The Capital’s Order: A Guide to Kyiv Brick

Our editorial staff, together with SAGA Development decided to pay tribute to the key building material in the history of mankind – a brick. Mykhail Polovetsky, at our request, has told us what the old Kyiv bricks can reveal, and Olya Sosiura, a photographer, has captured this material in a way that is appealing to look at for a great deal more.

A brick land

A series of construction booms, which took place in the russian empire in the second half of the XIX century, led to the brick production growing. It came to Kyiv in the beginning of the 1880s when the local merchants started purchasing houses to rent apartments. There was plenty of matter for bricks in Kyiv and its outskirts. Light red and small white bricks, suitable for laying out stoves due to their fire resistance, were made of clay procured in Petrivtsi. Dark red bricks were made of the reddish brown one from what now is a modern Obolon district. This clay changed its colour when burnt.

But the top seller was a light yellow brick. Ivan Fundukley, the Kyiv governor and antiquity aficionado, dubbed it the finest one in his book ‘Statistical description of the province of Kiev’. The light yellow brick was made of the blue clay. Due to its water resistance, it was well-placed for Kyiv construction, where there’s always been a threat of the Dnipro river flooding the foundation and the wet soil accelerating the building’s deterioration.

The quality branding

At the end of the XIX century, the brick production was growing at such a pace that the government failed to catch up with all the manufactures emerging all over the country to register them. The product quality control was out of the question.

For long, brick branding was required by the government only in relation to the major industrialists. It was done to foster the customs registry of products export. In 1846, Nicholas I assembled a commission that developed the standards for brick production. Every small detail was scrupulously included: from the requirements for clay and furnaces to the size of the products themselves. It was followed by the emperor issuing a decree obliging all brick factories to put branding on their products, so that should there be a defect, the culprit would be found. Each major production had its own branding.

Large and small plants

There were about three thousand brick plants employing up to 20 people in Kyiv and its province. But the official statistics didn’t count them in – they were of a way too little scale. There were far less large manufacturers. A handbook ‘Kyiv Brick’ claims: in 1845, there were 11 brick plants in the city, 8 of them – private, 2 – state-funded, and a monastery one. The end of the century saw a forty of them emerging. Adam Snezhko, Aphinogen Luniv and Iona Zaicev were among the large manufacturers.

