Stay Where There Are Songs: How Thousands of Roma People Survive in Transcarpathia

Beyond the Poverty Line

From the first steps the photographer and I are surrounded by a crowd. They are asking to give them money or clothes, or help get someone out of prison… People think that we are NGO representatives, as they’ve have already gotten used to their visits. The Roma try to make use of everything. There is a building for the Reformed Church in the middle of the camp, but they go there not because they are religious, but because the church distributes humanitarian aid from Europe. About one third of children from the camp go to the local primary and middle school (there are 790 school-aged children registered with social services, but not more than 250 of them attend the school; also, many girls quit because of early pregnancy), but not because they are hungry for knowledge, but simply because they are hungry, and the school provided free breakfasts from the Maltese Aid Service.

Kalman Sabov, a son of a Roma baron, has an important responsibility: collect the fees for electricity and water from the inhabitants of the camp. The amount is very small compared to the prices in the capital: 50-100 UAH ($2-4) — it doesn’t take too much electricity for one or two light bulbs, and the people in the camp don’t have separate yards — but the Roma poor are almost crying when they have to part with it.

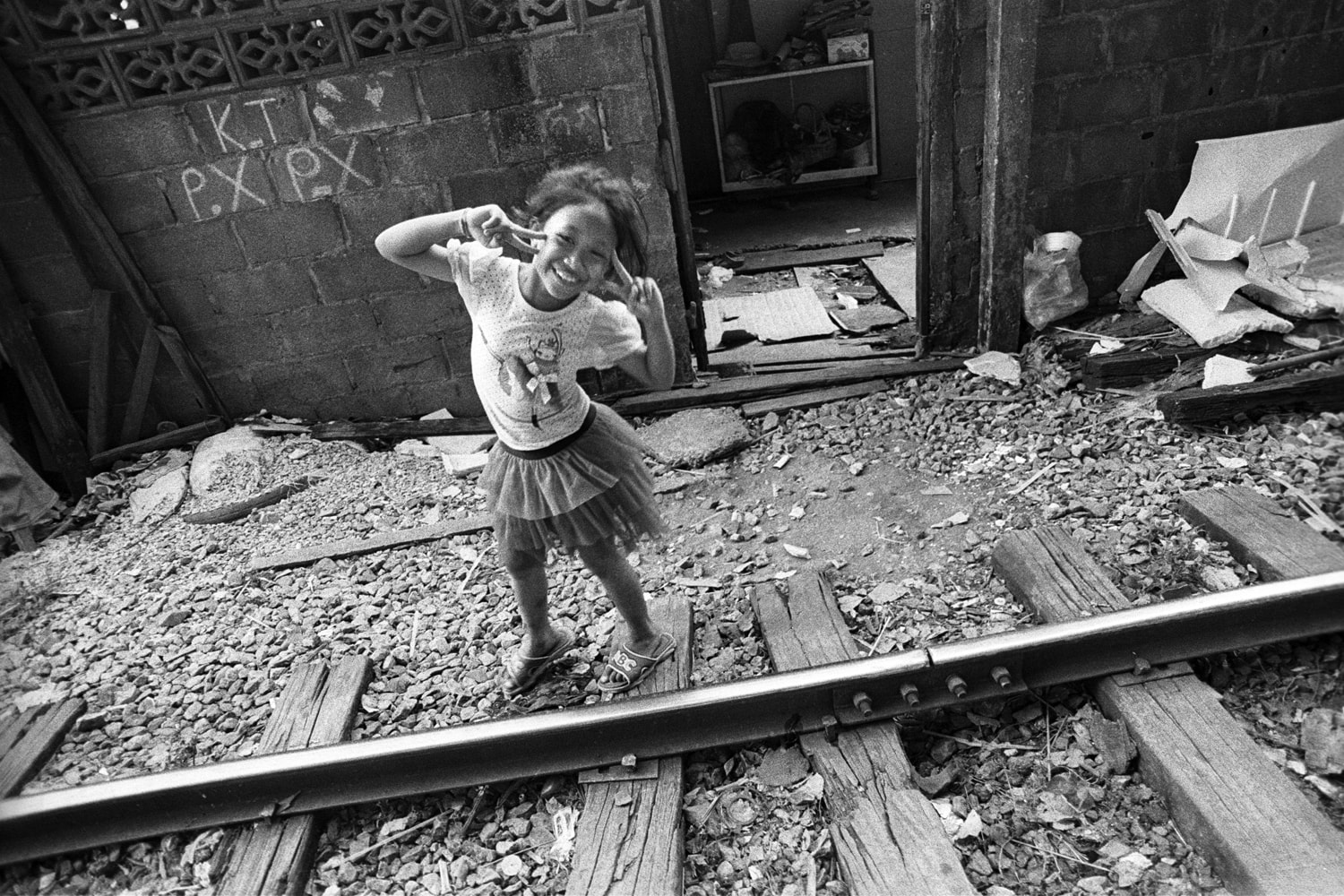

The inhabitants of the Okremnyi camp are not ashamed of their poverty. On the contrary, they show it off. Everyone tries to drag you into their house to show you how poor it is — what if you could help? Some houses look like corrals — made hastily out of everything at hand, with cellophane instead of glass in the windows, with cracks in the walls. It is unclear how people survive the winter in these buildings. But they do: they dress warmer and turn up the heat in their stoves.

There is a caste system in the camp, there are rich and poor neighborhoods. You can see people who literally live in the huts here, sometimes in a clay hut a carpet replaces a door, there are almost no houses with glass windows. The stratification happens even in everyday life: the rich treat the poor with disdain, marriages are made between families with similar levels of income.

Communication with the Outside World

Traditionally, the Roma communicated with the local authorities only through intermediaries; that is, the infamous Roma barons. Now there are NGOs in the camp that are trying to teach the people direct communication with the authorities.

