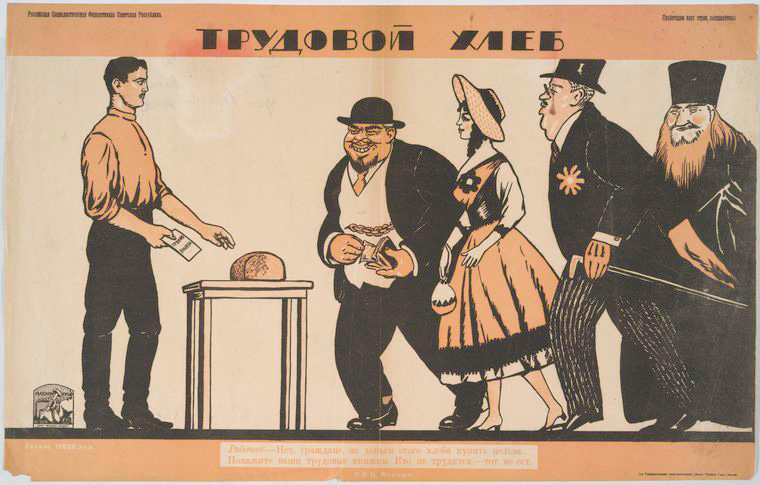

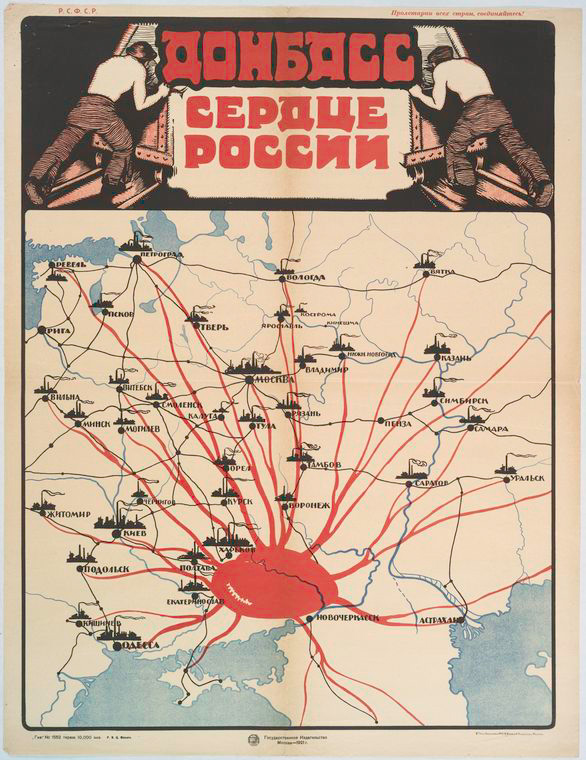

The Bolsheviks overthrew the authorities, but could not gather all the power in their hands all at once. They had the White Guard advancing on them simultaneously on several fronts, and they needed to quickly mobilize the pro-Soviet population. This was a tricky task, as they were not very good at ruling the country: there was hunger and lack of consumer goods, goods were distributed through a rationing system, and the shops were empty.

