In the Cold Light of Day: How Architecture Defeats Heat

In the 20th century, architects often experimented with new approaches to building design and construction. Among other things, they looked into the experience of the peoples living in hot countries in a perpetual struggle with high temperatures and adapted it to modern times.

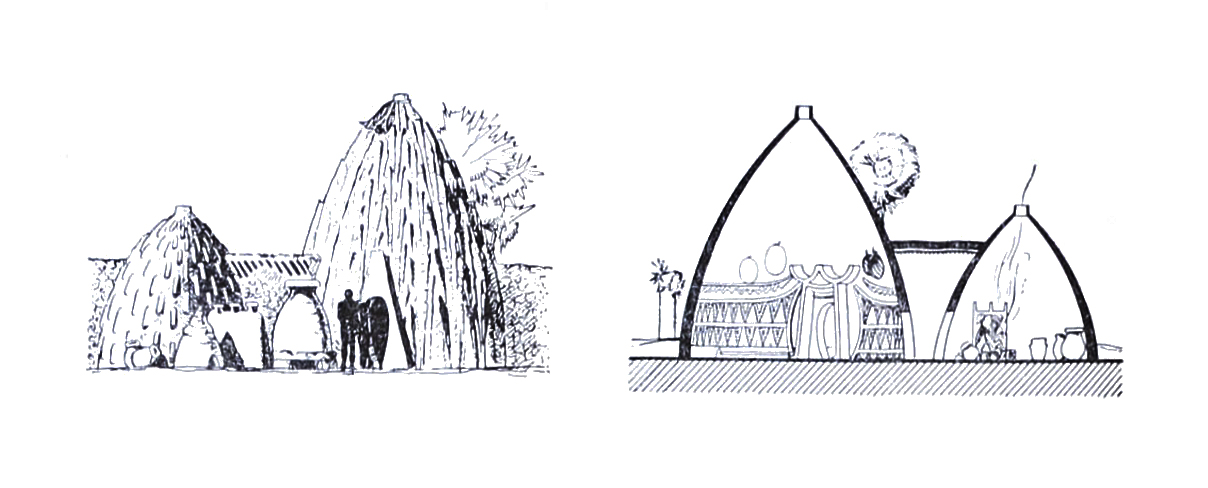

For instance, dwellings in Papua New Guinea were raised on stilts over the ground, which created a cooling air cushion. And the method of building houses according to cardinal directions was invented back in Ancient Egypt. There were also dwellings carved in cliffs, huts with openings letting out hot air, or broad eaves — in traditional dwellings of West Africa and West India. People also used ventilation shafts with water sprayers or wet woven wood shields over windows.

Let’s look at the most popular architectural methods used to cool buildings today.

A model of a house for sleeping and a kitchen: exterior and interior views

Orientation and planning

Le Corbusier was the first architect to start lifting buildings on supporting structures, leaving the ground floor free. He wanted the buildings to be spacious enough for people to move without restraint and needed the yards to “breathe.” Underneath such houses were cool spaces with green areas for adults to rest and children to play. It turned out that the buildings planned this way cooled down faster due to air circulation.

In hot countries, air ducts were arranged not only at the bottom of a building but also throughout it. This was achieved by leaving entire floors empty or adding separate open-sided cuts, similar to those in the Pedregulho Housing Complex by the architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy.

Unité d'habitation (1947–1952), Marseilles, France. Architect: Le Corbusier. Photo: Depositphotos

Pedregulho Housing Complex (1948–1951), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Architect: Affonso Eduardo Reidy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The houses themselves were built as long, narrow rectangular blocks. Their end walls faced the southwest, which is the side where the sun is hottest. And the facades with windows of apartments, especially those facing only one side, were directed to the east, the south, and the west (the buildings usually did not face the north to have enough sunlight).

Designers allowed for loggias in each apartment and entrances, providing access to fresh air and at the same protection from direct sunlight. Sometimes, loggias themselves would be decorated with panels that added shade.

Pivnichno-Brovarskyi masyv (1965–1975), Kyiv. Photo taken from the northwest. Architects: I. Shilin, S. Vainstein, A. Zavarov, V. Yezhov, and others. Photo: Mykola Kozlovskyi

“The Houses With Sails.” Photo: “Prydniprovskyi Barvinok” #barvinok_archive

In public buildings, more open spaces were created, and sunshades of various shapes called were used.

