“After the first kill I threw away my rifle. Felt it was unfair:” An Interview with a Ukrainian Sniper

Sniper S. (upon hero’s request we cannot disclose either his real name or his callsign) joined the ranks of the Ukrainian armed forces in 2014. Having no experience of military service at the time, he enlisted in one of the volunteer fighting units in the Donbass War after taking an active part in the events of the Maidan Revolution. S. fought on the frontline for almost a year before quitting his army job for a more civilian career path in 2015. In a short while, he started experiencing the symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and spent the following seven years fighting the condition. With the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russia in late February 2022, S. returned to the army and to his erstwhile military profession. Evheny Osievsky asked him about the peculiarities of a sniper’s job, professional rituals, as well as the most horrible and the most absurd stories of war.

How does one become a sniper in the Ukrainian army? What was your story?

At first I ended up on the frontline as a rifleman. The superiors observed us closely at the shooting range; took note of guys with good aim. I had an additional advantage: liked drawing since high school, so was used to gauging distances and proportions. The command noticed, gave me some cans to shoot at the training camp in Sloviansk. Then I was handed an SVD and told to pick a partner. A sniper never works alone.

Really? What does a partner do?

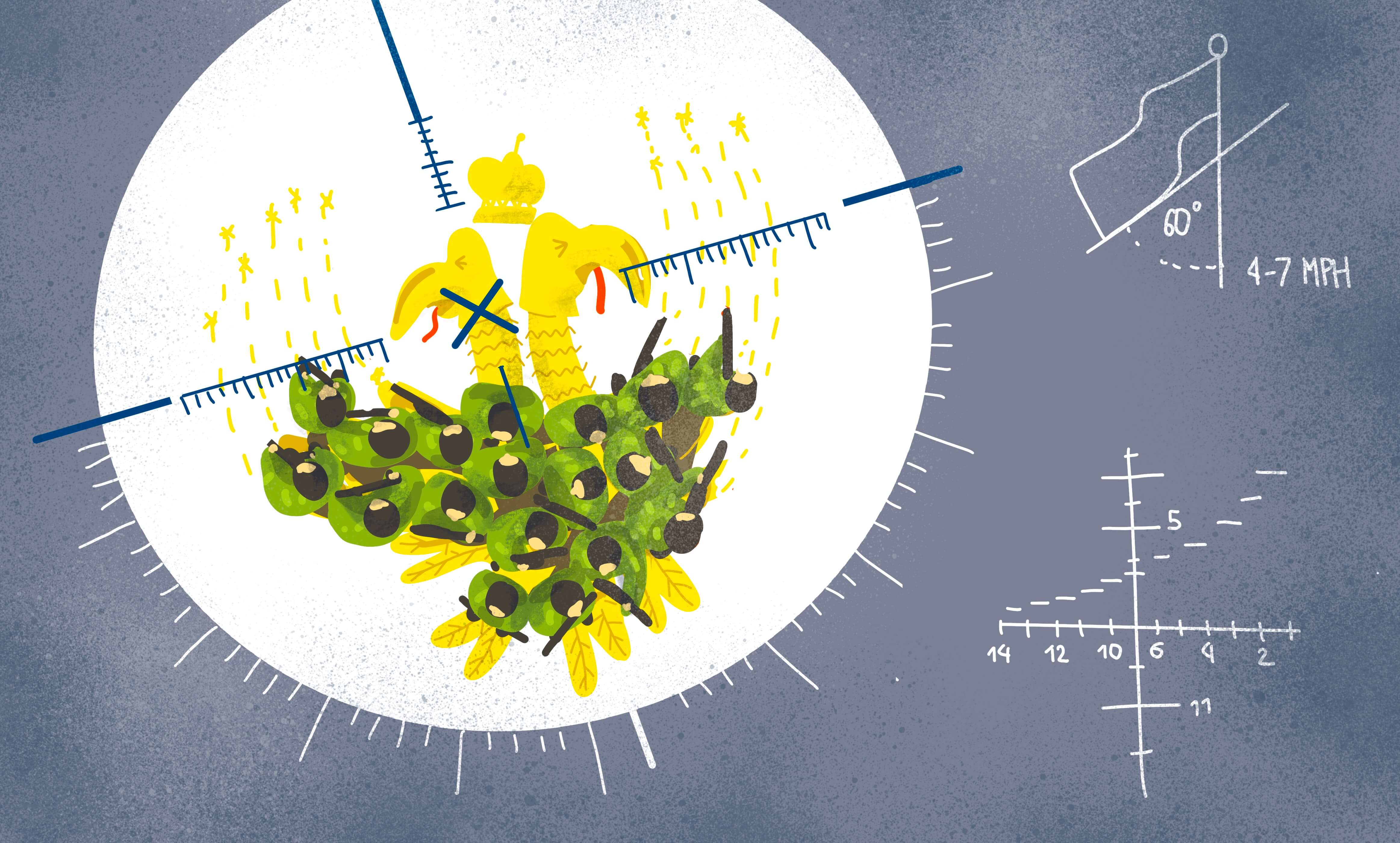

Well, you can work alone if need be, but it rarely, if ever, happens. Your partner is a spotter. He sits nearby with a range-finder, cues you on the distance to the target, wind direction, landscape features, and reads the terrain at 360 degrees. His responsibility is to ensure you’d not get encircled or shelled, because you see only through the scope. Though, eventually, I learned to look with both eyes.

There are two images of what a sniper’s job is actually like. In the first one he is more of a mathematician – he calculates and models, makes notes in a notepad. In the second he works instinctively, makes instant on the spot decisions not unlike a jazz improviser. Which one is accurate?

