“Beauty Should Come Back as a Goal for Design”: Stefan Sagmeister on Work, Inspiration, and Happiness

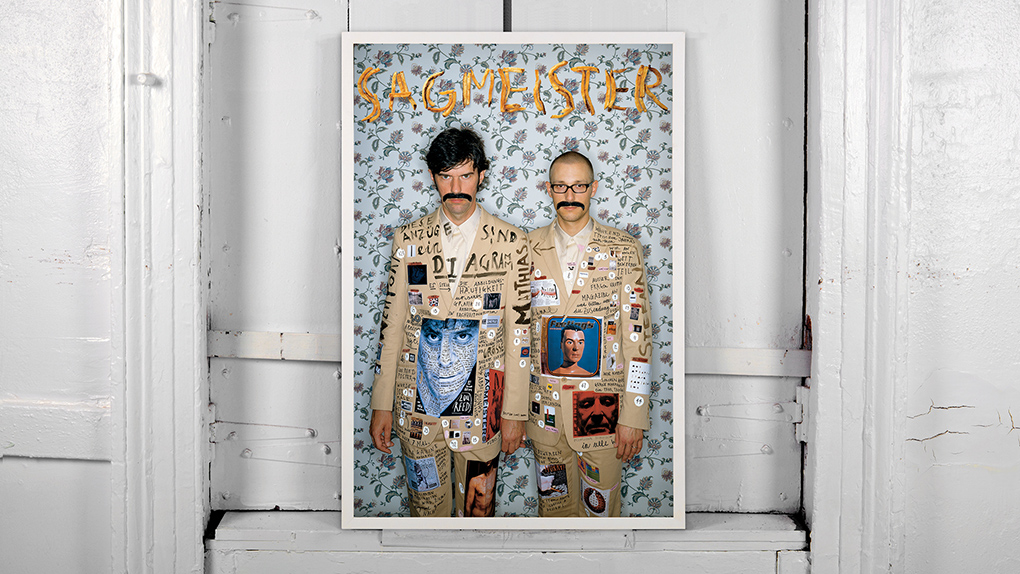

Stefan Sagmeister from Austria started as a designer, at the age of 15, with the local youth magazine called Alphorn. In 1991, he got a job at the Hong Kong office of Leo Burnett’s, the world-famous advertising agency, and two years later opened his own studio in New York City, Sagmeister Inc. (now Sagmeister & Walsh). His company took on everything — from music album covers to corporate identity design. His clients include HBO, The Gap, BMW, and Guggenheim Museum.

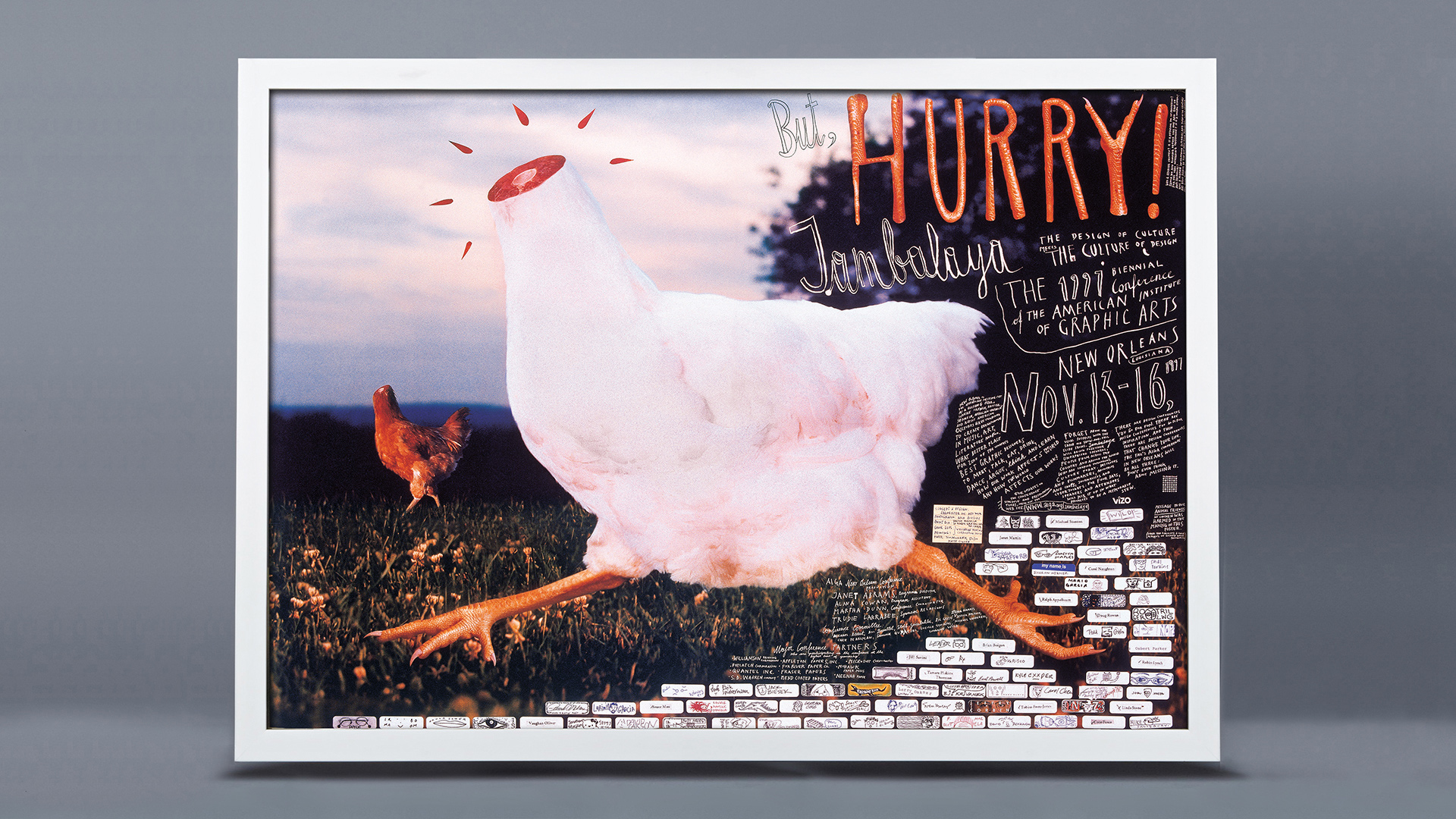

In 1997, an advertising poster with a beheaded chicken brought Stefan, 35 at the time, his first award and an unofficial title of ‘design exhibitionist’, agent provocateur, and a rock star of modern design.

