Straight from the Streets: Yelyzaveta Bukreyeva`s Portfolio

Photographer. Lives and works in Kyiv. Participant of the ICP Concerned 2020 exhibition in New York, finalist of the Italian Street Photography Festival 2021. Published in Eyeshot Magazine, "The Village Ukraine," Reporters, and Ukraïner.

— I started photographing two years ago, although I dreamt of being a photographer since childhood. I imagined that I would have a camera in my eye and would capture moments by blinking. Several thousand similar images live in my mind. So, it seems, I didn’t have a chance – sooner or later, photography would have claimed its place.

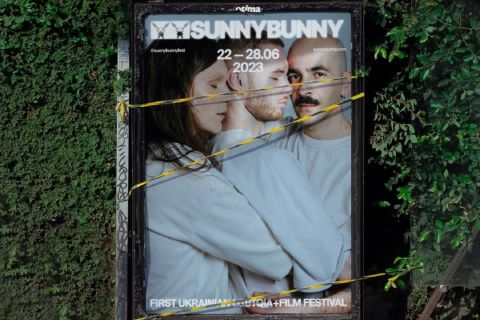

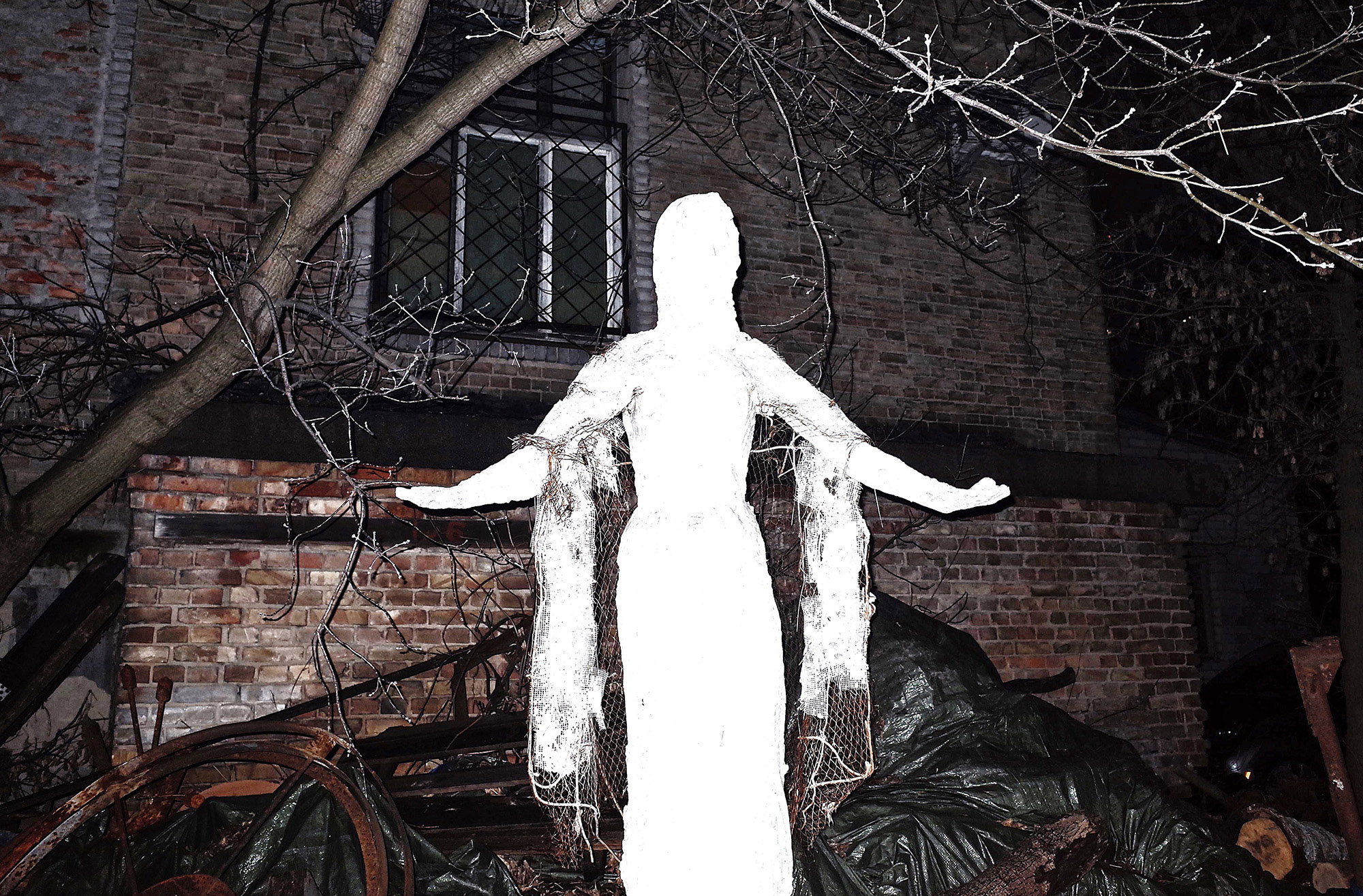

I absolutely love Kyiv; it’s like a patchwork quilt with many different pieces that are somehow connected. I’m interested in everyday life, communities, and local cultural phenomena – both past and present. But I wouldn’t want to give importance to certain events while excluding others, so I capture what characterizes the present time and environment. And it can be anything at all.

I wouldn’t say that I fit into the traditional meaning of a street photographer. Photo anecdotes, muted shadows, anticipating a character or light — those are not my close companions. The documentary aspect is more close to me. Many things go unnoticed by people, even though they see them every day, so sometimes it’s necessary to extract and isolate them from their environment. That’s what, I believe, my photographs are about.

Photo anecdotes, muted shadows, anticipating a character or light — those are not my close companions. The documentary aspect is more close to me.

It is impossible to deliberately anticipate something in such photography; I have no control over it. The only thing I can influence is where I find myself on any given day. Since I work from home, in the morning I choose a street, go there, and take photographs. During the process, I try to think less and trust myself more. In my view, it is important to be open to the moment and, most importantly, not be afraid of making mistakes, because there is no such thing as the perfect shot, nor the unphotographed one. Therefore, between “most likely, it won’t work out” and “capture the moment,” I choose to capture it and then think.

I never hide the camera from people; it’s important to me that it’s visible. Otherwise, I feel uncomfortable and vulnerable. A person should have a choice whether to be in the frame or not. However, I rarely interact with the subjects. When people pose, they try to look a little better. It’s not bad, but then the person becomes the main focus of the photograph, and I want to balance the space and the characters, to equalize their importance in one scene. But if the photograph benefits from having a conversation with the subject, then I will do it.