Snezhko and his heirs

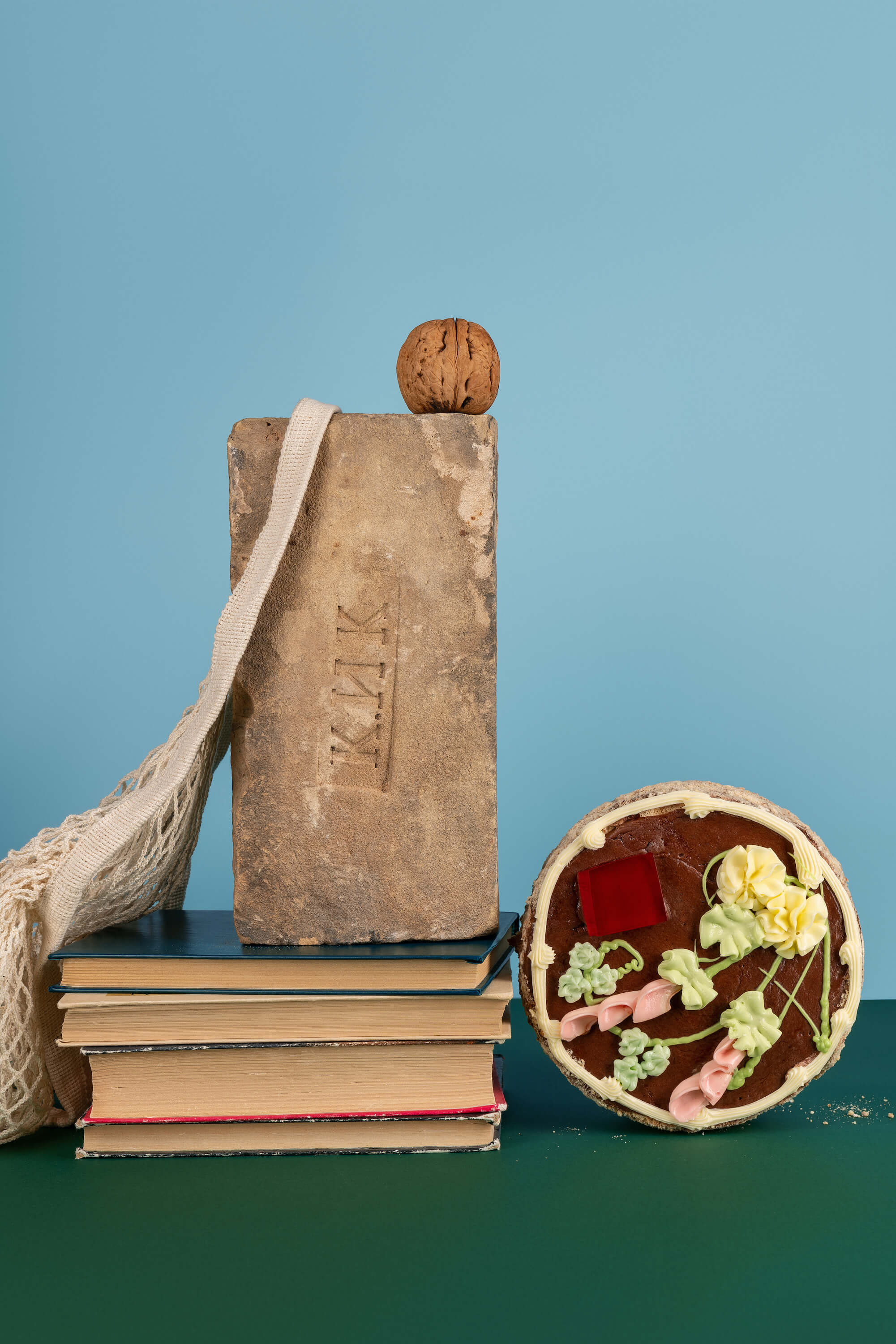

The Snezhko family brick production came out thanks to the Kyiv fortress, which was being constantly rebuilt. Yet another one stage of the building’s modification started in 1830. The city officials didn’t dare to trust private companies with producing building materials for strategic objects, so two state-funded plants took the order. The items they produced were branded «К.И.К.», «К…» (with a year indication) and «КВ». Prisoners from penal military units worked at state-owned factories.

Brick branded «К.И.К.» was used in 1833 to build the fourth fortress tower, located now at 2 Staronavodnytska Street.

Thirty years later, those plants the state didn’t require were bought by the second guild merchant Adam Snezhko, paying 15,780 rubles for them. On Snezhko’s death, the production was divided among his children. The bricks they manufactured were labelled «Н. СНѢЖКО», which stands for ‘Snezhko heirs’. The merchant’s daughter Elena Snezhko took her husband’s surname Khlebnikova after their marriage, and create a separate trademark. Her products were labelled with two logos: a «СНѢЖКО ХЛЕБНИКОВА» (‘Snezhko Khlebnikova’) branding or the letters «С» and «Х» intertwined.

The former tenement house of the Snezhko family, located in Kyiv, 45/2 Pushkinska street (corner of Leo Tolstoy Street).

During the construction boom, Snezhko business skyrocketed, so the entrepreneurs initiated constructing an apartment building, deciding to make it entirely from their own bricks. The building was completed in 1901 and officially opened by Elena. Having survived several reconstructions and the World War II, it has remained to this day. Today one can still see two intertwining letters “C” and “X” on the house facade panel.

