My Precious: How Much the Life of an American Pilot Costs

The second missile hit right on target and the Douglas B-66 exploded, killing five crew members. Seconds earlier, navigator Iceal Hambleton catapulted. He was now hanging on parachute straps — alone above the jungle and paddy fields, above the muddy river and thirty thousand North Vietnamese soldiers on the biggest offensive mission of this war.

Neither then, in the sky, nor later, after he broke his hand when he hit the ground, was Hambleton going to surrender. He had three major reasons to fight for his life, hide, shoot to the last round, and break through to find friendly troops.

First one — he had nine months left before his retirement. Second — if he were to be captured, he would be tortured.

In 1966, a POW named Jeremiah Denton, Commanding Officer of Attack Squadron, was made to do a TV interview. Speaking about detention conditions, he blinked the word ‘torture’ in Morse code.

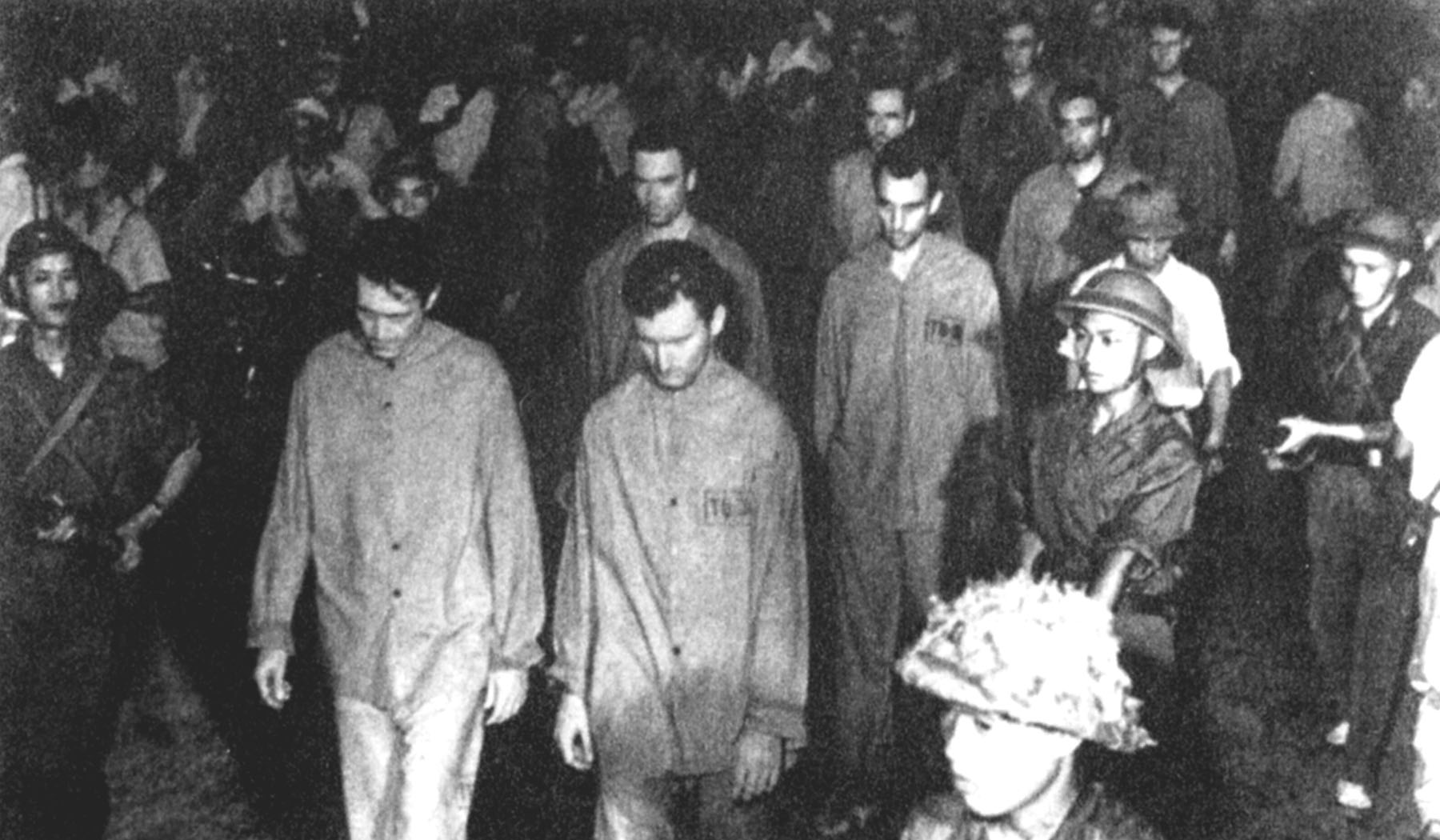

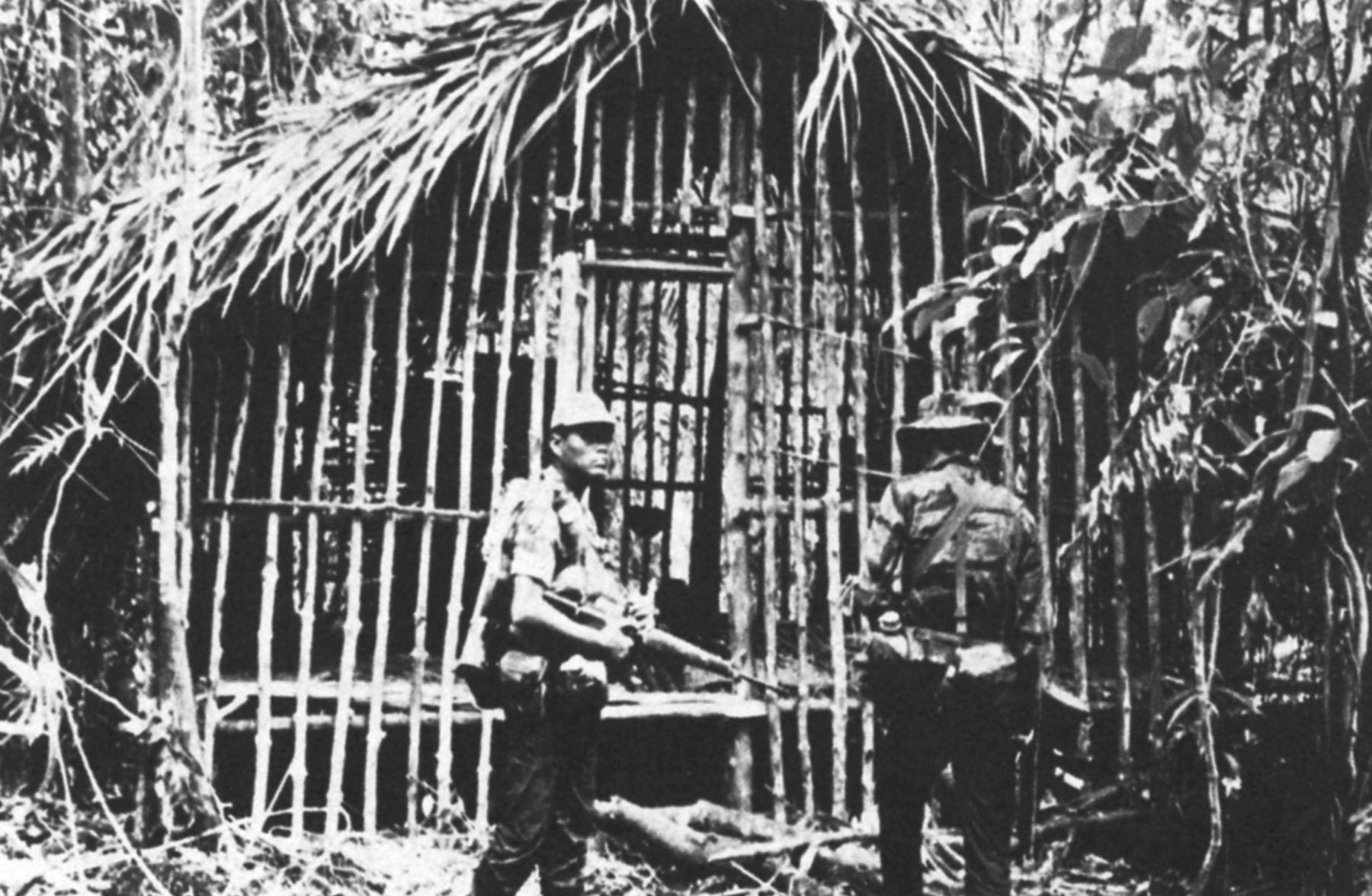

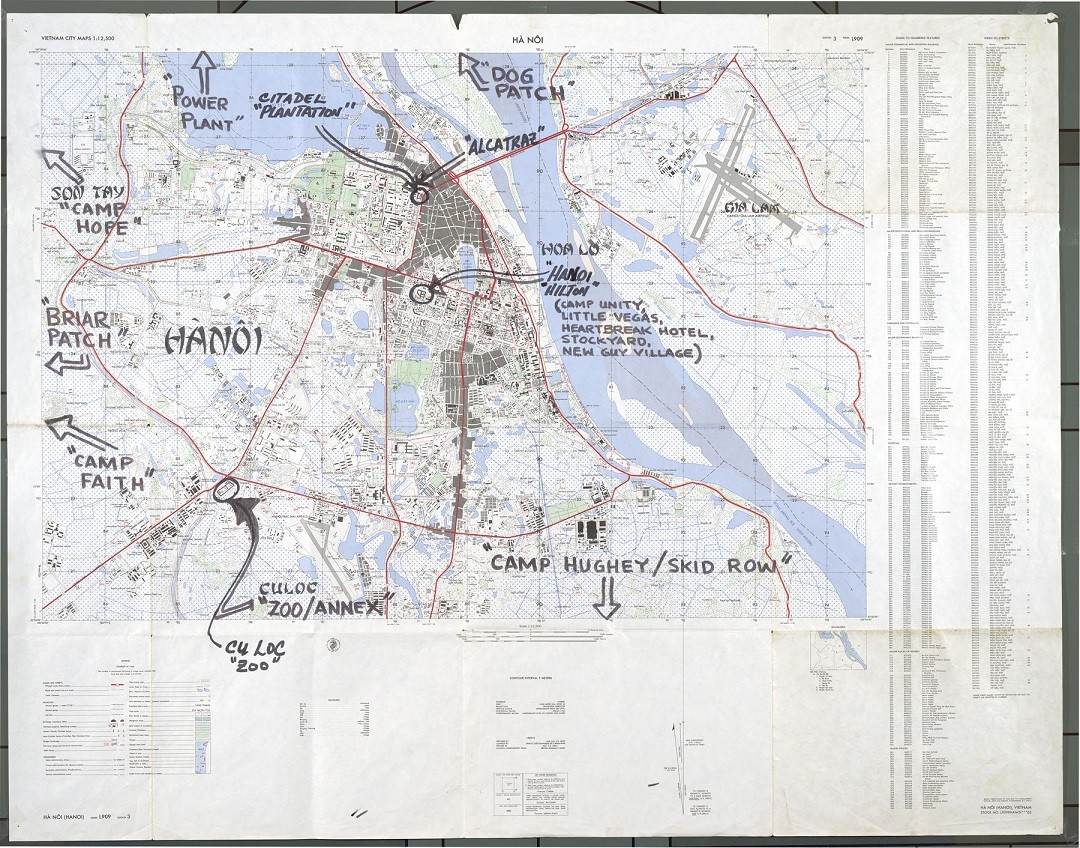

It was 1972, the next year the US will withdraw their troops, and Vietnam will free six hundred POW survivors. They will come home to tell about bamboo cages in the forest concentration camps, Hoa Lo Prison cells, shackles, torture racks, and flogging.

