Paraska Plytka Horytsvit: Ukrainian Vivian Maier

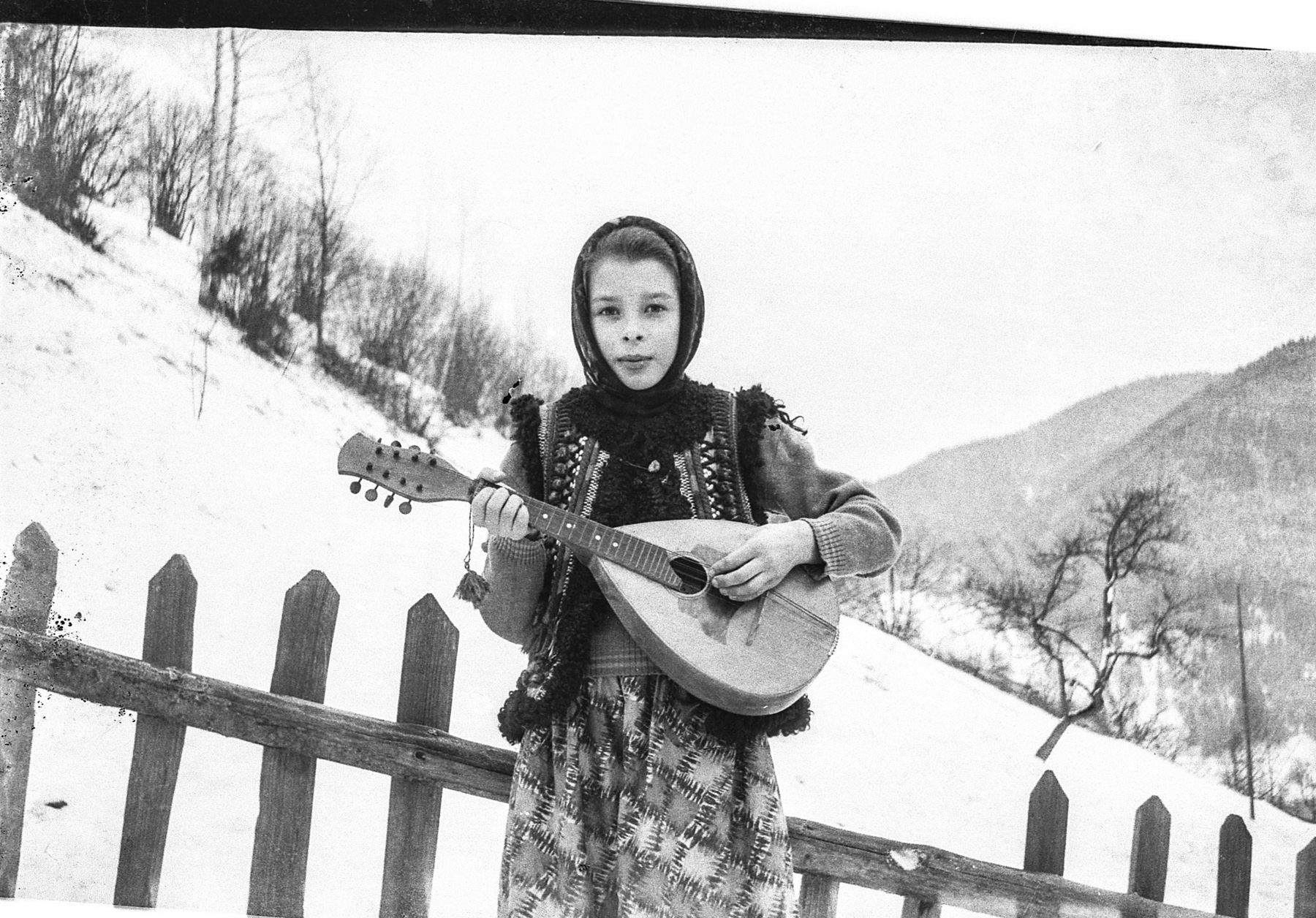

Ukrainian writer, artist and photographer Paraska Plytka Horytsvit became known fairly recently. Her life story and the story of her photographic and artistic archive are indeed fascinating. She is called the Homer of the Hutsul Lands: under the pen name of Horytsvit (Ukrianian for adonis flower) she wrote fairy tales, poems, created handmade books, sculptures, wrote ethnographic notes, created paintings and drawings. Amongst her work there are also religious paintings.