It depends. In the autonomous mode, if a sniper and his partner work away from the rest of the regiment for several days, you have enough time to make preparations: you sketch the terrain, build a proper position. Improvisation happens in the active battle. If they throw you in the thick of it, there are no calculations anymore.

I never liked math, by the way, but here it is a must. You have to constantly factor in the speed of wind and the nuances of the landscape. Ideally, you adjust for wind after

If they throw you in the thick of active battle, there are no calculations anymore.

Those calculations, do you make them right on position, in the notepad?

Sure. At first you two do recon, without weapons: walk around the place, make preliminary estimates, write everything down, finally return to the base. If there is a need, you adapt your costume to the surroundings. Now, there are standard costumes, the ones you can buy at a shop, but, ideally, you always ought to prepare the camouflage yourself. You can blend into anything starting with grass and ending with a pile of garbage. Whatever your imagination allows.

Approx 650 feet.

Approx. 3250 feet.

What are your battlefield goals?

The priority targets are an officer, a machine gunner, or, with a substantial amount of luck, an enemy sniper. Yet, snipers’ duels are a myth. It is next to impossible to notice a sniper while the active shootout rages on, but even if you do, it is much easier to send the coordinates to your regiment. Artillery, mortars or machine guns will take care of the rest.

What if the enemy notices you?

Abort, immediately. Do not just change your position – go away. As soon as the faces start turning in your direction, this is a bad sign: you’d better hurry up. If you work in the autonomous mode, usually you can do two or three targets at best. Afterwards, the enemy starts looking for the approximate direction of fire. You have about a minute or two before the start of the shelling.

That snipers are not exactly the most beloved people in the army, are they?

It’s the rattest job. The enemy can’t stand you because you cause him a lot of trouble, that’s natural. But occasionally even your comrades keep their distance. If they face the enemy eye to eye or, say, at a hundred meters range, you are situated much further away from the line of fire so the possibility of catching a bullet is much lower

It’s the rattest job. The enemy can’t stand you because you cause him a lot of trouble. But occasionally even your comrades keep their distance.

Tell me about snipers’ rituals. Do you have any?