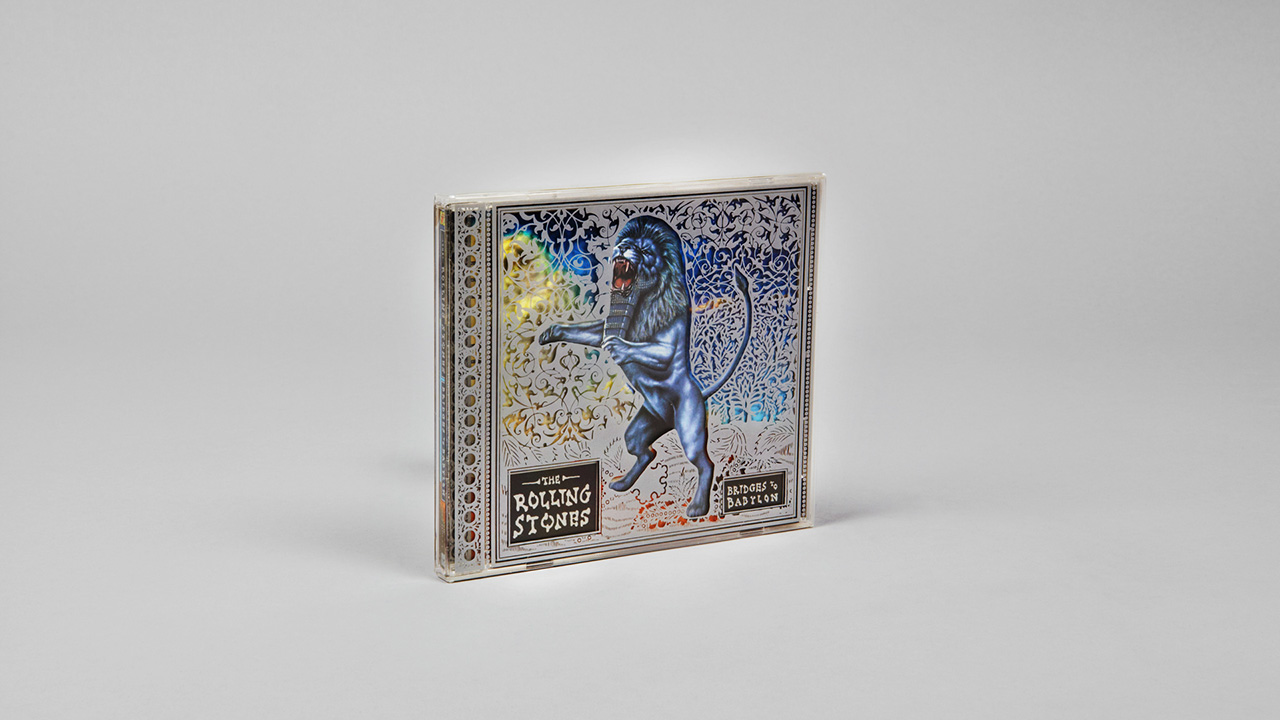

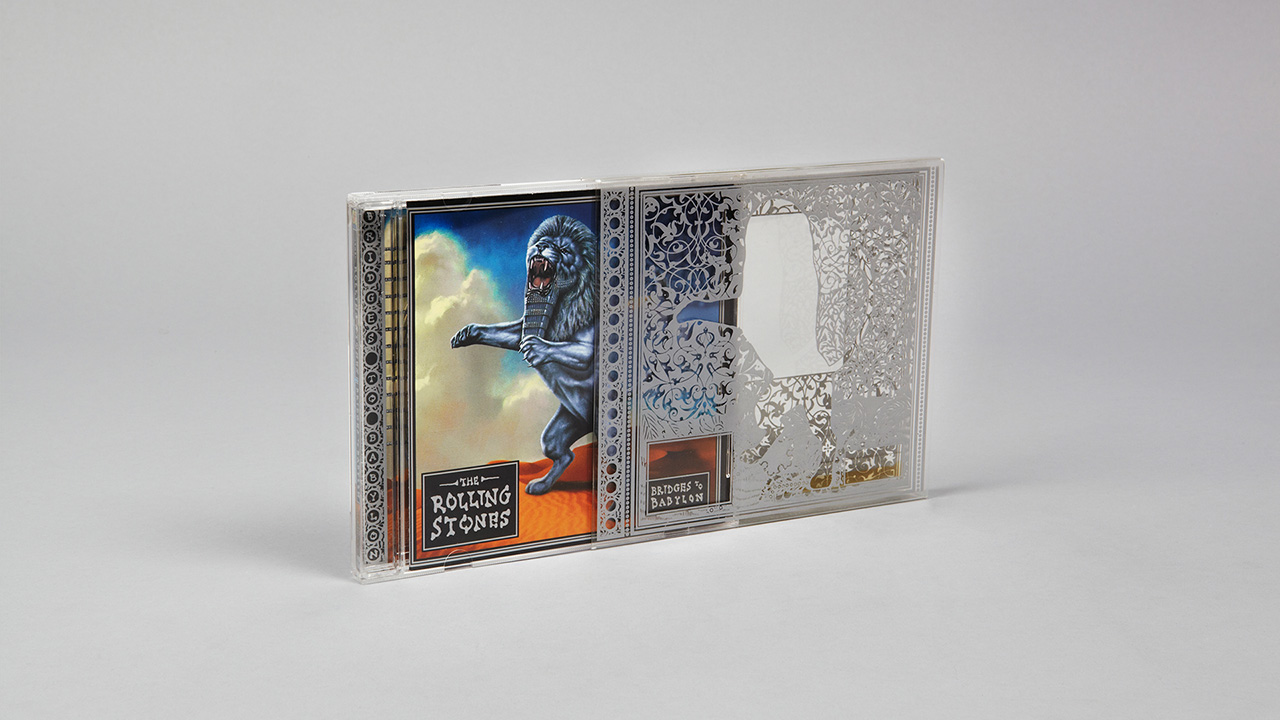

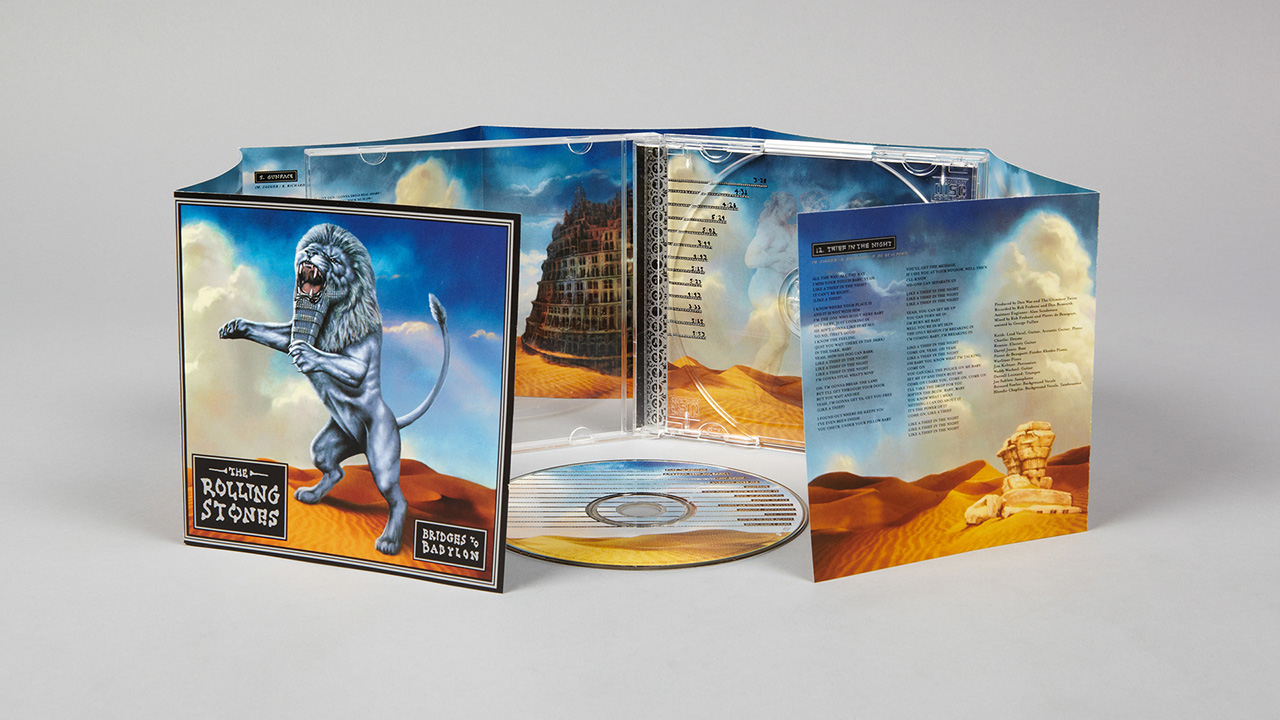

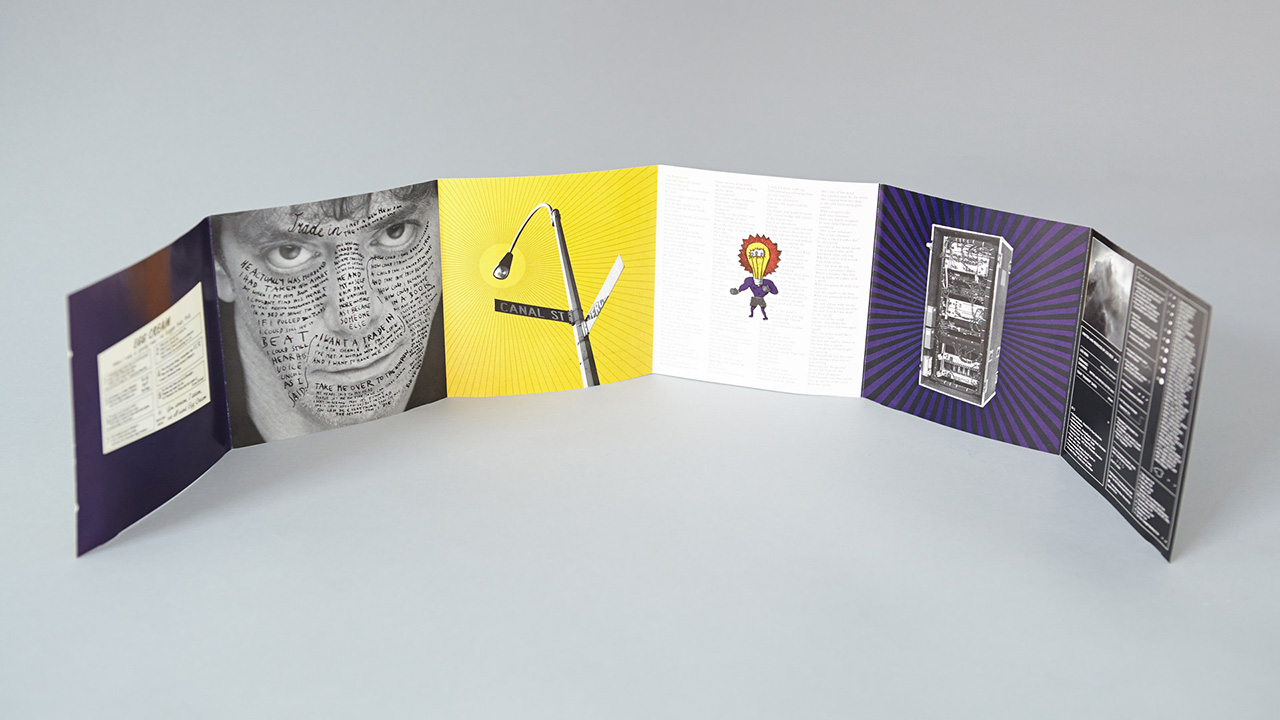

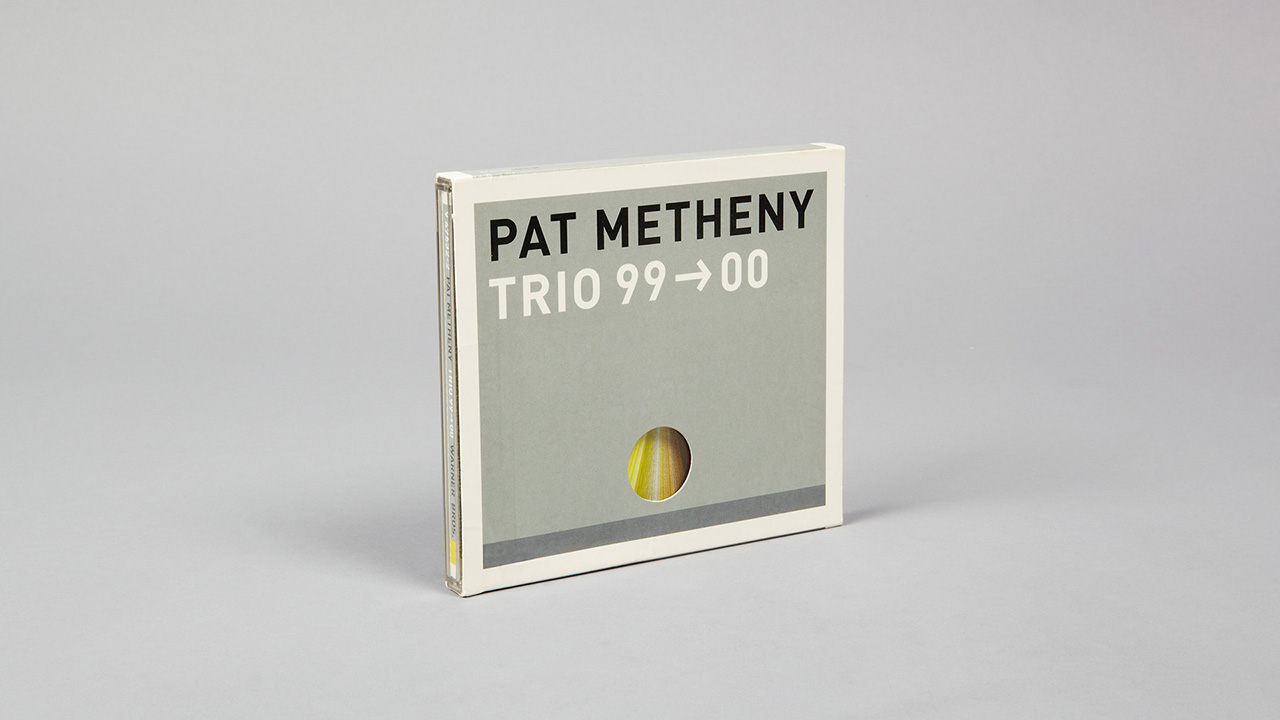

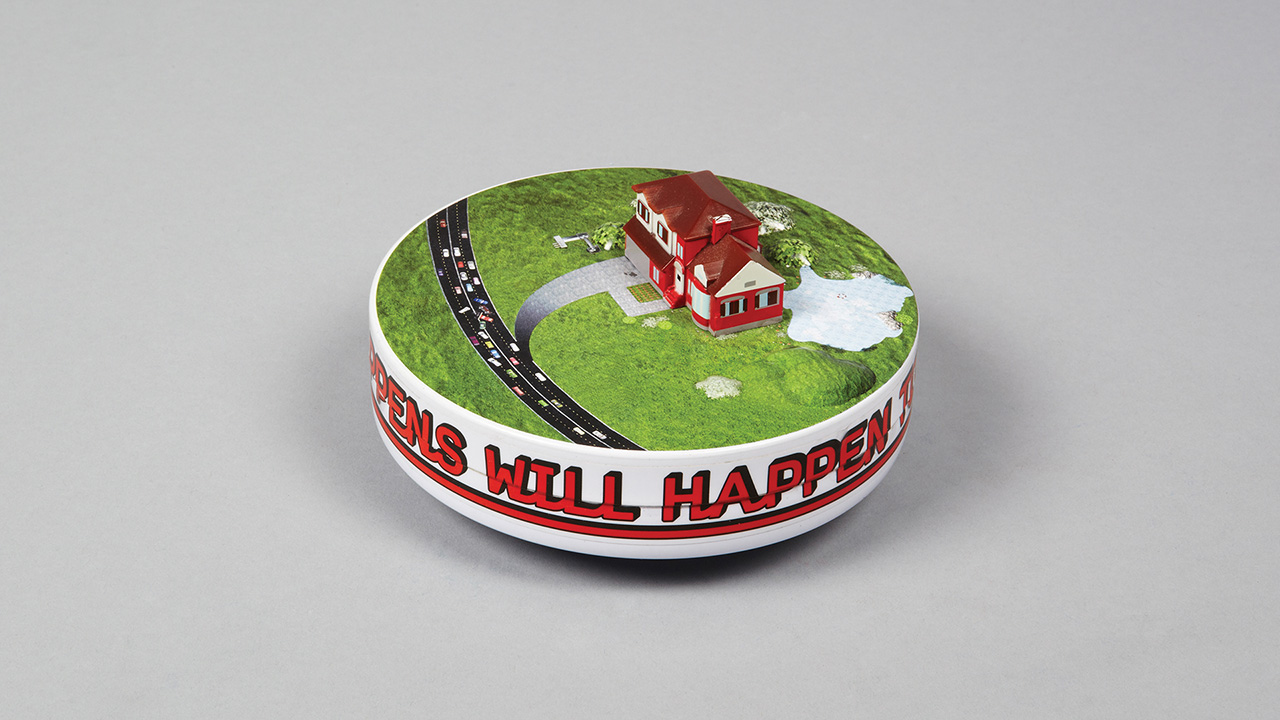

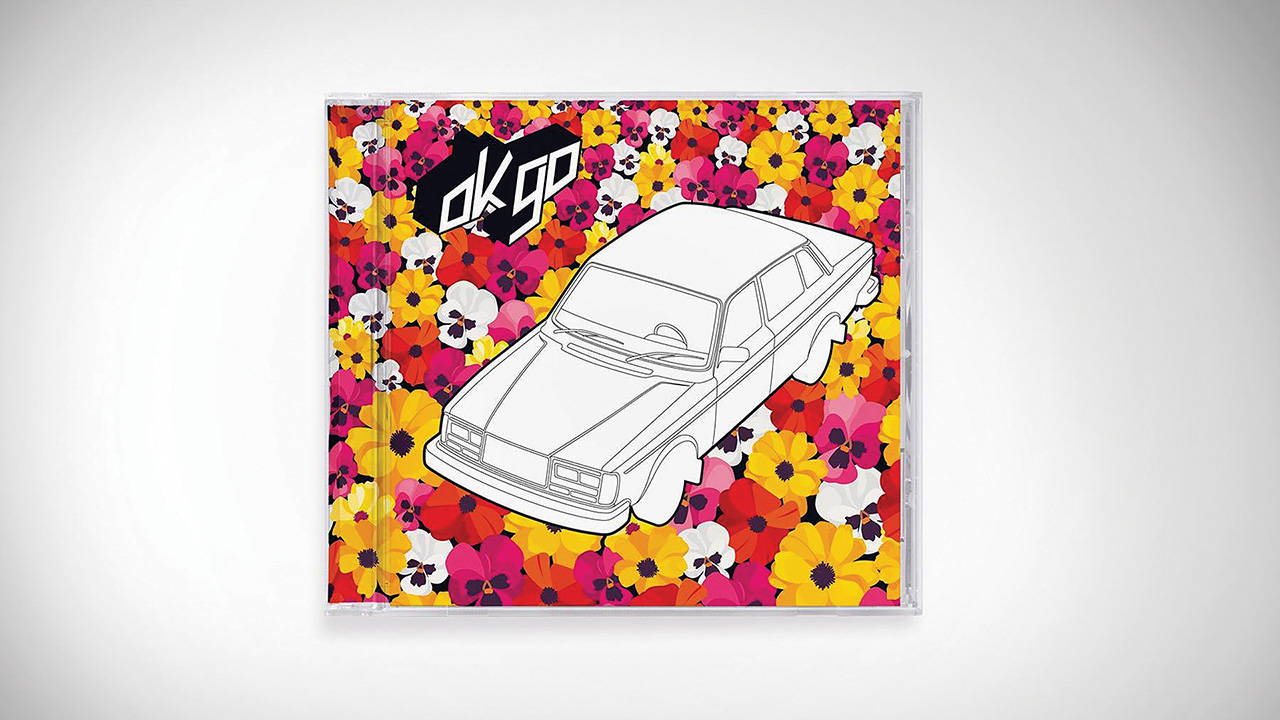

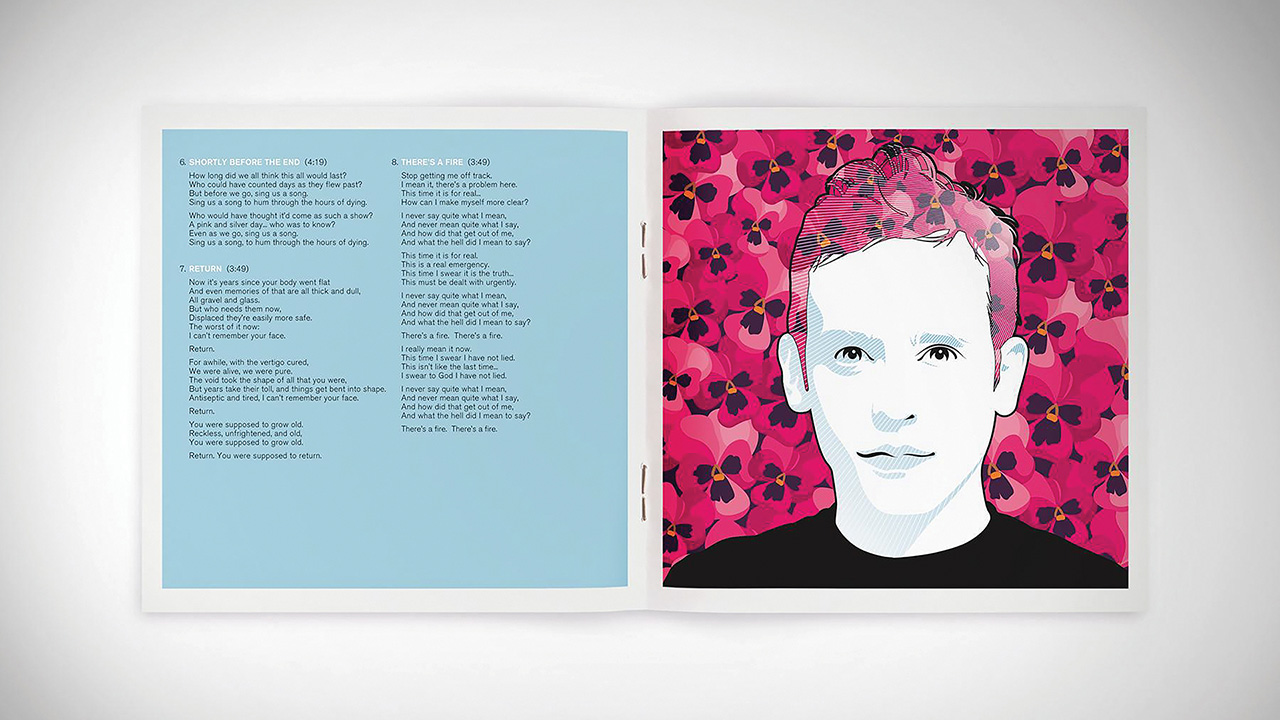

Stefan’s covers can be found on the albums by Lou Reed, The Rolling Stones, OK Go, David Byrne, and Patrick Metheny. He received two Grammy Awards for work on the covers for Once in a Lifetime by the Talking Heads and Everything That Happens Will Happen Today by David Byrne and Brian Eno.

In 2010, the iconic designer decided to try a new role and co-directed The Happy Film, which premiered in January 2017.

You’re a world-famous designer, how does it impact your work today? Do you feel a lot of pressure from so many people watching you?

I normally don’t feel the pressure. I really don’t. I would say that by and large it only comes with advantages and very few disadvantages. For instance, right now we are preparing a big exhibition, and if I now write to a museum, I normally get a reply. If I had written to them 15 years ago, I probably would have gotten no reply and the exhibition would have remained only an idea.

But because the studio is now better known, we get the chance to implement our ideas. On a more personal level, I’ve just spent 4 months in Mexico City and every day somebody recognized me in the streets. Mostly people said something like “Oh, I love your work!” or “Hey, you’re Sagmeister!” — that was nice. And it doesn’t happen so often — I used to work with really big rock stars who are real celebrities, and I would say I would hate it if I was as popular as they are, it would become annoying. But in graphic design, people don’t approach you that often, so it’s actually quite lovely.

