The Aftermath of a Civil War: Guatemala after 36 Years of Unrest

Born and raised in Mexico. Has a degree in Cultural Geography from UCLA. Has lived and worked in Guatemala since 2004. Published his works in The Guardian, The New York Times, The Huffington Post, National Geographic, Vice, and many other media outlets.

Feeling out of place in both Americas, I decided to go to the farthest place I could possibly get and took a job as an English teacher in southern Japan, that’s where I really taught myself photography.

A few years later I was hired by the Japanese NGO Peace Boat. They arrange educational sea voyages for average Japanese people: the ship travels around the world for four months visiting different places of the world, they bring onboard different activists, journalists, and artists of all kinds to give lectures, while on land everyone participates in different activities. This how I got involved with human rights. When I decided to return to Latin America with a human rights organization, I tried to go to Mexico but heard about Peace Brigades International (PBI) in Guatemala and got involved.

It was back in 2004, and the war was still fresh in Guatemala since the Peace Accords were signed in 1996. After my year with PBI, I started an online media project about the long-term outcomes of the war, violence, social struggles, and other human rights issues. Within three months of starting the project, Amnesty International, and Oxfam came to me, along with other regional organizations, offering projects, funding, and even publications and an exhibit.

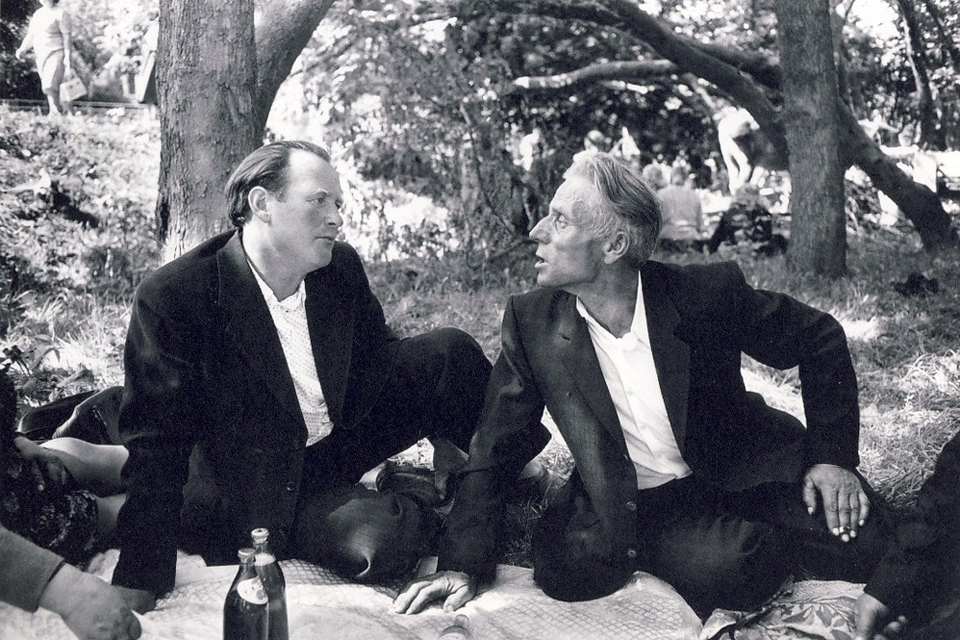

As the years went by, the project grew and I would be sure to put out one photo essay a month. Nevertheless, the quality of my photography wasn’t evolving much, since I never formally studied photography or journalism. In 2009, by pure coincidence, I moved apartments and ended up literally next door to Argentinean photojournalist Rodrigo Abd, then the Associated Press photographer in Guatemala. Rodrigo, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his work in Syria a couple years later, became a mentor. This was definitely a turning point where I saw how the highest level of photojournalism was produced and what was required to succeed in this line of work.

War in Guatemala

In 1954, there was a coup in Guatemala, and it led to decades of military conflicts. Unlike in many other Latin American countries, the war in Guatemala is known for its atrocities and a high victim toll: between 1972 and 1982 alone, 150,000 Guatemalans disappeared. A number of actions taken by the Army of Guatemala were recognized as genocide.

I came to be a freelance photographer with the purpose of carrying out a long-term project of documenting the post-war processes and current social conflicts in Guatemala and the region. Hence, in a way, I think I am a human rights observer. But not in any official way. One of my conclusions is that it is absolutely fundamental to understand the effects of the war in terms of socio-economic issues, as well the flow of migration and roots of the much-publicized gang violence.

