Ten Iconic War Photos of Anastasia Taylor-Lind

Anastasia Taylor-Lind is an English photographer and poet, who works in the documentary genre. She covers the war in Ukraine since it started in 2014.

Together with Alisa Sopova, who writes for The New York Times, they have been working on a project called 5 Kilometers from the Frontline, which they started in 2018. Back then, Alisa held interviews with people from the Donetsk region — she studied anthropology at Princeton and knew how they should be done — and Anastasia followed her with a camera. They posted photos and stories on Instagram accompanied by a #5KFromTheFrontline hashtag. Soon after, international media outlets got interested in their work. The project has been gaining pace since then — it is currently exhibited in the Imperial War Museum in London. Anastasia told Bird in Flight about ten images from the frontline cities of Ukraine.

The barbecue

In the summer of 2018, we came to Avdiivka, Donetsk region, and rented an apartment there. Then we went on foot around the neighborhood, looking for our story’s to-be protagonists. One of the locals said that there was a family nearby who had a horse. And I love horses! So I thought we should go there and say hi. That’s how we met the Grinik family, whose story we’ve been covering this whole time.

On the left here is Mykola. He used to work in the cold coke factory in Avdiivka, which was the main place of work for many residents. The factory kept operating through the heavy shelling in 2014-2015 but was closed soon after the beginning of the full-scale invasion. That’s when Kolya volunteered for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He’s still in the army, but he doesn’t want to disclose his exact whereabouts.

Next to him is his wife Olga. She was a housewife and took care of their two children, Myroslava and Kyrylo. In February, Kolya managed to take them out of Avdiivka and drove them to Poltava, where they stay to this day. But in this photo, which was taken in 2019, they still have no idea of what is coming. Here, their extended family gathered for a picnic. Together with them, there is Viktoriya, Olya’s sister, Viktoriya’s boyfriend, and his daughter from the previous marriage. It’s not their regular picnicking spot. They used to go to the forest that was very close to their home. But since the war started in 2014, that area became contaminated with landmines, so it’s dangerous to go there. Luckily, Vika’s boyfriend owns a car and they can drive to this lake. They like this spot — children and adults go swimming and picking mushrooms in another, safer forest.

Soldiers

This picture shows members of the AFU digging trenches and reinforcing them with logs. As far as I understood, these were called artillery trenches: they were deep and well-fortified for having artillery positions in there. This photo was taken in 2022 in Sloviansk. At that time, the Russians were still occupying Sviatogirsk, Lyman, and Izyum, so the frontline was closer to Sloviansk than it is today. Soldiers were taking shifts to build new combat lines.

When documenting their work, Alisa spotted a heart-breaking thing. She was born in the Donetsk region and spent many years there. Just like everyone who lived in the area, she was familiar with the visual experience of driving, when every road — icy in the winter or dusty in the summer — is lined with poplars on both sides. Now poplars are chopped down to become fortifications. This is how the war changes the Ukrainian landscape: what once was alive and recognizable has become dead, damaged, and hostile.

The focus of our project has never been on the military. Of course, we wanted to acknowledge their presence, but we mostly tried to show ordinary lives disturbed by the war. We tried to tell stories about these people without reducing them to cliche characters. During the war, people are rarely seen as friends or parents, engineers or artists — instead they become civilians or military, refugees or internally displaced people, separatists or collaborators. They become collateral damage. So we wanted to represent the people in the pictures in a way that they will recognize themselves and their lives beyond war.

The destroyed building

This photo was taken in Lyman, in 2022. I went there to document the consequences of the Russian aggression and to talk to the people who survived the occupation. This is not my typical photo. Our project is built around genuine friendships and warm relationships. I like meeting people, visiting their homes, sitting in their kitchens, and chatting about dates, jobs and life in general, while kids are running around. This image is not like that. I wanted to show the damaged city, but a single picture doesn’t really convey the level of destruction in Lyman

You can also see a cliche here, a man on a bicycle. Alisa and I gave a series of lectures in American universities back in 2016-2017, which we called “Looking for Lada’s in Ukraine”. We were talking about cliches in documentary photography and how foreign journalists come to Donbas and always try to take a picture of a Lada. You won’t find a Lada in my photos, but other cliches might pop up from time to time. You have probably seen some of these images, which are used to show the horrors of the war. Apart from men on bicycles, there are also women discovering their loved ones dead on the floor, women with their hands on coffins, children playing in ruins, refugees with all of their bags, and so on. There are so many similar images that they eventually become cliches. It doesn’t mean they have no truth in them. They do, but some photographers can take candid pictures of them, and others just turn them into another stereotype.

The baby

This is 2019. Kyrylo Grinik plays on his mom’s phone in their house in Avdiivka. Both Kyrylo and his sister Myroslava were born after the war started, so neither of them has ever known what peace is really like. Most of my time with Grinik’s was spent with the kids. They taught me some Russian words, and I taught them a bit of English. We got along really well. They were happy to show me their toys and their yard, and for me, as a photographer, it was delightful to have such willing guides.