A lot of interest today is concentrated on her photographs. Some of them were exhibited during the Odesa Photo Days festival in 2018, and in 2019 a large exhibition opened in Mystetskyi Arsenal, Kyiv.

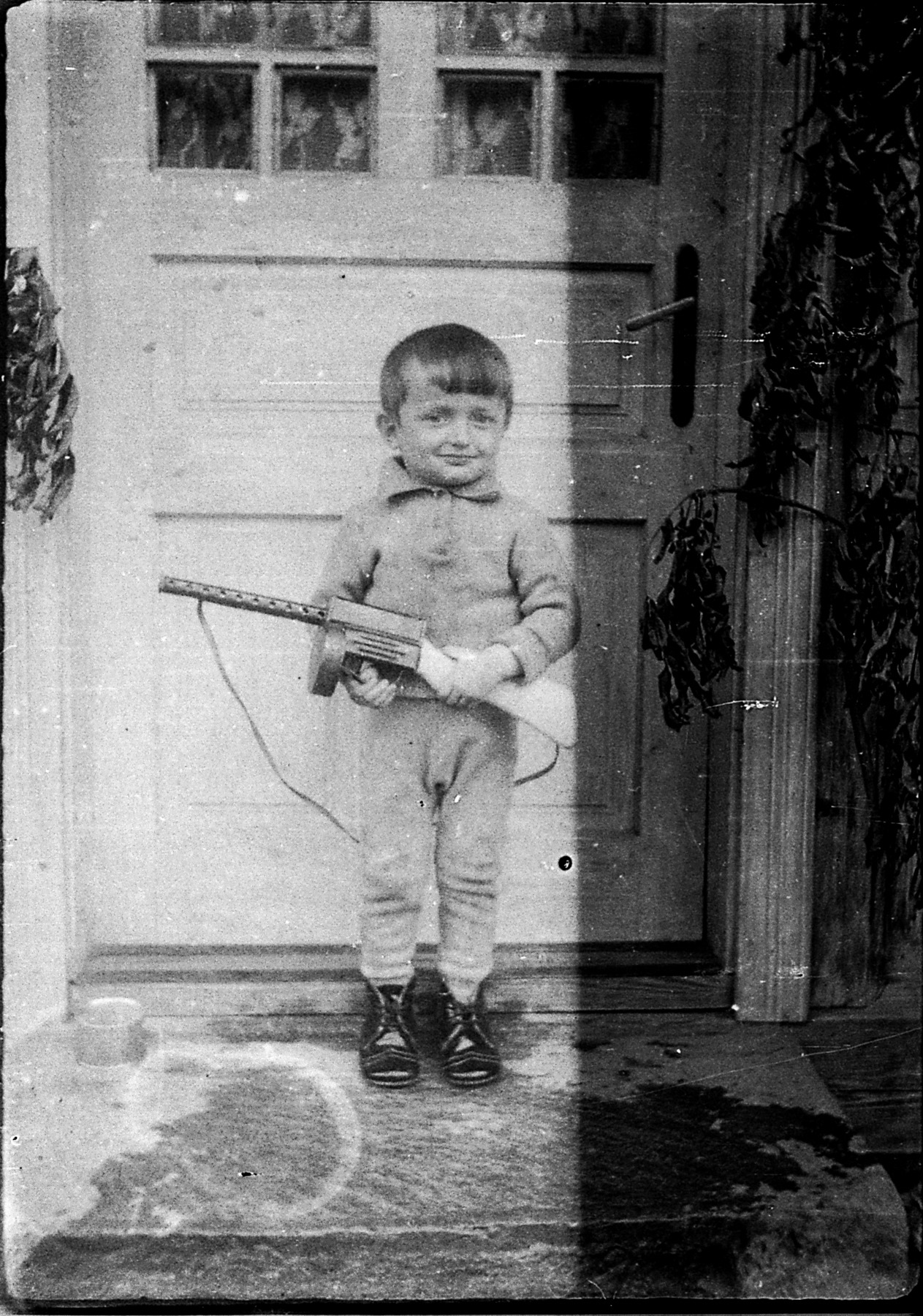

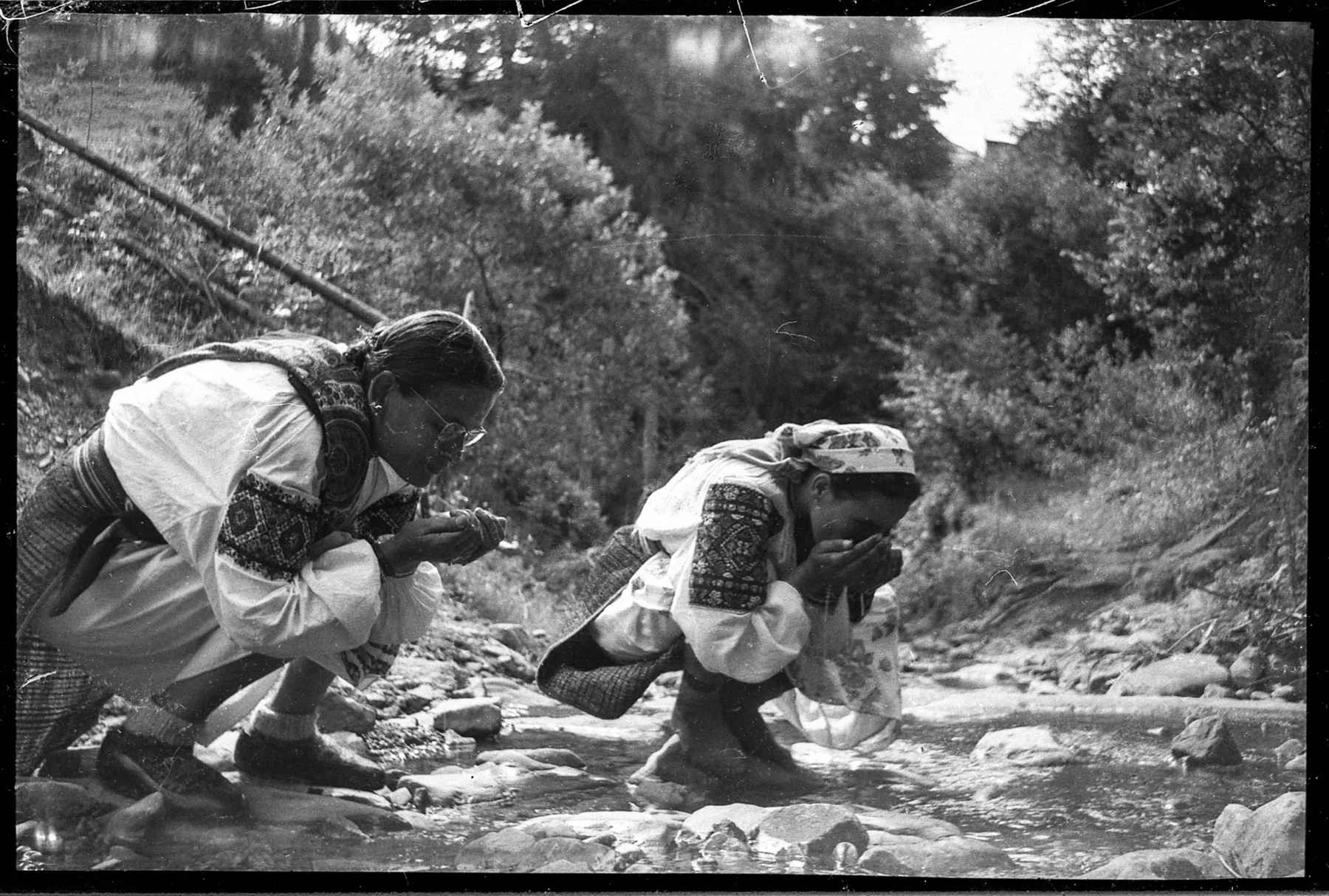

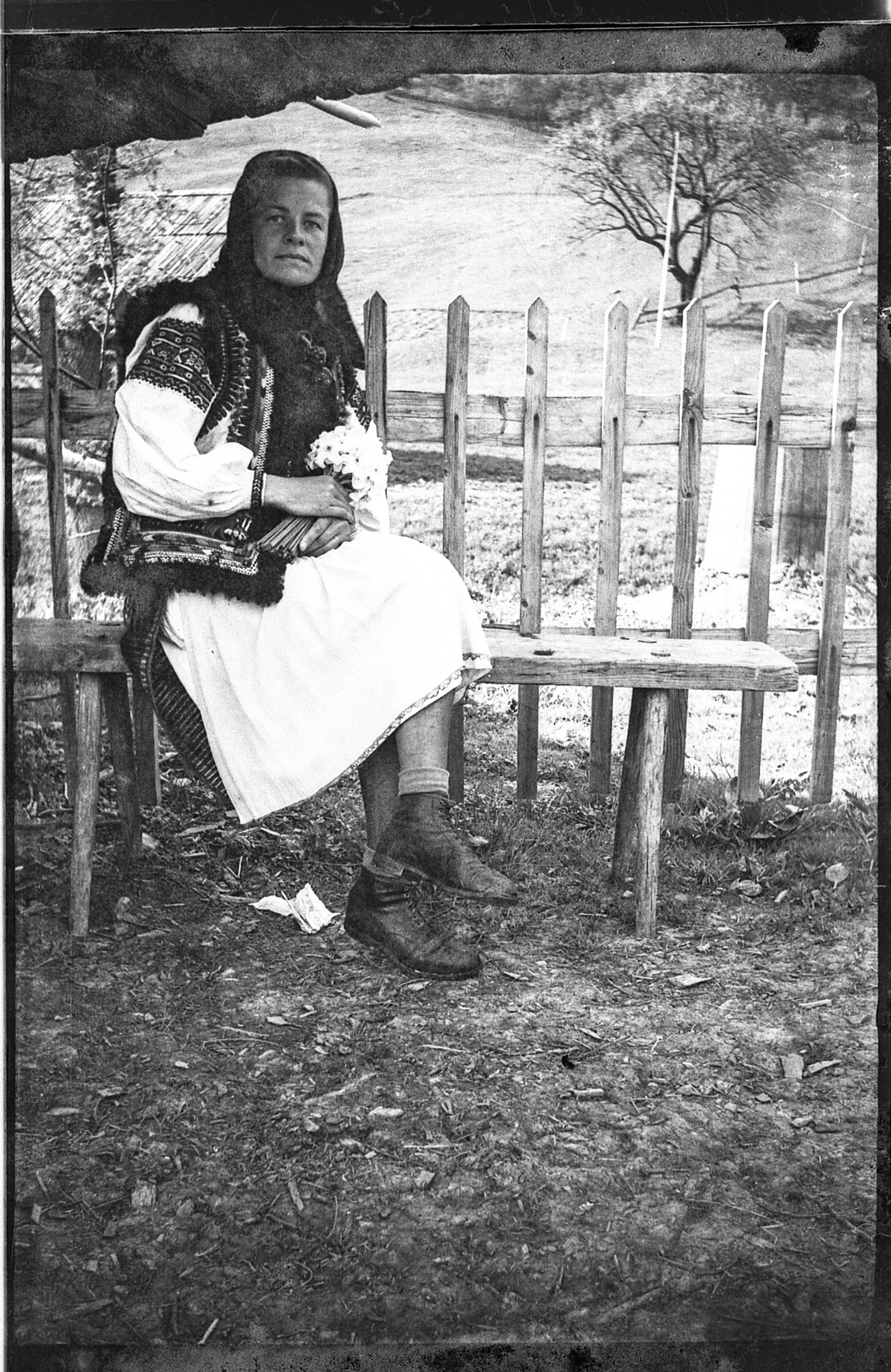

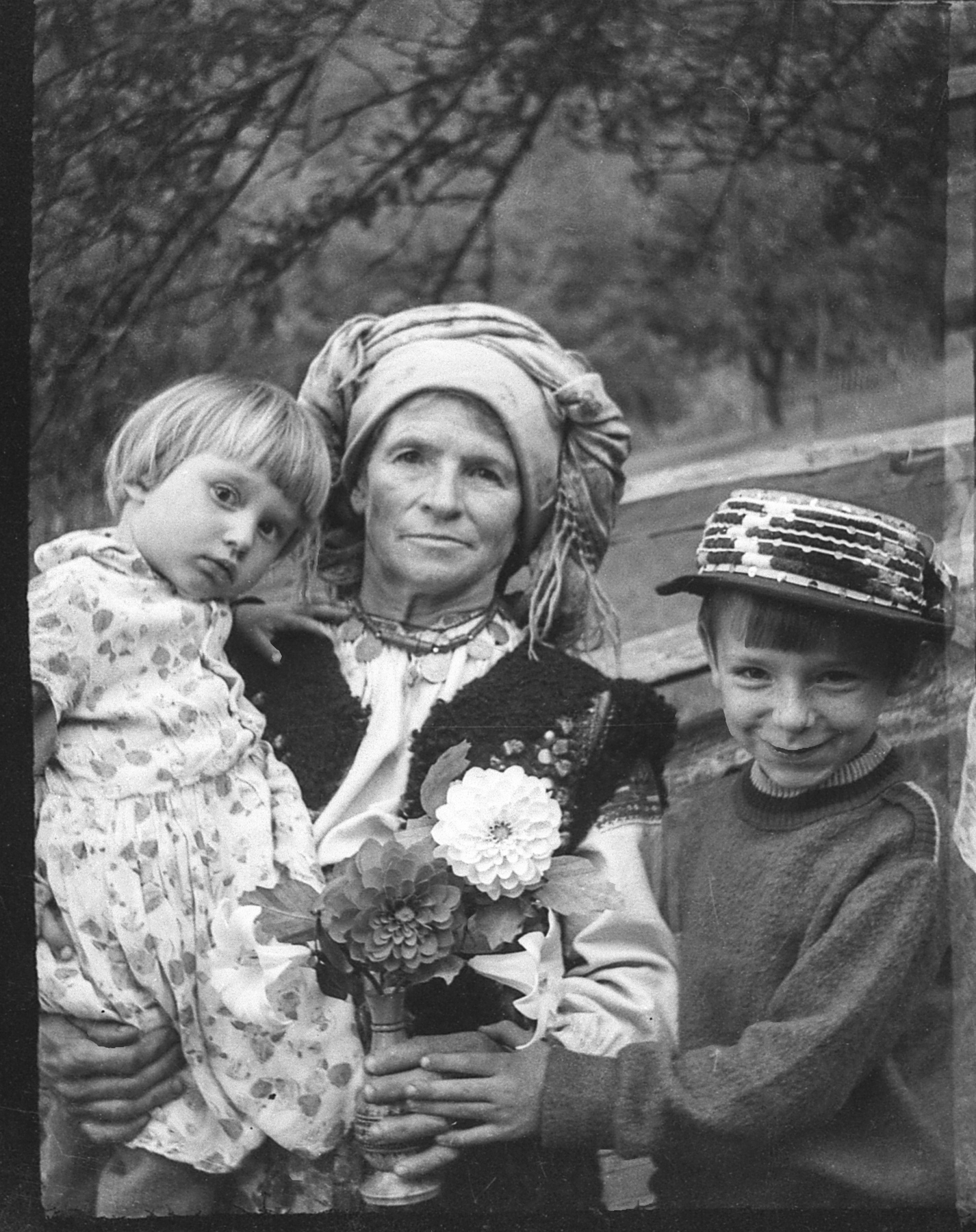

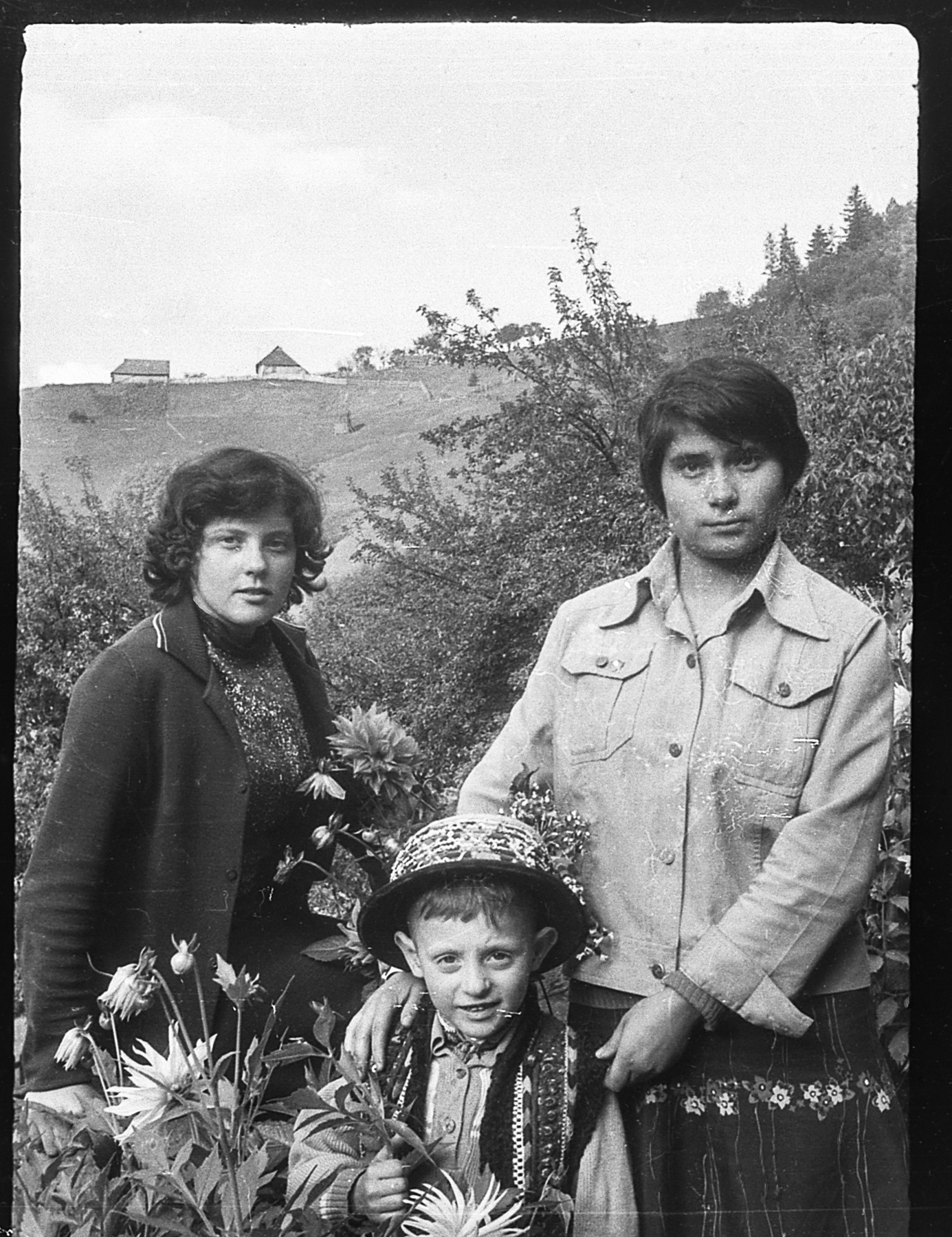

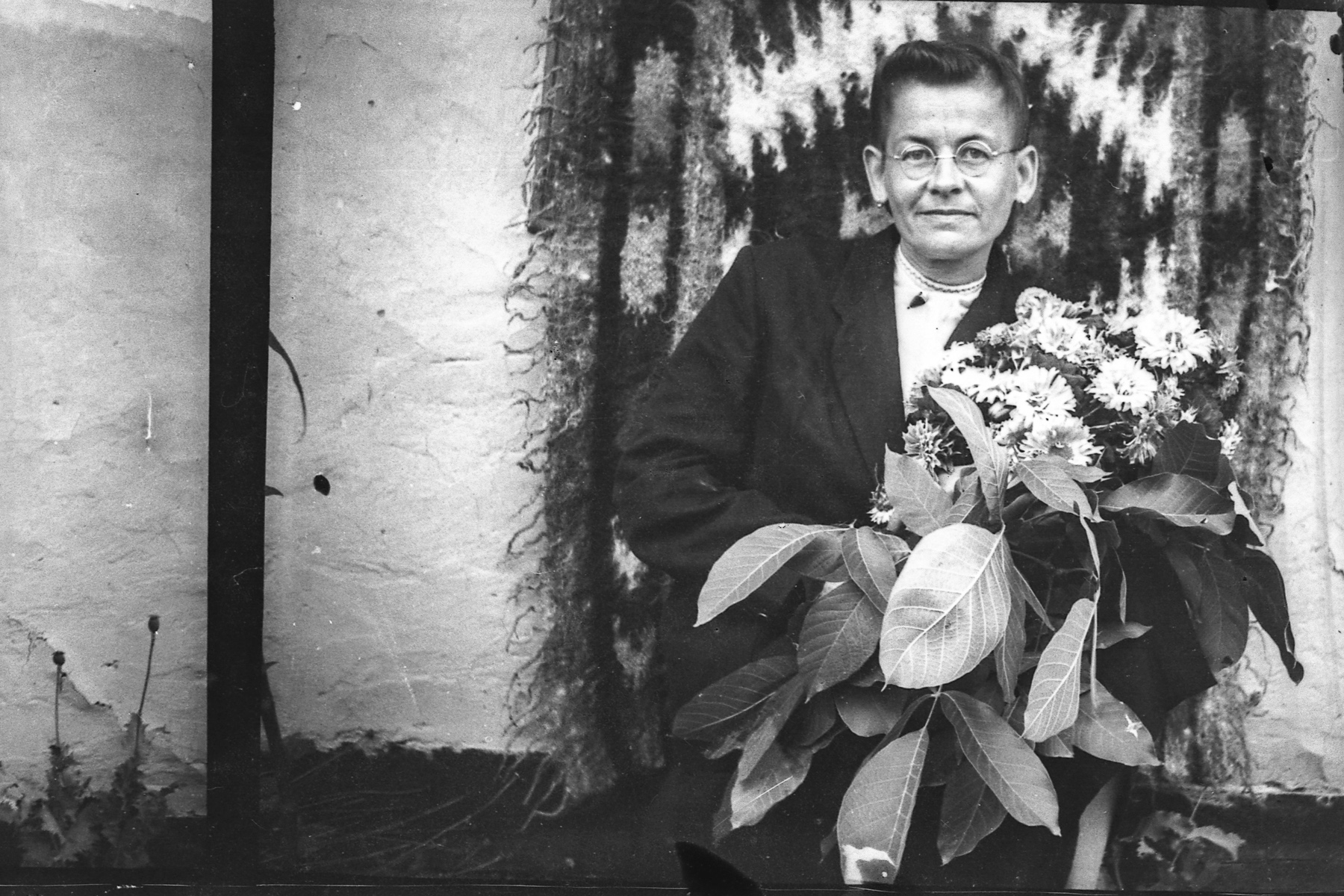

Photographs from Paraska Plytka Horytsvit’s archive

Reality and Fiction

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit came back to Kryvorivnia, a Carpathian village where she was born, after spending 10 years in Stalin’s camps and captured