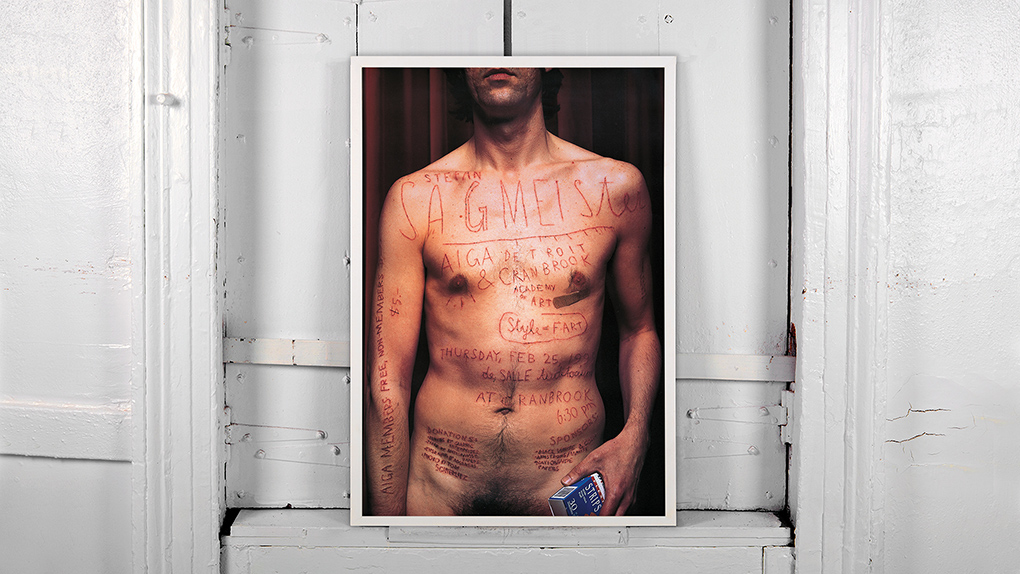

You got your first award for a poster with a running headless chicken. How do you feel about it now?

I would say this: there were a number of projects that we worked on for a very long time, until the point came where I felt that I can’t make it better anymore. And that poster was one of those things. It doesn’t really look it, but hundreds of hours went into that poster and from that point I still appreciate it.

I wouldn’t wanna miss it. I haven’t shown it in a talk in 20 years, I think. I would have to check if it’s even on our website. But a year or two ago, I went into a design office in Amsterdam and they had it framed there. And I got a kick out of it — this poster was made in 1997, and it is still hanging on somebody’s wall 20 years later. So I’m very fond of it.

“As it reads in tiny squiggly type on the top corner of this poster for the National conference of the American Institute of Graphic Arts: Why a headless chicken? Is it a metaphor for the profession?” Image and caption: sagmeisterwalsh.com

Do you have any past work that you dislike now, that you now think has no style?

Sure, yes. We did a lot of bad work. What I definitely remember, in the 90s we did some packaging for games — and I was not a gamer. I like them, but it’s not my hobby. I couldn’t judge if those games were good or not good. And we did packaging for an audience I didn’t really know. And so there was a mistake.

Did the audience end up liking it?

No, it also turned out that the games were bad. If I was a gamer, I would have known it and would have said ‘no’ to the customer. So, since then we try to take on jobs that we either would use ourselves, or if we have a pretty good idea that they have a right to be there.

Have you got anything scheduled for 2017?

Yes, we are working on a big thing on the beauty of human made things — in design, architecture, art. It’s an argument that beauty should come back as a goal for design.

Can you be somebody else aside from a designer? If you ever decide to give up design, who would you be?

I think that design is pretty much the thing I was put on this Earth for. We sometimes go quite far away from design — we did furniture, we did a film. But it is still all centered in graphics. When we do furniture, it’s graphic-y furniture. If we do a film, it’s a graphic-y film. So I think I’m very comfortable in the world of design. I also think it’s a very kind world, meaning that graphic designers (in the widest sense — interface designers, poster designers, etc.) are by and large supportive of each other. A gathering like this would be very unusual in contemporary arts.

You take a year-long break from your studio every seven years. What do you do instead?

I do work in that year, but I only work on projects of my interest, I don’t work on any clients. And I find it very necessary and inspiring for myself, because if you have a year to think about something, the outcome will be very different from if you have just a weekend. You can think about much bigger projects, you can work much more intensively and be more involved.

The second sabbatical, I had many people joining me, so we were like six or seven people working together, but always the same rule — no client projects.

During your year out, do you stay in one country or do you travel?

It’s always different. The last time I was in Bali, I stayed for the entire year. And this time I have three different places — Mexico City, Tokyo, and then a tiny village in Austria.

So right now is just one of those years, isn’t it?

Yes. I’ve been in Tokyo right now.

What do you do on a working day when you feel uninspired? When you just have to work — no vacation or weekend to help you out.

The easiest thing is that we always have roughly three or four projects, so I can switch between them. In total, there’s always about a dozen running, but I’m really only involved in the beginning of the project, so there’s always only 3 or 4 that need an idea or a concept to move forward.

Then, I travel a lot, and I find traveling quite inspiring. Just today I got up at 6, smoked a cigar in front of the hotel, asked them for a coffee to take out — I was just looking around Kyiv and I was so excited to be in a place where I’ve never been.

And I find it very easy to work on ideas when I’m not in the studio, because I can think of an idea that I don’t know how to do, I don’t immediately have to implement it.

Can you name three unknown designers who are doing a good job?

Sure! One would be Zipeng Zhu. He is doing very colorful work, very well-animated and beautifully conceived. I would also say, Richard The. He used to work for Google, but now works for himself in a company called Green Isle.

And the third is not unknown, but the much underappreciated Joachim Sauter. He has a company called ART+COM in Berlin and he should be world-famous and I have no idea why he isn’t. He is known in Germany, but not very well-known around the world. They do interactive haptic design — maybe one of the most famous things they did was an installation for BMW, these spheres coming down from the ceiling, and it was absolutely gorgeous.