Designs of some buildings, especially hospitals, made use of galleries, that is, corridors with rooms on one side and windows on the other. For example, the Rio de Janeiro hospital designed by Oscar Niemeyer is a narrow multi-story building on pilotis on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. The internal corridor and service rooms were shifted to the west, and all the wards face the east, with a view of the ocean. The western facade is enclosed by a vertical sun-shade panel.

Hospital Sul América (1959), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Architects: Oscar Niemeyer and Hélio Uchôa. Photo: Ministério da Saúde / Flickr

Samarkand Hotel (1972–1979), Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Water

Spaces near public buildings, especially near palaces of culture (community centers), sports venues, and department stores, usually contained canals, fountains, water curtains, or pools. Fountains cooled the surroundings, and those that were part of cooling systems even helped avoid overheating in buildings. Such fountains work similarly to cooling towers, which cool equipment at power plants. In such systems, water acts as a coolant stream that removes heat from the building: when it reaches the fountains, they cool it using air currents. In Ukraine, such structures were built near the “Yunist” Palace of Youth in Donetsk; the “Krym” department store, the city council building, and in the Konstantin Trenyov park in Simferopol; the cooling fountains near the central department store in Dnipro and the “Korabel” Palace of Culture in Kerch were demolished.

“Khimik” Palace of Culture (1970), Kamyanske, Dnipropetrovsk region. Architects: M. Bubnov, V. Davydenko, I. Bilinkin and others. Photo: Veselov

Cooling fountains near the central department store in Dnipro. Photo: from the album on beautification by Serhii Podolinnyi / Oleksandr Volok / Flickr

Plants

Trees near a building cool the air by 1.5–2.5 °C. They should be planted near the end walls to the east — southeast and the west — southwest. In the morning and evening, they will cast long shadows. Noon will be the only time when they will be hardly efficient against the sun at its zenith. Trees are also good for controlling wind direction and flow: plant them parallel to the usual wind direction to increase wind speed and perpendicularly or checkerwise to slow it down.

Climbing plants on facades are another way to cool walls, especially if they are placed on lattice structures: this way, air circulates freely between them and the surface of the building. Combined with trees around the building, they can reduce the temperature of the walls by 9–10 °C.

A similar initiative is being put in place in Kyiv: Kyiv City Administration’s department of ecology and natural resources has proposed to plant grapevines on houses and offices. Although it was not long ago that such vegetation was destroyed, as it was with the buildings of Ukravtodor and Kvity Ukrainy.

Musée du quai Branly in Paris. Photo: Chad and Steph / Flickr

Walls and cladding

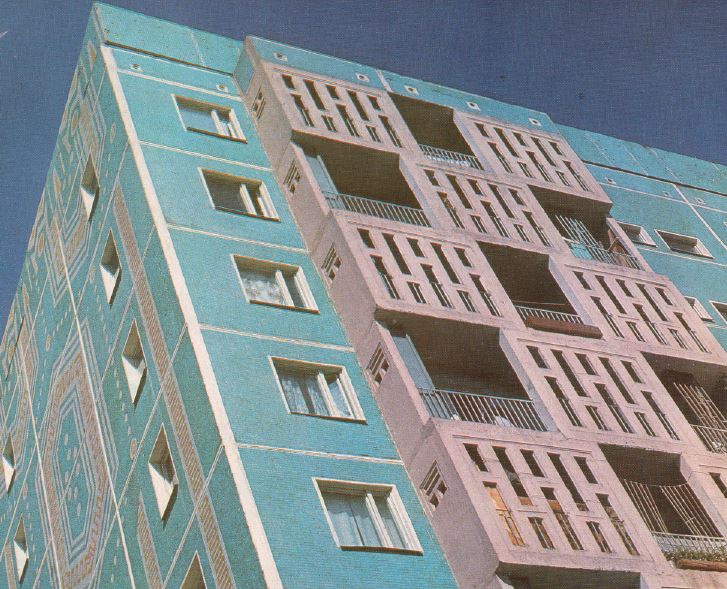

Buildings can also be cooled with stone, ceramic, or glass (tiles and glazed tiles or mosaics) used as cladding or on the floors, especially if the materials are light-colored.

A recent trend is to design black-colored buildings, but light colors are the ones that actually help avoid overheating. The temperature difference between a black roof and a white one can reach 30 °C on a hot day.

Curved, uneven, and wavy surfaces, raised ornaments and reliefs, protrusions and recesses, vaults and domes — they are not just decorations but also thermal regulators. Irregularities increase the surface area, which makes heat dissipate and subside faster. This will work even if you make very small indentations or cut lines and shapes into the walls.