From my experience in Guatemala, perhaps the biggest legacy of the war is the normalization of violence in a post-war society. The violence that took place in Guatemala between neighbors and even family members has left deep scars that will take generations to heal.

Guatemala is a very small country, but there are many people in the capital that didn’t even know what was going on in the countryside or in certain sections of the city. Thousands of people were forcibly disappeared by State forces, others forced to join anti-guerrilla community paramilitary groups (known as PACs). There are numerous cases documented where members of the PACs were forced by soldiers to kill alleged guerrillas — even if they were family members.

After the 1996 Peace Agreements were signed, and even shortly before that, war survivors, particularly those displaced internally or who took refuge in Mexico, went back to their places of origin or returned from exile. In addition, after the demobilization of the PACs and nearly two-thirds of the Army, you had victims and aggressors living side-by-side again in every town.

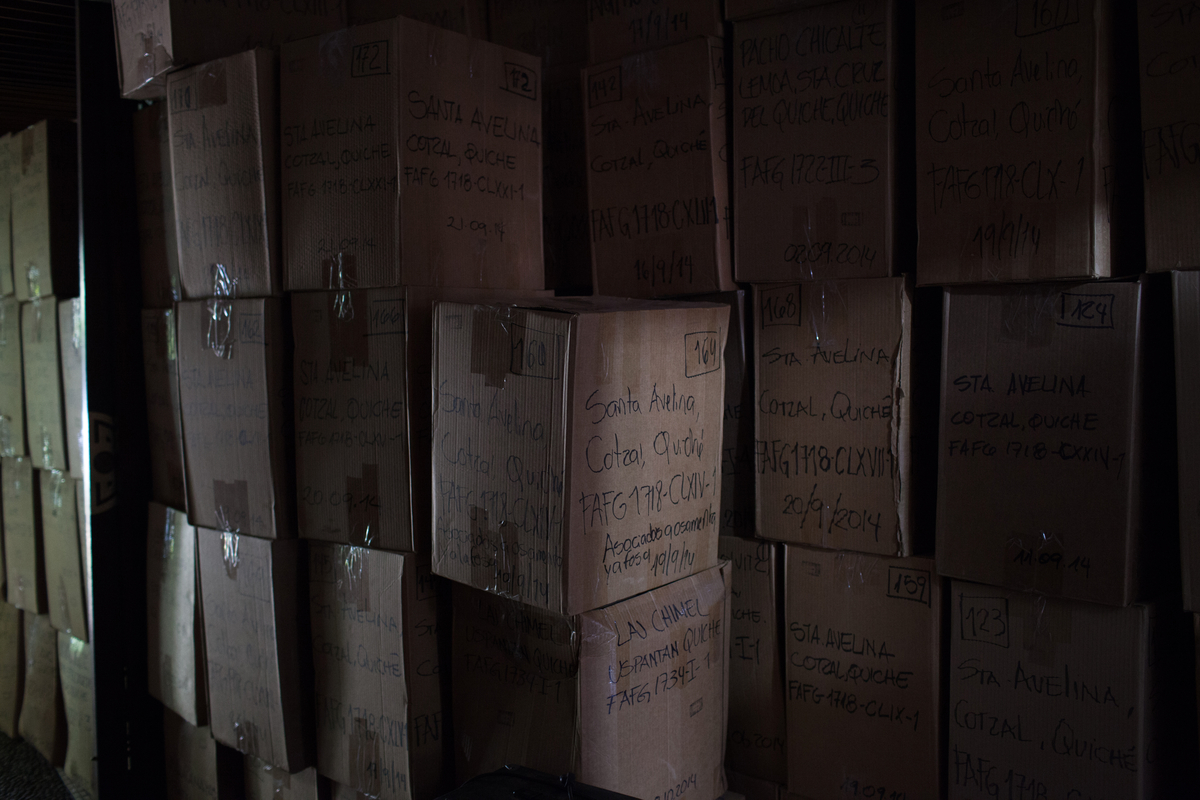

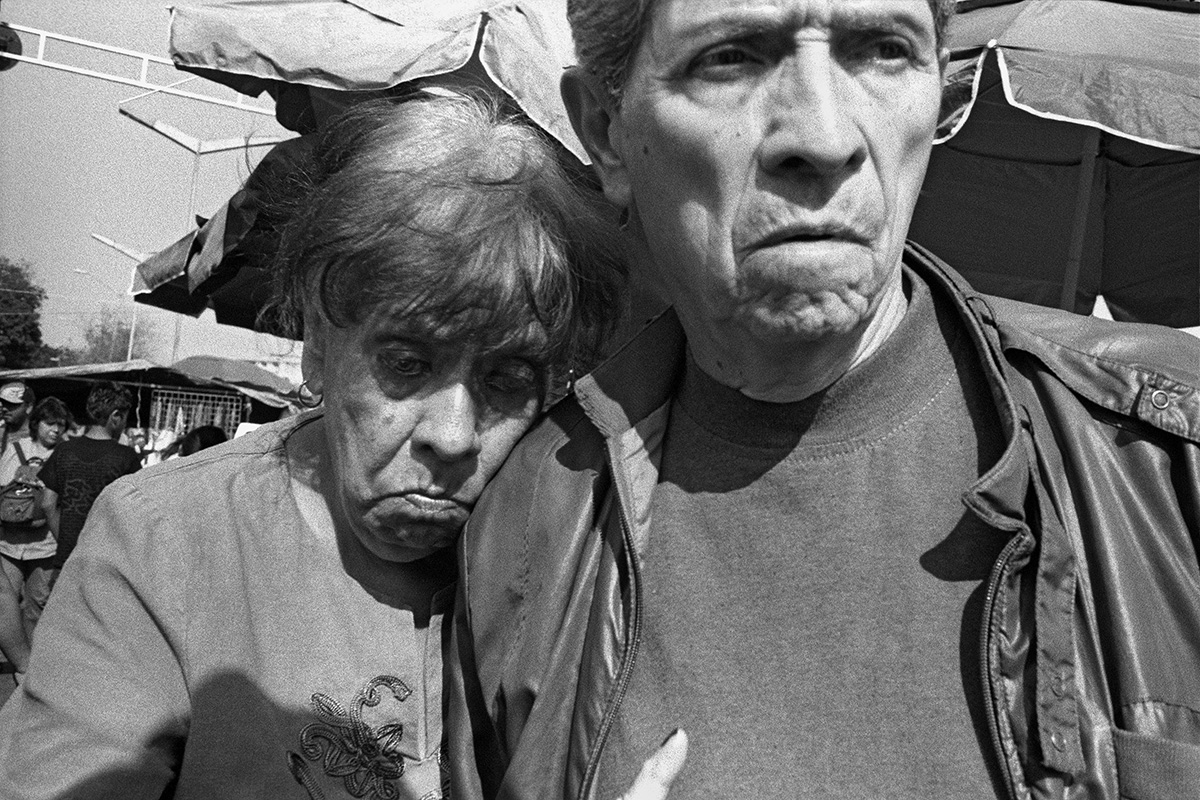

People know where the massacres took place and who did what. I have been told on numerous occasions: “See that drunken man over there… I saw him kill my father with a machete” or “I know he raped and killed my mother and siblings”. How can you go on with life in this situation? And that is a far greater problem than the nationwide rebuilding of the economy or future elections. It is proven war is good business for many. However, many people just want to get their relative’s remains and bury them properly, put a flower on a grave with the name and finally move on. This is one of the strongest emotional and psychological effects that still stirs emotions in Central America. So I have tried to document and share this. The individual person’s experience, the aftermath.

