“There Were More Bodies in the Streets Than You Saw in the Photos”: Stories of Bucha Residents

Left the town with her husband and a 4-year-old daughter on the 1 st of April

— My husband and I lived and worked in Bucha. Our house stands near the central part of the town. There are high-rises on one side and the field on the other. I used to lease premises in the neighbouring high-rise for my language school.

We had cell service, internet, running water and such for less than a week after the war began. Then everything was down. We were lucky to have a house with a well in our yard: all that time, we had water. As far as I know, those sheltering in high-rise basements had to drain water from heating radiators. However, we had to go out to get water very early at dawn to avoid being seen by Russian troops — they could see us from the street. Their tanks were parked not far from our house.

We had to go out to get water very early at dawn to avoid being seen by Russian troops. Their tanks were parked not far from our house.

Having a summer kitchen with a stove to cook food also helped us survive. The entrance to the cellar was there, too, so we could hide quickly. So, when a shell hit the ground 10 metres from us, and the shock wave broke windows and doors, it took us barely a second to take shelter there. We thought we would see only ruins around when we got out, but the shell only left a massive crater in our neighbour’s vegetable garden.

My mother-in-law refused to leave Bucha, like many older people who said that nobody wanted them elsewhere anyway. In addition, I was afraid to pass the Russian checkpoint — even though I deleted everything that could raise suspicion from my phone, like my student’s phone numbers. I didn’t want them to find out that I was a teacher. This was why we stayed in the first place, and then it was too late to evacuate. The last relief corridor was on back the 21st, but it lasted for no more than 15 minutes and opened without warning. When my husband made it there, he only saw the buses leaving.

Still, my husband kept returning there to find out something about the evacuation — without cell service, he had to go all the way to the city administration building. Granted, it was risky because he had to cross the street, where the tanks were parked, or the field, where Russians were seen, too. Once, I looked in the window in that direction and saw about 30 helmets moving by.

We heard explosions and small arms fire all the time. The single shots were the scariest. My husband tried to calm me down. It was just a gunfight, he said. But those were single shots as if fired at some concrete target. He talked little about what he saw outdoors, so I realized the gravity of the situation in Bucha only when we set off. I remember the day when he returned and broke into tears. After that, he started telling me how other men and he gathered those bodies. I mean, there were even more of them than now, not the few bodies here and there that we see now in the photos.

We heard explosions and small arms fire all the time. The single shots were the scariest.

At one point, he even met a Russian soldier in the field after the beginning of the curfew. It could have ended badly for him, but the soldier turned out to be a Ukrainian and just let him go. I mean, that guy was a Ukrainian who moved to Russia some time ago.

People could go outdoors only wearing white armbands. The soldiers searched everyone they saw in the streets, checked IDs, and made people undress as if looking for some tattoos. Also, they prohibited the use of any transport. A man who used a moped to bring water to a shelter was shot dead.

In a week or two, I heard a generator working in the neighbours’ yard, and we came over to charge our phones. We even got some cell services, although it took us going to the attic. We contacted our relatives in Lisova Bucha, which is between Bucha and Irpin, and discovered that they had evacuated. They said it was sheer horror in their town because the shells shot from Bucha in the direction of Irpin sometimes hit houses there. Everything was in flames. My relatives reached Romanivka on foot and were evacuated from there.

We saw soldiers go from door to door, enter houses, and destroy everything inside. They came to us, too. I don’t know if they stopped because my older mother-in-law met them at the door, or it depended on who of them entered the houses, but they just went away. From what I saw, they were some kind of Buryat or Yakut men. Perhaps, that shelter in our summer kitchen saved us because it was rather inconspicuous. They weren’t even that interested in houses, preferring to loot the mall instead.

