To Living and Unborn: The War Archive by Yelizaveta Bukreeva

Photographer. A member of the collective Burn My Eye, specializes in documentary photography. Her works have been exhibited in the USA, Europe, and Ukraine. She lives and works in Kyiv.

— The impulse to create this series was triggered by a combination of various factors. Firstly, the Russian-Ukrainian war, especially after the full-scale invasion, is undoubtedly one of the most extensively documented conflicts in human history. However, I thought that a hypothetical German might not see the same news as Ukrainians do. And it would be understandable because our countries exist in different contexts, but there is one “but”: Russia poses a threat to any other European state as well. Although only Ukrainians fully comprehend this. Moreover, social media algorithms work in a way that we see our own war more frequently than people from other countries. I indeed received feedback from Europeans who were not even aware of certain events. Therefore, it seemed important to me to archive these harrowing news.

Secondly, there has been a significant shift in the demand for war photography over the past 30-40 years. While media previously sought to shock viewers and chose the most emotional and genuinely horrifying shots, now they try to avoid such images. In my opinion, it is crucial to maintain a balance between romanticizing and portraying the real unspeakable horror of war. It is not a topic where corners should be softened.

It is crucial to maintain a balance between romanticizing and portraying the real unspeakable horror of war.

A Russian missile hit a building on Lobanovsky Street, 6a, in Kyiv, Ukraine, on February 26, 2022

Shelling of a public transport stop in Mykolaiv. September 29, 2022

Mariupol, March 2022

The Warsaw Highway in Kyiv Oblast, March 2022

Mariupol, spring 2022

Thirdly, when I was growing up, it was not common to talk about war. You simply did not receive answers to your questions or received ones that did not generate new questions. Did all schoolchildren in the 2000s truly understand what the Holodomor was? I don’t think so. I would like to talk to the new unborn generation of Ukrainians about the war—then I will show them this series.

And finally, I try to explore various approaches in my work and constantly step out of my comfort zone. I believe that not only reporters can document war. I have been following the news all my conscious life, so sorting and analyzing a large flow of information is customary for me. It’s just that now all of it has become traumatic, and its horror is incomprehensible. Physically incomprehensible. But projects are created when the author has something to say.

Not only reporters can document war.

Glass bridge Kyiv, October 2022

Mass graves. Izyum, Kharkiv Oblast, 2022

Cemetery in Bucha. 2022

Executed men in the basement of the city of Bucha, where Russians held local residents hostage. Kyiv Oblast, March 2022.

