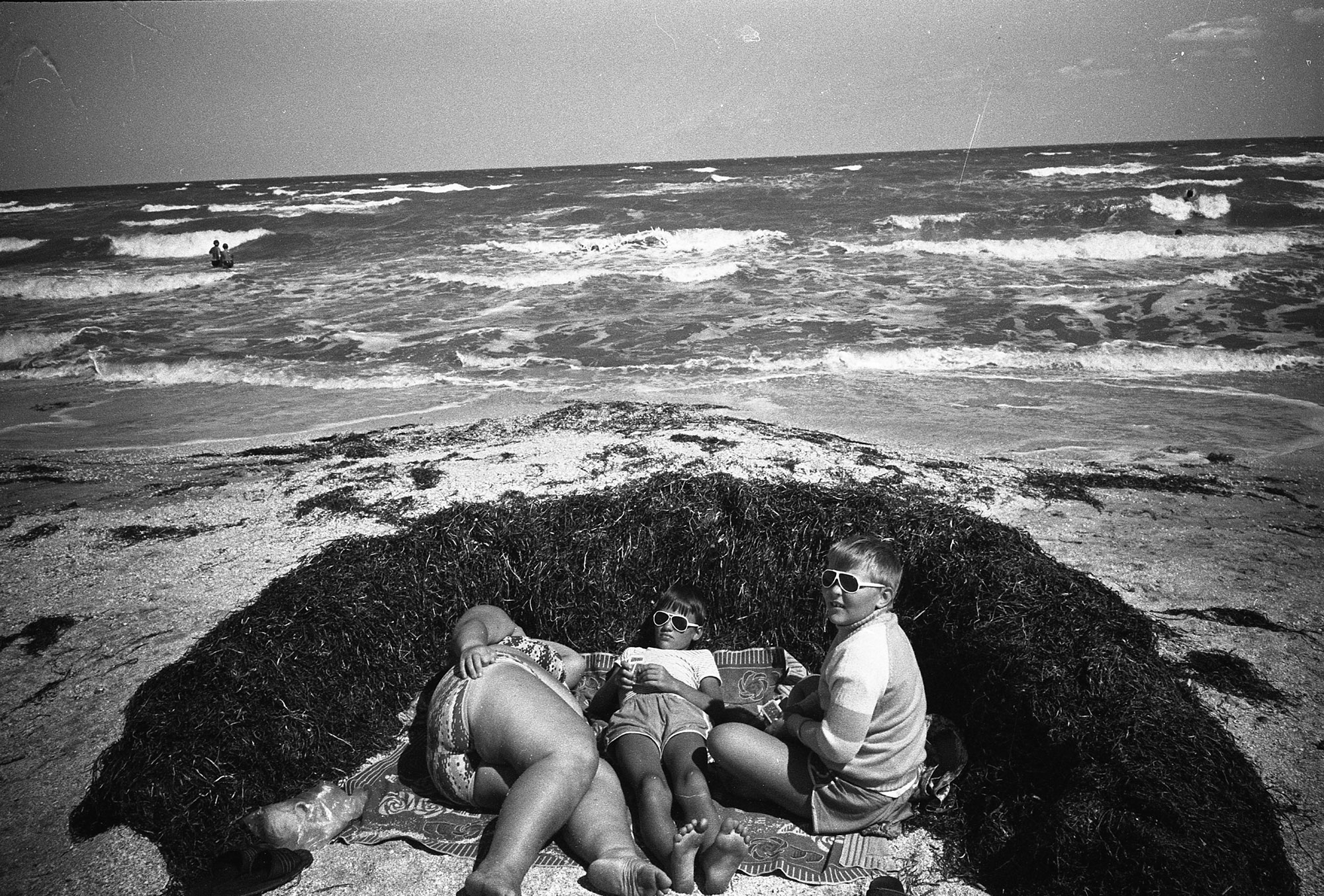

From Birth to Death: Donbas in the 90s Captured by Valeriy Miloserdov

Donetsk miners were captured by many photographers: Oleksandr Chekmenev documented their everyday lives, Arsen Savadov dressed them in packs, Viktor Marushchenko created an art book, and Yevheniya Belorusets accompanied her photographs with conversations with male and female miners.

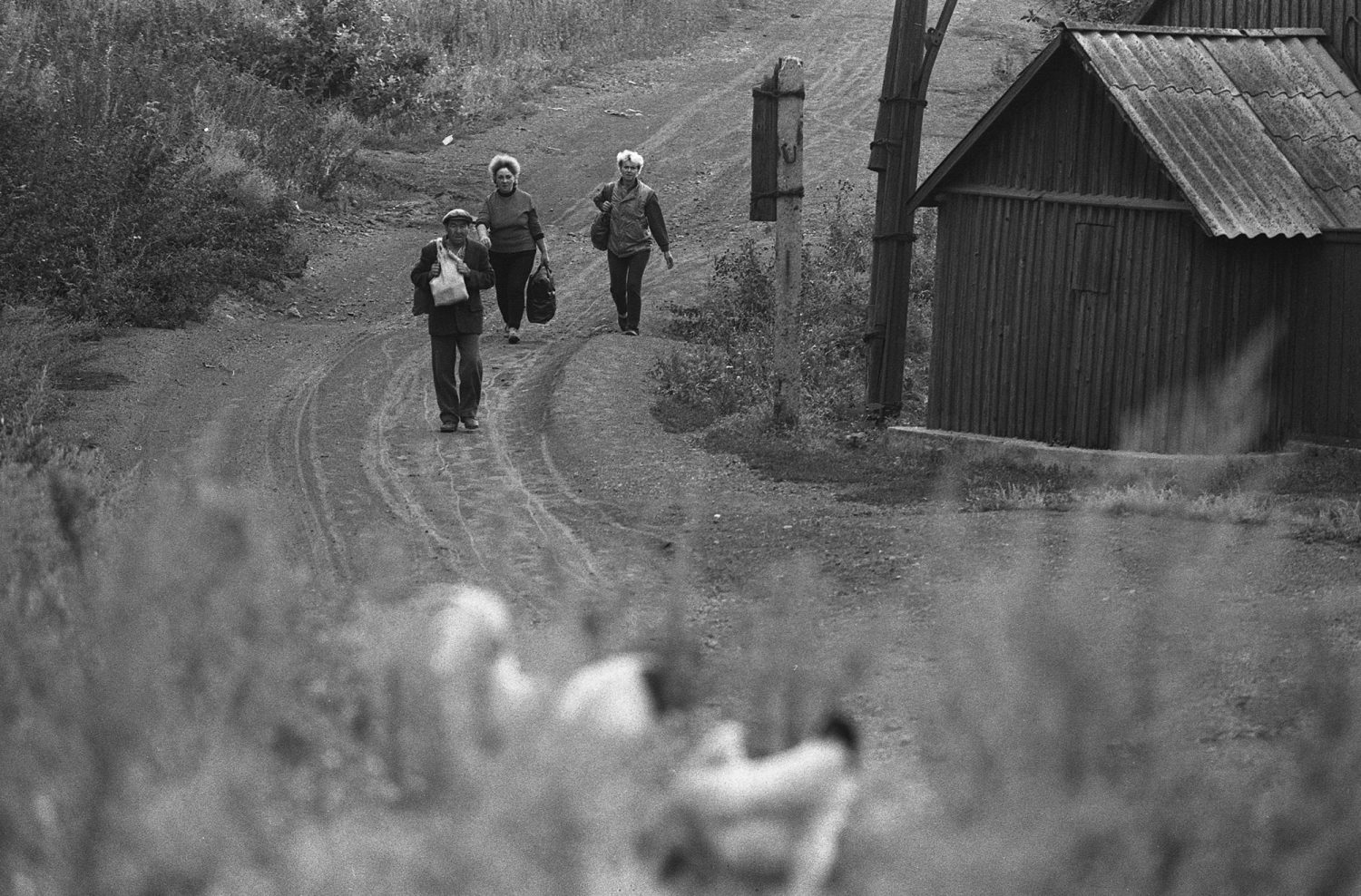

Documentarian Valeriy Miloserdov first arrived in western Donbas in the 1980s and later returned to Donetsk Oblast in 1994, during the height of another economic crisis. He photographed there for the newspaper “Kyivski Vidomosti” until 1999. The series “Abandoned People,” which the photographer created during those five years, depicts a shattered utopia, the death of a hero, and an unwavering desire to live against all odds.