One day, my husband went to find out if there would be an evacuation, and it took him longer to come back than I expected. I lost my nerve and went to look for him. Granted, it was stupid of me. When I saw that the doors of my language centre were open, I decided to take a peek inside. Everything was in disarray as if the Russians had made their base of operations there. From what I saw, someone drank coffee there. However, I can’t wrap my head around one thing. I had a whiteboard there and some pens. Naturally, they wrote “Russia” on it and “Glory to Antiterrorist Operation.” But what struck me were the words “Forgive and understand” written on the wall. The word “Forgive” was misspelt, but it’s not the point. The point is how cynical it looked.

What struck me were the words “Forgive and understand” written on the wall. The word “Forgive” was misspelt, but it’s not the point. The point is how cynical it looked.

It’s a miracle that we escaped the worse and managed to get out. We spent our last week in Bucha in a flat near the town administration, waiting for evacuation. Going back to our house was risky because we barely evaded tanks and soldiers on our way from there. We found a mattress in that flat and slept on it in the bathroom. One night, a shell hit that building. From the impact, it seemed that it hit our very flat, but it was somewhere next door.

There was no official evacuation, but we went as far as the hospital to find out anything about it. I had never been that far from home, so we decided to walk a little further. And there it was, a white car with a red cross driving in our direction. The driver asked why we hadn’t evacuated. Those were the volunteers organizing the evacuation of injured and older people. They seated us in an escort car. The other one’s windscreen had a hole from a shot. We knew that enemy hardware had already left the city. Still, we were scared, as it could very well wait somewhere beyond Vorzel.

While on our way, I noticed a high-rise with a gaping hole. I even asked the emergency team member in the driver’s seat if it meant that the building was shot deliberately. I could understand that a building would burn down by chance if a shell fell near it, but it was evidently done on purpose in that case.

I was worried the most about my daughter. She had just turned four, and we didn’t even realize that day that it was her birthday. We just lost track of time. Now we are safe, but she sometimes asks me about the entranceway doors: why they are damaged and if it was from shelling. And the doors are just old. It was so silent on our first night here that it felt weird falling asleep. Back in Bucha, we went to bed as soon as the sun went down and kept our windows covered so that nobody could see we were there. Usually, there was a pause somewhere around 7 PM or 8 PM, and then they continued the shelling. And now my daughter asks, hearing this silence, “They will not shell us today, will they?”

Internet marketing specialist, musician Stayed in Bucha until the return of Ukrainian troops

— Our family couldn’t leave Bucha. My dad has Parkinson’s and underwent serious surgery in the summer. He didn’t regain enough strength to make it to the evacuation assembly point. My dad and I tried to persuade mum to go, but she refused. They tried to convince me then, but I didn’t want to leave them there.

About the third week of March, volunteers were supposed to arrive by car to get them. We had been waiting for four hours, but nobody came. As it turned out, the Russians didn’t let the volunteers in the city, opening fire on their cars for no reason.

Our house came under shelling on the 19th of March. When we heard explosions, we ran outdoors and took shelter in some kind of engineering structure. Now that I think of it, it was kinda ironic: if a shell hit it, it would have been immediately destroyed.

As a child, I had to flee from a dog once. I felt fear, but then I got a second wind and managed to escape. When the shelling began, I felt fear, too, but there was no second wind at all. I have no words to describe this feeling. The brain signals you to run in one direction, but the body runs elsewhere. I heard explosions for three days after that, even when it was calm outdoors (starts crying — author’s note).

The brain signals you to run in one direction, but the body runs elsewhere.

We moved to the basement when the shelling ceased and lived there for almost two weeks. We had no problems with food. City authorities permitted people to take food from the Novus and ATB supermarkets one day, having agreed on it with the chain management or something. Our neighbours brought shopping carts with necessities, like porridge, water, and toilet paper.

One day, Russian tanks started shooting at the town water service company’s water tower near our place. And they missed once, hitting our block of flats and partially destroying it. We were lucky, though. Our flat was undamaged, and all glass was broken in our neighbours.’ But that’s no big deal — glass can be replaced.

