“I Couldn’t Imagine a Happy Ending”: A War Diary

Photography has always been Roman’s way to document reality. He started taking photos after meeting Kyiv photographer Yura Kolomiyets. Roma spent the first two weeks of the war in a small house in the Kyiv region, near Gostomel, Irpin’, and Bucha. By taking photos of his surroundings, he kept his war diary. Bird in Flight publishes Roma’s works alongside his story of living through war.

Born in Nizhyn, lives in Kyiv. Works as an editor in the Ukrainian IT holding, enjoys photography.

— When the war started, I wasn’t at home. That evening, on February 23, I decided to stay at my brother’s place and go to the gym the next morning. I only had a Brazilian jiu jitsu kimono with me.

I remember waking up to the sounds of loud blasts. I checked my phone and saw a lot of people online. Chats were filled with similar messages: “Have you heard it?”. There was a video about a so-called “special operation” and I realized that the war had started.

We spent the first night at home — four people crammed together in a small apartment downtown. We slept between the bathroom and corridor. I had a lucky spot right by the toilet. The second morning we woke up to the same sound of explosions. We watched a video from Kharkivskii district, which was hit by a shell. We got a call from a friend of ours, who was in the Ukrainian army. He told us to go look for a quieter and safer place. After that we headed to a village in the Kyiv region, where my girlfriend’s parents lived. I asked the guys to stop by my place and grabbed a backpack that I had packed for two weeks in advance. There I had a sleeping bag, some cash, and most importantly — my camera. Two minutes after we were fleeing Kyiv. It took us three hours to cover 35 kilometers. We were lucky, though. We moved slowly, yet we moved. We could see military equipment around, air raid sirens went off almost all the time. It felt surreal, as if we were a part of a war chronicle.

I grabbed a backpack that I had packed for two weeks in advance. There I had a sleeping bag, some cash, and most importantly — my camera.

At first, we thought that leaving Kyiv was a good idea. The sun was shining, we were sitting in the countryside, petting cats, reading news, and thinking what to do next. We felt anxious, but everything around seemed so calm.

It all changed in a day. First, there was a power cut, then the water was cut off. Luckily, there still was gas, and we had a well in the yard. There was a gas boiler in the house, so we were able to stay warm and cook food. But the next day we found out that grocery stores and pharmacies were closed. In a couple of days someone brought food to the local plant. After standing in a three-hour queue, we bought flour, salt, butter, pasta and tomato paste.

We heard explosions all the time — some of them were further, some of them were closer. Later, we understood that they were coming from Gostomel, Irpin’, and Bucha.

We set up a place to sleep in the living room. We taped up windows, moved a couch to the wall, and slept there in between. We brought down chairs, yoga mats and sleeping bags to the basement. The moment we heard explosions, we got dressed, put our shoes on and knew exactly what to take with us to the shelter.

While it was quiet, we tried to distract ourselves with some routine things: chopped wood, played cards, read books, cooked or brought water. Time has slowed down. It seemed that days got longer. We would wake up at 4 or 5 in the morning because of the explosions outside. Afterward it was hard to go back to sleep. Several times a day we switched on an old Nokia phone and tuned in to a local radio station to find out the news. In the last days before our escape that old Nokia became our only connection to the outside world. I also never stopped taking photos. It’s my way to document everything that’s going on. Some kind of a diary. Before the war started, I used to carry my camera with me all the time. I did the same back in our shelter house, when no one knew what would happen tomorrow.

We listened to a local radio station on our old Nokia phone. In the last days before our escape that old Nokia became our only connection to the outside world.

I was really surprised by the calmness of the locals. While we were ready to run and hide the second we heard explosions, they kept standing and chatting, walking the streets like nothing happened. One time, they spotted a military convoy nearby, and the neighbor beamed when he told us the news. They have a tight-knit community. They help each other, share food. When my mobile operator stopped working, our neighbor brought me another SIM-card.