Now Kyrylo and his family live in Poltava, he’s about to go to school. When I saw Grinik’s in December, Kolya called Olya to tell her that their house in Avdiivka had been destroyed. So this room in the photo doesn’t exist anymore.

Olya and Vika have relatives in Poltava. Initially, they lived all together — three families in one house. Kyrylo and Myroslava spent time with their cousins of their age. Then Olya managed to get a house of her own. Last summer, with the help of the extended family, she renovated one room, where she and the kids sleep. There is no running water in the house, and Olya can’t find a job, so continuing the renovation might be problematic. But they have some ducks in the yard, and the kids can go to school offline. That’s already good enough since so many children in Ukraine don’t have even such basic opportunities.

The election

This is Mariinka, a small town in the Donetsk region, which is now almost completely destroyed. In 2019, the frontline sided the end of the town and part of the buildings were damaged. Residents were trying to get compensation from the Ukrainian authorities and NGOs to replace windows and repair roofs. People, who were staying in Mariinka since 2014, have long stopped believing in positive changes, but they still went to the polling stations. During the presidential election, most of them voted for Zelensky. But in the parliamentary election, which is shown in the picture, they voted for former Yanukovich elites.

The diner

Most of the families that we’ve been following since 2018 have left their homes now. But some of them stayed. When I asked them why they stayed, they gave me a variety of reasons. They often said that they have relatives who refuse to flee and they can’t leave them behind.

This is Tetiana and her 90-year-old mother-in-law Lera. They are from Opytne, which is a very small village in the gray zone between Avdiivka and Donetsk. When the war started in 2014, Tetiana and Lera moved from Opytne to Avdiivka, and Tania’s husband, Sashko, stayed in Opytne. He lived in the basement of their old house, which was completely destroyed. The house in Avdiivka was also shelled, but they managed to repair it. Sashko doesn’t want to leave Opytne, and Tetiana stays in Avdiivka to take care of Lera. Their family was separated along gender lines as is very common these days.

We visited Tania and Lera for lunch in 2019. I like to photograph people I know and with whom I’ve spent a lot of time. Of course, sometimes that can’t be the case. In September, I spent three weeks in Kharkiv and mostly photographed the aftermath of Russian missile strikes. I didn’t have a chance to talk to every firefighter and every rescuer. Doing this kind of here-and-now documentary photography is essential, but I don’t have very much heart for it. Instead, I always lean towards gentler representation.

The cross

The woman’s name is Anna. This is the grave of her son who was killed in their home the year before. He found an unexploded hand grenade. He opened it and it killed him. This graveyard has been inaccessible to the relatives of people who were buried there for some time. Ukrainian military positions were around, there was active shelling, and there was also a big risk of unexploded landmines. But in 2019 the graveyard was finally opened for visitors. A pair of local activists, Olena and Rodion, drove their neighbors to the cemetery. That’s how Anna got a chance to visit her son’s grave.

Thinking about these things is devastating. But I’m trying to keep perspective on that suffering and pain when I’m working. Besides, I always have a choice. I can go home — I still have one — I can stay in London and never come back to the active warzone. These people have no choice. The same is true for Ukrainian photographers. They keep documenting history while taking care of their houses, evacuating their families, saving their dogs. Being a storyteller, I thought I had a good imagination, but I can’t imagine how are they coping with this.

The back

This is Olena, whom I’ve mentioned before. Lena and Rodion stayed in Opytne for all these eight years and took care of their elderly neighbors. The whole village lived with intermittent electricity and water, so Olena and Rodion campaigned to get at least electricity reinstated.

On June 8, 2022, Olena stood in her backyard when she heard an incoming shell. She turned around and ran to the house. At that moment one piece of shrapnel hit her in the back, almost severing her spinal cord, and the second one hit her right buttock. It was very hard to get a heavily injured person out of Opytne last year, but they succeeded.

This picture was taken in Pokrovsk. Olena had surgery and she had to visit the hospital regularly to have her wound bandage changed. She is now all right. I asked Olena and Rodion: “You are not going back to Opytne, are you?”. They said: “No, of course, not, this is too dangerous. We are just going to drive back to Opytne every weekend and do the chores, attend to the garden, and make sure everyone’s okay”. And they kept going back until Opytne was taken by Russian forces. They live in Kryvyi Rih now.

The farewell

This is Kurakhove, 2019. That’s when checkpoints were still open. Kurakhove is a small town, but there was a lot of movement there. People came there to withdraw money from the Ukrainian ATMs. It was also the place from where buses would go to the occupied territories. There were families and communities who were divided by the frontline. People said their goodbyes here before going to the occupied territory and never knowing if they will see each other again.