The story that happened yesterday

After graduating from the Journalism Faculty of MDU in 1985, Valeriy Miloserdov got a job as a photo correspondent. He took photographs for Moscow initially and then switched to working for Kyiv in the early 90s.

Since the mid-80s, he found himself in the most interesting places for a photographer. He captured the coups in Vilnius and Moscow, the dispersal of a Crimean Tatar protest in Simferopol, the student “Revolution on Granite” in Kyiv, and the story of the dismantled Lenin monument in Lviv. Miloserdov’s lens captured politicians, activists, and ordinary people seeking understanding, stability, and happiness.

Over the years of his work as a photojournalist, Miloserdov’s archive has transformed into a photographic history of Ukraine. And the most challenging and emotional part of it—the lives of miners—has also found its imprint within it.

Over the years of his work as a photo correspondent, Miloserdov’s archive has transformed into a photographic history of Ukraine.

In various countries, miners had the power of protest. Ukrainian miners protested throughout the country since the late 80s, and it is believed that their strikes accelerated national processes. “An interesting fact,” says Miloserdov, “on the day the Act of Independence of Ukraine was adopted, Leonid Kravchuk’s first trip took place precisely to Donetsk.”

Ukrainian miners protested throughout the country starting from the late 80s, and it is believed that their strikes accelerated national processes.