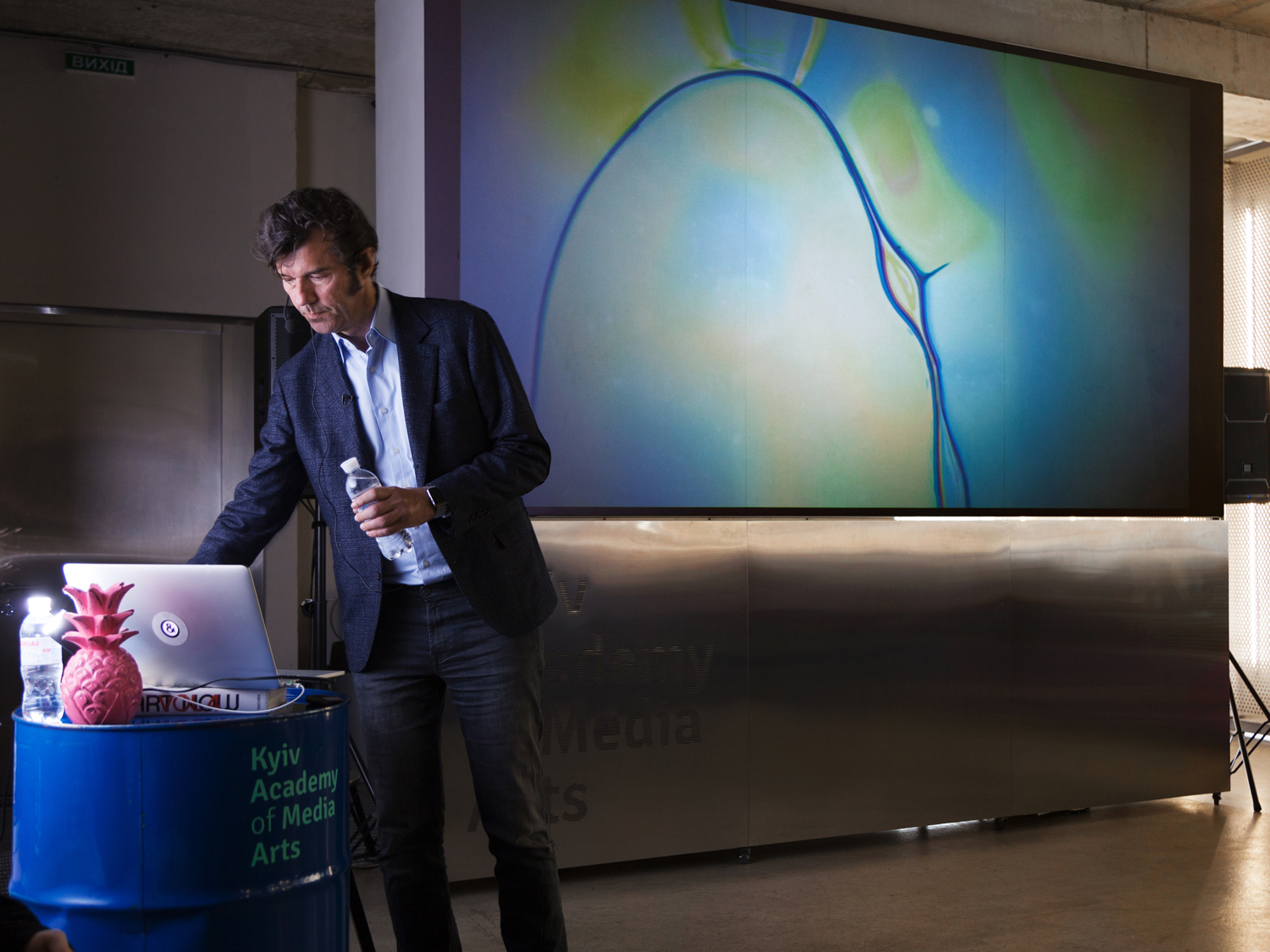

The Happy Film (2017)

A movie, where Stefan alternates between meditation, cognitive therapy and drugs, in a quest to become happier. He records a video diary and measures his subjective happiness, to calculate an average happiness score for each method. The movie took 7 years to make. Ukraine is one of the first countries where it will be screened.

You shot your movie with yourself as the lead actor. How did it feel to be constantly in front of the camera?

Well, it was a big problem. The fact that I was central to the film was by accident because originally it was meant to be a movie about happiness in general, and that turned out to be impossible because the subject was so big that we could not handle it. I was not an expert on happiness — I did not study psychology, I was not a famous psychological researcher — so we decided to narrow the subject and have it be about my own happiness, because on that I am an expert. And then of course it took me a while to understand that it also means it is going to become a movie about me.

It was the first documentary movie we made. I didn’t know that, but other documentary filmmakers told me that an essay movie is the most difficult thing to do, and if you do a personal essay film — it’s even more difficult. That dual role being a co-director and also being the central character was difficult. Actually, while shooting it was okay, because I got used to the camera and it wasn’t a big deal anymore. But in editing it was very difficult, because you make decisions also on at what point does it become oversharing — where is that point when you reveal things that nobody is interested in and it becomes like a reality TV drama.

Are you happy with how the film has turned out? Does the picture you had in your mind fit with the final result?

Not at all, because we very purposefully didn’t have a picture in mind. Originally, I wrote a script and as soon as the script was done we threw it out. We purposefully wanted to make a film where we don’t know the ending. And that again was an entirely new experience for me, because normally I make a tight sketch and we design it until the product finally resembles the sketch.

And with the film we had no structure. We knew that we will do the experiments — meditation, cognitive therapy, and drugs, but besides that we had no idea. But now that the film is out and I can now say I’m happy with it.

Did you manage to become happier? Did you work out some mechanisms, an algorithm for yourself?

Strangely — yes. Very odd mechanisms. Originally, of course, one of the reasons to make a film was the chance that through the research I would become happier. And that didn’t happen that way. I would even say that in many cases working on the film made me unhappier than working on our commercial work. I procrastinated on the film much more than on our client work (laughs) and the reason for that was that I didn’t know what I was doing.