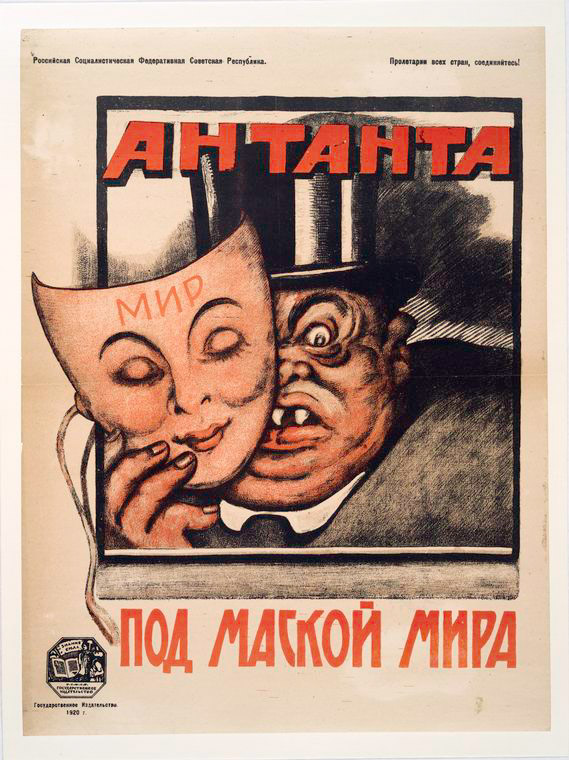

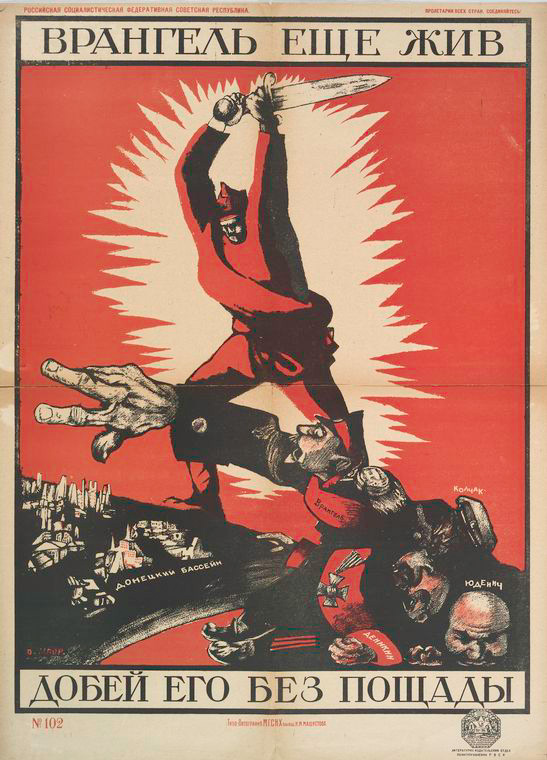

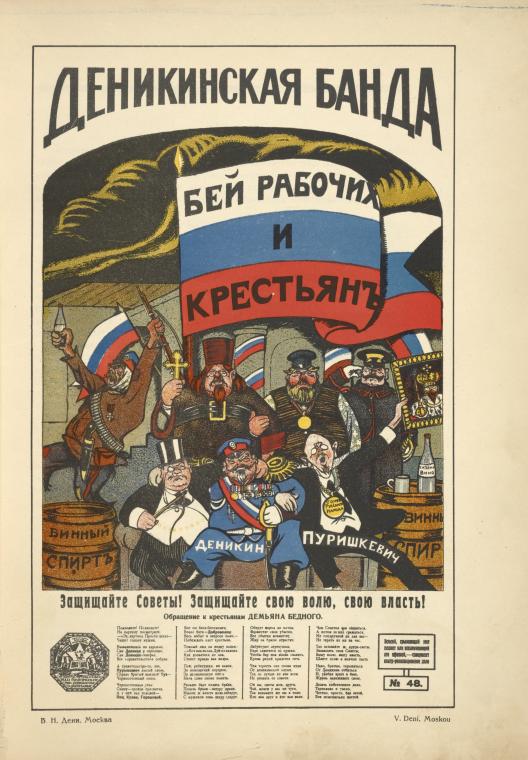

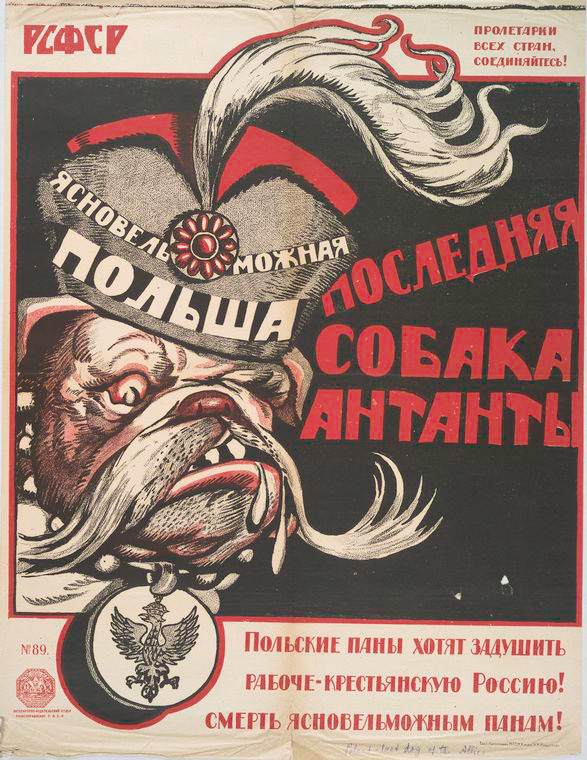

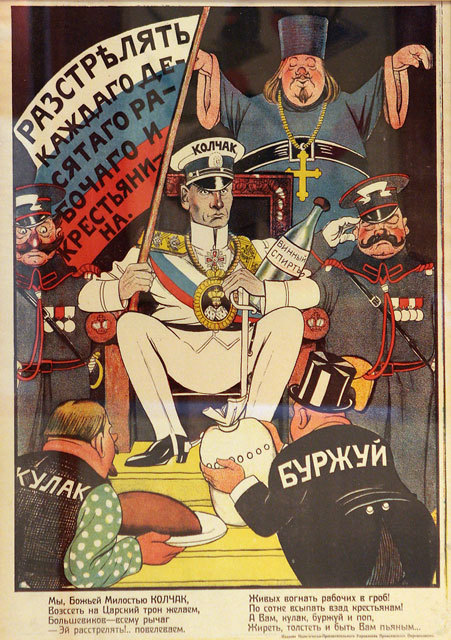

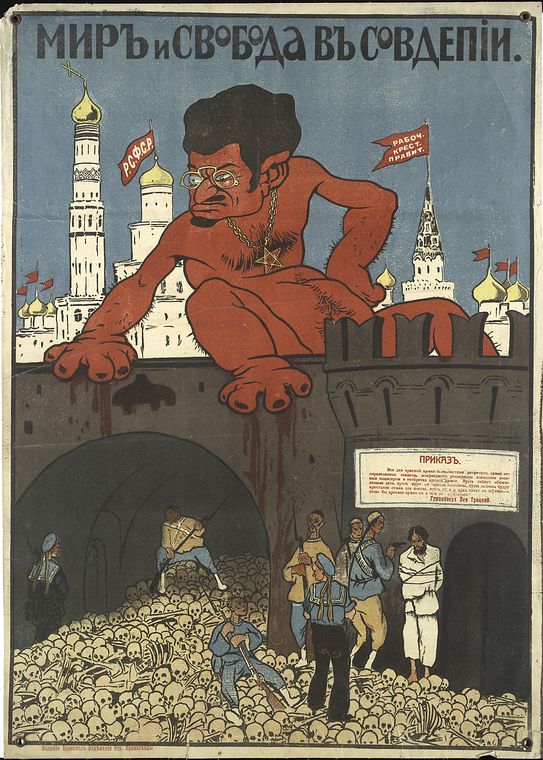

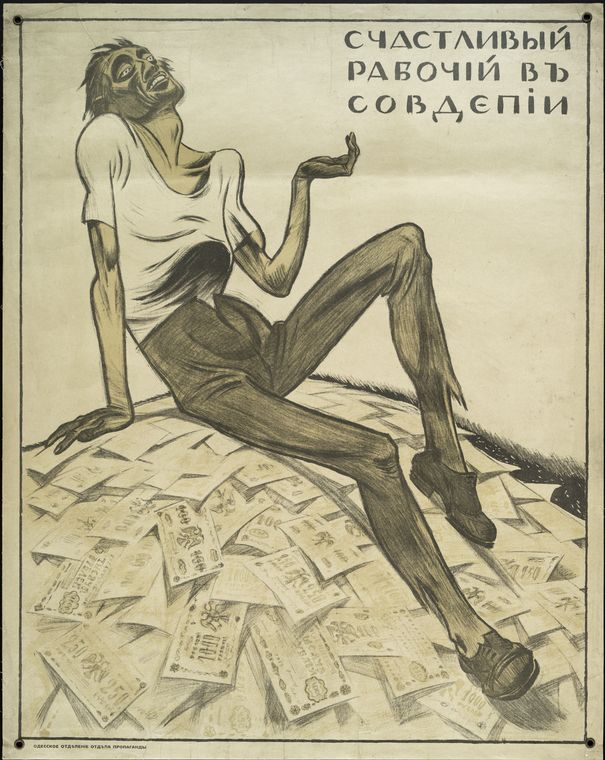

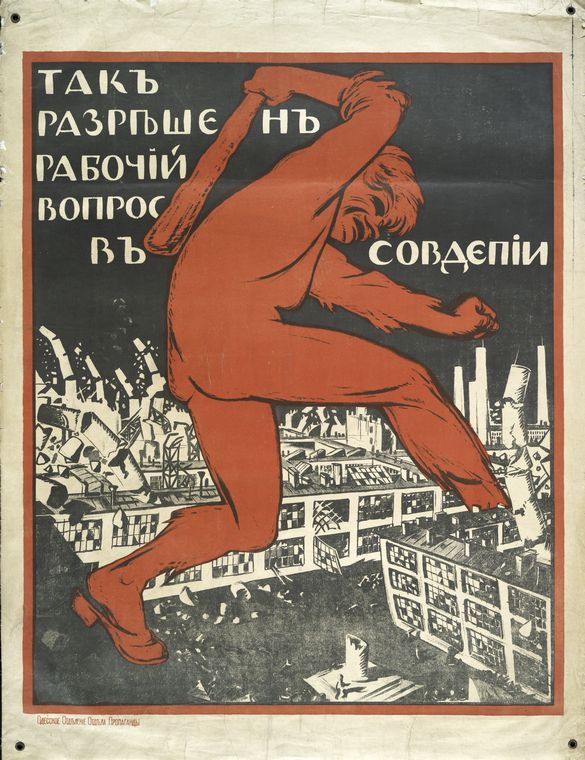

Only powerful propaganda and the search for enemies could distract a poor population from the internal problems. It turned out that badly educated peasants and workers were easy to deceive, and Soviet campaigning would be very popular among them. Soviet artists keep asking people to kill the enemies, be those officers Vrangel and Denikin personally or someone else, painted the Entente that sympathized the White as an unpleasant two-faced person, and said that the landowners, priests, and White Guard officers were guilty of all troubles.