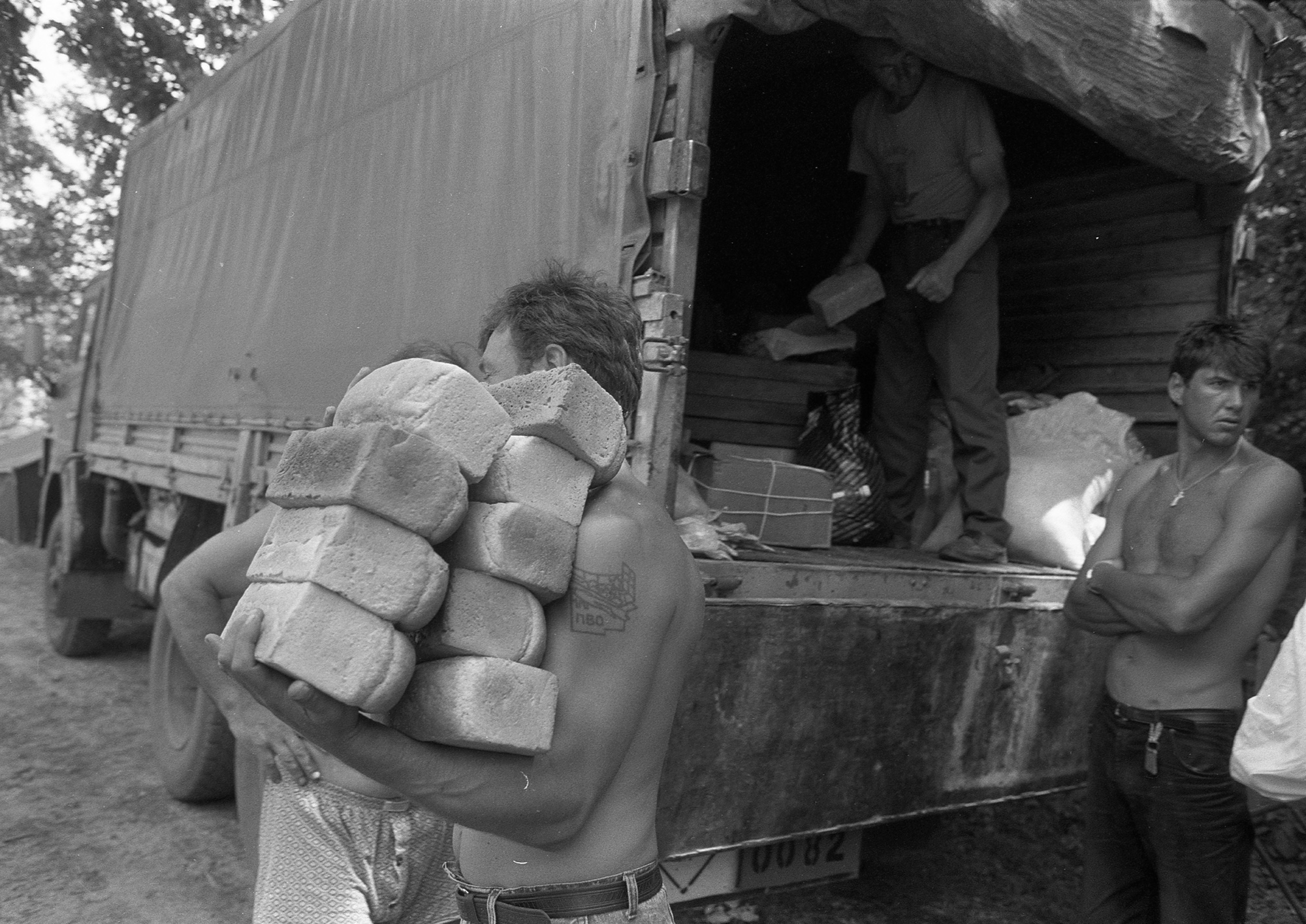

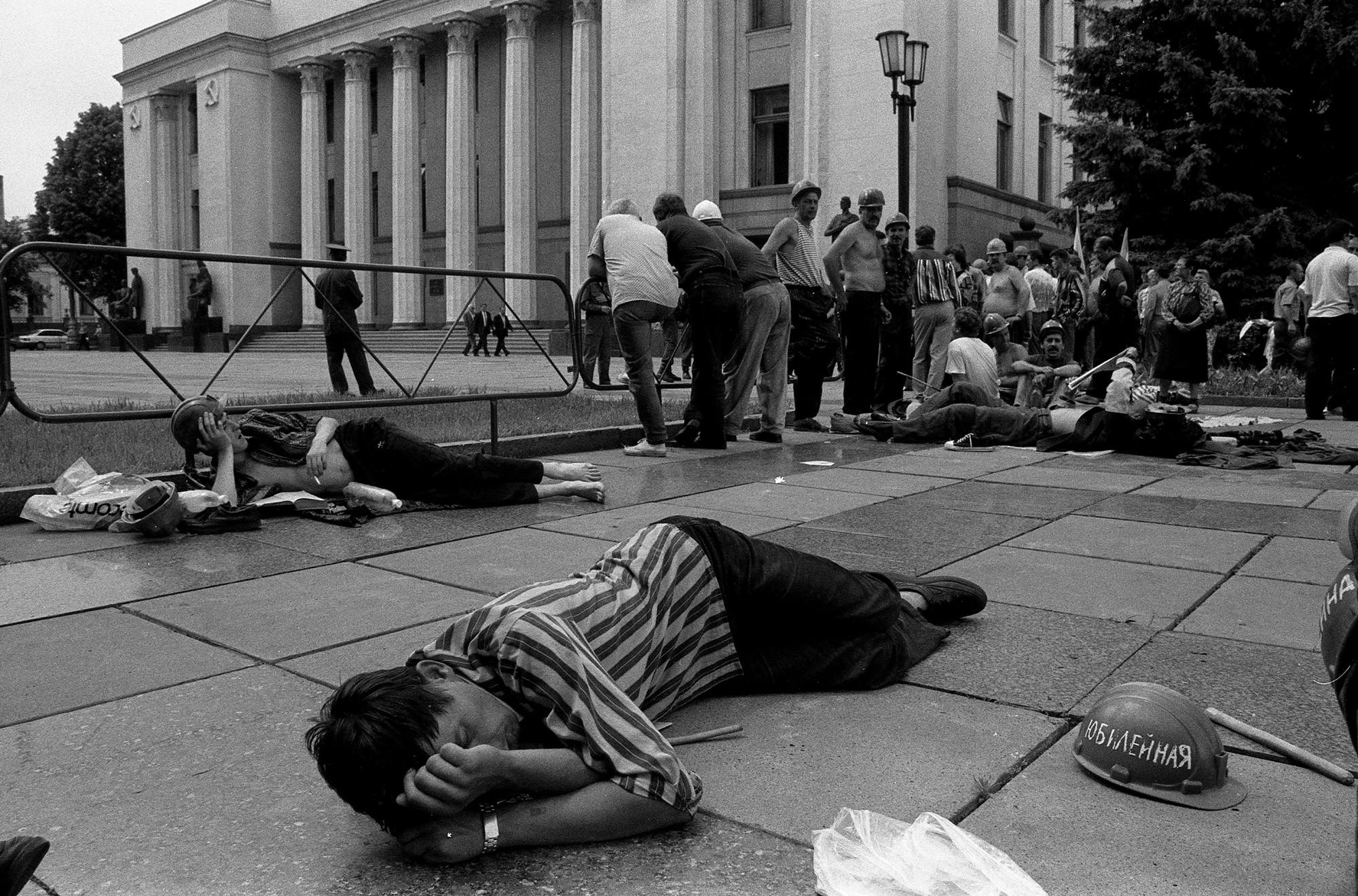

Contrary to hopes of improved conditions after gaining independence, the lives of miners did not improve, and the discontent did not disappear. According to sociologist Kyrylo Tkachenko, the miners’ strikes in 1993 had even greater political potential than those at the end of the 80s. The demands now included a referendum of no confidence in the president and the Verkhovna Rada, granting regional autonomy to Donbas, as well as increasing wages and subsidies.

However, this protest only brought benefits to the mine directors, not the miners themselves. A series of photographs with the poignant title “Abandoned People” speaks louder than any other about the situation in which the workers found themselves.