«А. С. ЛУНЕВЪ» (A. S. Lunev)

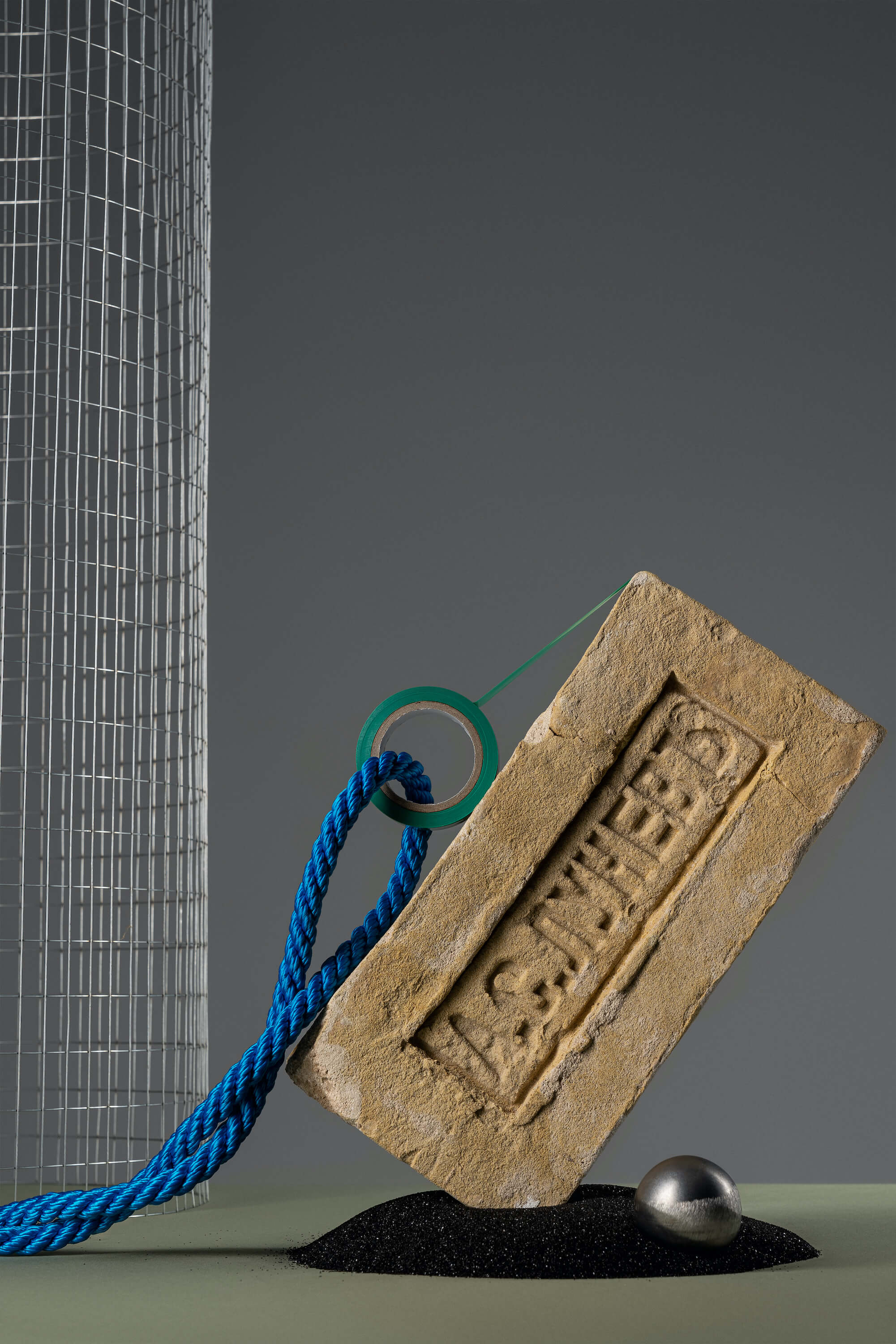

The Kyiv merchant Afinogen Lunev owned brick factories in the village of Mysholovka and in Pyrohovo, but sometimes, like many merchants, he rented other plants.

Lunev’s production was massive. By the end of the 80s, only one factory in Mysholovka was producing a million bricks a year. They were all marked «А. С. ЛУНЕВЪ» (“A. S. LUNEV”).

Lunev’s house is located at 8 Yaroslavska Street. Officially, the building is deemed under construction, but in fact it is decaying.