My personal rituals are mostly practical things. For example, I do not eat before going on position. The only thing I can chew on in preparation for the job is gummy bears or, what’s-its-name, Shalena Bdzhilka [Crazy Bee] sweets. If you munch enough, you do not feel hunger and, importantly, your stomach doesn’t growl. At night, in the middle of the forest, a belly growl can be heard from about fifty meters. For the same reason, I do not smoke for a few hours before work. Smoking kills the sense of smell: a non-smoker can smell a smoker from about seventy meters if the wind is right.

And nobody except complete amateurs notch their guns. Well, some guys do, but it’s really adolescent. A way of bragging.

What do you feel when you strike a person down through the crosshairs?

That’s the most cliché question of them all, so I’ll give you an appropriately cliché answer. You feel the recoil of your rifle. That’s it.

But it still gets to you, eventually?

After the first kill, I threw away my rifle. Right there, on position. Saw everything through the scope, threw the weapon away and cried. Fucking cried. Without shouting or snot, obviously, but I had tears in my eyes, for real.

Why?

I felt it was unfair. The guy didn’t even see me, was just drinking a cup of coffee. I had a great partner, though. He cheered me up, said it was my job. Told not to think about it too much.

After the first kill, I threw away my rifle and cried.

Why did you quit the army, back in 2015?

The targets changed. The job generally stayed the same, but our goals transformed. It’s one thing to see a person with a machine gun and to understand that in a day, or two, or in half an hour, he will be on position, raining down on your comrades. It’s quite different when the criterion you have is the enemy uniform.

Maybe I was wrong to quit. After all, the possibilities for growth in this line of work are almost limitless. You can work on your aim, your skills at camouflage, even your math. I just cut everything off, wanted to change my life radically.

After a while, you realized you have PTSD?

I guess it all started a year after I quit or so. At first I had a heightened reaction to fireworks and loud noises. Then the panic attacks started. I still remember the first one, the most vivid. I was sleeping in my bed at night. Woke up, abruptly, with a thought: that’s it. Now I am going to die. Forgot how to breathe. Did not understand what was happening. The first thing I did afterwards – started googling.

Eventually, the attacks got more frequent, so I worked out an entire system. For instance, eating helps, or chewing gum. If the attacks are really intensive or strike in a public location, you just overpower them with self-discipline.

Did they tell you about PTSD at the boot camp?

Psychologists worked with us back in 2014th. They warned, but I didn’t pay attention – was young and stupid. That’s why after the first attack I didn’t know what was going on.

Back then, everything was quite chaotic, often we had to search for information on our own – in books, videos, even YouTube tutorials.

What helped you, in the end?

An analyst. After a few therapy sessions I felt things were getting better. In our society psychotherapy is still considered something to be ashamed of. In the West it is an absolutely normal thing to do. I am such a fool for wasting so much time. That’s my advice for everyone: go to a psychologist. It’s rad.

Yet, regardless of all this progress, the attacks continued.

And after February 24th?

After the start of the active phase [of the Russian invasion] I didn’t have a single panic attack. It all somehow went away [відлягло]. I feel that now I am where I should be.

Did you return to a sniper’s position right off?

On the next day after the start of the invasion, me and a couple of my comrades procured AKs. In a short while, I got contacted, was handed a rifle, and started receiving assignments. Once again I was told to pick a partner.

Our operation base was in Kyiv, but at nights we would go to the suburbs, where the Russians were staying at the time.

I guess it’s a stupid question, but still: can you even work as a sniper at night?

Of course! You have heat vision sensors, all kinds of devices. Night is an ideal time to do it, really. Though, considering the

Do the implications of your sudden recovery bother you? I mean, sooner or later a peace will come and this type of “therapy” won’t be available anymore.

Haven’t thought about it yet. I am used to living one day at a time. “Plans” is what I used to have before 2014th. So I’ll see. Perhaps, if this helps me feel better, I`ll join a peacemaking mission of some kind.

