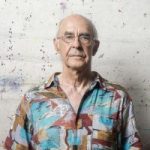

“Distant Explosions. Coffee. A Visit to the Studio”: The Diary of Tiberiy Silvashi

Ukrainian abstractionist. Member of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine and of the National Ukrainian Academy of Arts. In 2022, was awarded the Shevchenko National Prize for his installation “Kryla” . (“Wings”). Has works in public and private collections in Ukraine, Europe, and the US. Lives and works in Kyiv. .

March 6

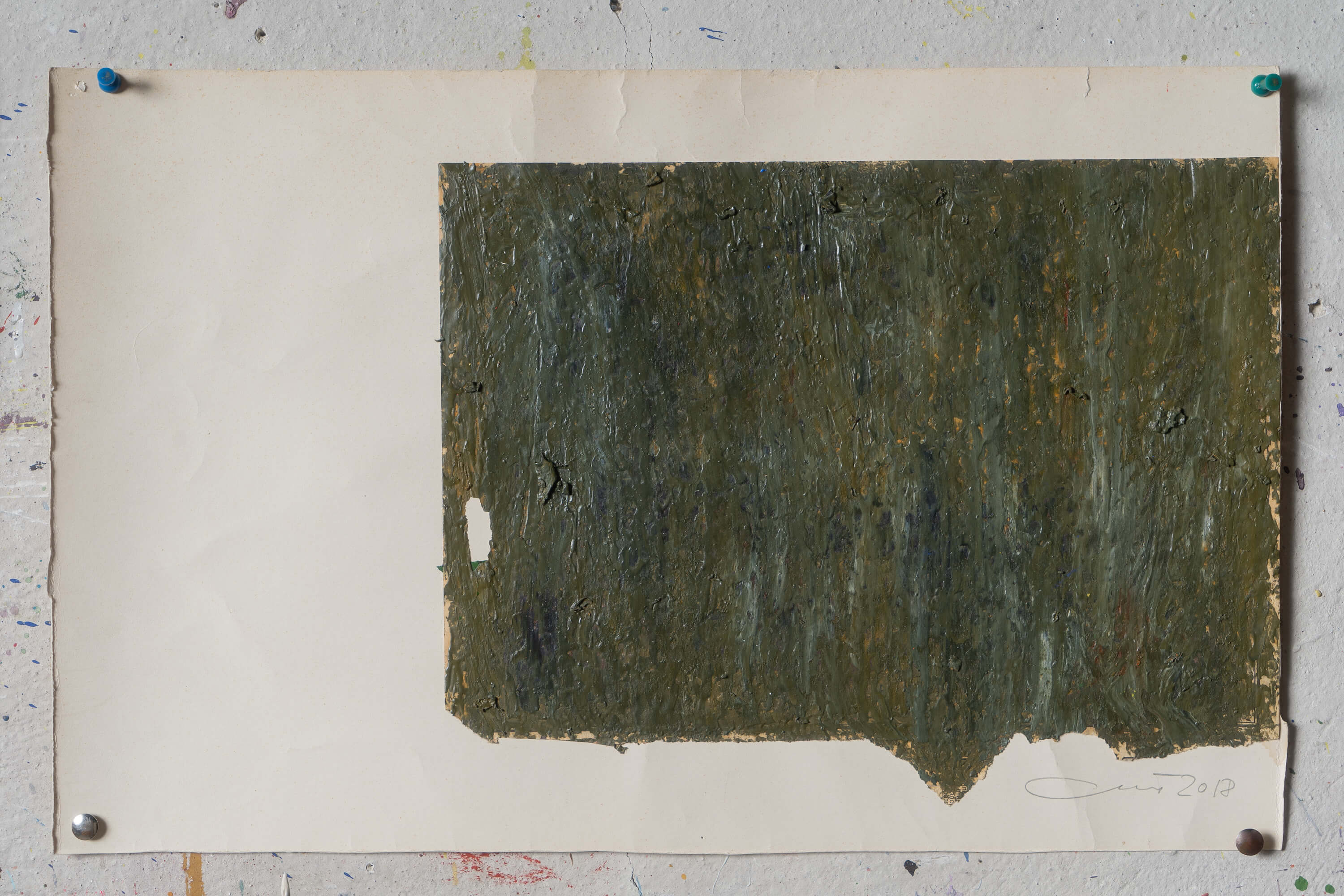

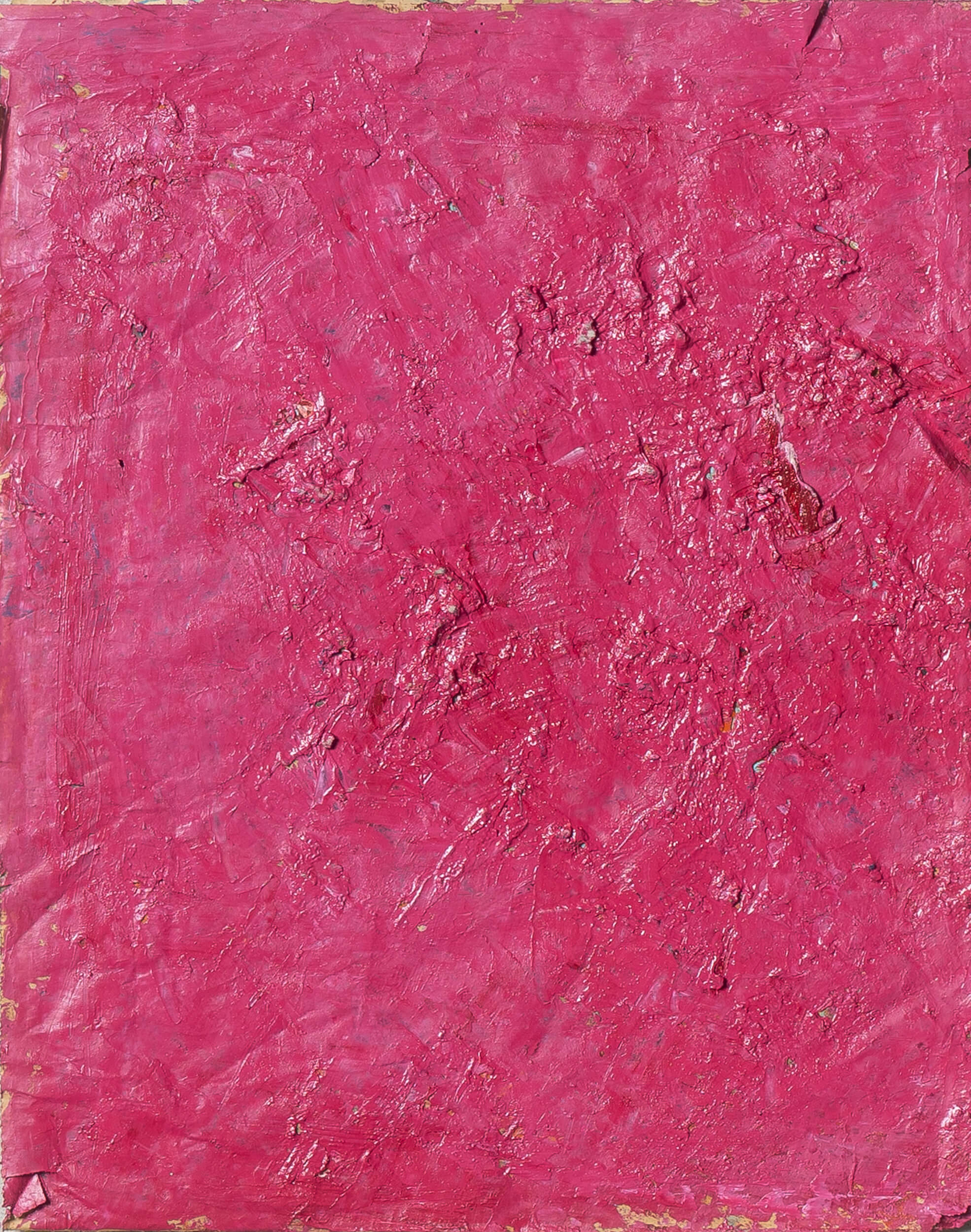

Just like sentences, paintings must be finished. This formula is contrary to my practice, which is: a work (not a painting) is ready on the first day of its creation and never finished. That is to say, we are dealing with the process, not the product. It is a certain ritual that is a result of our choice. A result of how far we can think and how broad a picture we can see. When I started this morning series ten days ago, I promised myself I’d do it for ten days. Of course, I could do it for thirteen, or fifty-eight, or a hundred days. I decided I’d do it for ten. I will go on with it, of course, but it won’t necessarily be regular.