The first Russian soldiers that entered Bucha behaved OK. They didn’t threaten anyone with weapons and said they would not shoot at civilians. When I was away, they came to my parents’ place. However, they talked respectfully, as the military officer saw that dad’s hands were shaking.

Then those soldiers were sent to Kyiv, and those who came after them were veritable brutes. Noticing a mere glance in their direction, they would start shouting, “Stop looking, or I’ll shoot!” After a few days of occupation, I could tell by a soldier’s face whether they would shoot or not. If they turned to you quickly, it meant nothing good.

Soldiers always search for flats overlooking the city. They asked for keys at first but then just started breaking in. If something took their fancy, they seized it. Searching the flats, they took people’s phones and SIM cards. We hid ours in the pad packs and behind the icons — the Russians didn’t touch those.

The Russian troops positioned their artillery in the yards, hiding it behind the high-rise block of flats. And they fired in the direction of Irpin. People still lived in some of those buildings. There was a heavy gun straight in our yard. The sound of it shooting was so terrifying that it took only two shots for our neighbours who remained in the building to leave. They risked their lives, mind you.

One day, I started counting how many shots the gun in our yard took during the day. That day, it was 500 in total, and the other time it was 2,000. It was scary, but then it got even scarier. More Russian soldiers and guns started to arrive, shooting even more often (starts crying — author’s note).

Some people said that the Russians leaving Ukrainian towns razed them with their artillery. So, when the artillery thunder ceased in our yard, it was terrifying for all of us. An hour passed in silence, and then another, and yet another — it was a scary time, and we all were terrified (starts sobbing — author’s note). Later, when someone got cell service, they said that the Russians had crossed the Belarusian border, and we sighed with relief.

When the artillery thunder ceased in our yard, it was terrifying for all of us.

I woke up every day, and I didn’t know if I would live to see the evening. When we could listen to the news on the radio, we were proud of the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ every victory (starts sobbing – author’s note)… Let this sink in: our corruption-ridden country that lacked quality weaponry for years is now pushing back the enemy. The Ukrainian Armed Forces are doing a tremendous job. We couldn’t believe they would finally reach us here. I broke into tears when I saw our soldiers (starts sobbing — author’s note).

Don’t get me wrong, I was calm throughout all of that. Anyway, our people are tough and strike back as one. It’s just now that I let myself cry a little (starts sobbing again — author’s note).

Left Bucha with her parents and grandfather on the 10th of March

— On the 26th of February, I learned that the Russians were entering Bucha. I went to the central part of the town to get groceries. The Territorial Defence Force soldiers didn’t let me through then, saying that an enemy armour column was trying to enter the city. The column was destroyed then.

When I went there the next day, I saw about 20 destroyed Russian vehicles there. Some things were scattered all around. I memorized one surname on a coat — Magomedov. We were warned that some Russians were still hiding in the city, but people didn’t care. About 50 locals gathered there. Some of them were with kids and showed them what the Russians did. I took some of those things as souvenirs: a deodorant, a dry ration, and a backpack. I was happy to know that the Russians were driven out of our land. I was confident that it would always be like that.

I have never heard the air raid sirens in Bucha. I learned about them from Telegram channels and from the noise warplanes made. I don’t know how others knew about them. In the morning of the 4th of March, the first mortar shell hit the street near ours. I took the tourniquet, ran out, and saw a dead old man sitting on a chair. He is still there, waiting to be buried. His wife was hysterical, and we had to promise her to look after their dogs.

The following morning, I read that Russian troops had entered the town. And that very evening, the first mortar shell landed in our yard. The fence was smashed, decking was destroyed, and window glass broke. Our neighbours’ house had no roof anymore. The shelling continued for 12 hours. However, I sighed with relief because I had read somewhere that the artillery doesn’t shell the same place twice.