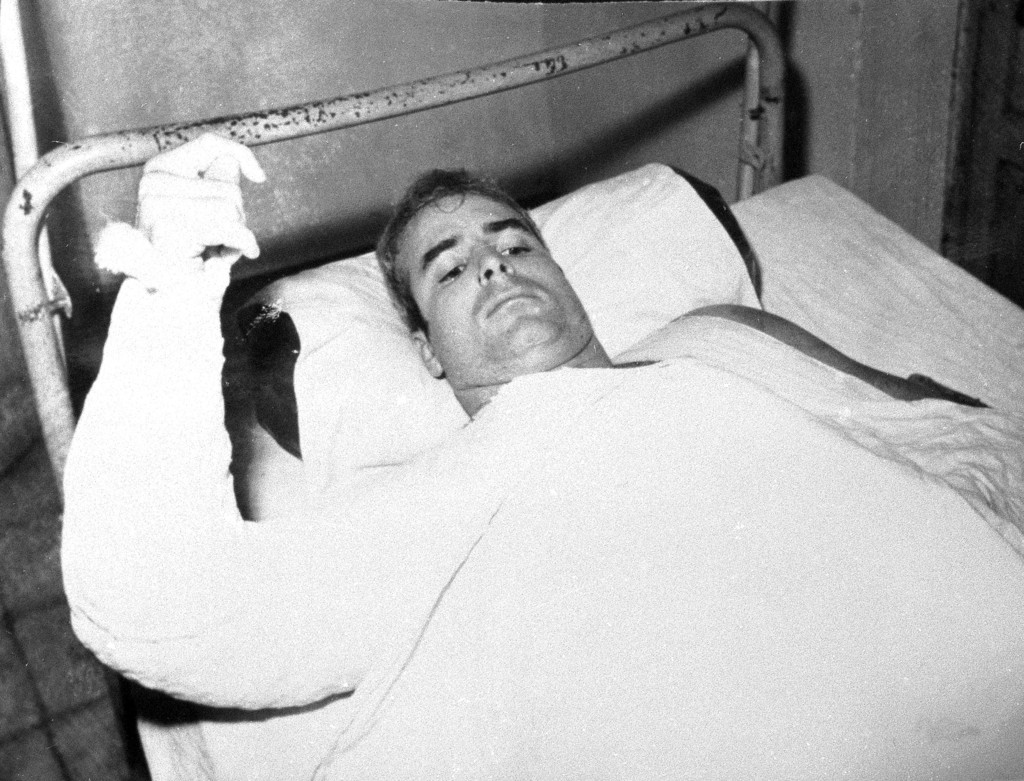

“I had learned what we all learned over there: Every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine”, — John McCain.

Pilot John McCain, a future candidate for President of the United States, will also come home. A son of an admiral, he experienced special treatment from the guards — rope bindings and repeated beatings every two hours — and after a failed suicide attempt signed a confession admitting crimes against the civilian population.

The third reason not to surrender — 53-year-old colonel Hambleton knew too much. Before the Vietnam War he was in charge on nine launch systems of intercontinental ballistic missiles, but even the nuclear war would have been a minor topic in the hypothetical conversation between Hambleton and Soviet military advisers.

Stunned from his fall, a very valuable prize for them was lying in a rice paddy — an expert on electronic warfare, detection, jamming, and destroying radars of the air defense systems S-75 Dvina.

US Air aviation started bombing North Vietnam in March 1965, and on July 24 near Hanoi two divisions of S-75 under the command of majors Boris Mozhayev and Fedor Ilyinykh shot four missiles at a group of Phantom fighters, and downed one of them.

The following eight years of the war were marked by the violent confrontation of the US Air Force and USSR anti-aircraft defense. Devices, which gave an alert when entering the radar zone, were developed and installed on American planes. Air-to-surface missiles, homing to the signal of anti-aircraft radar, were developed, as well as powerful jamming systems.

In response, Soviet experts were improving air defense systems right on-station in the jungle, developed new application tactics, and trained the Vietnamese to use it.

On April 2, 1972 a couple of Douglas B-66 destroyers from the electronic warfare unit were accompanying three strategic bombers in a raid on North Vietnamese communications. Their equipment diverted the first salvo of S-75. However, the next salvo was fired directly at the dots in the sky, and the radar was turned on only after the launch, so that it would not be jammed.

Soviet missiles lost the target if the acceleration was more than 2g. So when the pilot saw two 10-meter ‘telegraph poles’, as the Americans called them, in the sky, he tried to make a sharp turn. This time he failed — fragments of the first missile damaged the plane, and fragments of the second missile destroyed it.

It was a catastrophic, almost criminal mistake — because of the shortage of pilots, the squadron's planner, Iceal Hambleton, joined a combat mission as a navigator. Now he and all his knowledge about electronic warfare, nuclear weapons and aviation tactics were hiding in the woods amidst the unfolding offensive of the People’s Army of Vietnam. In the 8 km radius around him there were three infantry divisions, 150 tanks, fifty artillery pieces, and the biggest air defense force in the history of this war, which included air defense systems and 75 anti-aircraft guns.

Against him were the broken finger and bone in his left hand, four compressed vertebrae, and shrapnel wounds. On his side was training on jungle survival, two emergency radio stations, a first aid kit, a knife, a revolver, a compass, a map, and an empty water bottle.

