“It’s a Сhance to Do Something Useful on What Might be Your Last Days”: Artists Who Stayed in Kyiv as Volunteers

Photographer, artist, manager at Avangarden, a modern art gallery with a wine bar

“I was panicking on the first day of the war—I didn’t know where to go and what to do. My friends from around the world texted me and offered their help. I could have gone to Germany, Mexico, Brazil, Netherlands, anywhere. I packed my backpack straight off the bat. Took a few things as if I was going to Berlin. We had a chance to flee the city the next day. And there I was, standing with my backpack and weird clothes in it, looking at my son who was saying goodbye to his father, my ex-husband, in a bomb shelter. And I thought to myself: ‘What is going on? Where am I going? What am I going to do there?’ On the one hand, it all seemed reasonable. I have always wanted to live in another country for a while. But on the other hand, it felt wrong. I sat down, turned off my fears for a minute, and understood that I wanted to stay. This is my city, my home. I will protect it and do whatever I can. As soon as I realized that, I felt tranquility and confidence.

The first long-term curfew was hard to live through. There was nothing I could do. I tried blocking hostile websites, but it felt like a drop in a bucket. The moment we were allowed to leave our houses, my friend and I went to the local territorial defense representatives and asked them what they needed. They said they needed food. We handed over all the food we had in Avangarden to the military on the first day of the war, but we still had a kitchen there. To cook more meals, we needed ingredients, but I had no idea where to buy them. I reached out to friends of mine, who run their restaurants. They added me to a group chat with volunteers. With 20 other restaurant businesses, we learned how to exchange products and cooperate together. Now we are able to cook more than 1000 portions per day.

There were only two people from the initial Avangarden team volunteering with me. I don’t even know where the rest came from. At some point, they just appeared at our threshold and started helping out. We now have around 20 people on board. Some of them don’t even realize that they work in a gallery. They just do what they can. I asked them what they used to do before the war. It turned out that we had a ballet dancer as a dishwasher. Our gallery has always united business and arts, and, apparently, it keeps doing that now. We have businessmen from Kherson, dentists, economists, and barbers here.

It turned out that we had a ballet dancer as a dishwasher. Our gallery has always united business and arts, and, apparently, it is still doing the same.

We kept a very low profile in the beginning. It seemed that it was dangerous to speak out and attract saboteurs’ attention. But then we all calmed down and started promoting our work to raise money. Now, we even got in touch with the global kitchen organization—can you even imagine, what am I working on? We receive donations from ordinary people. A friend of mine is a musician from Berlin. He posted a picture of my son, saying that we help feed Ukrainian children. And now we receive donations from musicians from around the world. To live up to that image he created of us, I’ve asked volunteers to direct all children-related requests our way. That’s how we ended up taking care of orphans.

I keep having weird, anxious dreams. But recently I told myself in a dream: ‘If life throws challenges at you, it means that you have enough strength, knowledge, and nerve to handle them. It means you need them.’ And indeed—this month felt like an intensive therapy session. Now I know who I am and what I am going to do when we get our peaceful life back. We needed all these things.

During the past few years, I repeated the following mantra: ‘Art is fulfilling, art is lifesaving, you need no food, no water, just art.’ But this month, I haven’t looked at a single piece of art. Even when walking through my gallery, I haven’t kneeled beside a painting to reflect and contemplate. I haven’t checked one of Pollock’s paintings, which used to calm me down. And it makes me wonder what my after-war mantra is going to be.

During the past few years, I repeated the following mantra: ‘Art is fulfilling, art is lifesaving, you need no food, no water, just art.’ But this month, I haven’t looked at a single piece of art.

My brain is buzzing, it’s like agony. I feel resourceful but I don’t know where I get that energy from. At the same time, I realize that I can die at any moment. I had a dream where my therapist asked me how I am doing. And I answered that I’m okay, just worried about my son, myself, Mariupol, Chernihiv, and all my friends. And my therapist said: ‘Do you understand that it’s not okay?’ And that’s when I realized it, woke up, and cried my eyes out. But then I just carried on with my day.

