The Internet Ruins Lives: Who Makes Money Off Of Mugshots

They can harm, rob or make unfounded accusations, but at least they do not post your photos on the Internet. If you use your imagination, this could be the argument in favor of law enforcement agencies in some countries over the ones in the US.

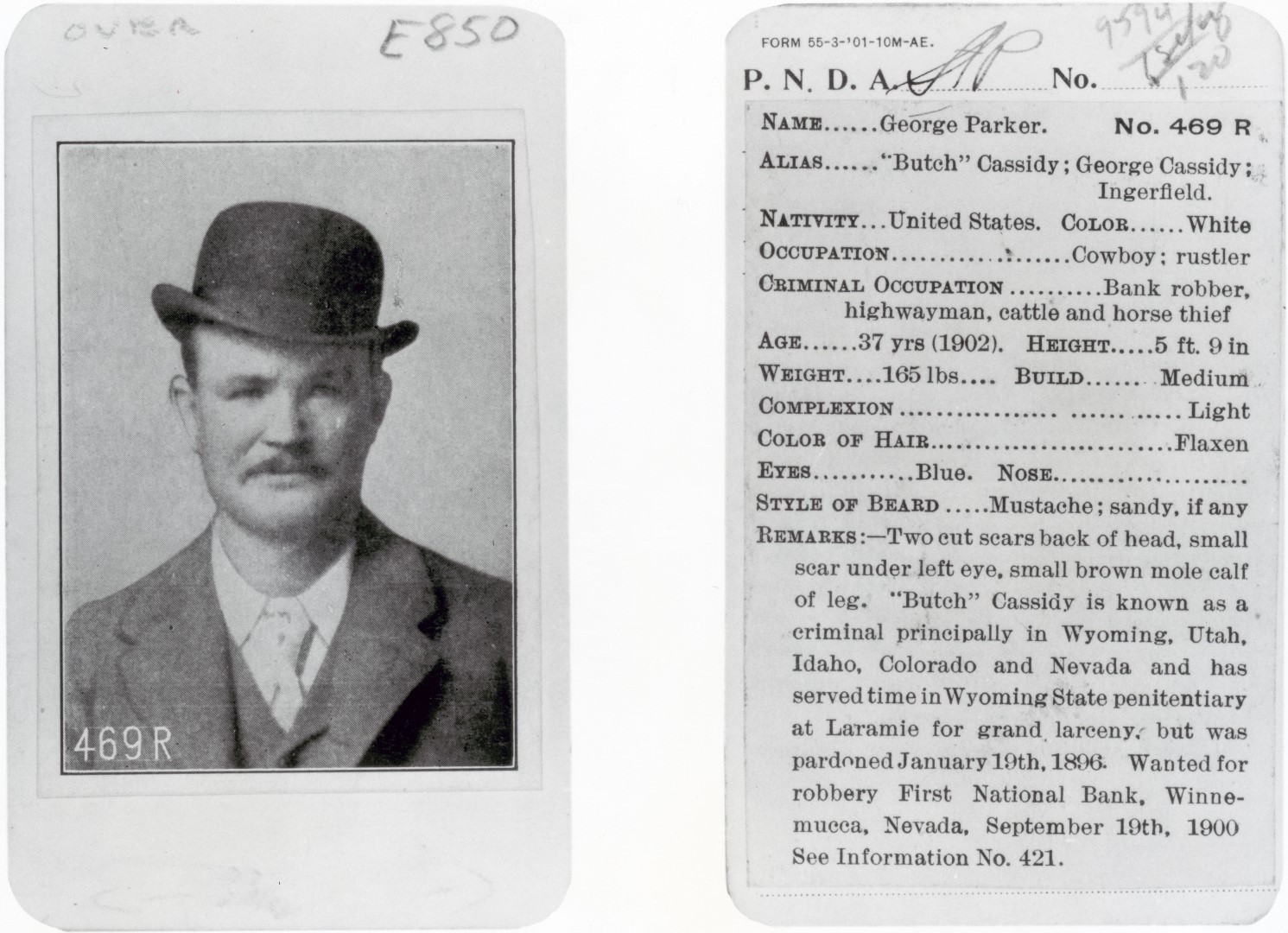

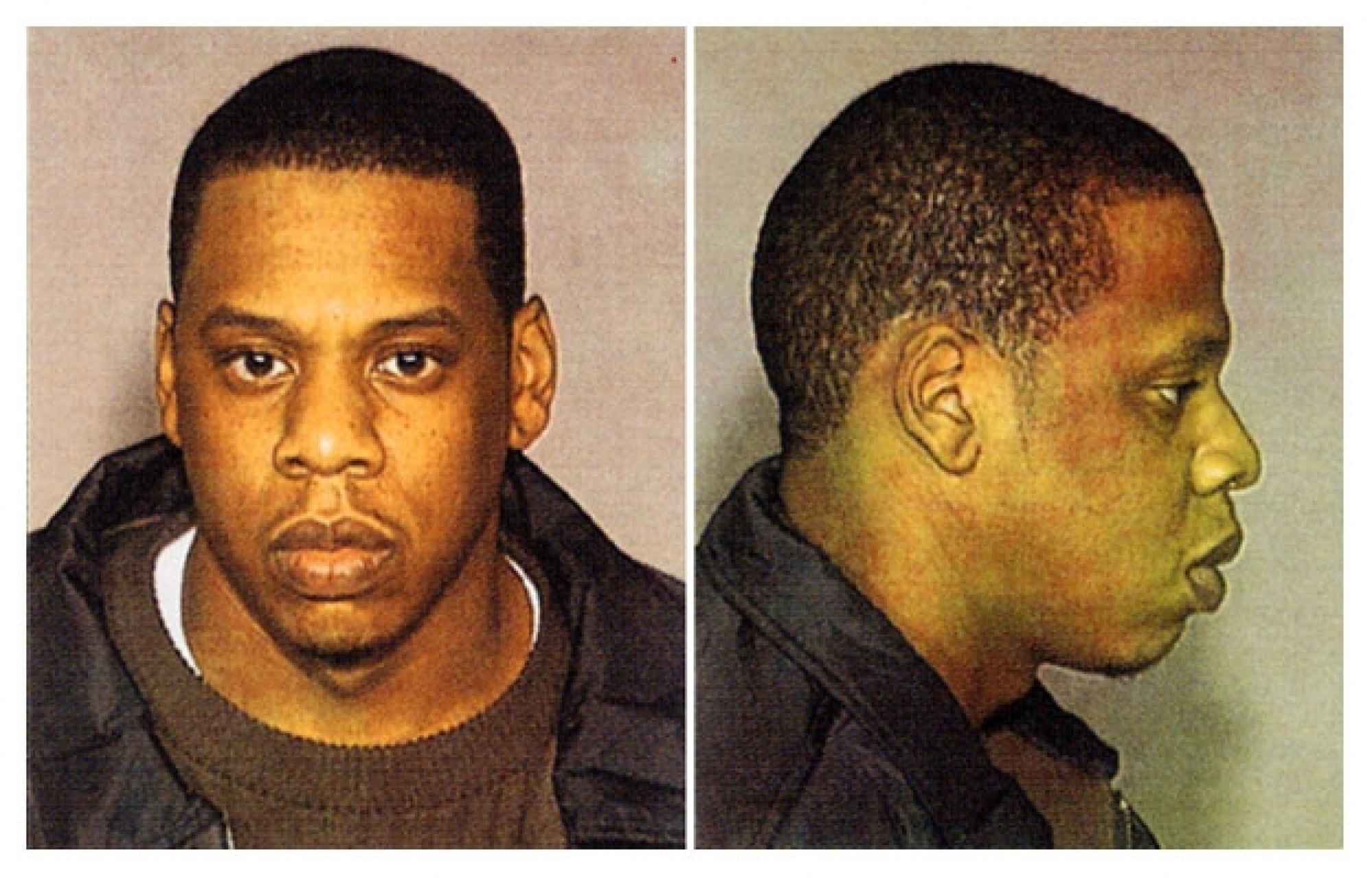

