“They Shouldn’t Have Let Me Go After What I’ve Seen”: A Story of One Volunteer Who Spent 100 Days in Captivity

Vitalii Sytnikov was born and raised in Mariupol. He used to work at Ilyich Steel but then decided to follow his new passion for extreme sports and became a rock-climbing instructor.

Vitalii and his family left the city on the 18th of March. In a few days, however, he set off for Zaporizhzhia, where he joined other volunteers who set their course for Mariupol to deliver humanitarian aid and take their things and some locals back with them.

The route was well-known, and the areas where the volunteers were heading had seen no shelling in a long time. The trip should have taken just two days, but the volunteer was captured mere hours after entering Mariupol and spent the following three months in captivity. He told Bird in Flight how he managed to stay alive.

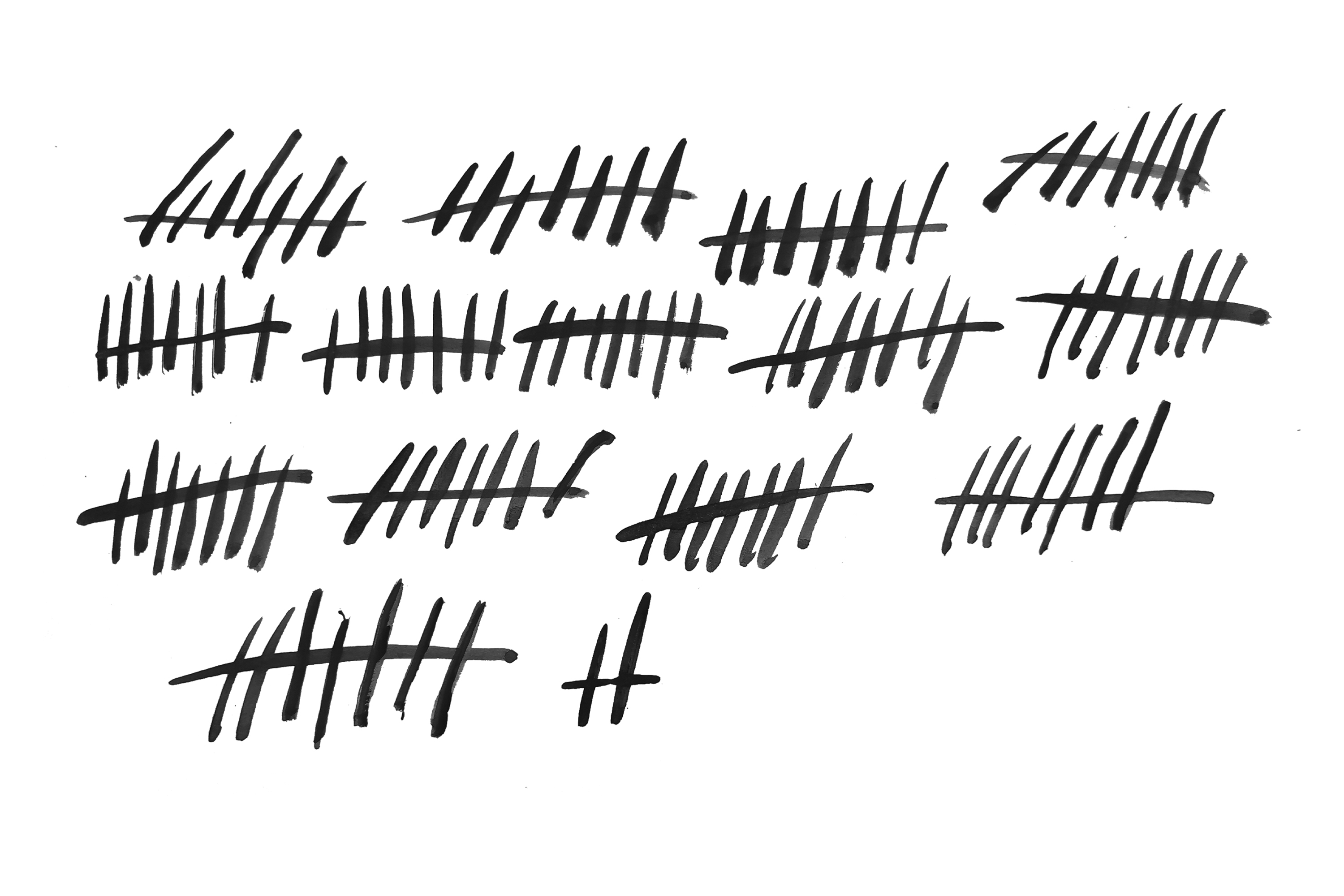

Spent 100 days in captivity.