Medics providing first aid to injured civilians. Vinnytsia, July 15, 2022

Ukraine, 2022

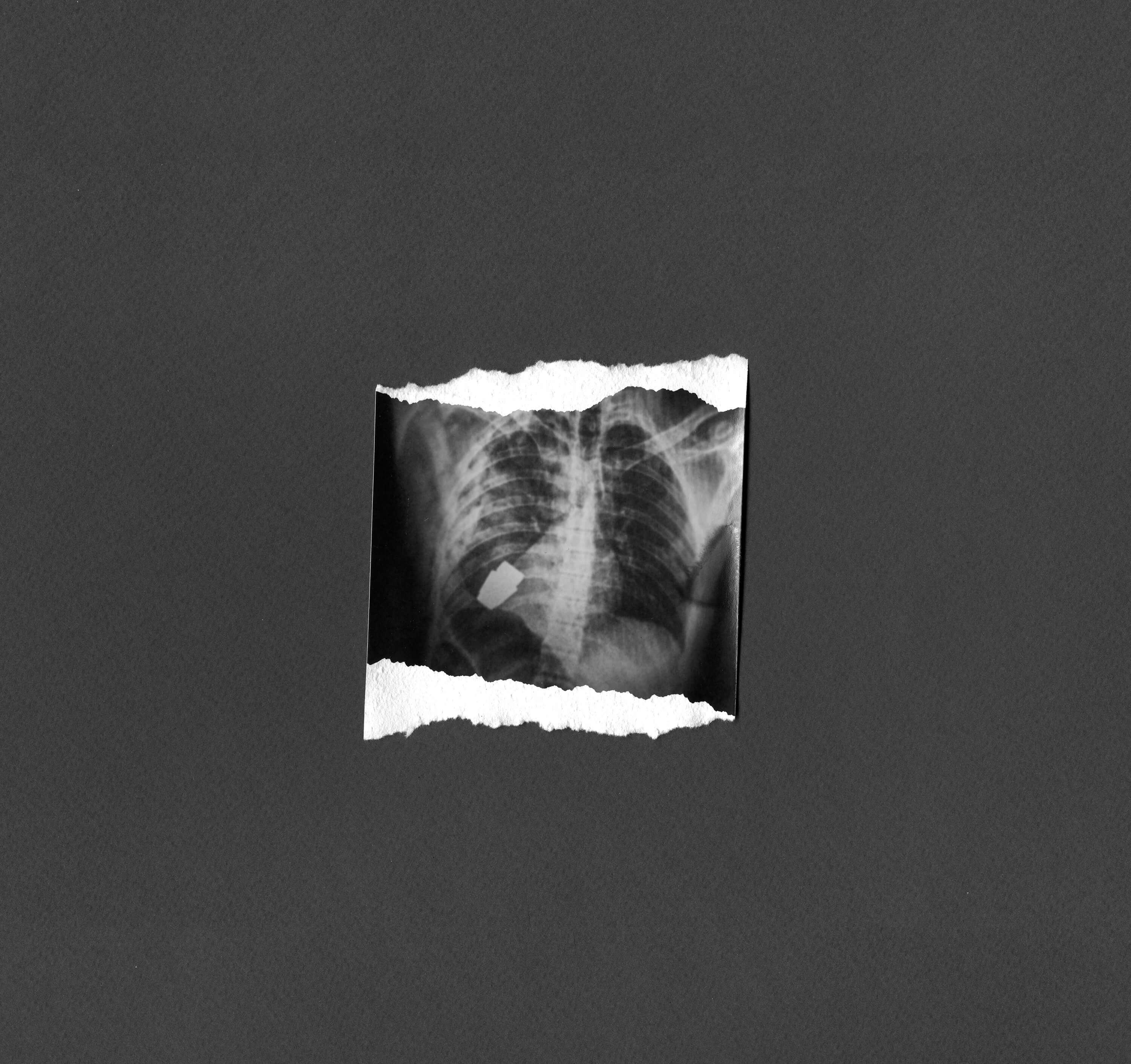

Unexploded grenade lodged in the body of a serviceman. January 2023

Gas mask used for torturing Ukrainians in Kherson Oblast

Technically, the work on the series looks like this: for several months, I collected the most important news witnessed by ordinary people, not journalists. I also used videos published by official sources. Next, I conducted fact-checking, and some content was sorted out during this stage as there was a lot of dubious content in March-April 2022. Then, I took screenshots from the videos, converted them to negatives to manually print from the laptop screen. And the final stage – printing, drying, and scanning. So, these are not captured images but printed still frames from videos.

To be honest, I’m not sure if this work would have existed without the grant from Ukrainian Warchive and my responsibilities to them. The series is still in progress and will continue until the war is over. I actually don’t want it to continue because in this case, the life of the project is equivalent to the real suffering of Ukrainians. I don’t think any museum would dare to exhibit it now. That’s why it’s called “Don’t look at the pain of others.” It’s also a reference to Susan Sontag’s

I actually don’t want it to continue because in this case, the life of the project is equivalent to the real suffering of Ukrainians.