Portraits of the detained — mugshots — are treated as freely available information in the US. They are published on the Internet by police departments and are capable of ruining the reputations of even those whose names are officially cleared from any wrongdoing. Several dozen online services have been built on this business model, reminiscent of a kind of extortion.

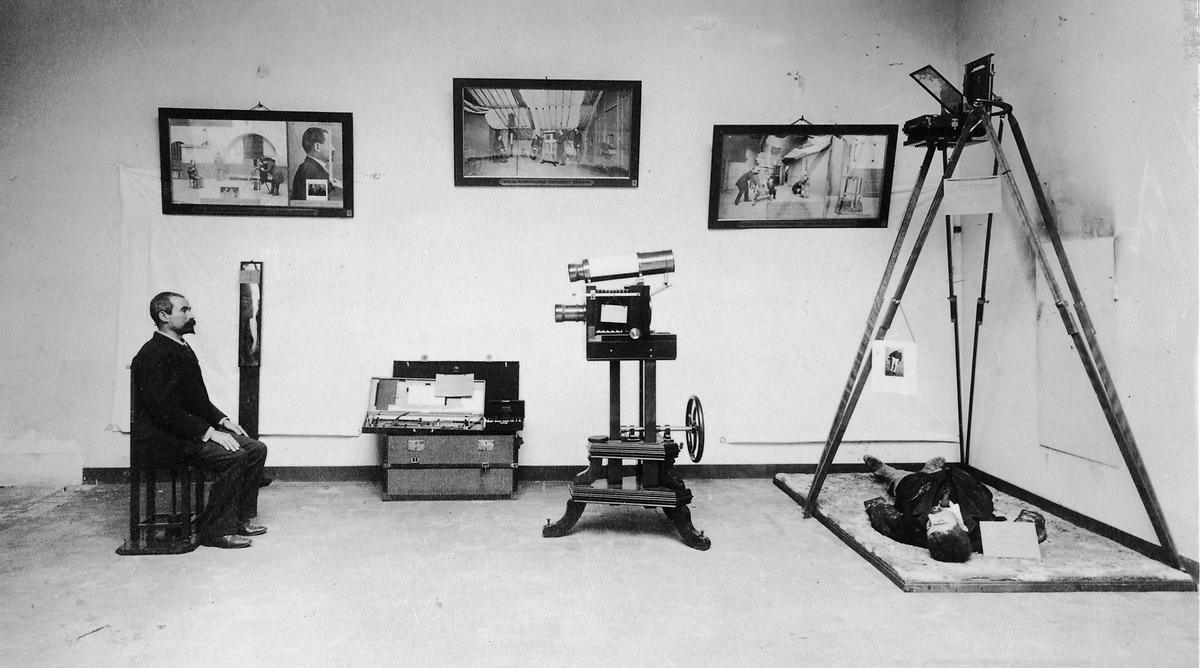

According to the FBI, there have been around 250 million arrests in the United States over the last twenty years, and each suspect affiliated with a crime has been photographed. Not all of these shots end up on the Internet though. The government does not regulate this, so each mugshot’s fate rests in the hands of local authorities.