— There were four mini-buses in our group. We loaded the humanitarian aid and petrol cans, were given all the relevant information, and hit the road. Our plan was as follows: after spending the night in Horikhove, we were to set off for Mariupol in the morning, distribute the humanitarian aid there, pick up people who wanted to leave, and leave the city. Despite the risk of coming under shelling, the route didn’t strike us as dangerous. Everything looked calm in the areas we were heading to.

I was warned that the DPR soldiers at checkpoints inspected mobile phones, but I was prepared anyway — my Instagram and messengers were squeaky clean.

The trip went sideways right from the start. We were pulled over at the very first checkpoint at the entrance to Mariupol. The guy who approached us didn’t buy that we were volunteers and made every effort to find out how much we charged for evacuating people. When we answered for the umpteenth time that we did it for free, he blew a fuse. Swearing and cursing, he threatened to shoot us dead if we didn’t tell him the truth. As a result, he took our fuel canisters and told us to follow him to Mykilske. There, the militants inspected our phones and let us go.

With all that taking some time, we realized we had fallen behind schedule. Seeing that we wouldn’t have left the city before sunset, we decided to spend the night in Mariupol and then pick up the people and leave for the Ukrainian-controlled territory in the morning. We decided to stay the night in the port, which was under Ukrainian Armed Forces’ control at the time.

On our way there, I visited a few addresses to distribute humanitarian aid and gave people a heads up that I would come back in the morning to pick them up. The road was full of holes, and lamp poles lay across the streets. The Russian troops were guarding every junction. We had to stop and hail every patrol, pretending to be happy to see them so as not to raise suspicion. Eventually, our convoy broke — some drivers took a wrong turn, and others didn’t want to wait for me. I was alone.

At one junction, some DPR fighter driving a Daewoo Lanos approached me and told me to follow him. We stopped in the yard of some nine-storey house a few quarters down the street, where a DPR unit was based. First, they stripped me naked and inspected me. Then, they sat me on a chair and started beating me up. The one that detained me kicked me on the head with such force that the contact lenses I wore came flying from my eyes. They threatened me, saying they would kill me if I didn’t confess my connection to the Azov Regiment. All my explanations were in vain.

They stripped me naked, sat me on a chair and started beating me up, saying they’d kill me if I didn’t confess my connection to the Azov Regiment.

When they stuffed me into their Lanos, it was dark outside. The fighter in the back seat near me said: “You twitch, I kill you”. I was positive it was the end of me.

They held me captive for a month without any charges. First, they brought me to the Mykilske District Police Department and then to a few other places. They transferred other captives and me as if we were dangerous terrorists — blindfolded and with our hands tied. The people who convoyed us behaved very aggressively, shouting, spitting threats, and trying to intimidate us. They rarely hit civilians, but servicemen and people connected to the Ukrainian Armed Forces were often beaten up. In one cell, I met a guy who worked as a security guard before the war. The militants tortured him for two weeks, putting a bag on his head and electrocuting him. Mind you, they did it not to interrogate him but for the sake of it.

In one cell, I met a guy who worked as a security guard before the war. The militants tortured him for two weeks, putting a bag on his head and electrocuting him. They did it not to interrogate him but for the sake of it.

Three days after my arrest, I was transferred to Prison No. 120 in Olenivka. It stood empty before the war, and it showed. Sewerage didn’t work, and bunks were cut down for scrap in many cells. I was put into a holding cell. The conditions there were terrible. There were 45 of us in a 15-square-metre room. The air was unbreathable, and you’d have to hold on to something all the time not to faint and fall on the floor. There was no place for sleeping either, so we took turns sleeping on the floor.

Nutrition was a mess. At first, the captors gave us only bread and water (one mug for 45 people) and later some porridge. Also, there was no feeding schedule: the food was brought randomly during the day or at night.

Apart from the inconvenience, two things drove me crazy: a Ukrainian SIM card that I stuck inside my trousers with chewing gum (at the time, I felt I would need it once I was free) and my social media.

Back when the war began, my friends and I prepared Molotov cocktails. Eventually, we decided to check if they worked. We went to a secluded spot, tried throwing a couple of bottles, and recorded a patriotic video that I later posted on my Facebook profile. Setting off to Mariupol as a volunteer, I forgot to delete it. It was by sheer miracle that the DPR soldiers didn’t find it while searching me. While I forgot about the SIM card after some time, that video was always on my mind. Every day, I shook from the thought that some officer could find it.

On the prison territory, we had bunkhouses — long two-storey buildings. Conditions were somewhat better there, with relatively big cells, a separate toilet, running water, some beds, mattresses, and pillows.