There is an image (a picture), and then there are words. Both words and images have the seen and the unseen in them. The unseen is not necessarily hidden but rather connected with invisible links. There is the word “war,” and it’s unambiguous in its harshness. There is the word “victory,” and it’s present even though it is not written. And between them, there is the word “freedom.” But this word is the most important one because freedom is the choice of a free human being. Someone who is free can make choices and has the opportunity to do so. And they are already the winner! I will go on.

March 10

Year eight, day 15 of the war. A restless morning. A night with a bit of snowfall. Distant explosions. Coffee. A visit to the studio. I’m asked how I’m doing and don’t know how to respond. Apparently, the usual words have lost all their previous meanings. This is a different kind of “normalcy.” We might call it “the new normalcy.” And it is nothing like the normalcy that existed but a month ago.

March 13

Day 18 of the war. Every time I write “day such-and-such of the war,” I catch myself thinking, did I count it right? I feel like it’s really been one long day that cannot be measured in time or split into days and hours.

I feel like it’s really been one long day that cannot be measured in time or split into days and hours.

The morning is gloomy and a bit chilly. We heard several air raid sirens and distant explosions at night, but it’s difficult to tell where they come from when you are in the city. You come to realize that acoustics become the main instrument to identify space and time. Your ears started learning to discern between sounds in the air and on the ground. At some moments, it becomes important whether there is a difference between the sound of an approaching car and the sound coming from the sky. And it’s not only your ears but your entire body feeling the difference between the buzz of a passenger car and the growl of a diesel military vehicle. And your muscles are ready to react in a split second.

While the sense of the surrounding space hasn’t changed much—that is, all the things are where they should be, and your legs just carry you following your usual route—your eyes pinpoint the small details that might have just gone unnoticed in your normal life. Your brain is producing thoughts, and your eyes are recording the cracks in the pavement and the shadows of trees that have nothing in common with the structure of your thoughts. Your body is doing its work. We live.

March 14

Day 19 of the war. The nightly sirens whined a few times. Explosions were heard coming from the left bank. It’s cloudy. A bit chilly. The city is empty. We live.

March 15

Day 20 of the war. Several loud explosions this morning. It’s sunny. We live.

March 16

Day 21 of the war. The night in our district was calm and silent. The morning is sunny. We live.

March 17

We live. It’s day 22 of the Russo-Ukrainian war. The strain of these weeks must be taking its toll now because I couldn’t sleep this night. I was thinking of all the wounds the enemy has inflicted on the people’s bodies, the cities’ and villages’ bodies, the fields, and the stricken trees. The invisible wounds that are holding off your sleep. I was thinking of all the people around the world whose future was distorted by the madness that is this war. I was thinking about cats and dogs. About cranes that will come back this spring and will not find their nests.

My thoughts and thanks go to the people all over the world who are helping my country in these dark times. To our friends, who are doing their best to help artists tough it out. Our artist friends all around the world are raising funds to help

March 18

The world is divided into “before” and “after.” The reality is divided into the experience of a body interacting with space and the acoustic reality bordering on a dream. Between them is the invisible reality of information channeling all three into the shared homogenous zone of one’s psyche. My good friend, film critic Alex Tiutkin, suggested a wonderful edit for my post, and I am thankful to him: “The war has made time homogenous, and calendars, almost redundant.” This is a new reality, perhaps the reality of the “new type” of “war” marking the “end,” as it were, of “the era of the world picture.” Changing a “picture” to a “vignette” doesn’t change the reality of the pain, the tears, the losses, and the sorrows. But it does make one reconsider their ways of understanding the reality that this “vignette” shows. It’s day 23 of the war. It’s sunny. The sky is clear. It’s cold outside. We live.

I was thinking of all the people around the world whose future was distorted by the madness that is this war. I was thinking about cats and dogs. About cranes that will come back this spring and will not find their nests.