I once heard a recording of an enemy radio exchange, released by our intelligence services. One of the orcs says to another, you know, if I could, I would have stayed at war forever. I understand him, in a way.

How much [the atrocities at] Bucha changed everything for you?

I always say you have to respect your enemy, no matter what he is like. And I still think that you can respect a person, any kind of person, I really do. But those [Russian soldiers] are not people.

Being a sniper is also considered the rattest job because sometimes you can just watch, you are not allowed to do anything. And what I saw in Bucha, Irpin’… I got emotional. At some point, I was not able to keep my head cold anymore. Not just wanted to kill them. Wanted to make them suffer. And it’s not just Bucha either. Horenka got razed to the ground as did Moschun, two little villages without any [military] significance.

At some point, I was not able to keep my head cold anymore. Not just wanted to kill them. Wanted to make them suffer.

By the way, Moschun. I recall you have a story about it.

So, the fighting in Moschun was particularly intense: at first it got captured by the Russians, then the Ukrainians took it back, then them again, then us again. Because of the constant movement of the frontline many occupants found their final resting place there, in our fertile soils. And the pigs from the neighboring households… Do you know that pigs can eat anything?

Yes, from Guy Ritchie.

Snatch, right. But that’s not a myth. So the pigs from Moschun escaped from people’s sheds, were roaming free through forests, feasting on dead Russians. (Though on our own dead as well, probably.) At some point, they ate all the meat in the woods and started returning to the village. Attacking people in the streets, just like mad dogs. So we were told to go and gun down those cannibal swine.

one of the monickers given to the Russian army by the Ukrainian military and, increasingly often, used by the civilians. Allegedly because of Russians’ lack of tactical sophistication and preference for all-out, overcrowded attacks.

If that’s your most absurd war story, what is the most horrible one?

For me personally it will always be my first… my first liquidation. [He was initially reaching for “killing,” in Slavic languages you can tell by the gender of the numeral.] We were clearing down a village, back in 2014th. He jumped from around the corner, shot at me. I got scared, started falling on my back, clenched the trigger, got him in the chest, neck, chin, forehead, I think. He fell down right in front of me, at a distance of a meter or two. It all happened in a split second, at point blank range.

And the most hopeful?

The way everyone got united. You know, complete strangers write to me on Instagram, send their wishes, words of gratitude.

Doesn’t it get trite eventually?

No way! It’s incredible support. I always make screenshots and send them to guys from my regiment. We exchange them with each other all the time. This is what gives me faith in our victory. Not just as the armed forces, but as a people.

After all these years do you still have fear?

You always have fear, only the fools don’t. And the bold types don’t live long.

Did you know anybody who did not end well because of bravado?

I used to be like that when the war just started, in 2014th. “I am not afraid of anything, I never step back,” that sort of thing. Realized the need to be more cautious only after I caught my first bullet. It got into a bulletproof vest, hit under a shoulder blade. Felt as if somebody smashed me with a hammer on the naked body. You should always keep as close to the ground as possible, not tower above it, turning your head around and all. That’s why I caught it in the first place.

Realized the need to be more cautious only after I caught my first bullet.

As far as I know, in your civilian life you write music for rappers.

It’s called “beat-making.” Mostly I don’t do it for money – work just with performers I like. Not post-soviet A-listers, more of indie guys. This may sound paradoxical, but all my regular artistic collaborators are from the aggressor country.

How do you talk to them? How many of them support the official version of the Russian Federation?

They don’t believe Russian propaganda, but they have this strange sort of view: “I don’t support war but I can’t protest against it because they’ll throw me in jail.” One of them, an especially close friend, confided that he is eligible for draft this year, but that he has already collected enough money to bribe his way out of it. That’s good. It means he understands that otherwise he has a non-zero chance of meeting with me on Ukraine’s territory not in the role of a guest.

Illustrations: Ira Romb for Bird in Flight

New and best