“Regarding the Pain of Others”, first published January 7, 2003

Torture site near Kupiansk. September 2022

Kostiantynivka, May 3, 2023

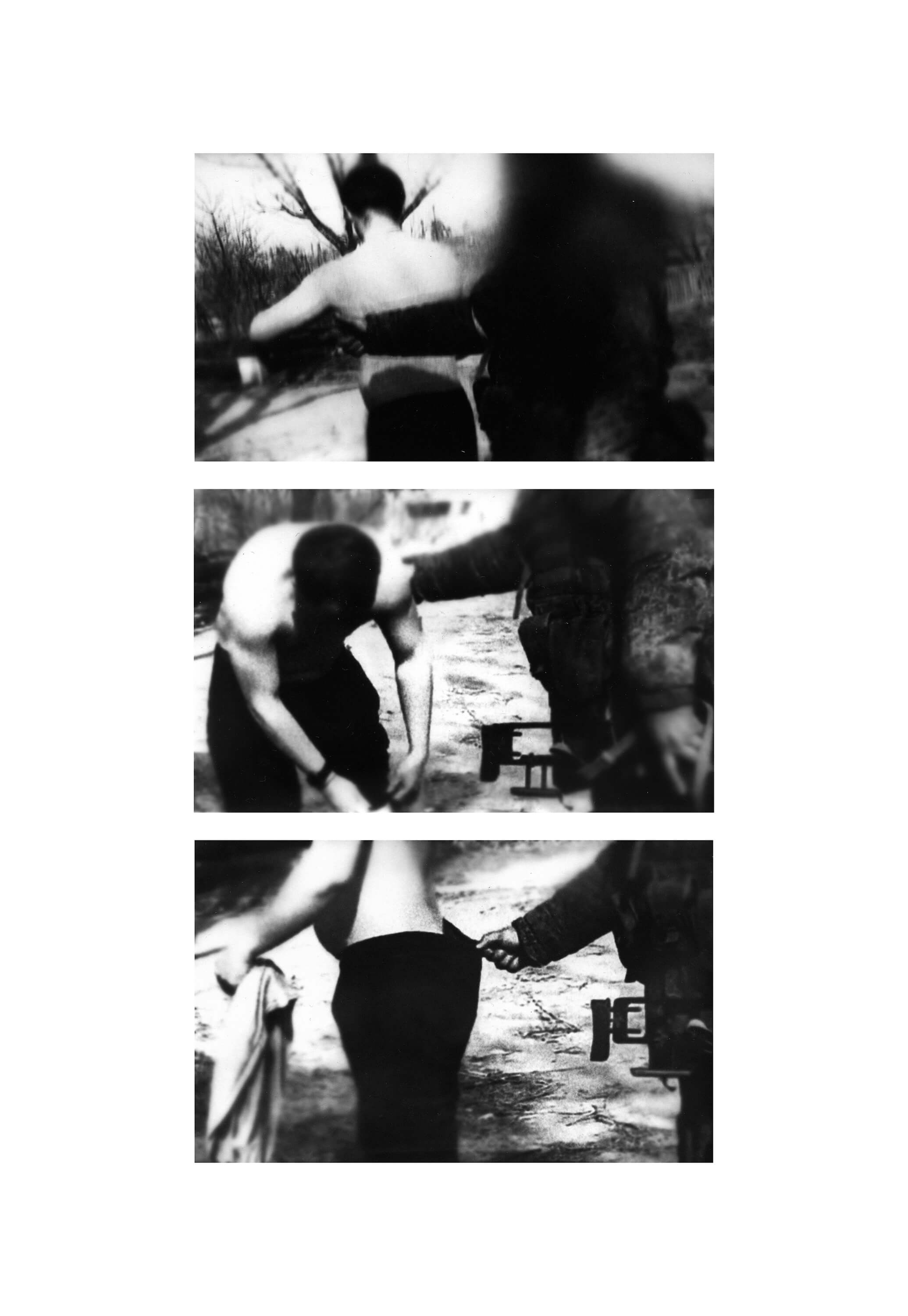

Search of a man by Russian military before sending him to a filtration camp. Mariupol, 2022