Little is known about Lunev himself. In 1880, he bought a wooden estate in Kyiv, but soon demolished it so that a brick house could be built in its place. The author of the project was Pavlo Sparro, a popular architect at the time, who built several buildings at Vladymyrska, Prorizna and Tereshchenkivska streets. Lunev built houses from the very bricks he manufactured. The rest remains unknown. Two years afterwards, he sold the property to a Kyiv official.

After the merchant’s death, his heirs inherited the production, Fedor and Kuzma brothers. Lunev branding was replaced by a complex one – «Ф. и К. ЛУ (БР) НЕВЫ» (“F. and K. LU (BR) NEV”).

The most famous plant in history

The Kyiv brick factory of the first guild merchant, Iona Zaitsev, was located between Kyrylivska and Verkhne-Yurkivska streets. But the company didn’t go down in history thanks to the bricks. It was there that Menachem Mendel Beilis worked, who was accused in 1911 of the ritual murder of the boy Andryusha Yushchinsky. The body was found on Yurkovitsa, not far from the plant. In 1913, Beilis was acquitted.

The Iona Zaitsev’s plant address is not quite known. But the former administrative unit of his hospital is located at Kyrylivska, 61. Most likely, the building was built of bricks made by the merchant.

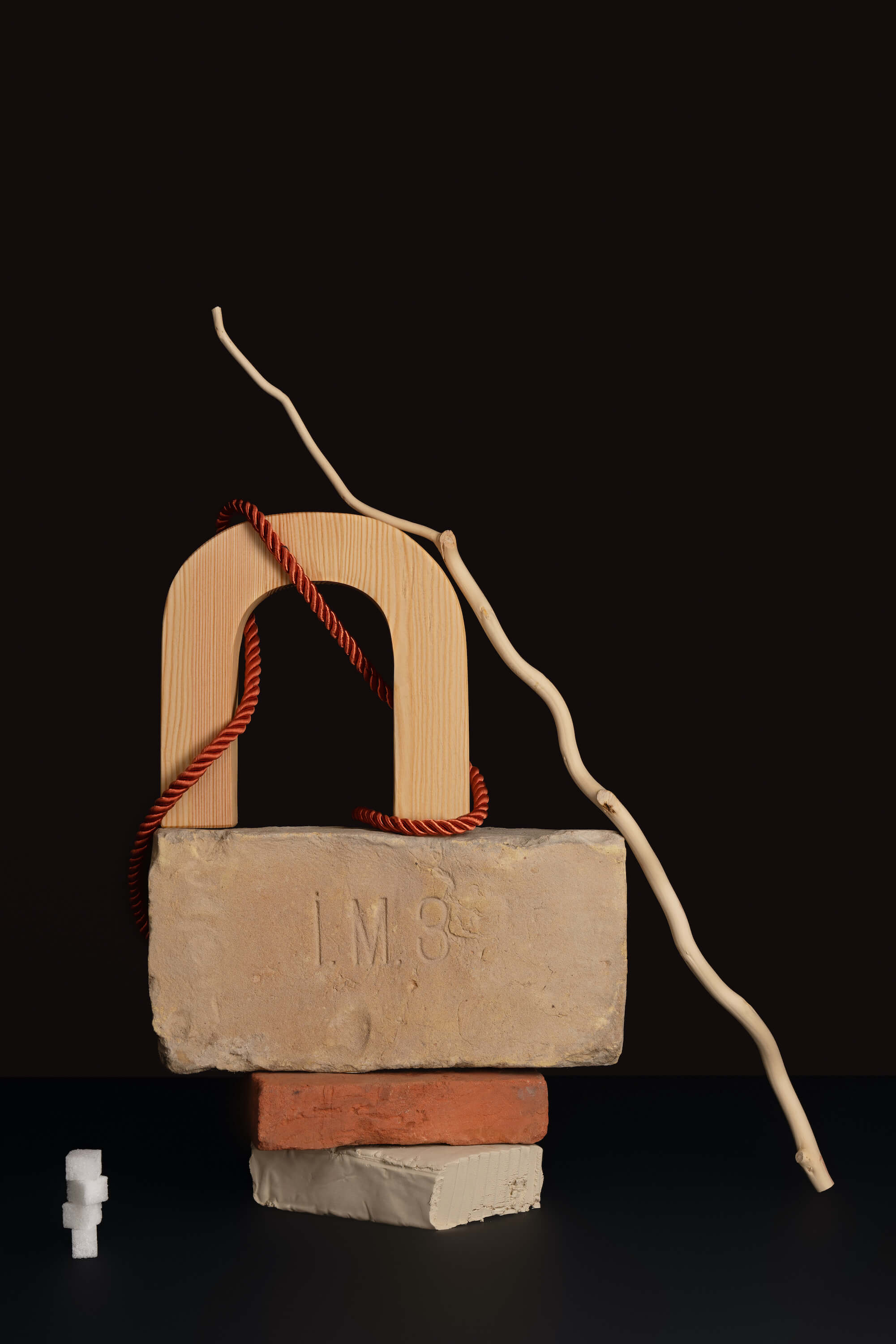

Iona Zaitsev made his fortune in sugar production, and he is recognized as a philanthropist and a medical institutions’ custodian. In 1893, he founded a small surgical hospital, and four years later he built a surgery unit at Kyrylivska, where poor Jews and some others could get a free service. Zaitsev did not witness the Beilis trial – the entrepreneur died back in 1907.

There was a manor and a brick factory near the Zaitsev’s hospital, which belonged to the Kozelets merchant Ignat Bagreev. In 1899, Zaitsev bought both a house and a plant from Bagreev. The bricks produced there were branded «І.М.З.» and «І. М. ЗАЙЦЕВЪ» (“І.M.Z.” and “I. M. ZAYTSEV”). Production was not just a simple business, but also a charity – Zaitsev provided employment to poor Jews.

The Soviet brick

On occupying Kyiv in 1920, the Soviets began not only reconstructing, but also transforming the industries structure. The brick plants were nationalized, their branding – simplified, at times completely changed to a mark of a five-pointed star. The images on bricks were totally gone after the World War II.

One of the buildings constructed in the early 1950s of the new bricks at the time – the silicate ones, – which is now at 16 Vyshgorodska Street.