You’re not welcome here

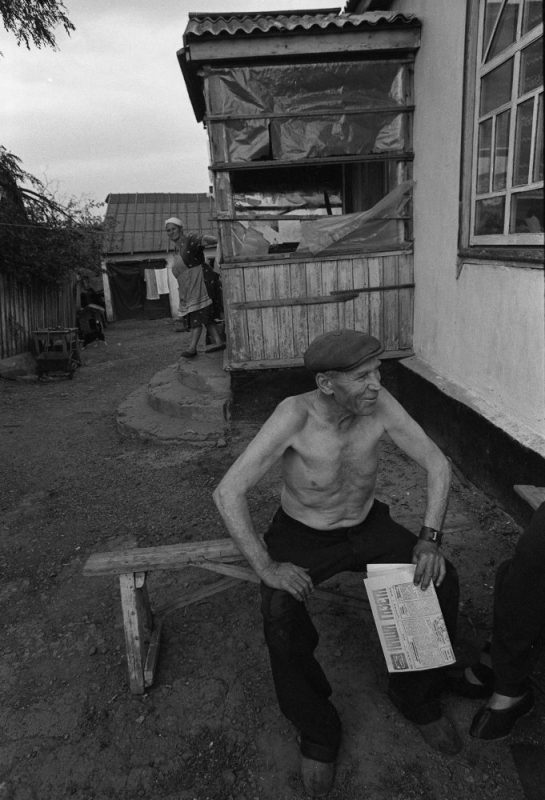

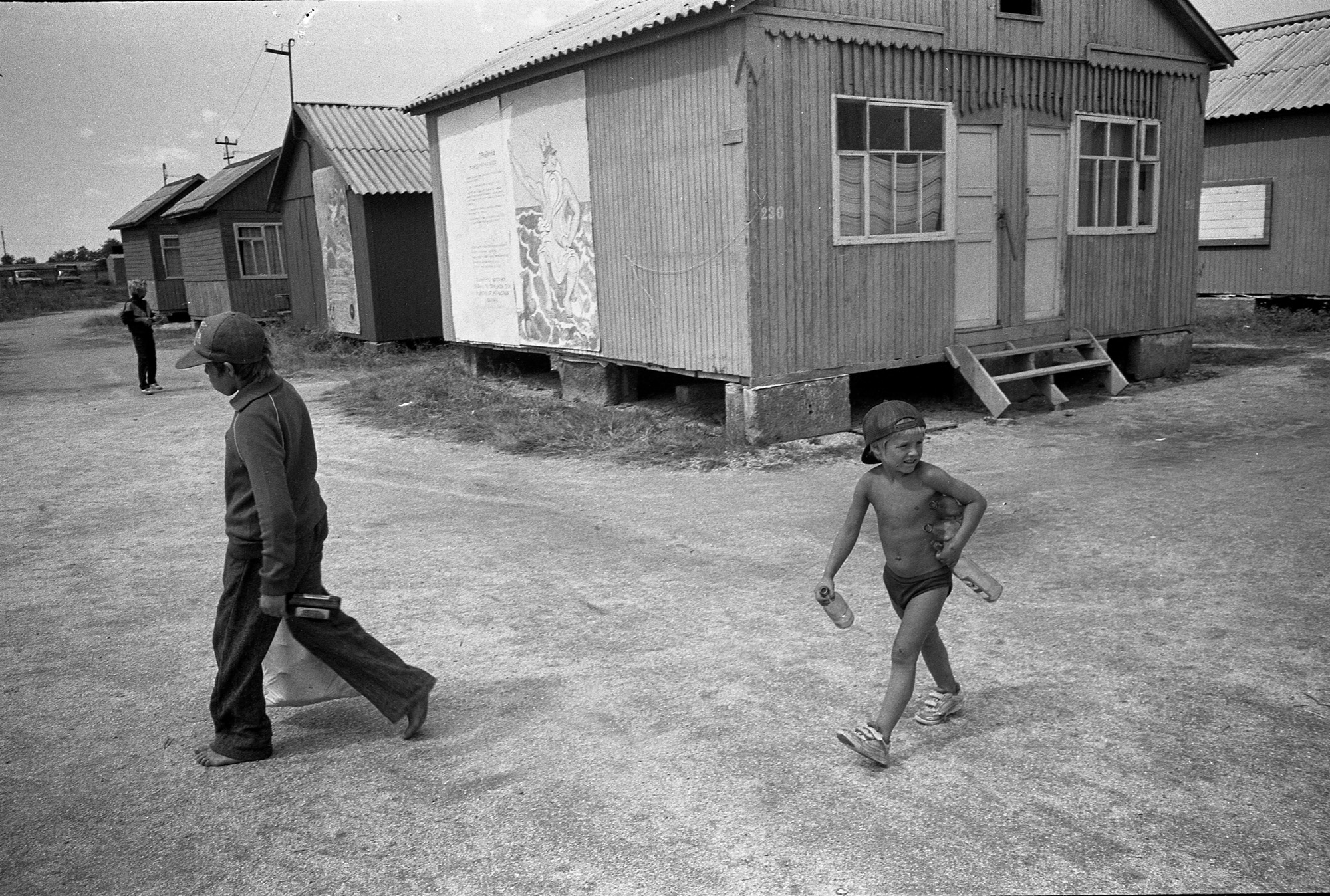

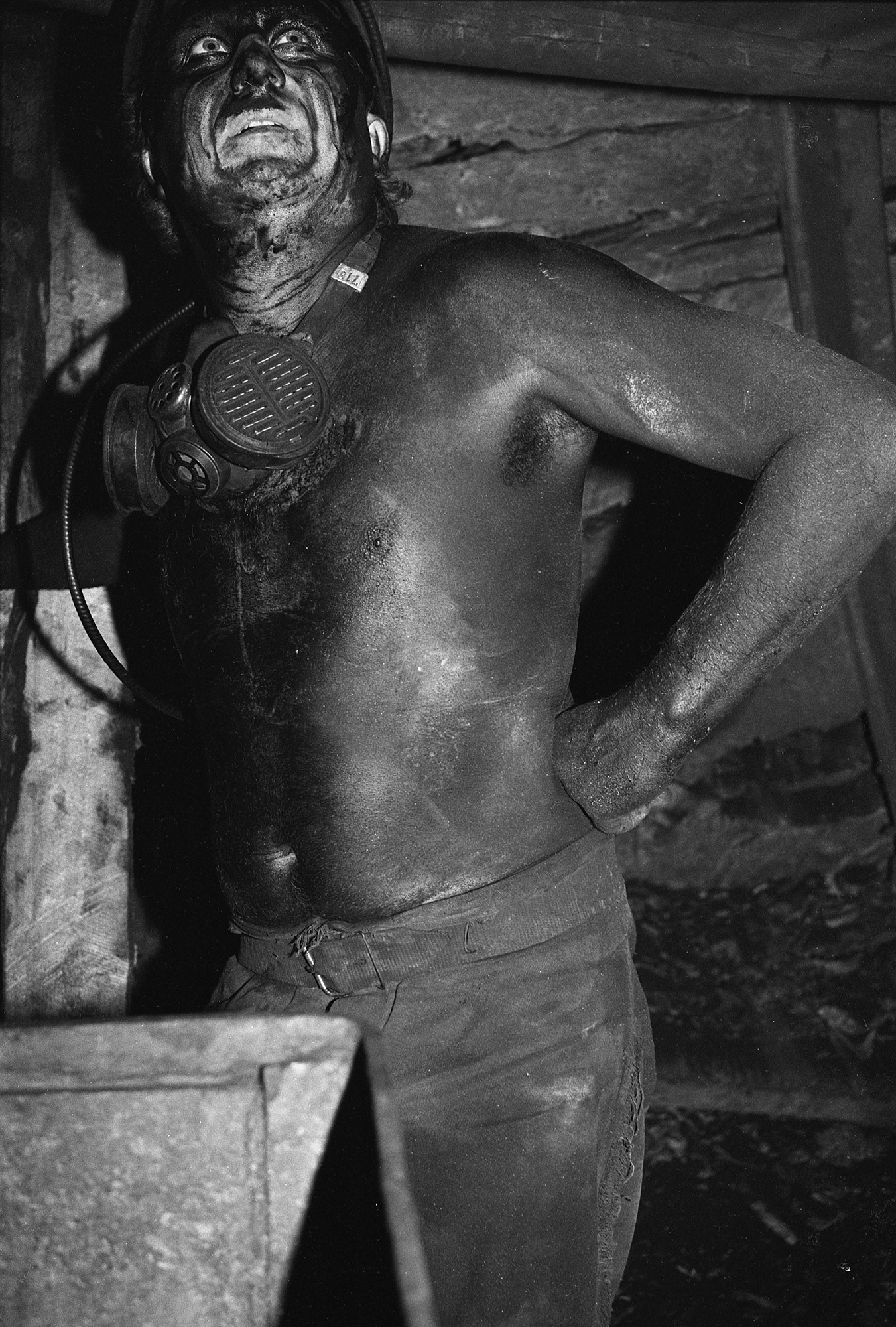

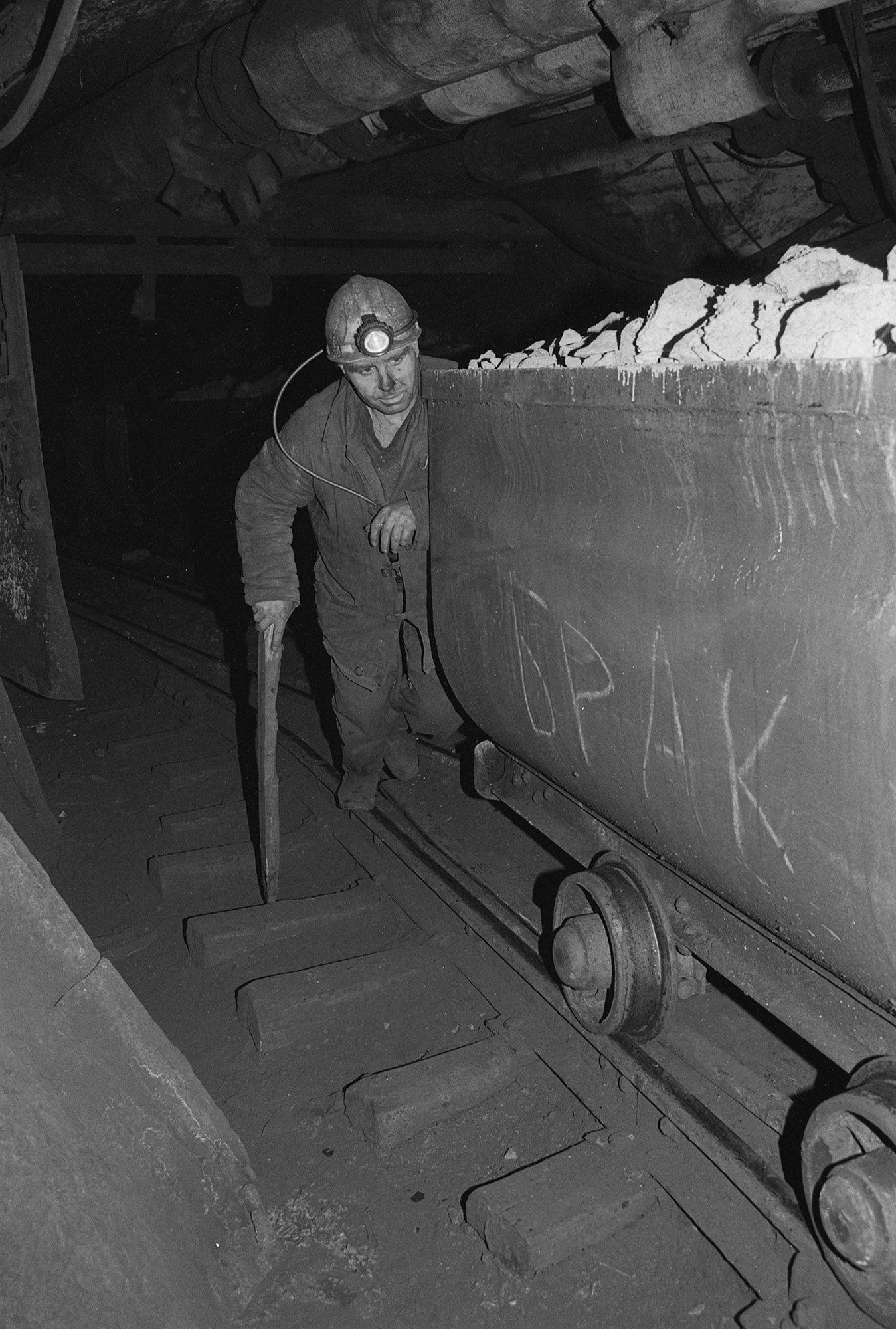

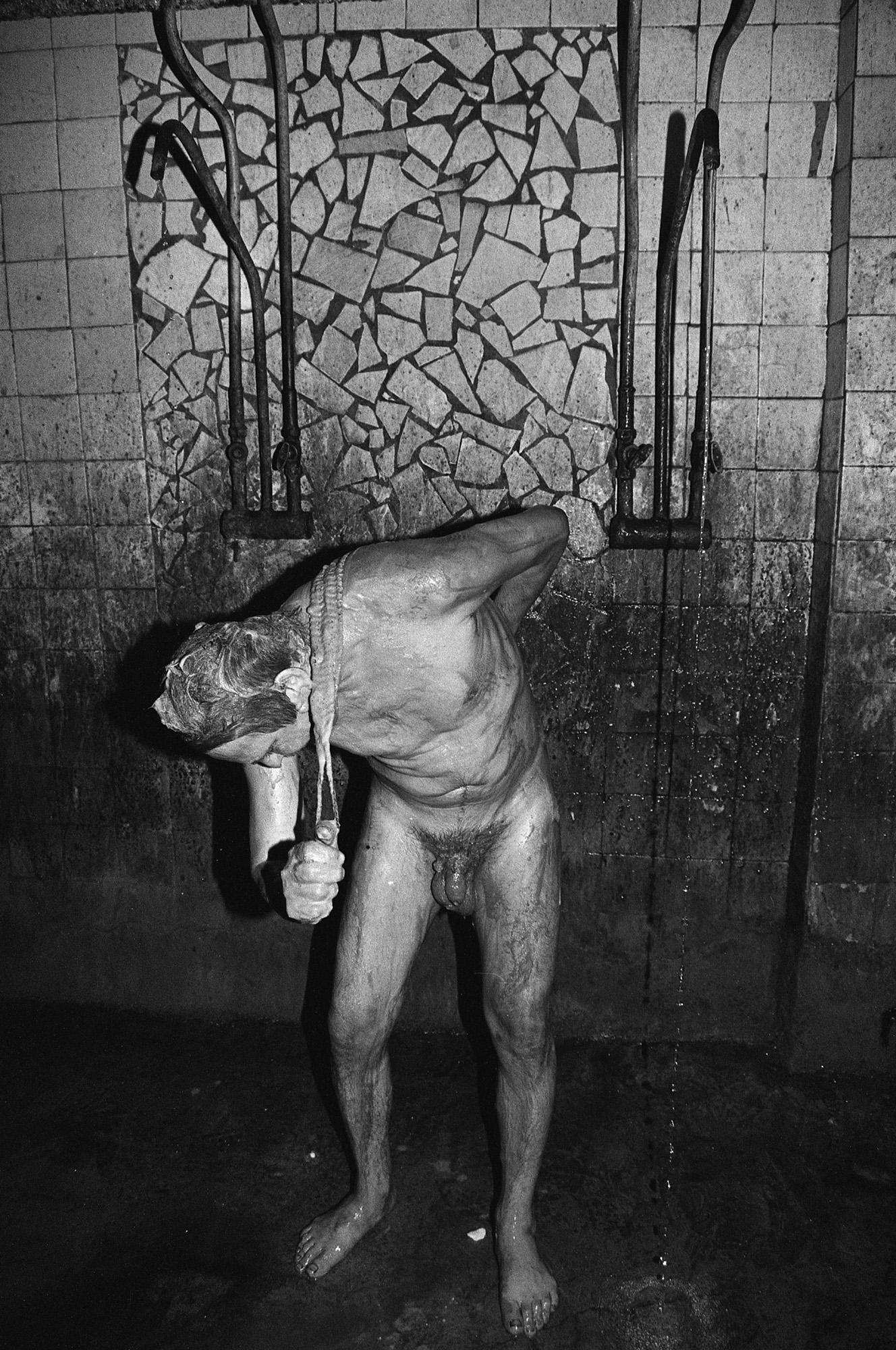

During Soviet times, there was a stereotype that miners were a privileged class living in abundance or even excess. However, when Miloserdov arrived in Donetsk in the early 90s, he realized it wasn’t the case.