Many prisoners were involved in some kind of work. Some typed documents on a computer and others collected personal details of the newly arrived captives. Also, captives lugged around bags full of the things taken from the Azov and Ukrainian Armed Forces soldiers during searches: earbuds, watches, smartphones, golden trinkets, and cash. The bags were many, and they were stored wherever the prison administration was located.

At some point, the prison administration needed help with a computer, so they summoned an IT guy from our cell. He resolved their problem and promised to bring some laptops in exchange for being transferred to a bunkhouse. The laptops came from the company he worked for.

Later, they started transferring civilian volunteers to bunkhouses, too, albeit on one condition: we had to renovate the bunkhouse cells at our own expense to remain there. We agreed. The renovation budget reached $1,000, and one guy procured the entire sum by calling some people he knew on the phone.

Our life in the bunkhouses was much more bearable. We were allowed to go outside, talk to other prisoners, and eat in a canteen with clean kitchenware.

Since they hadn’t charged me with anything, I was sure they would let me go within a month. When my prison time was nearing its end, a guard came and told me to go out. I asked him if I should take my things, and he replied, “Why would you take anything to your execution?” It was his way of joking. The real joke was lather, though. I signed the release paperwork and then another document stating I was sentenced to another month in prison. The resolution said I was charged with terrorism and organizing a criminal gang. That’s where I first realized I won’t be released.

When my prison time was nearing its end, a guard came and told me to go out. I asked him if I should take my things, and he replied: “Why would you take anything to your execution?”

We had just finished renovating our bunkhouse cell. Prison administration drove us out of there, putting us into a disciplinary cell, or “the pit”, as they call it. It was even worse than the cell they put us initially. And then came the moment I will never forget.

The militants searched us while we were transferred, checking our things and even cutting our mattresses open. I rushed to my things, remembering about the SIM card. The chewing gum stubbornly clung to the fabric, and I had difficulty removing it. A guard noticed it and told me to face him. The SIM card finally came off that moment, and I swallowed it before complying with his order. I don’t know what they would have done with me hadn’t I done it.

Beatings were rare in the bunkhouse, and they got much more frequent in the disciplinary cell. Disciplinary cells had bars for walls, so we clearly heard the screams of our soldiers being tortured. It was unbearable. The guys said two of our servicemen died from cardiac rupture.

Civilians had their share of suffering, too. One was beaten dead for sealing a little shampoo. The other was killed for picking cherries from a tree in the prison yard. The more I heard and found out about the life there, the less I believed I would survive.

Without phones, we spent those three months in a total information vacuum. We learned the news from the people distributing food — we called it Hogwash FM. The guards said soon we would have nowhere to return because entire Ukraine would be conquered. However, we refused to believe that. They parked their military equipment just outside the prison walls — they used the facility as a shield, knowing that the Ukrainian military wouldn’t shoot at their people. Their artillery kept shooting all the time, probably shelling Mykolaiv. Apparently, the battles continued.

There was a TV in one of the buildings, and it broadcast channels of the so-called DPR. In mid-June, Ukrainian TV channels appeared — Ukrainian forces must have jammed the signal. Somebody watched the story about volunteers who went missing in Mariupol, in which the journalists even talked to my mum. When they told me about it, I rejoiced. We were not forgotten, so we would soon be released or at least kept alive.

Guards came in the morning of the 4th of July. They said, we will read the surnames aloud, you hear yours — you go out. Everyone was happy, but one of the guards jokingly said, “Hey, what are you happy about? You’re going to Mariupol for manual labour!”

They brought us to the second floor and made us squat. One of the captors approached and told me to stand aside and wait. I thought they saw my Molotov post and got tense. Luckily, all went off well, and I was released.

And so some other guys and I went to Donetsk on our own to get our documents. However, having got mine, I hesitated to return to the Ukrainian-controlled territory. Soldiers at checkpoints still checked our phones and social media, and if the DPR militants saw my post, I would have ended up in prison again. I couldn’t delete it because I forgot the password to my Facebook. My friends did everything they could to help, reporting the post and leaving messages on my feed to sink it down. Nothing helped. In three days, my parents managed to restore my SIM card, log into Facebook on my behalf and delete the video. When I learned about it, I felt truly free.

When a serviceman at the Ukrainian checkpoint entered our bus to check documents, we all started applauding so loudly that it caught him off-guard.

Now I’m recovering and preparing paperwork to get compensation. I could really use some money now that I’m out of work. Besides, my debts kinda mounted while I was in captivity. When I get things square, I will return to volunteering.

Illustrations: Taira Umarova exclusively for Bird in Flight.

New and best