Thousands of Kharkiv Residents Spent Three Months in the City Metro, Photographer Pavlo Dorogoy among Them. He Recounts how People Found a New Home Underground

Photographer Pavlo Dorogoy photographed the Kharkiv metro from the 4th of March until the 24th of May, when underground public transit was re-launched. He visited almost all stations during that time but spent the most time in the Armiyska station — over ten days. His father lived there for three months. Pavlo made a short documentary that won an award at the Docudays UA festival’s Civil Pitch 2.0 programme. In end-May, the people in the metro were asked to pack up and leave the stations. For some, it was emotionally difficult.

Photographer and director, he studied documentary photography and photojournalism at the Docdocdoc School of Contemporary Photography in St. Petersburg.

— I made friends with some people in the Armiyska metro station, with whom I stay in touch to this day. I remember there were only narrow paths between the people during the first days: you could only sit there because there was not enough space to lie down. I believe about 1,500 people lived in the Armiyska station at the time, and only a third of them remained by mid-March.

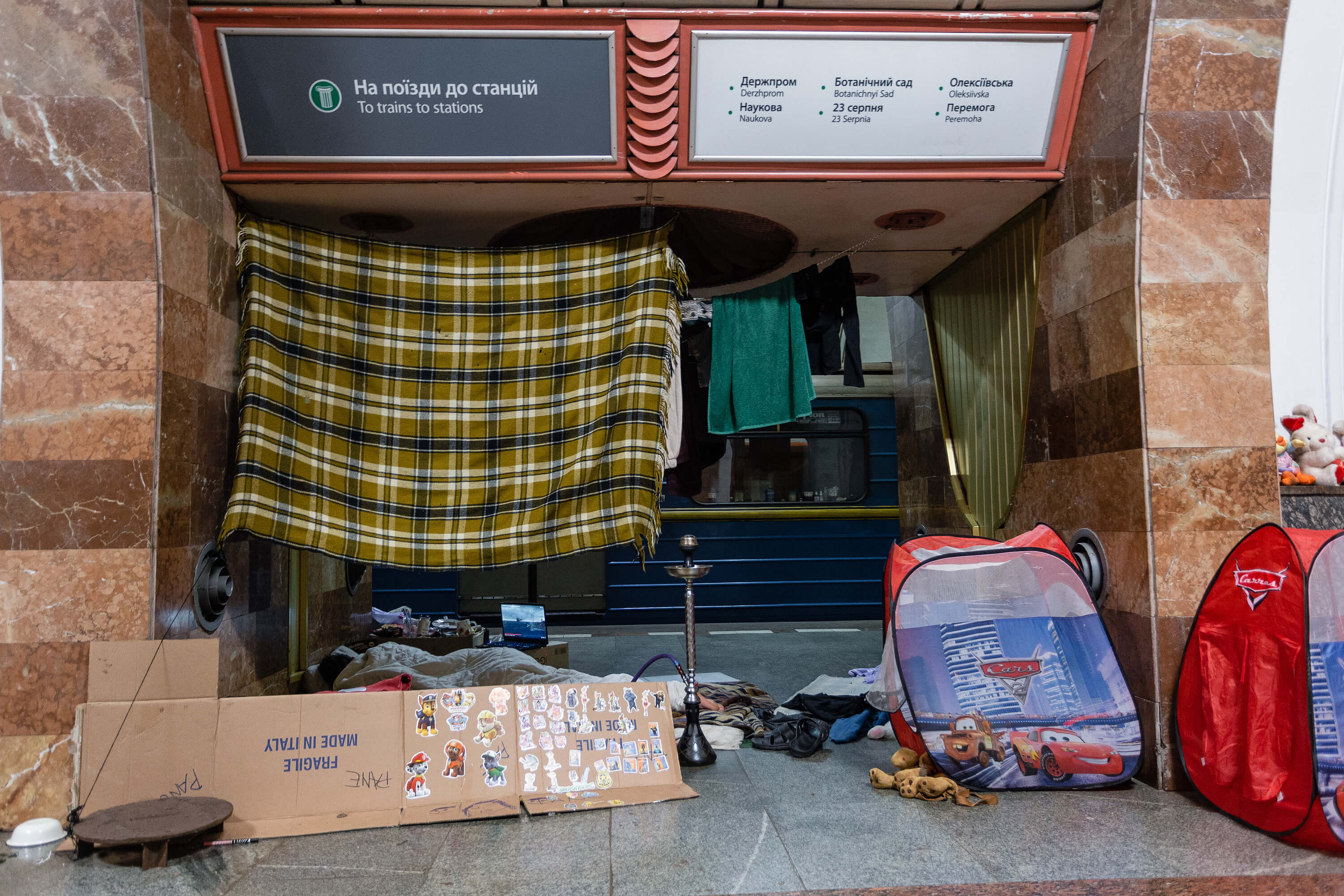

People spent the nights both on the platform and inside the carriages, with the latter considered a more comfortable option. Families with children were accommodated in utility rooms because they were warmer and allowed some privacy. The metro opened at 6 AM and closed at 6 PM and later at 9 PM.

A few dozen activists immediately took on organizational responsibilities. Local authorities provided only dry rations, bread, and a little dairy. Meanwhile, volunteers prepared three hot meals a day, paying from their own pockets for the food. There was no panic because everyone felt safe in the metro. Still, people read the news together, cried, and shared whatever information came from the surface. Teachers came to hold classes for children.

When I first entered the metro, the first thing that struck me was how pale everyone looked for the lack of sunlight. Also, people were always sleepy because of insufficient ventilation.

The first thing that struck me was how pale everyone looked for the lack of sunlight.

People couldn’t shower underground, so many had to go home for that. Sure, you could heat up some water and use a washbowl, but you would have to do it in the toilet. Bear in mind that only old stations have larger public restrooms, which can be used by up to five people, and those in the new stations are just tiny. There was no running water on some days, and the stench was unbearable.

People quickly started setting up their temporary living spaces. I think I saw a floor lamp in the Beketova station. To others, people brought rugs, beds, and even TVs. Some took their pets with them. Dogs were barking, and cats sometimes roamed the tunnels, albeit causing little trouble.

There is that computer game, Metro 2033. It is based on Dmitri Glukhovsky’s eponymous novel set in the world where people live underground, breeding animals and growing gardens there. A world like that felt very much possible during those three months.

People were allowed to walk in the tunnels until mid-March, and then you could go only with a metro staff member. It took me about two hours to get from Istorychnyi Muzei to Akademika Pavlova on foot — there are five stations between them. There were no rats in the tunnels, though, only silence and cool air. You could tell how close to the surface you were by the temperature — the warmer it was, the closer.

People were reluctant to leave. One day, PA just turned on, and a voice announced that the metro resumed service. It was perhaps the most emotional day: everybody was angry, sad, and scared. A family with a one-year-old baby lived near me at the time — they had a place to return to, but they were scared to live under shelling.

Kharkiv mayor Ihor Terekhov recommends people return to their flats and says hostel accommodations will be provided to those whose houses were destroyed. Terekhov himself, however, still lives in a bunker, as the rumour goes. Also, a missile hit the area near the 23 Serpnia station recently. People got used to sleeping alone in the dark over those three months. I feel many have PTSD already, although there were no psychologists to diagnose it anyway. It was difficult to leave people with whom you spent nights side by side.

New and best