“In the recent fifteen years the influence of the barons on the life of the community has decreased, — Myroslav Horvat, the host of Romano Jivipen, the only Roma TV show on the Transcarpathia state television, says. — The barons used to be indispensable, for instance, when applying for benefits or a pension — Roma would go to the baron as they were illiterate and helpless when it came to legal matters. Now it is easier for them to go to the NGO professionals.” Another job of the barons — to solve the disputes inside the camp — is also almost no longer necessary. More and more often the sides of the conflict would go to court. Human rights organizations help the Roma in courts and with paperwork. They are also in permanent contact with the Ombudsperson, an advocate in front of the local governments for providing jobs to the Roma. All of these steps are aimed at integrating the Roma into society. The barons can see for themselves that they start having less power, so more and more often they would leave the communities and start businesses. The only aspect that they still fully control is the relationship between the inhabitants of the camp and law enforcement.

“Police can enter the camp only when accompanied by the barons, and in a way barons even take part in questioning and the preliminary investigation.”

It happens that the border between the old and the new lies between generations. For instance, Kalman Sabov, a son of a Roma baron, is the deputy head of the The Future of the Roma of Berehovo NGO.

The Future of the Roma of Berehovo is chaired by Istvan Papp, a councillor on the city council, an official representative of the Roma in front of the city authorities. The organization solves a variety of tasks. It helps find employment (“We have accomplished the fact that all the street sweepers in Berehovo are exclusively from the camp”, — Papp proudly says), provides medical services, primarily the obligatory vaccination of children, controls the distribution of social benefits — so that no government aid went to phantom names. The Center maintains the minimum sanitary conditions at the camp, to the most possible extent, and distributes humanitarian aid that comes mainly from religious organizations.

The Future has won several grants from the Renaissance Foundation and the European Union TACIS program, mainly for the passportization of the inhabitants of the camp.

“The lack of documents is one of the key issues at the camp, — Kalman Sabov says. — Many people don’t have any documents at all, and they have to go to court to get a passport.” The lawyer’s services cost 3,000 UAH ($120), another 1,000 UAH ($40) needs to be paid to the Immigration Service. For many people here this is an absolutely impossible amount of money. A regular camp inhabitant thinks that a salary of 1,000 UAH is good. The main income sources for the Roma are single mom benefits (marriages are not registered officially, so all mothers here are technically single — Ed.) and the money earned by sorting garbage at the local dump.

The more modern the Ukrainian system of accounting, including tax accounting, becomes, the more left out the Roma are.

You can’t get a tax ID without a passport , and you can’t get a job without a tax ID. People who have no documents can’t be admitted to the hospital, which results in epidemics of TB and other infections.