its traditions, customs, people, and nature. In her many photographs, we see an entire Hutsul world, an illustration to decades and epochs. After the author died in 1998, her photo archive was considered lost, but several years ago some of the materials were found.

Her photo archive was considered lost, but several years ago some of the materials were found.

The artist was born in 1927 in the family of a blacksmith, Stefan Plytka, and his wife Hanna, who was an embroideress. It is known that Paraska only went to primary school, but she was homeschooled after. She was a good singer and played various musical instruments (that later she also made by herself), knew some technical things and could speak foreign languages. When the Second World War started, she worked as a translator at the village administration. In 1943, she went to Germany where she worked as a housekeeper for a German family. She then came back to the village where she was born and joined the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. She worked as a messenger under the pseudo ‘Swallow.’

When the Soviet army took over the territory of Western Ukraine, many insurgents were arrested — this happened to Plytka Horytsvit as well. In the winter of 1945, she was sent to Siberia and from there — to a special camp in Kazakhstan.

Despite the fact that Paraska Prytka Horytsvit has become more known recently, her biography is still surrounded by many myths. Researcher Kateryna Radchenko says that they often contradict the archive itself. “One of the myths is that she was a recluse. However, we see from her photographs that she started taking them almost immediately after she came back from the labor camp. She most often took pictures of her family or people from the village. She took part in collective work — in the forest or during harvest. Paraska had many visitors — students, cultural figures, and ethnographers. She exchanged letters with the Sixtiers — writers, artists, and architects from different cities of Ukraine. Judging by all that, we can’t say that she was ascetic, but we could say that she chose her circle herself and communicated selectively. Paraska lived several meters from her parents’ house and has always maintained a warm relationship with her parents and sister, as we can see in her diary and literary entries and photographs.”

The myth about loneliness could appear because she had neither a husband nor children. Sometimes this is explained with a story of eternal love: the young woman allegedly met a Georgian artist in the camp, fell in love with him, but because of the parents’ disapproval they lost touch. When she got out by pardon at the age of 27, Paraska settled alone and never fell in love again. However, this version is just another myth. “There is not a single piece of evidence that this ever happened,” Radchenko explains. “Not a single letter or photograph or poem.”

It could be that many villagers didn’t want to communicate with a former political prisoner — this could make their life difficult and attract the attention of the special services to them. Radchenko clarifies that people had the same attitude to other political prisoners as well: for instance, a close friend of Paraska, Teodosea Plytka Sorokhan, who lived close by and spent her life alone, and had a similar fate.

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit is in a way a Ukrainian Vivian Maier — a self-taught photographer who has the ability to both be in the environment and be estranged from it.