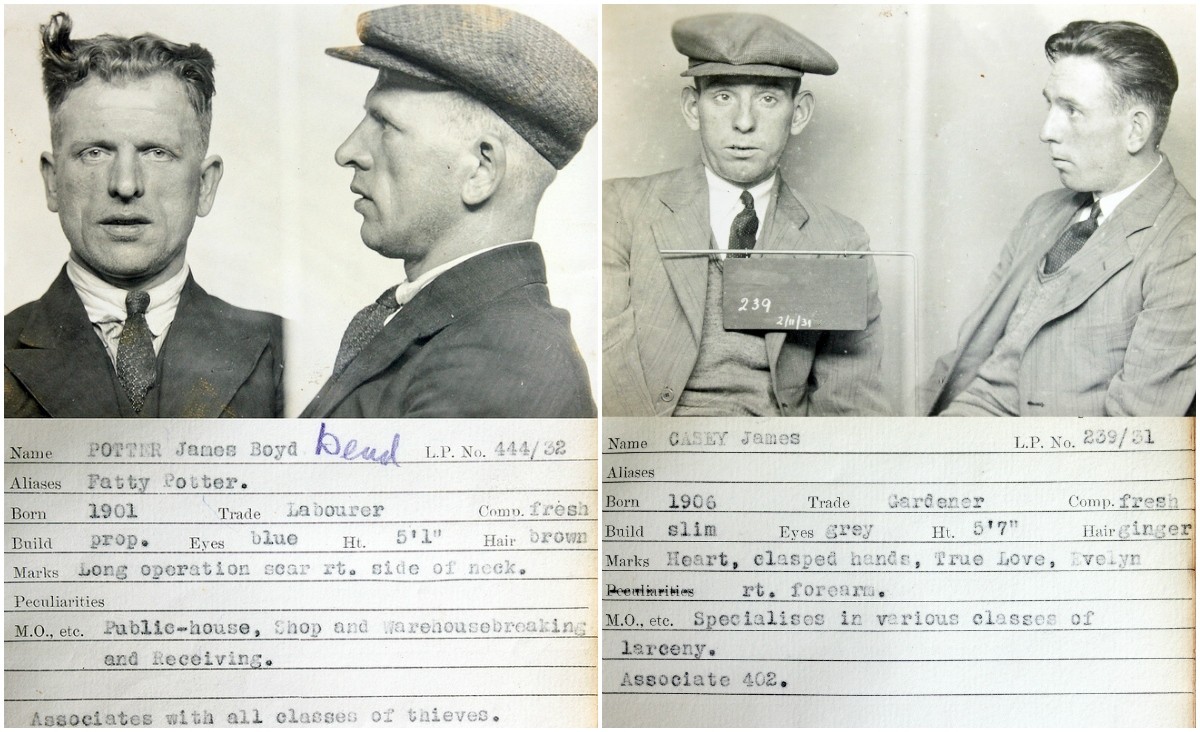

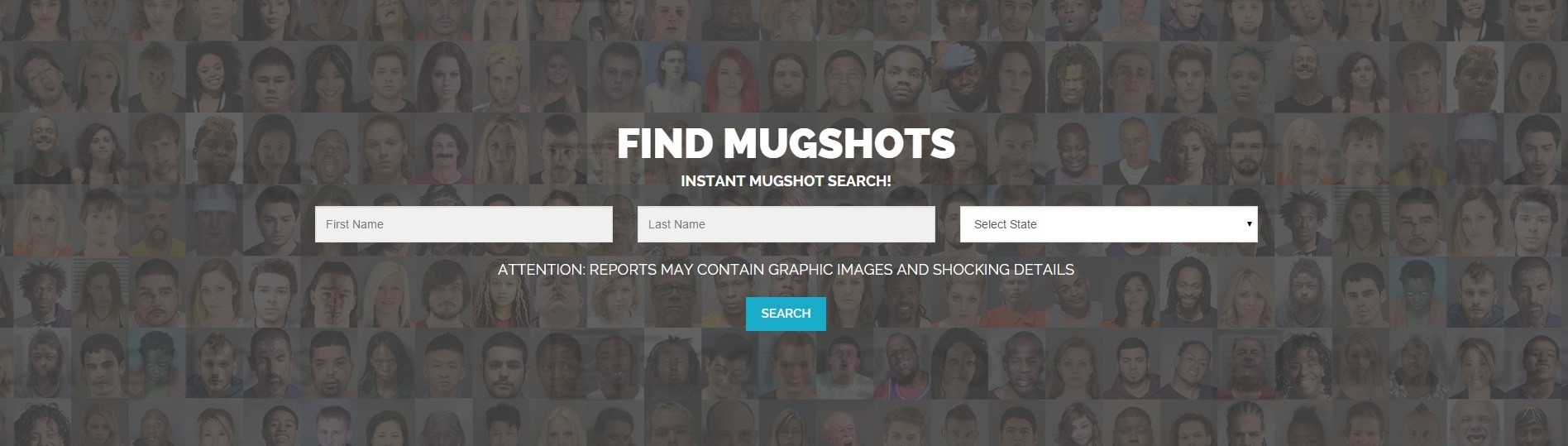

Around 50 US police departments and sheriff’s offices keep records in their own online databases. Almost one hundred commercial Internet projects automatically crawl the databases and gather files in chunks with new shots and information about the circumstances of arrest. Of these, the largest ones proclaim having tens of millions of mugshots in their databases.

Ten to twelve thousand records are added each day.

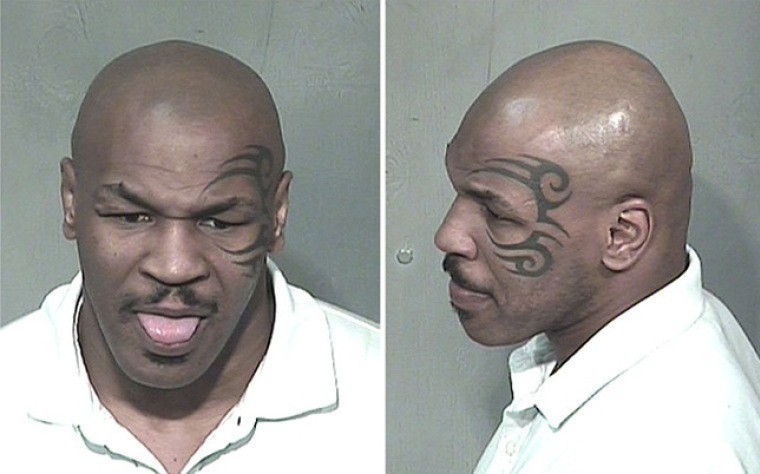

This isn’t just embarrassing; it can ruin your life. Employers, banks, colleges and landlords undoubtedly check their clients, students, partners and employees using these systems. These services will often reject even people who were only held, but not indicted of any crime.

According to research done in 2010 by the University of Southern California, people younger than 23 who have been arrested, but not convicted, of any crime are 23% less likely to finish college and 13% more likely to live below the poverty line, earning $5,000 less on average per year.

This is the reason why many are willing to spend thousands of dollars to erase their mugshots from the Internet.