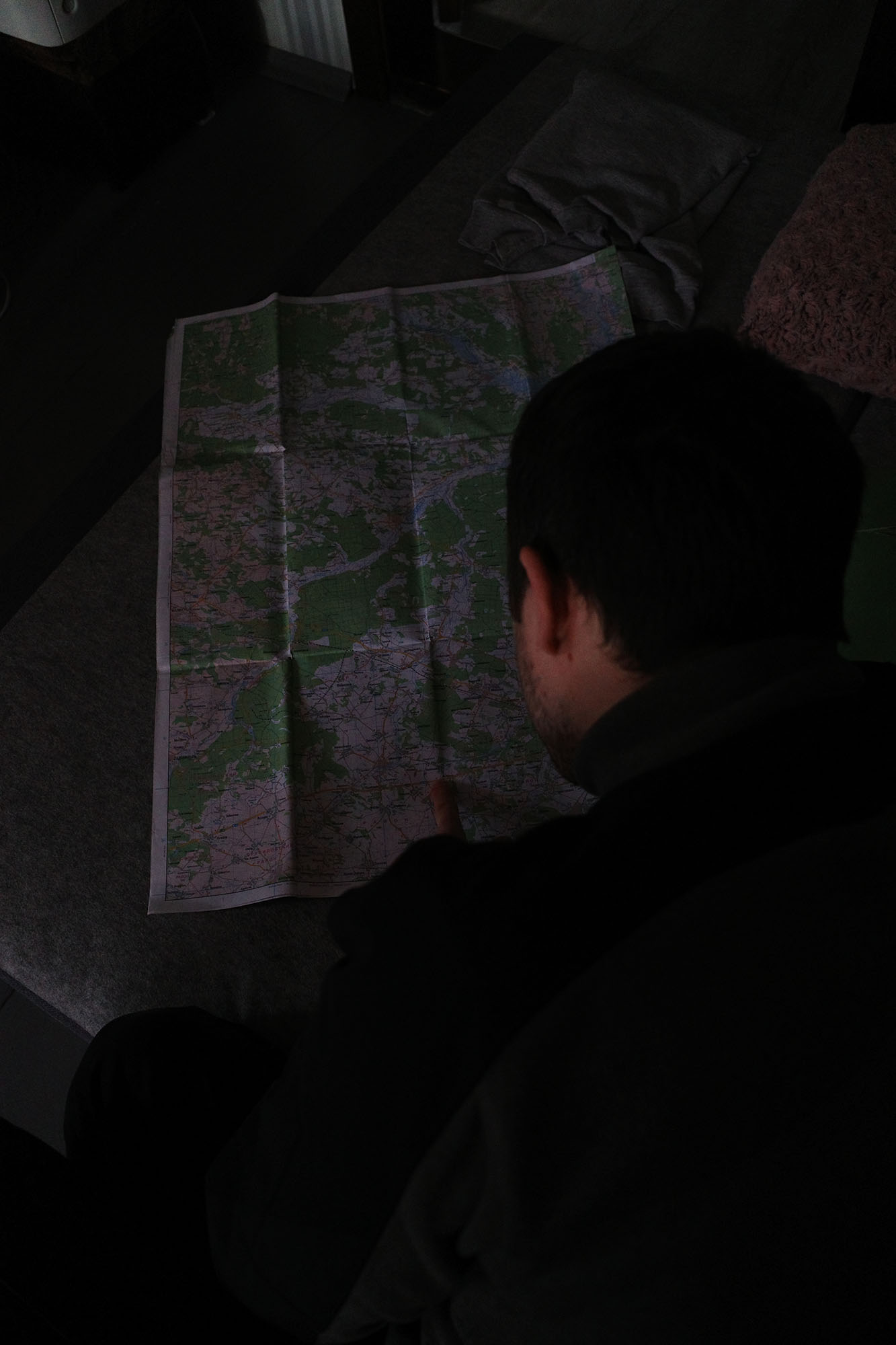

Right before our departure the situation got threatening. We were running out of food, we had almost no Internet connection, and the chances of getting further supplies were non-existent. Russian soldiers had shifted to “self-procuring” mode. In other words, they started robbing our houses. We hid food and devices, I stopped carrying around my camera and put a SIM-card in an old phone in case they took it from me.

We managed to leave on March 10. There was no information about green corridors back then. I thought that trying to leave was a very bad idea. A week before, a father was trying to evacuate his daughters following the same road we were about to drive. Their car was shelled by the Russian soldiers. We were scared, but we heard that a couple of convoys were lucky to leave.

The last days before departure were the toughest. We stopped running to the shelter on every occasion — we just sat and thought about the road ahead. Before going to sleep that night, I kept seeing different scenarios flashing before my eyes. I saw myself being killed at the Russian checkpoint, blowing up on a mine, driving under artillery shelling. I couldn’t imagine a happy ending.

Before going to sleep that night, I kept seeing different scenarios flashing before my eyes. I saw myself being killed at the Russian checkpoint, blowing up on a mine, driving under artillery shelling.

In the morning I had no thoughts and feelings, my head was empty. We got together with other people, put white flags on our cars and set off. There were 30 cars in our convoy.

Every time we stopped, I felt panic rising. We passed the Russian checkpoint. I saw their vehicles with a V letter on them. My brother saw bodies covered in snow. We stopped again a couple of minutes later. I caught a glimpse of the Ukrainian chevrons and felt weak with relief. Our guys had an impressive look around them. They checked our documents and let us go. It was devastating to see the empty road ahead. But it was even harder to look at the photos of destroyed cities of Kharkiv, Mariupol, and Chernihiv.

I’m in Khmelnytskyi now. It’s calm here. Air raid sirens go off a couple of times a day. But overall the city feels like Las Vegas compared to where we spent the last two weeks. Grocery stores and coffee shops are open, public transport is available, life goes on. I’m sure that this tragedy will only make us stronger. And we will win, because the light always defeats darkness.

New and best