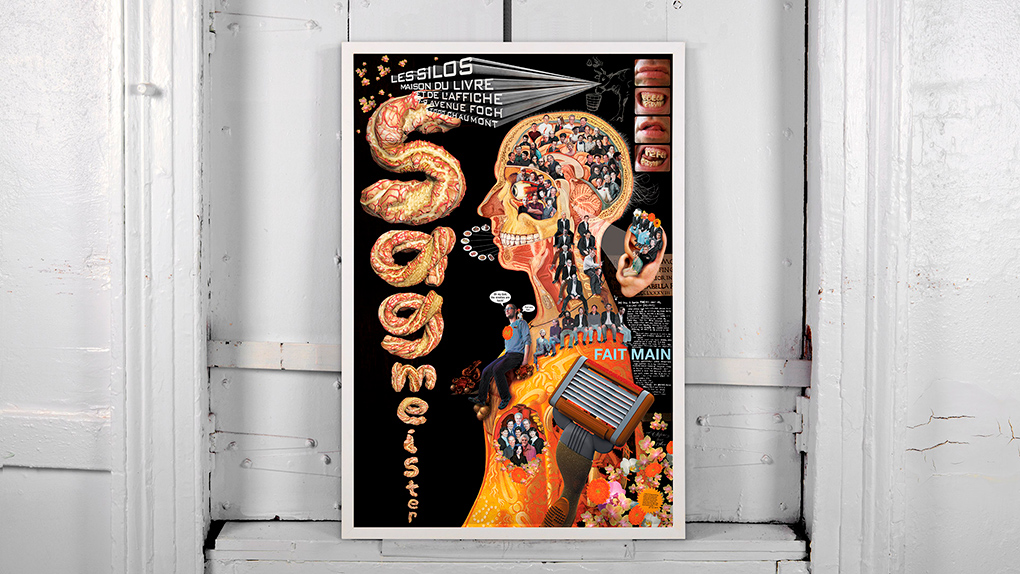

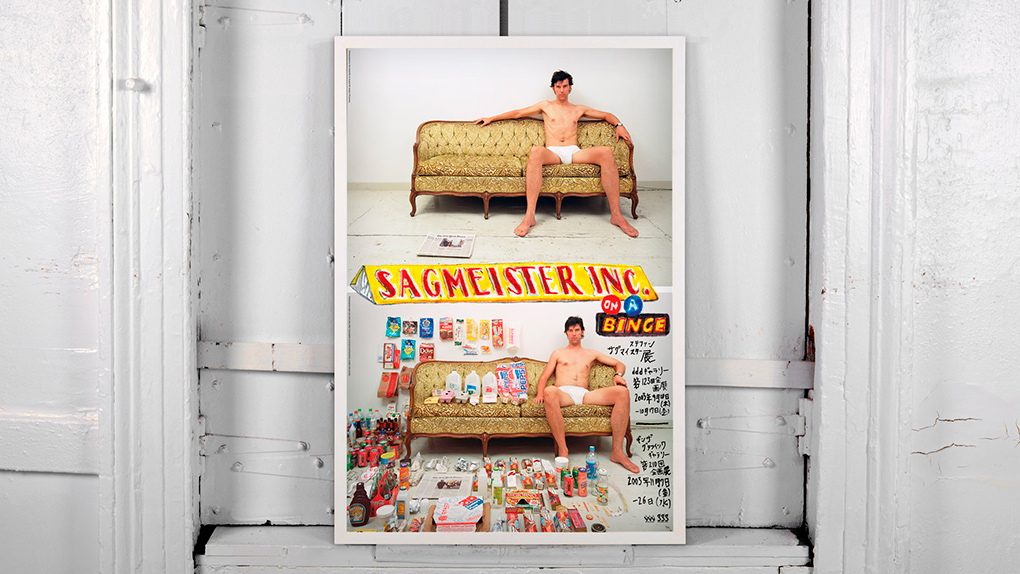

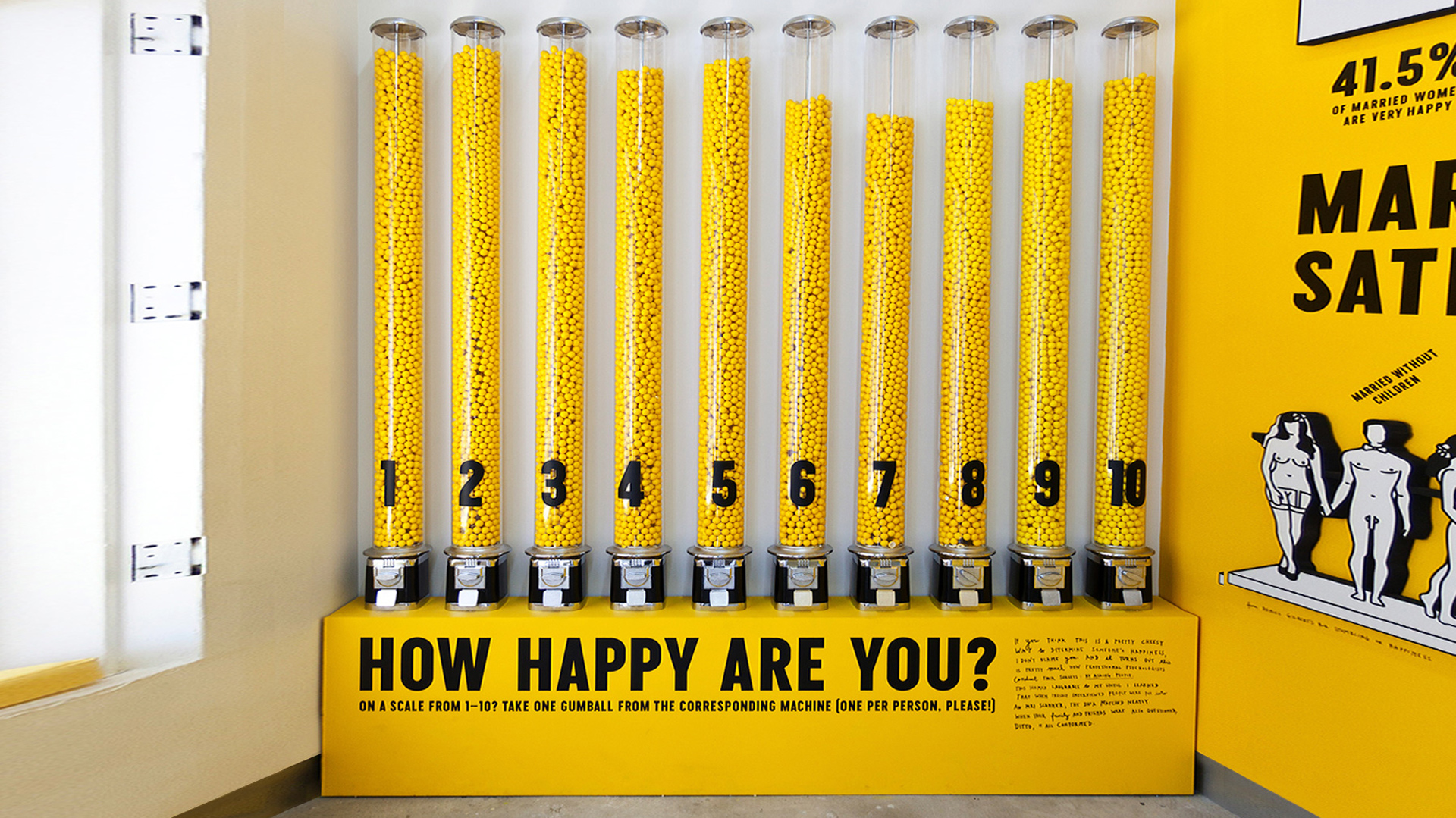

Happy Show, Stefan Sagmeister’s exhibition based on the movie. Photo: sagmeisterwalsh.com

Photographs by Valentin Bo (unless specified otherwise).