Electricity, heating, water, and gas were down back in end-February, and we lost the internet on the 4th of March. It was 13 degrees above zero in the house, so we had to sleep together fully clothed and under three blankets. I always felt sleepy. We had enough food, but the stress suppressed hunger. I had the first proper meal only after I left town. Paradoxically, it became psychologically easier when it all ceased. The family pulled itself together because everyone realized there was no time for despair. We remembered family stories and played games to distract ourselves, and mum sometimes prayed. When Bucha was occupied, it became quieter outdoors.

I was scared for the first time on the 7th of March when 30 armed Russians who arrived in APCs entered our relatives’ house. Before that, they killed our relatives’ neighbour. My sister and I arrived 20 minutes after the occupiers left the house. Listening to my relative, I was sick to the point that I wanted to vomit. I knew that I was f*cked if the Russians got to our house. I had clothes with the Armed Forces of Ukraine insignia left from my ex-boyfriend and an Azov Battalion poster hanging on the wall. Having returned home, I started hiding those. I buried some documents near the house, hid the clothes in the laundry, and put the phone in the hole behind the shelf.

I knew that I was f*cked if the Russians got to our house.

We learned about the first relief corridor on the morning of the 9th of March when I got an internet connection by some miracle. Our neighbours started leaving town en mass at the time. We decided to leave Bucha the following day. I resisted till the end: it was my home, and I didn’t understand why I had to leave it. I wasn’t afraid to die — it would probably have been quick. I was scared of being raped by the Russians. I heard about such cases from the people I know.

Finally, my dad said he would tie me up and take me from there by force if he had to. It took us 10 minutes to pack our things. We left behind our pickup (Russians opened fire at big cars like these at once), electronics, and jewellery, taking only our clothes, cat, and dog.

I wasn’t afraid to die — it would probably have been quick. I was scared of being raped by the Russians.

It took us four hours to get from Bucha to Kyiv. We passed four Russian checkpoints on our way but were never stopped or checked. Beforehand, we cut a white sheet and put its pieces on each window. Russians in Bucha looked dirty, their clothes were either too big or too small for them, and checkpoint guards wore stolen Ukrainian uniforms. We passed crushed cars and dead bodies on our way. I tried not to look at them.

I didn’t return to Bucha until the 3rd of April. When we approached our house, I broke into tears. The Ukrainian soldiers entered first to make sure there were no mines or traps inside. We knew that the Russians were at our place. They called dad on the 11th of March (must have found his business cards on the table) and praised our house. I was disgusted to see that they rifled through my underwear, slept on our mattresses, and broke our chandelier for some reason. Clothes were largely untouched — they took only my warm clothes.

It was even harder to go back to Kyiv. Now I don’t know if I will ever return to Bucha. I was eager to see the town liberated, but not at such a cost. Now I don’t know if I will be able to make myself walk the streets in which dead bodies lay. In March, I made every effort to join the Armed Forces of Ukraine to defend my home, but they didn’t let me. Although I still want to join the military, my biggest motivation at the time was to help liberate Bucha.

People in the town said that Buryats and Caucasians were the cruellest. I saw only the former. Positions of the latter were in the part of the town where the most bodies were found. Russian conscripts told locals they didn’t want to be there and fight, but it doesn’t redeem them. I don’t blame the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ command for letting the Russians surround Bucha. Only the Russians are to blame for all these casualties. I hate them.

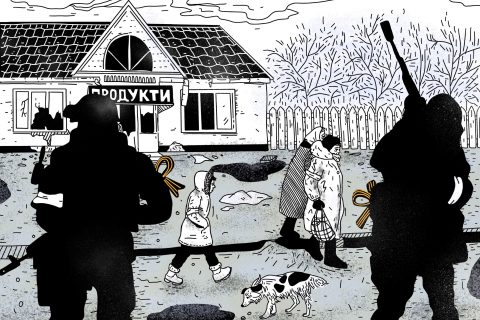

Cover photo: Vadim Ghirda/AP Photo