The first half of the 50s in USSR began with a postwar construction boom, panel houses being the major innovation. The bricks were still in use, but not as en masse as it used to be. Their manufacturing technology had also changed: a silicate brick emerged instead of the ceramic one. It was pressed out of sand and quicklime, that’s why it was cheaper. A red brick continued to be in use for foundation construction as it is more water resistant.

An irreplaceable material

Half a century ago, it was thought that the panel houses were the future. Unlike brick ones, building them is faster and cheaper. Such a vision turned out to be accurate to some extent: today typical buildings are assembled in parts on site or at the factory – or entirely cast on the construction site. It was possible to cut production costs with the help of modern technologies, but it turned out to be impossible to completely replace the brick. Developers still use it to create unique projects.

Brick is especially useful in areas with historical buildings – Podil in particular. When building there, developers must meet two conditions: reject pseudo-historicism and fit the object into the old architectural ensemble. You can accomplish it with bricks. For example, to lay out a modern facade from old bricks: the decayed buildings are dismantled, the bricks are cleaned, restored and reused. This is how the brick part of the facade of the Theater on Podil was created.

SAGA City Space building, located at Petra Sahaidachnoho St, 18.

The facade of another Podil building, Saga City Space, was made by the developer Saga Development out of a new Belgian clinker, having similar colour to the typical Kyiv brick. But this clinker also has its own history. It is produced by the Nelissen company, being on the market since 1921 – the descendants of the Nelissen family still own the production. The brick for the Podil building was part of the idea: it was laid out in such a way as to allow light to pass inside the house during the day and outside at night.

Another way to fit a new building into a historical ensemble is using facade tiles that imitate bricks of the preferable colour. It is made of clay with the same technology as bricks. For example, the condominium complex CHICAGO Central House has its building image created by the Finnish facade tiles Tiileri – they are produced at a family brick factory founded over 50 years ago.

Condominium complex CHICAGO Central House, located at 44 Antonovycha Street

Photo: Olya Sosiura, exclusively for Bird in Flight

New and best