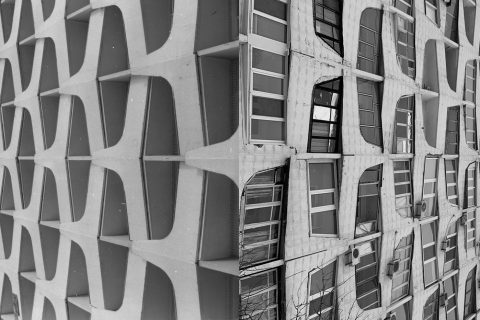

Irrigation Institute (the 1970s), Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Thermal insulation sheets on the wall can be given a certain texture, and outer surfaces can be made with protrusions and recesses. Architects Paul Lester Wiener and Joseph Louis Sert developed a “breathing wall,” which is sort of a screen with holes. Placed on the building front, such a screen provides for air circulation and at the same time blocks sun rays. “Breathing walls” are made of precast reinforced concrete, concrete, ceramics, aluminum, bamboo, and so on. In the late 60s, such walls used to be made of precast elements that would be assembled into ornaments. They not just performed purely “climatic” functions but also accentuated facades.

Such a wall was used for the smoking area in Zhytomyr Hotel

The method used for loggias in a residential house in Tashkent

Brises-soleil

Many elements in modernist architecture are designed to prevent excessive insolation and at the same time decorate the buildings.

The simplest means of sun protection is an overhanging edge of a roof called the eaves. In low buildings, such projections are measured to be half the height of the wall that they protect. But the eaves will not work in tall buildings or western or eastern facades, which take in too much low sunlight in the evening and morning hours.

Another approach is to place loggias in recesses so that their walls act as brises-soleil, creating shade and protecting rooms from direct sun rays. This is a popular technique used for hotels.

Pavilion 13, “Coal Industry,” with the wide eaves, VDNH Expo Center, Kyiv. Photo: Oleksandr Burlaka