I don’t think that it’s possible to make art right now. I try to read and to think of future projects. But all I see is cereal, potatoes, cabbage, and spices. My mind is not ready for bigger things. Everything needs to calm down first, to rot inside us — and then projects will grow on the fertile soil.”

Artist, co-founder of the lithographic craft shop Lithography 30

“My husband and I had a chance to leave the country before the war. But we decided not to go unless we can take our family with us. It made our departure almost impossible, so we stayed. Both my mom and dad are bound to military service. It’s not an option for us to sit somewhere abroad and watch our country being bombed. Our friend told us to get in the car and flee about ten hours before it all started. That’s when we knew that war was unavoidable. We went to a grocery store and bought a few Snickers bars. ‘Okay, we’re ready now,’ we thought.

Цhen we knew that war was unavoidable, we went to a grocery store and bought a few Snickers bars. ‘Okay, we’re ready now,’ we thought.

Still, we were shocked and shattered on the first day. We had no energy at all. But the next day I knew I had to get back to work. I decided to go to the nearest grocery store and offer them a hand. That’s how I started volunteering, putting products on the shelves in a local store. Eventually, the store personnel came back to work and they didn’t need my help anymore. But while volunteering there, I noticed that a lot of people used to stand in front of the shelves with baby food, looking perplexed and worried. Those shelves were usually empty. I am a mom and I know how critical that problem could be. And I decided to buy baby food on my own and give it to my neighbors.

My husband and I made a post, saying that we will be handing out baby food in our neighborhood. Soon enough we realized that we wouldn’t have enough money to carry on. This whole time my friends from abroad offered me money, but I kept telling them to donate to the Ukrainian Army. At some point, though, I accepted their offers. We managed to raise enough money to buy not only baby food but also diapers and pills for elderly people.

Now we have 10 volunteers on our team. We see that people with disabilities and those dependent on certain medications are in the toughest situation. I keep thinking that all these people were here before the war, but I didn’t know them. Now their problems and challenges are so clear to me. We have to address these issues when the war is over.

There are many ways to deal with stress. Some people just freeze and do nothing. But I have to stay active. It helps me to live through the days, fills me with the realization that I’m being useful. It was so much harder on the first days of the war when I sat confused and motionless. Now I find pleasure in constant movement. I remember visiting my friends at the beginning of the war, who were sitting at home, pale and exhausted, scrolling through the news feed. After they have joined the volunteers’ group, they look so much more energetic and alive.

I’m glad to know that some people can draw in times like this. I have several reasons not to do it myself. Firstly, I simply can’t force myself to draw. Secondly, it seems to me that I have already drawn my illustrations of war. For several years I used to have very dark and scary paintings. My friends kept asking me, why do I have such a gloomy style? They don’t ask me that anymore. So, to some extent, my artistic job has been done long before the war has started.

When it’s all over, I’m not going to reflect on what has happened. I will talk about the future, about positive things that were born out of this painful turnaround. I’m afraid of the post-war depression. We make so many plans now; we imagine how we will live in a different country, in a different world, where Russia has been punished for its crimes. But we will be lucky to have at least half of our dreams fulfilled. I don’t think that we can expect immediate changes in the first days of peace. That’s why I want to talk about the future, about the results that will come along step by step. And I don’t want to draw bombs that ruin our cities; I don’t want to draw fire that burns everything down.

When it’s all over, I’m not going to reflect on what has happened. I will talk about the future.

At the same time, I have so much respect for those people who reflect, create and show the whole world what is going on. It’s really important now. But I’ve got no energy to do the same. Maybe, I’m acting selfishly. Maybe I’m trying to protect my mental health by doing mundane physical jobs. But if I can help people around me, it’s already good enough for me. Although I remember being at Maidan and feeling united with all the people there, I couldn’t believe that another big tragedy would bring us even closer together. But it did. The cooks at my local grocery store used to make pancakes for me every morning because they knew that I had no time to have breakfast at home. Before the war, I didn’t like their cooking, but now they’ve gotten so much better. I can see how everyone around tries their best to cook better, to help more, and it really boosts my spirits high.”