I haven’t had to delete any shots, but conflicts and threats have occurred. I remember when I first bought my Ricoh GR, I went to the market to take a few test shots, and within five minutes, a drunken man grabbed me from behind and started muttering that I shouldn’t be taking photos. It was an unpleasant experience, but a useful one: now I always keep an eye on what’s happening behind my back.

I don’t have the intention to create provocative or trashy photos, nor do I aim to capture sterile documentary images that are difficult to distinguish from one another. I find myself somewhere in between. I have photographs featuring various individuals commonly referred to as “marginalized.” However, I believe that there is no such thing as a “right” society or a “right” path that everyone should follow. And it’s not just perfection that can be attractive—there are many more sides and qualities to everything.

Not only perfection can be attractive—there are many more facets and qualities to everything.

I feel empathy towards all the characters in my photographs, and fortunately, I haven’t encountered any negative reactions from viewers. If what I see on the streets were turned into a movie, its genre would be tragicomedy, and it would be impossible not to empathize with its characters. I’ve come across various people: older women who are ashamed of their age, children who gave me a tour of the railway “graveyard,” men who shared stories of their first tattoo in exchange for a better jacket, and people who said prayers for my luck. I believe that empathy is essential when capturing moments on the streets.

Currently, I’m working on several projects. One of them focuses on the flea market in Kyiv, exploring the environment of survival and the local community. I’ve been visiting Petrivka every weekend for a year, but this summer the question of whether the vendors will be able to continue working there became particularly urgent. I hope the flea market will endure. Another project is called “Dead Water,” which depicts typical Ukrainian waterfront leisure spots and the seasonal desire for connection with nature. In folklore, dead water heals wounds but cannot bring back life. In reality, bodies of water are often disconnected from the urban environment, with little public information about the number of lakes and rivers in the city. Yet, approximately ten percent of the city’s territory is covered in water that remains “dead” for most of the year, only to be populated by people during the spring and summer months.