The story of Soviet propaganda starts from Kuznetsky Most street, which in the times of the empire was the center of Moscow social life. The shop windows of this street, and later other central streets as well, were plastered with Soviet posters, and although the first works were not far from handmade, they quickly found its audience. The Bolsheviks understood very well the needs of the people and the language that people hear. The first Soviet posters were created at the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) and placed in the empty shop windows, hence the name ‘ROSTA windows of satire’.

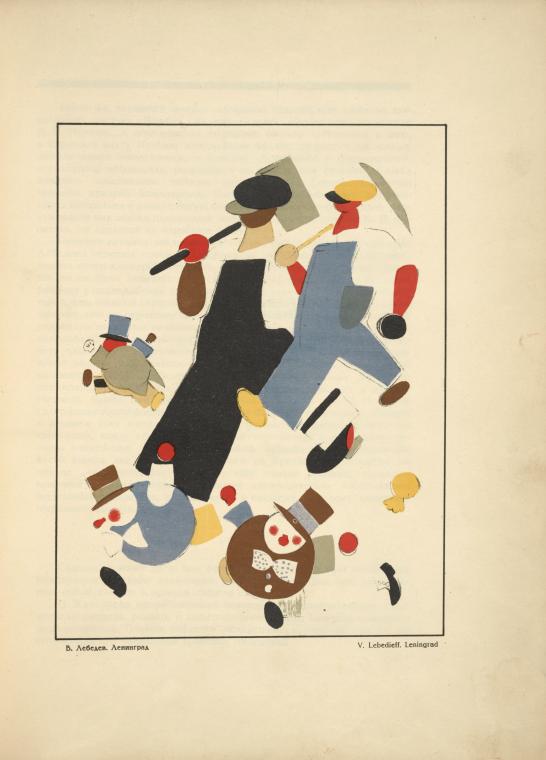

Soviet propaganda, unlike that of its enemies (the White movement had taken propaganda efforts of its own), was not aimed at the gradual settlement of the conflict. The posters called for fighting the enemy till the last drop of blood. The Soviet authorities were clear about being ready to eliminate everyone who would disagree with them. It became clear with time that the Bolsheviks have used Russian avantgarde to popularize their rather seditious and inhumane ideas.

At first, the Soviets managed to recruit prominent cultural figures, among them poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, artists Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky, cartoonists Viktor Deni and Dmitry Moor. For instance, Moor’s poster “Did you volunteer?” has become such an inseparable part of the mass culture that it is still a symbol of the epoch and the most recognizable work of Soviet propaganda.

The successful military campaign of the Whites in Siberia and in the south of the former empire gave them reason to launch their own propaganda. The White Movement established its own Information Agency (OSVAG), which cost them 25 million roubles in only one year. However, their problems started with trying to identify their audience. For the Bolsheviks, it was a peasant or a worker resentful against the imperial authorities. Who was the White propaganda addressed to was a mystery even to its authors.

Besides, the progressive part of the society was not excited about the attachment the Whites felt to the past. When White Guard officers took Kharkiv, they made Russian a state language again, banned Ukrainian as the language of education in state schools, and called Ukraine Malorossiya (“Little Russia”). The key mistake of the White propaganda was the wish to expand its audience by addressing the anti-Semitic sentiment. The pogroms against the Jews started happening more frequently in the territories controlled by the Whites. Of course, in this situation both the Jewish population and people who vehemently opposed such methods sided with the Bolsheviks.

When the White army lost positions, the White propaganda also declined. At first, the printing of color posters was moved to provincial and frontline typographies, but eventually they were replaced by easy-to-make informational bulletins and leaflets. In this form, OSVAG propaganda could not compete with the powerful surge of Soviet propaganda and gradually died away.

First, the White Army lost Kharkiv, then Denikin left the position as the Commander-in-Chief after a series of military failures, disbanding OSVAG, and in November 1920 the ships of the Volunteer Army have left Crimea — the last outpost of the Whites in the European part of Russia. Abroad, White emigrants continued to publish magazines and propaganda leaflets, but they could not reach their compatriots inside Soviet Russia anymore. Now their audience was reduced to the likeminded emigrants and was much smaller. Meanwhile, all power in the territory of the former Russian empire was concentrated in the hands of the Bolsheviks.

New and best