I think the reason there is no end to wars in the world goes beyond violence. It is fueled by power, the nature of greed. And violence simply leads to more violence. How long will it take for Syria, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Central African Republic, to recover? Many people just live in their bubble, they don’t want to know, but we live in a very visual society, so photography can somehow crack that and hopefully place a wake-up call for some. Even if it sounds idealistic, I personally cannot go back living in a bubble.

Every time I attended burials of the remains of victims of war I saw children amazed by what’s going on, shocked. They stare for a long while, they try to understand. And as an outsider, I feel that there a lot of things that are not much spoken about in the communities — be it due to cultural issues, or because death and violence are somewhat normalized. I don’t know.

The way families and communities can bond in Guatemala are one of the ways of dealing with it. Yes, there is alcoholism, domestic and generalized violence, large-scale migration. But even in the harshest and poorest conditions support inside communities can be amazingly comforting.

My main discovery is human resilience. Despite living experiences I can’t even comprehend — to see your closest beings slaughtered and then hide in the mountains for years, or live as slaves, and after this live in poverty or having to face immigration as a way to survive, and yet people continue their struggles, their lives, and still hope for something. It is incredible how people can go on after facing so much injustice and adversity. And this is why I don’t like the idea of coming, taking photos and leaving. People’s stories deserve to be fully told, understanding the context, their history.

I know that my work will probably change nothing for this country. But at least it has changed me. It has been a personal way to understand how life works. The human spirit. Hopefully, I can pass that on to those around me. I believe in the idea that every little drop counts.

New and best