Formally, Berehovo camp has a legal status. It looks like the money from the NGOs and Ombudsperson visits have had their effect. To apply for a passport, people from the camp don’t need to submit a certificate from the housing office or a document from a bureau for technical inventory. In any case, the local Roma don’t have any property rights for the huts they live in. The testimony of two neighbors is enough for a Roma to get a passport, where the Okremyi camp neighborhood is stated as his place of residence — no street name or house number. Moreover, these clay huts can’t really be called houses, and streets there are also a relative notion. There is nothing but potholes in the mud, crossed by carts and very rarely by old Soviet cars. There is electricity, but the water comes from standpipes.

The showers are in the building of the cultural center. There are only 9 cubicles for the whole camp. The only toilet in the camp that is connected to the sewage system but doesn’t work is also there, as well as the clinic with no visitors.

People don’t trust vaccinations here, and doctors in general. They prefer traditional healers.

It is said that the Roma came to Berehovo from Hungary in the 1930s, when according to the First Vienna Arbitration, Berehovo was transferred from Czechoslovakia to Hungary. In January 1946, this town became a part of the Transcarpathian region of the Ukrainian SSR. The border, which lay literally outside the city limits of Berehovo, tied the Roma to Ukrainian land. Only the Hungarian language is a reminder of the past — almost everyone in the camp speaks it, but not the Roma language. Without the Roma language, traditions, folklore, romances die — they are preserved only with the effort of several enthusiasts, like Aladar Adam, the director of the Romani Yag theater in Uzhgorod. People in Berehovo will most likely not understand Roma television that is broadcasted from Uzhgorod, and the same is true for newspapers and textbooks for the Roma that are printed in Kyiv at the state’s expense. The Hungarian language is turning the Okremnyi camp into a ghetto geographically and culturally.

The Unadjusted

History has performed an evil experiment on the Roma, and after WWII has deprived them of the social niche that they have occupied for many generations. If we refer to literature and folklore, we’ll see that the Roma have not always been such pariahs. In the songs and legends the Roma are depicted as tricksters, but they are not marginalized. A Roma of the past always has a job — as a jeweller, a groom, a blacksmith, or even a mailman. All of this collapsed with the transfer to a sedentary lifestyle, which started in the post-war years and got established when the campaign against nomadic life was started in the Soviet Union. As a result of the campaign, the Roma were tied to the land (something similar happened to the minorities of the North), which led to an entire people losing the old skills and not acquiring new ones. Nobody keeps farm animals in the Okremnyi camp or works on the land. And it’s not because people here are exceptionally lazy, but because they simply don’t know how to do it. The skills for working on the land are acquired over generations, you can’t introduce them by force.

The local military commissar has given up on the Roma long ago — they don’t get called up for military service. Kalman Sabov thinks that the issue is a mutual lack of trust. The Roma don’t believe that the state will fulfill its promises, and the state doesn’t believe that the Roma will go to the frontline to fight. There are, of course, exceptions: there are several Roma who are currently in the ATO zone (a term often used by the media and government of Ukraine to identify the territory where the war in Donbass takes place - Ed.), and the abovementioned Aladar Adam has recently published a book about the Roma Resistance. He complains that in Europe they don’t pay enough attention to the genocide of the Roma population. For instance, the International Roma Genocide Remembrance Day (to mark the extermination of all Roma in Auschwitz in August 1944) is official only in Poland and Ukraine.

The Roma representatives were not even invited to the events dedicated to the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in Kyiv, where the authorities couldn’t agree on a monument to those Roma who perished in Babi Yar.

At the same time, in Ukraine alone, 20,000 Roma were killed during the war, and this is a significant percentage of the Roma population. According to the first post-war census in 1959, there were 30,000 of them in the Ukrainian SSR.

The main document that defines the policy of Ukraine towards the Roma is the Development Strategy for the Roma Minority up to 2020, which was signed already by President Viktor Yanukovych. The local authorities in Transcarpathia regularly report to Kyiv on the implementation of the Strategy, which of course has no real effect on the people at the Okremnyi camp. However, the problem of such territories is more global than it may seem. Favelas threaten the well-being even of developed states (let’s remember the terror attacks in Brussels that were perpetrated by people who live in depressed areas that dropped out of sight of the Belgian authorities). Adapting such camps to a normal life may be the hardest task facing humankind in this century.

New and best