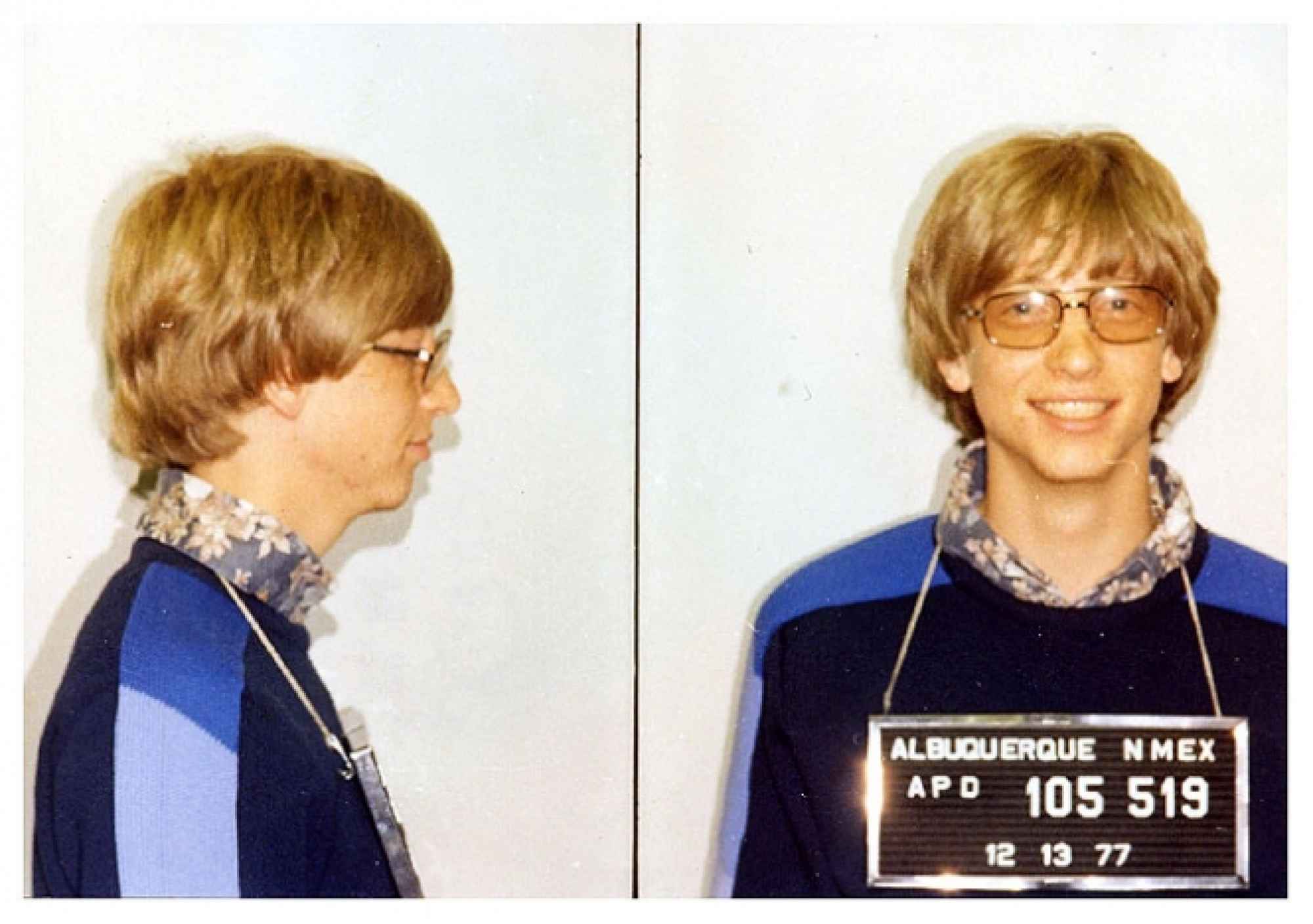

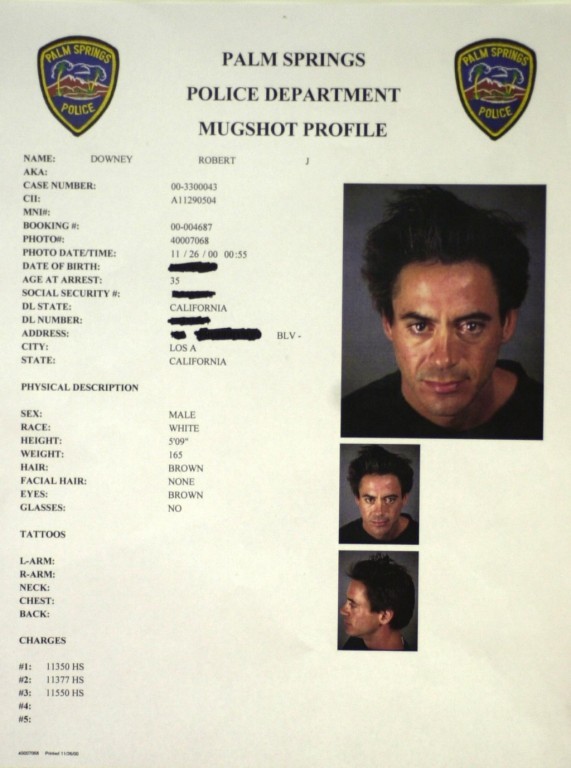

Mugshots had already existed on the Internet for years when, in 2010, Craig Robert Wiggen found a way to make money off of them. He released the site Florida.arrests.org after having served a three-year sentence for stealing clients’ credit card information at the restaurant he worked at. Wiggen had collected four million photos by 2012, released several similar sites with information on people arrested in different states, and his business model has already been copied several times by competitors.

How do mugshot sites make money? First, it has to do with placing ad banners from Google Adwords; the scandalous content brought an active inflow of visitors to the site. Second, through a paid search through the database. Third, by charging fees for deleting photos from general access. A lot of people whose portraits ended up on Wiggen’s Internet services have complained about being bombarded with spam about offers to clear their records for $299.99.

Any of the famous Silicon Valley start-ups would be jealous of this kind of monetization.

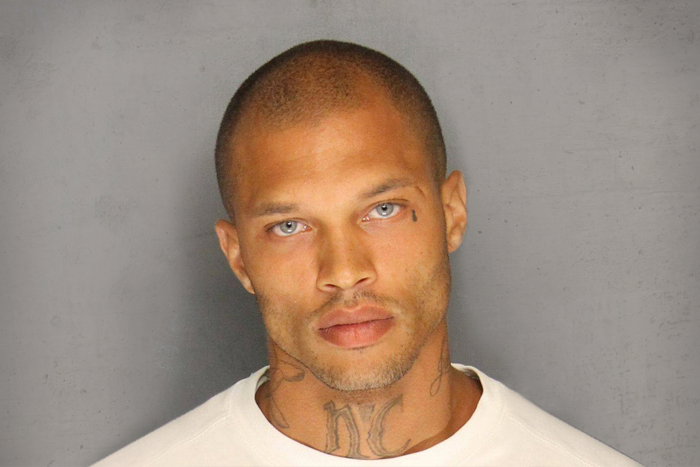

An attempt to prohibit this practice through the courts has failed. The first amendment of the US Constitution protects freedom of speech and publication through the Internet. The work of good journalism – threatening to harm the reputation of big players in the industry – has proven to be effective. In 2013, while working on material about the mugshot business, New York Times’ columnist David Segal approached Google, PayPal, Visa, American Express and Discover with a question about how collaboration with such sites coincides with their self-professed corporate principles.

It didn’t take long to get a reaction. Payment system companies refused working with mugshot collection sites, and Google significantly lowered them in their search results. Now, a record of a person’s arrest is much more difficult to find than it was before, when it was either on the first results page or the number one result when searching for people by name and surname. In a parallel move, lawmakers in several states have prohibited their police departments from keeping Internet-based photo databases, and in some other states Internet resources are obliged to delete photos of people who have not been convicted or have been acquitted in court at the first request.

However, businesses who service people with an understandable desire to hide their history have not been completely destroyed. They have, in fact, taken a new form. “Reputation defense agencies” offer services to delete mugshots from popular collections for prices between $129 and $1,200. They don’t disclose their exact methods, alluding to the fact that they exert legal pressure on the owners of photo databases.

It begs the question of whether the agencies simply pay them for record removal or not. However, there is still a serious reason to believe that sites that publish mugshots and sites that promise to delete them are owned by the same people.

New and best