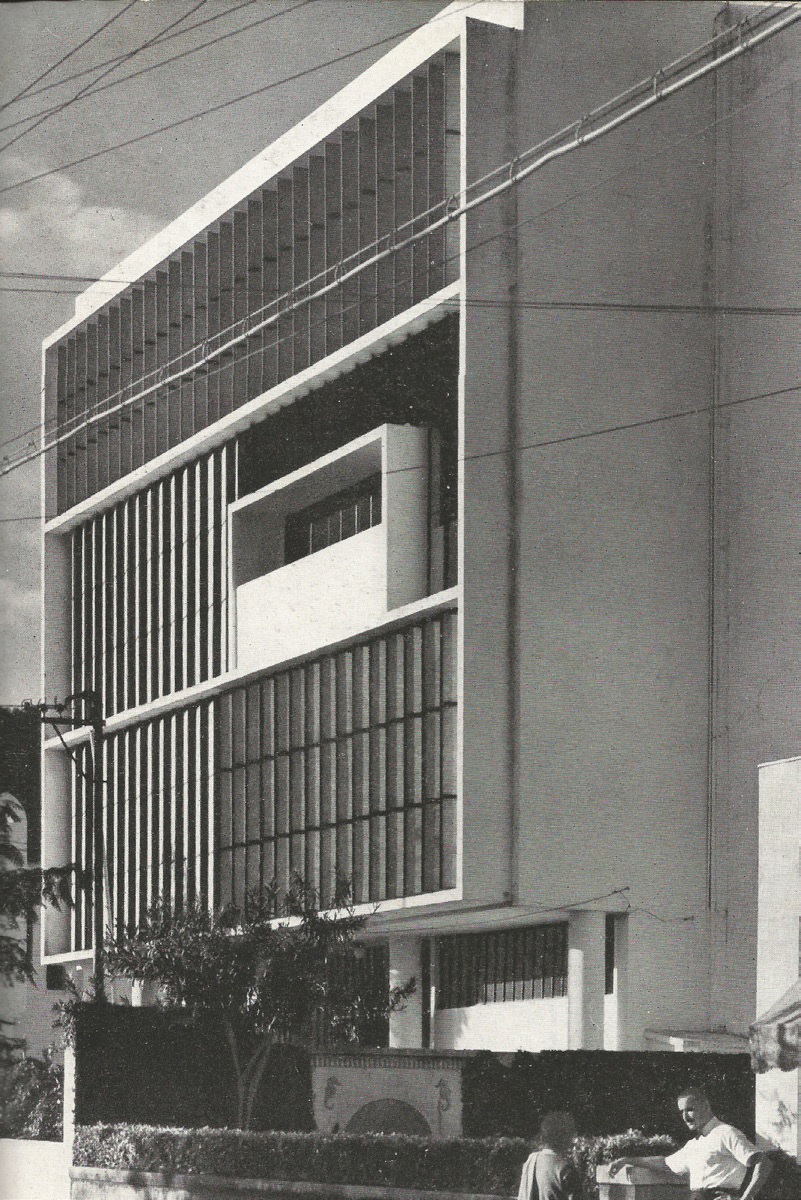

One of the most popular means of such protection was invented by Le Corbusier. He redesigned the already well-known blinds, about which the West learned from Persia, and made special stationary diffusers. They are widely used in Brazilian architecture, where they were called “quebra sóis,” from the Portuguese phrase that means “sun breaker.” A quebra sol is a row of narrow plates placed in front of the facade to create a shade. A quebra sol, or a brise-soleil, or a sun breaker, differs from blinds in that it allows for air passage between itself and the facade because it is placed at a certain distance from the wall. Such designs were used by Oscar Niemeyer, among others.

Daycare in Rio de Janeiro. Architect: Oscar Niemeyer

This principle was implemented by architects who designed the buildings of the Faculty of Physics of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (architects V. Ladny, M. Budilovskyi, V. Kolomiets, engineer V. Drizo) and the main building of the National University of Shipbuilding in Mykolaiv (architects N. Ustinovych, D. Ulyanitskyi, V. Yegorov, H. Kozharskyi, engineer O. Chernyshov)

Brises-soleil can be horizontal, vertical, or cellular (a combination of the two). The choice depends on the orientation of the building. The walls (or ribs) of brises-soleil can be concrete, glass, wooden, ceramic, or aluminum. Such walls can be placed at different angles to the building’s facade.

Another type of sunlight diffuser is sun-shade panels. While also placed at a distance from windows and walls, they differed from Le Corbusier’s blinds in that they were not narrow strips but openwork structures that could also serve as building decorations.

Brises-soleil can emphasize horizontal and vertical rhythms, create a diverse play of light and shadow, and contrast with the smooth surface of walls.

In the Colombian city of Medellín, the headquarters of Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano is under construction. The building will make use of a precast facade system, sun-shade panels, and other means that will make artificial air conditioning unnecessary. And the project of a new Buddhist temple in San Francisco, which is designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, offers facade protection with metal sun-shade panels and vertical brises-soleil.

Brises-soleil on the building of the Ministry of Social Policy (former Ministry of Light Industry of the Ukrainian SSR) in Kyiv. They have been removed. Photo: Mykola Kozlovskyi

Use of the method in Uzbekistan Hotel (1974), Tashkent. Architects: I. Merport, L. Yershova, V. Roshchupkin

Aluminum brise-soleil on the facade of the “Dytiachyi Svit” department store (1974–1987) in Kyiv. Architects: Volodymyr Zalutskyi, Yurii Borodkin

Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano Headquarters, Medellín, Colombia

Interiors

Hard, dense materials that do not conduct heat are used to cover internal surfaces to cool the room. They include polished concrete slabs, terrazzo, ceramic tiles, solid bricks, granite, marble, and the like. In our temperate climate, a “cold” floor of marble, terrazzo, mosaic, ceramic, concrete, or cement-sand tiles will be enough.

6:19 tattoo studio in Kyiv. Architects: Balbek Bureau. Photo: Evgeny Avramenko, Nata Kurylenko

Roofs

One can arrange shallow pools on the roofs of buildings or cover them with a layer of soil and plant gardens. This way, they will not heat up too much.

Moreover, a double roof of concrete, reinforced concrete, and other new materials is also considered effective. Back in 1939, Emery Roth made a country villa in Giza in which the upper layer of the roof acted as a protective umbrella, absorbing heat and not conducting it further to the main roof. The air between these layers could circulate freely, taking away excess heat.

US Embassy in Baghdad. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Cover photo: Druzhba Sanatorium (1983–1985), Yalta, Crimea. Architects: Vasylevskyi, Stefanchuk, Divnov, Kesler. Photo: Depositphotos

If not specified otherwise, the photos are from the private archive of Child of Socialism

New and best