Speechless: Collective War Experience in Dmytro Prutkin’s Photo Project

Kyiv-based photographer Dmytro Prutkin’s project has made it to the shortlist of the Photography Grant 2023, held by the online platform

Curatorial platform dedicated to contemporary photography that started its work in 2012. The platform is also known for its grant program for photographers: the winner receives £30,000 and a presentation at photo festivals.

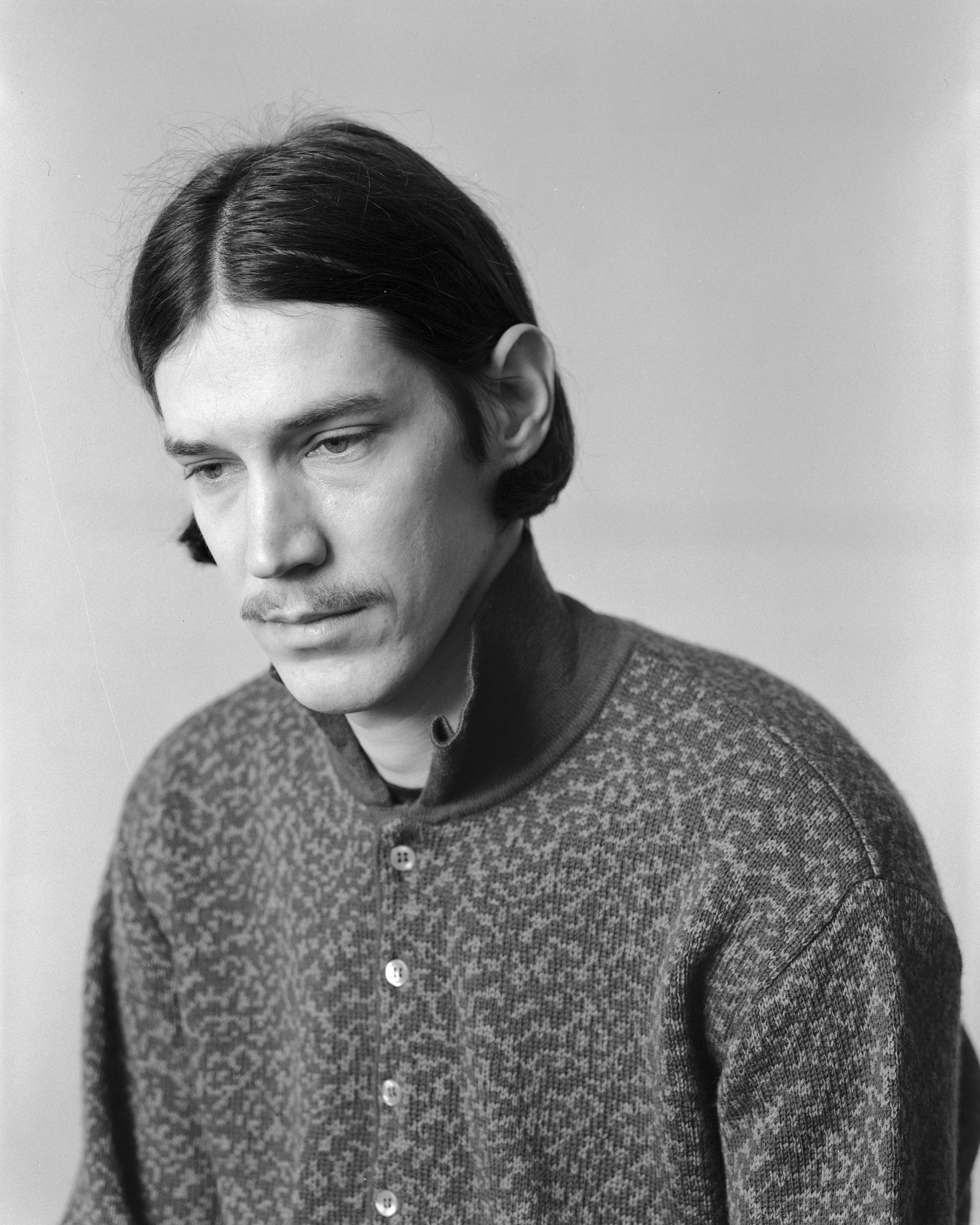

Photographer and researcher. Graduated from Viktor Marushchenko's photography school. Studied documentary film directing at the workshop of Serhiy Bukovsky. Lives and works in Kyiv.

— I was in Kyiv at the time of the invasion. At midnight, I was reading news about what was happening in Donbas: I wanted to find information that would convince me that the invasion wouldn’t happen. And then I woke up to explosions.

In May 2022, I set off for the de-occupied Kyiv and Chernihiv regions. At that time, the battle for Mariupol was still going on, and what I saw in Borodianka made it clear that Mariupol looked the same. I quickly realized that I didn’t want to make a catalog of ruins. Moreover, the local people were tired of media attention – they were willing to talk, but didn’t want to be filmed.

Most of all, I was afraid of aestheticizing the war. Images can be horrifying in content, but too beautiful. After all, when you take a camera, you inevitably think about composition and light. You can easily miss how a photograph turns into war porn, and start looking for increasingly horrific scenes to excite yourself and shock the viewer.

It’s possible not to notice how a photograph turns into war porn.

In addition, I was concerned about how relevant my photographs would be. A random witness with a phone can capture a much more powerful and truthful image, and photographers usually arrive after the fact.

I was confused. Horrible news photos were replaced by new ones and eventually forgotten. It’s harder with what you see in person: you have to experience it. Relief came when I traveled around the region and mechanically did my job. In the matte glass of my camera, I saw an inverted image – a reproduction of reality. This helped me distance myself.

This internal dialogue became an important impetus for the project, and I decided to be honest with myself and the audience. So I started taking pictures of those who stayed in Ukraine. Mostly young people aged 25 to 45. The process was very slow: preparing for a photograph alone could take 15-20 minutes. Not everyone could handle it. That’s why I’m still working on the series, shooting continuously. I plan to make a book out of it.

Last spring, I was given hope by how quickly Ukrainians were rebuilding destroyed homes and returning to normal life, as well as the bravery of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Now there is a great physical and psychological fatigue. Meetings with the heroes of the photographs turned into psychological sessions. Everyone had similar feelings, but they hid them. This insight formed the basis of my series.

Meetings with the heroes of the photos turned into psychological sessions: everyone had similar feelings but kept them hidden.

New and best