Artist, co-founder of Atelienormalno (Normal Atelier)—a studio for artists with and without Down syndrome.

“There are several reasons why I’m staying in Kyiv and all of them are important. I always feel a strong connection to the place I’m living in. I’ve been living in Kyiv for four years and it has become my home. Originally, I’m from the Transcarpathian. My parents and my brother live there. But I started telling people that I’m from Kyiv long before the full-scale war. And if I’m from here, where should I go?

I haven’t been protesting at Maidan in February 2014. There were different reasons for that—poor health, lack of courage, and more. I can’t stand not being ‘at Maidan’ for the second time. A lot of my colleagues fled the city and they feel guilty now. I know that I would have felt the same. I think that everyone should decide for themselves, whether to leave or to stay. I’m not going to persuade people into staying, because it’s like taking responsibility for their lives and safety. Since I’m working with non-normotypical people, I know how different we all are. We have individual thresholds of sensitivity. We are affected differently by pain and anxiety—someone freezes, someone fights.

A lot of my colleagues fled the city and they feel guilty now. I know that I would have felt the same.

Another good reason to stay is the fact that I’m working in a studio for artists with and without Down syndrome. My colleagues with Down syndrome helped me to see Kyiv from another angle. They are all staying in the city; they don’t want to leave. That’s why Katya (Kateryna Libkind, artist, co-founed at Atelienormalno) and I decided to stay here too. From time to time, we re-evaluate this decision but don’t change our minds, since nothing threatens our lives right now.

Lately, we’ve been doing a lot: we helped people find useful contacts or places to live. Apart from that, we’ve been helping one of the city’s hospitals. I won’t share the details because the tragic events in Mariupol taught us not to spread information about refugees and vulnerable people’s whereabouts.

At first, I was looking at the works of my colleagues and thought: ‘It’s so cool, they have free time to draw.’ Now I know it’s nonsense. I have free time to draw too, I’m just choosing to do other things. Lately, I’ve been working a lot with words. I’m an art curator, I’m used to reflections. And I’m trying to think and comprehend more. Recently I went to a church and the local priest told me to look at the cross and think about the Passions of Christ and resurrection. After that, I made a couple of crosses myself. Don’t know if that can be called art. In any case, modern art has many faces. Take, for example, Tiberii Silvashi’s Facebook posts—they are both a diary and art.

At first, I was looking at the works of my colleagues and thought: ‘It’s so cool, they have free time to draw.’ Now I know it’s nonsense. I have free time to draw too, I’m just choosing to do other things.

I’m happy that there are artists who can draw and show us their works. We are all different and that’s a great thing. There were artists at Maidan too. What were they doing there? Someone stood at the barricades, someone helped to cook, and someone, like Zhenia Samborskiy, created a sculpture. The nature of art and inspiration differs a lot. Some people need solitude to create, others need instructions from clients. Some people draw inspiration from friendly chats, others—from pain, tortures, or erotic passion. We all have much inner energy now, coming from adrenaline, fear, compassion, and love. And we all transform it into something. For me, helping others is my way to be useful in what might be my last days.”

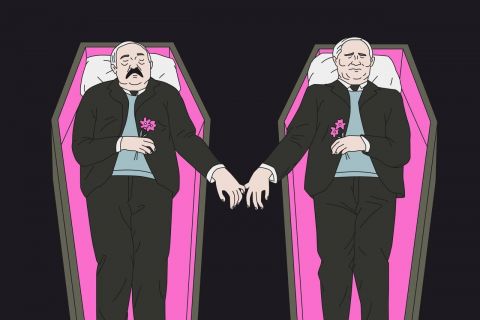

Cover photo: Svitlana Levchenko

New and best