Kyiv Non Objective is an art group founded in 2017 by Ukrainian artists Tiberiy Silvashi, Badri Gubinauri, Olena Dombrovska, and Serhii Popov

a group of curators meeting on the 22nd day of every month in the Mikhail Bulgakov Museum

March 27

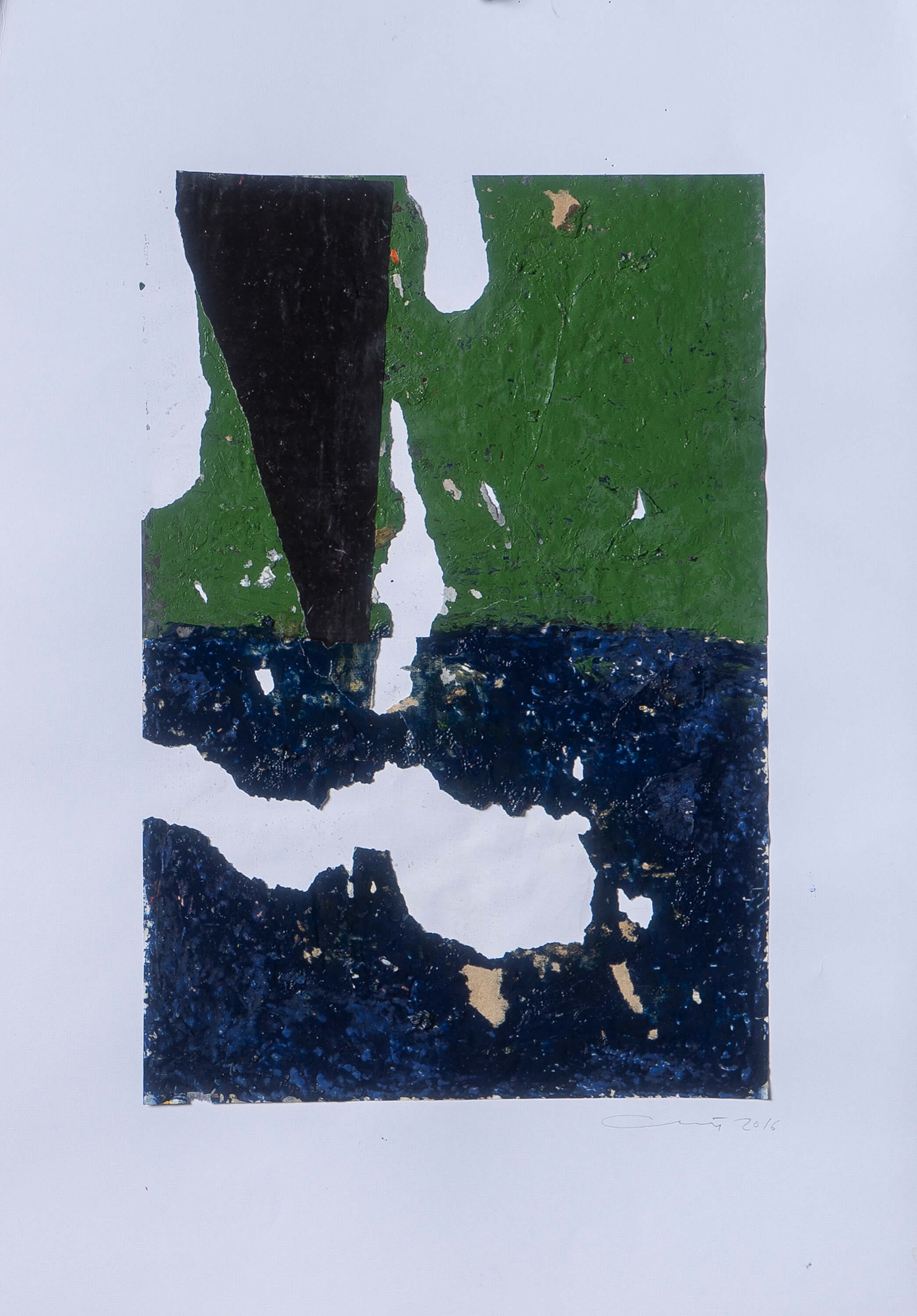

Day 32 of the war. The second month. The second one! We live. The night was relatively silent. The morning is sunny. I go to my studio two or three times a week. Even if I can’t bring myself to do anything, this is my chance to hold the paint tubes in my hands and touch the white canvas.

Somewhere in the first pages of my diary, I noticed and described a certain change that took place in the relations between the outer world and the response to these changes that my consciousness started to record. Time went on, and I came to realize that we are the witnesses of changes, and our bodies, from the tips of our fingers to the way our brains work, are the recorders.