Bakhmut, May 2023

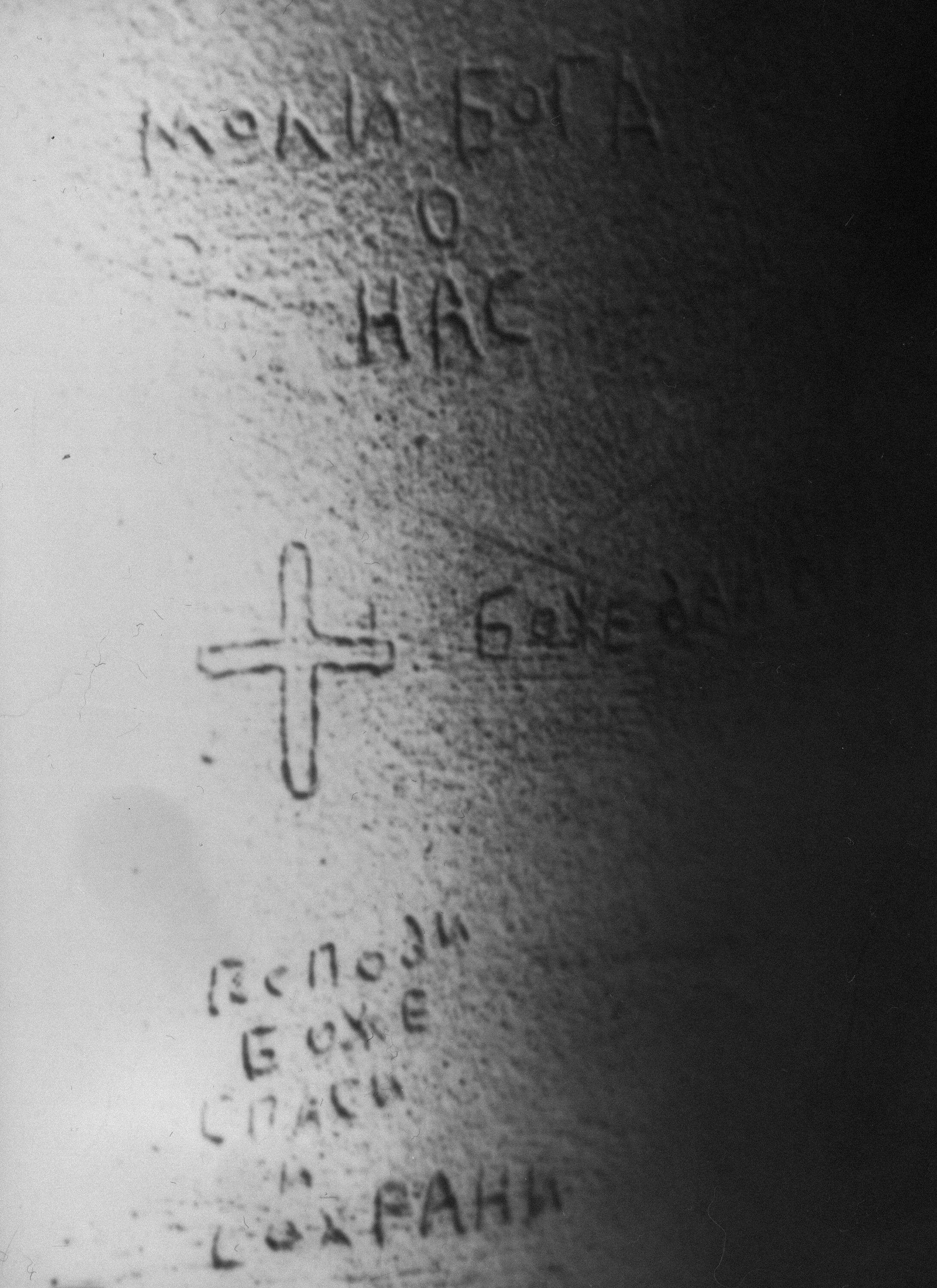

Graffitis scratched by prisoners on the walls of the torture chambers in Kherson Oblast

Kostiantynivka, May 3, 2023

I didn’t choose whether to work on this series. This choice was made for me by the Russian Federation and the conditions in which the modern world exists.

Any, even documentary, photograph is subjective. The viewer can only see what the author included in the frame, the caption they chose; it’s all about the photographer’s choice. In the series, I clearly understand my purpose – to preserve testimonies of the life of Ukrainians in the conditions of war for the yet unborn people. Will they see this project? I don’t know, but they definitely should.

Fired shells. Kyiv Oblast

Ukrainian fields. 2023

New and best