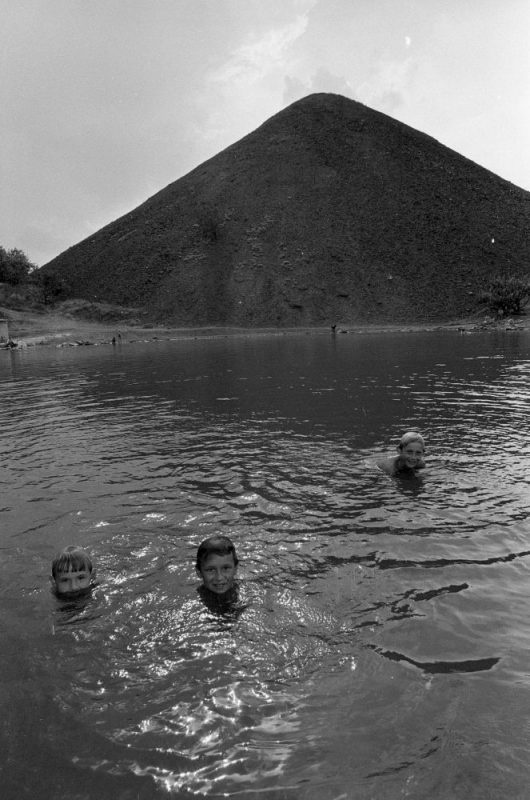

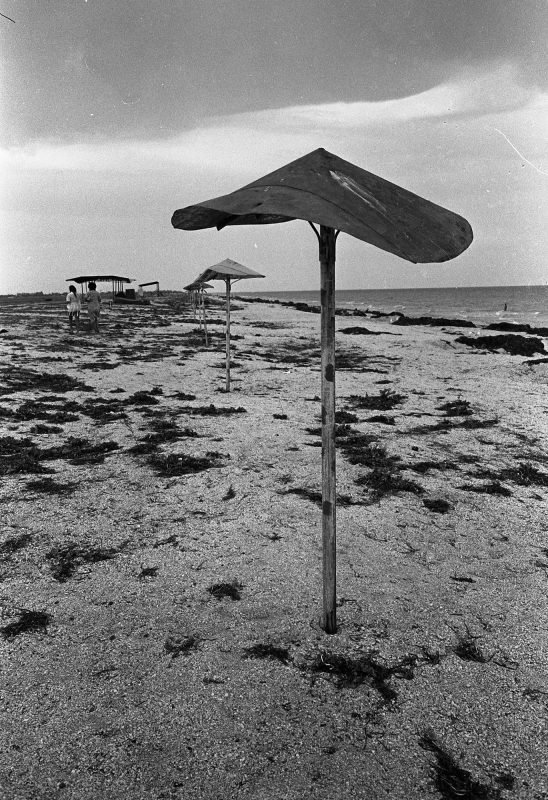

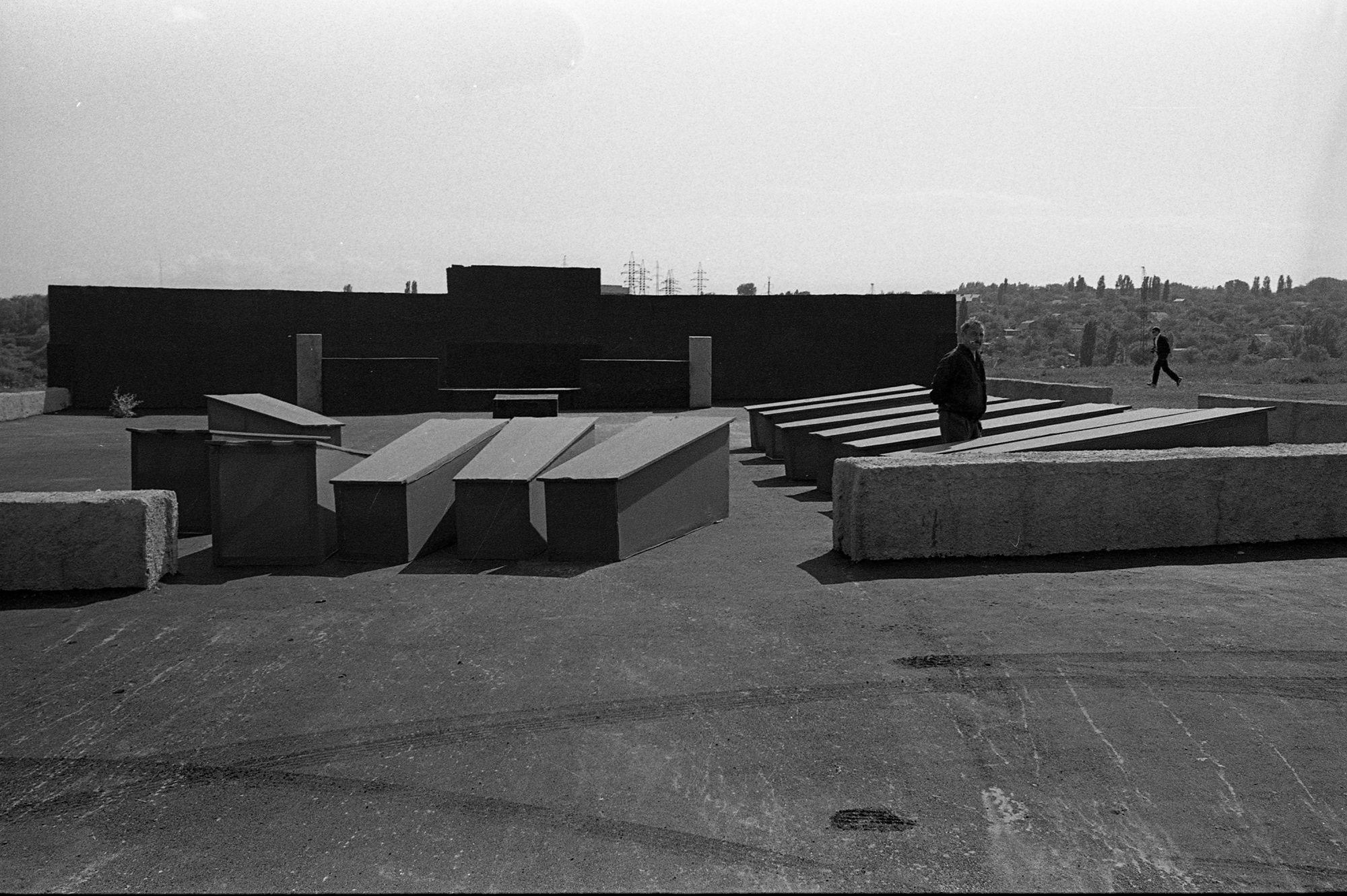

One of his first photographs was a panorama of the city. Seeing the deserted gray landscape, the photographer immediately drew parallels with Pripyat. It seemed that life had come to a standstill, and people felt out of place. The urban landscape, poverty, and meager living conditions didn’t fit the model of mining glory.