The feeling of space and time changed. Space became acoustic, and the first change was the division of sounds into terrestrial and “celestial” sounds. In your sleep, you can tell between the noise that a passenger car makes and that of a diesel military vehicle. You sharply feel how the space is filled with the rumble of an approaching car, how an aircraft sounds, and how a missile rustles. And then your body learned to respond. Automatically. It learned the difference between “far” and “close.” It knows how much time you have to do this or that. It’s as if your body could “hear” in your sleep. Time split into day and night, and to tell between “yesterday” and “today,” you needed certain markers. Perhaps in words, or in gestures. Or in actions. In their regularity. It gave you just a bit of reassurance that the reality is still there. Photos turned into documentary evidence that it actually happened to you in a particular place. The calendar became essentially the only witness of the change of the dates it showed. Well, there was also television reminding us of the change of time, backing it with military chronicles.

This month of the war is changing something radically. It is changing the way the world is perceived. It is the time when the links between things that seem so far apart become apparent. Many people are saying the world is not going to be the same after the war. It is accurate. But it seems to me that I knew it from some other sources. It seems to me that this war marks the end of an era, the age, as Heidegger put it, of the world picture. It might be more prominent in art. Perhaps it’s the word “picture” that’s important here. Perhaps, as an instrument that is more likely to resonate in response to signals from within, art produced the first examples of these changes. Perhaps Malevich and Duchamp were the first to notice it and “finished” the age of the picture in their own radical ways.

But it never ceased. It went on to construct new relations between the main characters of this drama. The drama that was developing in the dimension of ideas, in between the understanding of new interrelations of a human/subject with the reality/object, between time and space. The World Picture is the golden age of empires and the beginning of their decay. It is the age when nations and countries began. Naturally, it was bound to lead to disagreements and conflicts between them. In his recent essay, Volodymyr Yeshkilev writes that war always works with time, and empires work with space. By working with space, an empire lives with an illusion of controlling time. But to do that, the empire needs to expand into space, which would drive this illusion and gives sense to its existence. This illusion will not disappear by itself. One can only dismantle it.

By working with space, an empire lives with an illusion of controlling time. This illusion will not disappear by itself. One can only dismantle it.

But there is still culture. It shapes the worldview by creating and reflecting ethical and esthetical norms. It lives longer. A geopolitical construct may disappear, but the ideas that drove it and gave sense to its existence prevail. They were an important part of what held the empire together; they were a part of historical memory and a warranty of the future. It may be a quite comprehensive explanation of our thoughts on how this war is being waged and on the fate of culture in general and the role of Russian culture in particular. What did every empire bring to the lives of its subjects? What was organic for producing certain norms of life on this or that territory? What was borrowed and imposed despite resistance? How did this or that religion influence it? Or science? How did certain forms of coexistence deteriorate? Perhaps this war marks the end of the era which is long echoed in culture and art. An autonomous subject becomes dependent on the deterioration of the visual language. A subject of the geopolitical machine called empire becomes its slave, identifying themselves through the monstrous machine.

The picture developed as a space of illusion. Deteriorating, the language of the picture turned the illusion into its imitation and the observer/subject, into a self-expressive narcissist. Doesn’t the same happen to the person who becomes the leader of an empire? Perhaps we need to acknowledge the fact that the age of the picture is a diagnosis. And we have hard work ahead. When relativist postmodernism ends, we will need to build a fragmented world on a different foundation.

I am not sure that the World Picture will help us do it. The “scientific picture,” the “technology,” as defined by Heidegger, becomes servants to interference from the position of power. It’s the same with the language of culture, which the authorities turn into a lever and a cover for their maneuvers. The world is not going to be the same after the war. And if it is, this nightmare is going to happen again and again. We need to define the basis of humanity. And develop a different picture. It is the empire’s last attempt. Is it?

The world is not going to be the same after the war. And if it is, this nightmare is going to happen again and again.

May 2

It’s 20 degrees Celsius in Kyiv. I opened the window in my studio for the first time this year. I knew the day would come when I would have to turn the page of my diary. I wish this were the last page, but I will not forbid myself to open it again… now, it’s time these short notes and photos started living their own life: I was asked for permission to use them in art projects and exhibitions.

It’s calm in Kyiv. There are more cars now. People are walking on the streets. We live. I am grateful to everyone who is supporting Ukraine in these dark times. I am grateful to everyone who shared their morning coffee with me. I am certain that we will go on doing it every morning, sitting at the same table in our minds. We are together, and I’ll be thinking about each and every one of you. Thank you for being there for me. And now, I’m going to finish my coffee and go to my studio.

Photo: Valerii Veduta exclusively for Bird in Flight

New and best