All on Her Own

Paraska Plytka Horytsvit’s archive consists of photographs of smiling people from her village, from babies to the elderly. She gave photographs to people whom she photographed. Plytka Horytsvit documented birthdays and funerals, religious holidays and family events. Everything that surrounded her was in her photographs. As if she was looking for something with her gaze, creating endless pictures with the same plot, one after the other.

Everything that surrounded her was in her photographs.

It is not known how and why Paraska started to take pictures. “It could have been the influence of people from the camp,” Radchenko supposes. “She was surrounded by intelligentsia there, some conversations with those people could have brought the artist to photography. It could be the influence of the region itself: before the war, that area was part of Austria-Hungary and was popular among photographers — there were more photo studios in the Carpathians than in Odesa region. Photographers from Austria and Poland came to the Carpathians; they shot landscapes, folklore, made postcards and developed photoethnography.”

When Paraska Plytka Horytsvit returned home, she got employed at the forestry. She used her first salary to buy a Smena camera, and her second salary for an enlarger. For a long time, she couldn’t develop film and print photographs at her home, because her house was connected to the electrical network only in the 1970s. That’s why she printed her first photographs in the forestry office.

“It was very easy to teach yourself how to do that at the time,” Radchenko notes. “There was a lot of Soviet literature that explained photographic processes. In Paraska Plytka Horytsvit’s library we found several textbooks that explained the technological processes of photography. She learned many things from correspondence. For instance, in letters people explained to her how to develop this or that film. They also sent her film and photographic paper, cutouts from magazines about photography. She got inspiration and information from exchanging letters with friends and from her surroundings, which later impacted her creative work and was implemented in the form of combining Hutsul traditions and new directions.”

Paraska didn’t have a vegetable patch or animals, creative work — letters, books, paintings, drawings, and photography — took up all of her time. In the 1970s she guided expedition trips in the Carpatians. Plytka Horytsvit was interested in politics, she liked philosophy, she was keen on the culture and traditions of India. Her archive included a big album dedicated to space.

Paraska lived in the village, but she still kept up with the newest technologies and tendencies. “In her photographs we see a balanced approach and understanding of how a person should behave in the frame. In the 1960s photographs we see that she used decorated cutouts — it was popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Sometimes she colored photographs — it was also popular at the time. She made masks for the enlarger to emphasize the central object in the frame; created vignette collages; signed negatives with ink, creating a second layer — all these experiments reflect the tendencies that existed between the 1950s and 1970s in the USSR,” Kateryna Radchenko says.

Four Thousand Photographs

When a group of researchers found Paraska Plytka Hortsvit’s photographs, they were very dirty and part of the material was damaged. Because of that, it was impossible to count how many films the artist used and how many she selected. Some are cut into separate frames, in some others frames overlap, and some are almost completely destroyed. Sometimes Plytka Horytsvit sent films to friends in Kyiv with the request to develop and print them in the city.

Today, her photo archive includes over four thousand works. “I think that Paraska’s photographs are beautiful and powerful material for research,” Radchenko says. “Regarding female photographers in Ukraine, we encounter three problems. The first: there were female photographers, but no archives remained available, there are several photographs in private collections at best. The second: creative work of women who photographed in the Western Ukraine, in particular in Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk, now is part of the artistic heritage of Poland. The third: photographs of female photographers who were born and worked in Ukraine but emigrated at some point became part of heritage of Austria, Australia, Great Britain, or France. Unfortunately, when we speak about the entire 20th century, we can count the women who

photographed on one hand. Paraska’s name will be among them, that’s why it is very cool that this archive was discovered.”

The artist’s archive belongs to the community of Kryvorivnia village — it was the history of this village that she captured in people and rituals. These countless images indeed depict entire generations, one after the other. In fact, it is the history of the entire village of the second half of the previous century.

These countless images indeed depict the entire generations, one after the other.

“Speaking about history, we need to understand that there is an official narrative, and there is real history that is not included into the archives,” Radchenko explains. “Paraska’s archive is a testimony of ‘unofficial’ history, which is more truthful. This archive shows the author’s outlook on the region between the 1950s and 1990s. In the photographs we see how the tastes, fashion, politics changed, we see influence or lack thereof. However, outside of this historical/documentary meaning Paraska Plytka Horytsvit’s photographs also have aesthetic value. We can see this in her approach to space and people.”

Today, Plytka Horytsvit’s house is an unofficial museum of her work. Kryvorivnia used to be famous for hosting Ukrainian intelligentsia, Sergei Parajanov filmed his Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors here. And now it is also a place with a unique museum of an interesting artist.

New and best