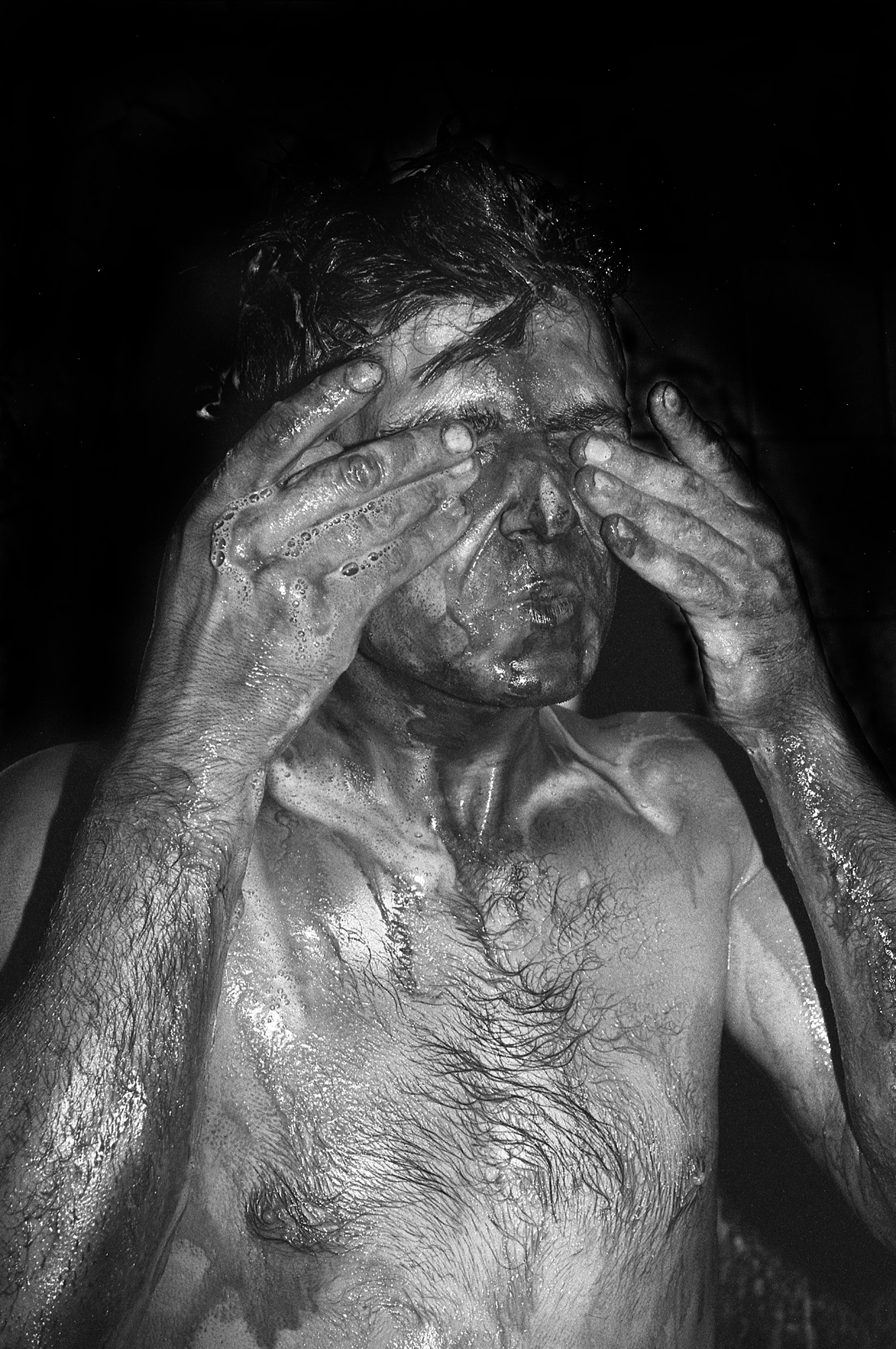

Miloserdov admits that it was initially difficult for him. Miners were quite a specific group: they had a strong bond among themselves but were wary and distrustful of outsiders. To become “one of them,” he had to prove that he wouldn’t cause harm and wouldn’t use information against them. In one interview, Miloserdov shared an incident from the early days of his photography: “When I was crawling through the coupling of two mine cars with my camera equipment, a cry rang out: ‘Come on!’ And seemingly out of nowhere, tons of coal dust rained down on me. I got buried between the two carts, barely managing to hide the camera under my overalls. When I crawled out, I saw that the miners were openly laughing at me. They did it on purpose. At first, I didn’t understand. My initial reaction was to start laughing along with them. Then the foreman said, ‘Let’s get to work.’ The miners, as if on command, stopped laughing.”

According to Miloserdov, after that incident, it was as if an “invisible seal,” a mark of approval, had been placed on him. He was now considered “one of them.” From then on, the photographer was able to capture whatever he wanted. He managed to adapt not only to the harsh conditions but also to the temperament of the miners.