I like this image. It looks like street photography. You can see a strong emotion here — look at the way the man’s head is buried in her shoulder. It’s also an example of a compromise, which we often made when working on this project together with Alisa. Sometimes I took a picture, which seemed beautiful to me, and Alisa struggled to find the right words to write beneath. Sometimes Alisa wanted to write about something that mattered to her and I couldn’t think of a visual to illustrate her thoughts. Like in this case. She wanted to write a story about millions of people who are forced to move through checkpoints every year. And I was so lost for visual representation because you can’t take pictures at checkpoints. And then I saw this scene and thought — this is it.

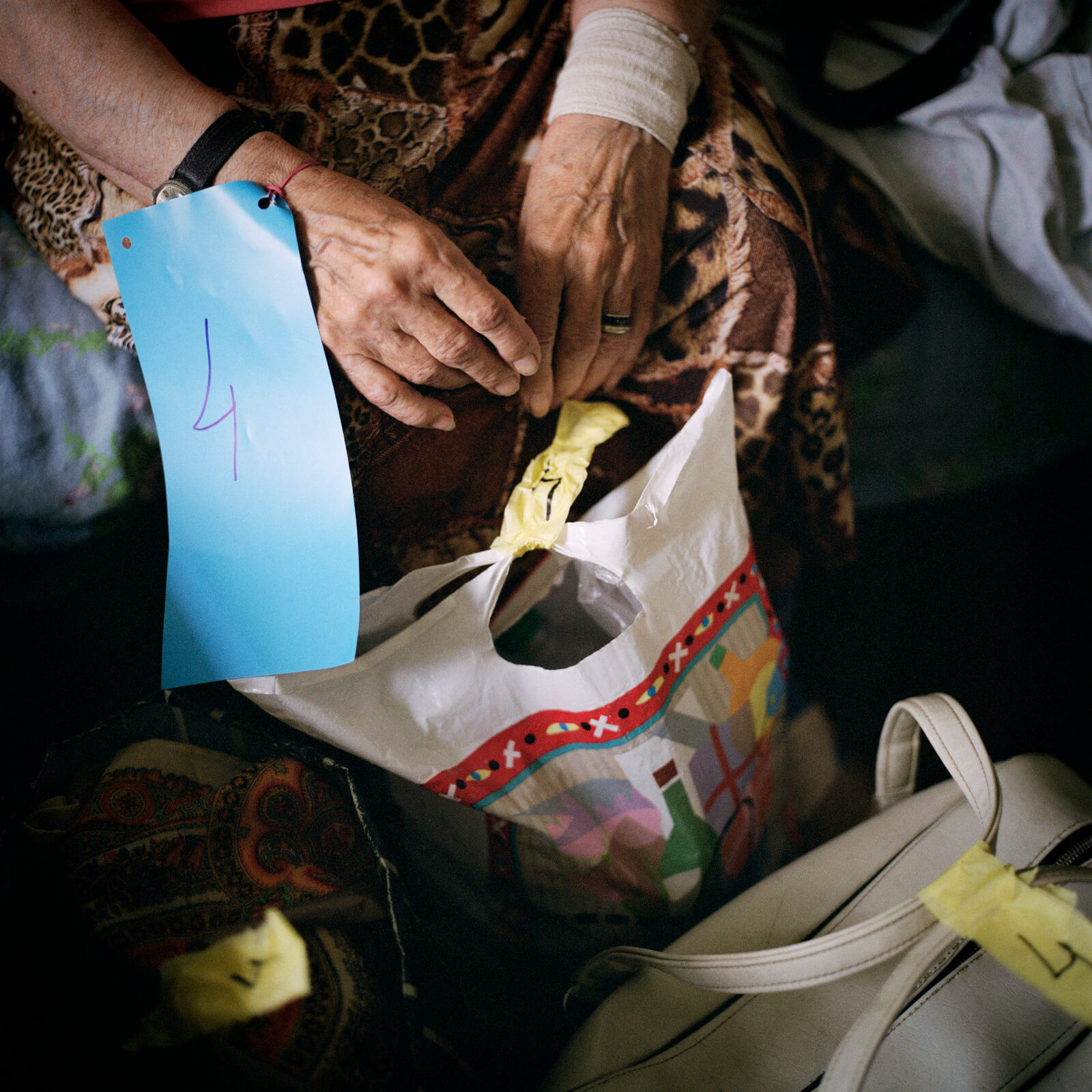

The numbers

This photo shows an elderly woman, who’s being evacuated from Sloviansk by the Ukrainian Red Cross. She was transported first by ambulance and then by train. In order that patients would be able to be re-united with their luggage, they were given these numbers.

A lot of people have left their towns in the Donetsk region. Of course, some of them stay, but the majority of our protagonists, who we’ve been following since 2018, are now living somewhere else. I would like to keep documenting their lives further, but I also want to continue telling the story of this region. That is why we are looking for new heroes, for those who stay. For instance, during my visit to Lyman, I met a truly inspiring couple called Volodia and Nadia. I guess they could be our next protagonists.

New and best