Photography as Diagnosis

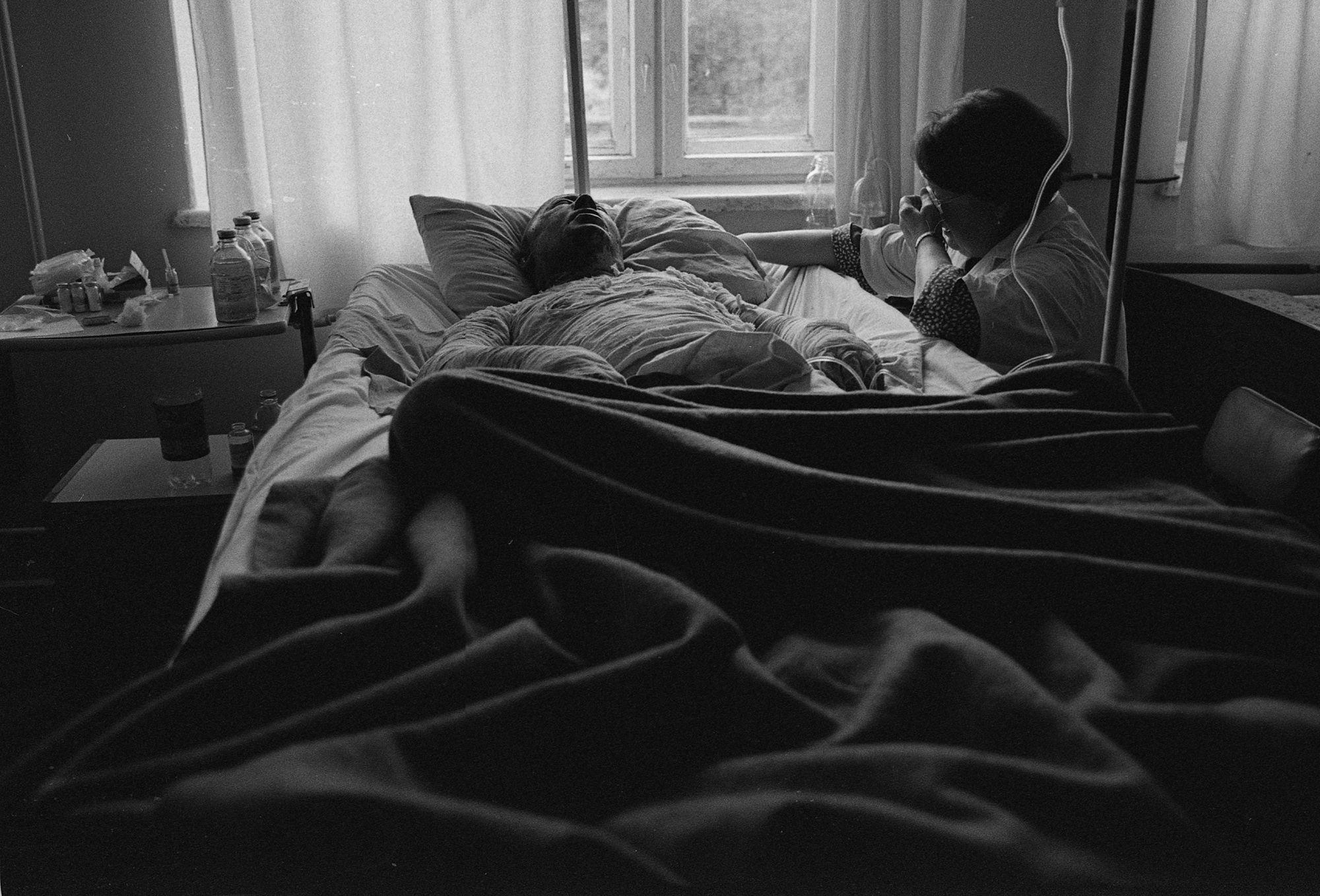

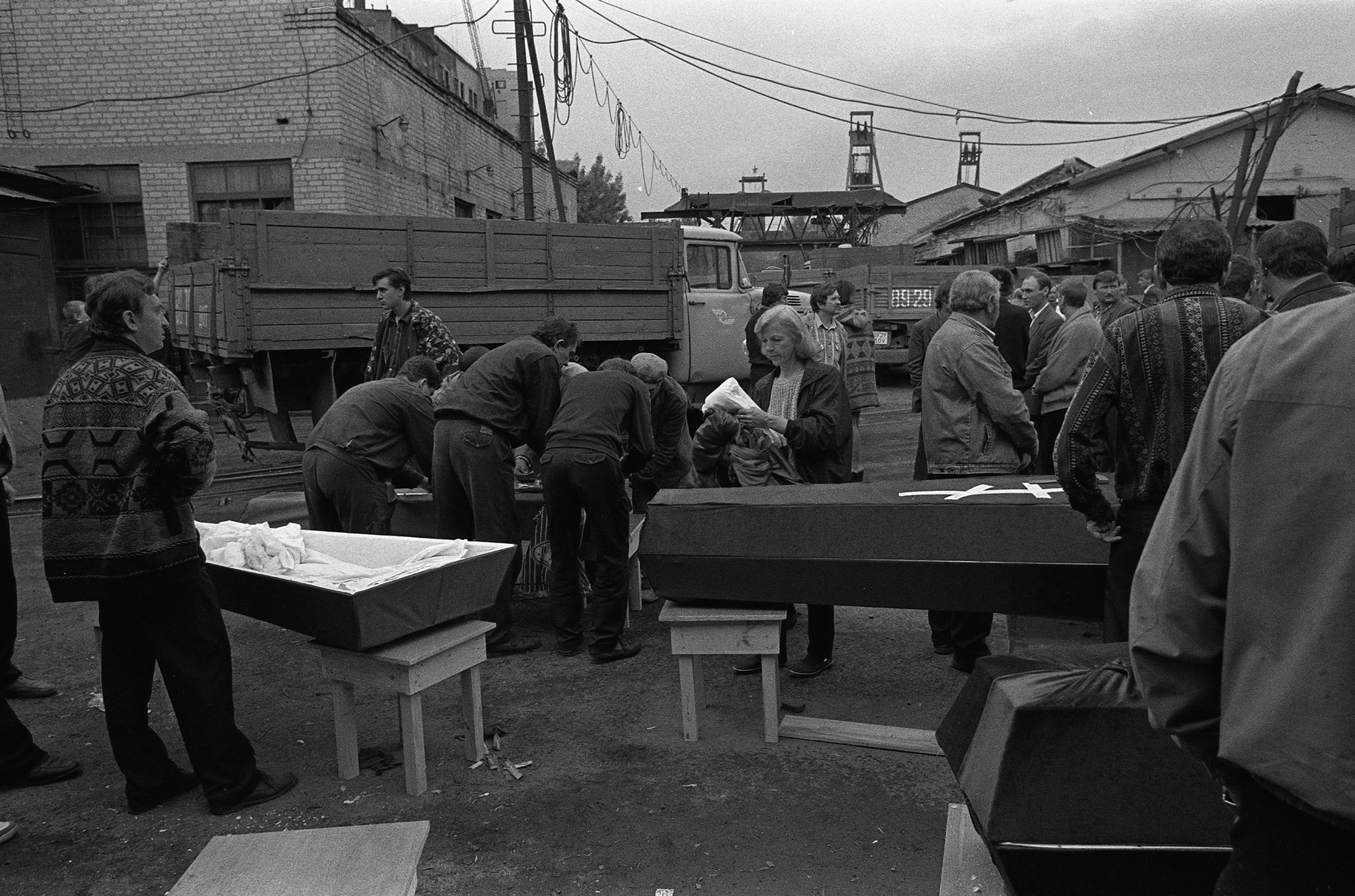

The closest encounters with death struck the photographer the most. Among the miners, there is a high mortality rate in the workplace, yet despite knowing this, they still descended into the mines. Moreover, every morning they would pass by the cemetery on their way to work. This could not help but influence people: constantly facing death, you inevitably develop a different attitude towards it.

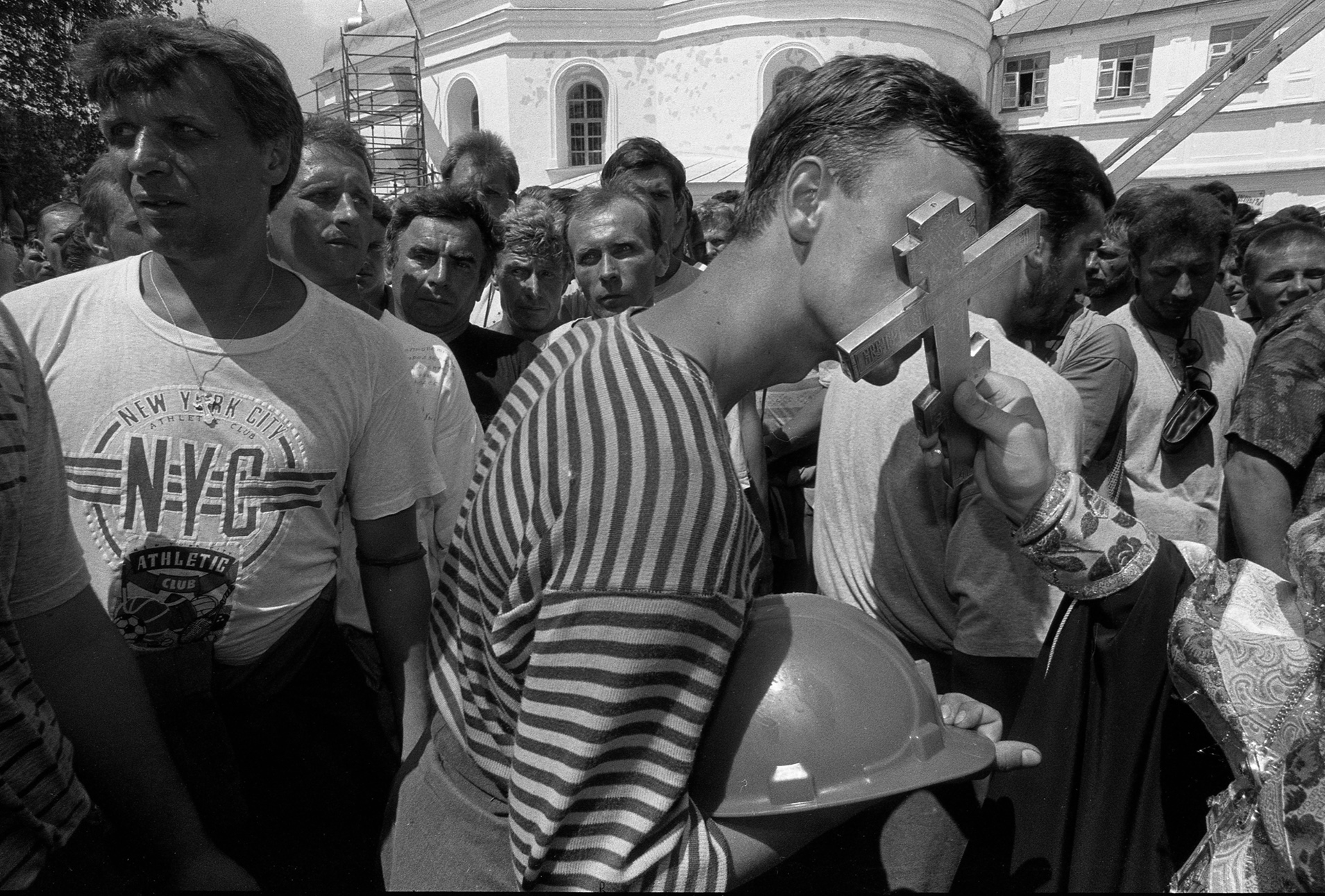

In Miloserdov’s photographs, the entire life of the miners is captured—the joy of childhood and the sadness of aging, the boldness of protest and the hardships of everyday life, the support of faith and the pain of disillusionment. The photographer captures every aspect of their lives, empathizing with all his subjects. Following the thoughts of James Nachtwey, Miloserdov believes that the essence of the profession is to stand with those who are oppressed and become their voice.

The photographer captures every facet of life, empathizing with all of his heroes.

Perhaps photographers documenting the Great Depression in the US found themselves in a similar situation. They revealed the real America—not the face of a successful capitalist from glossy magazines, but the faces of migrants and the impoverished who had lost what little they had. Similarly, the series “Abandoned People” depicts a “life against all odds” and shows it to those who are ready to bid farewell to utopian notions.

The series “Abandoned People” portrays “life against all odds” and showcases it to those who are willing to part with utopian ideals.

In one of his interviews, Miloserdov compares documentary photography to medicine. “It’s not an institute of beauty or therapy, it’s the trauma department in an emergency hospital. You try to diagnose a sick society. And you need to clearly understand the meaning of your work,” he said. The same happened with “Abandoned People.”

The photographs featuring Donetsk miners were published in a series of articles in “Kyivski Vidomosti” newspaper and were also showcased in competitions and exhibitions. For his series, Miloserdov was awarded a special prize by the jury of Grand Prix Images Vevey (Switzerland, 1995).

New and best