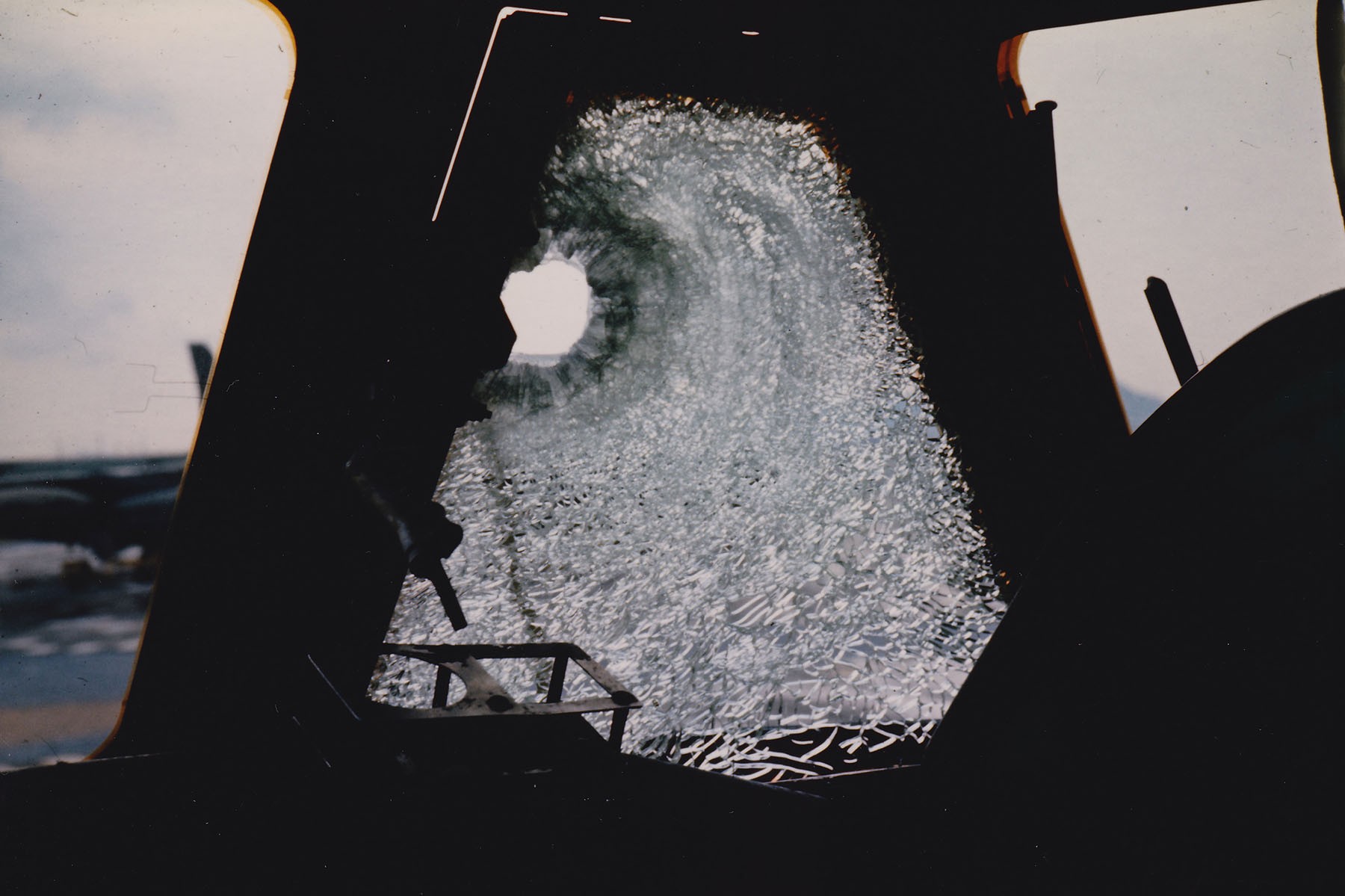

When pilots were downed, their evacuation needed to be done immediately: in only four hours after they parachuted the changes to save them were down to 20%. When Hambleton sent his coordinates over the radio, two Huey helicopters were dispatched covered by two attack aircrafts. They had no chance. The pilots will later say that the fire over this patch of land was as thick, as above Hanoi, the capital of Communist Vietnam. One of the helicopters was downed, killing three crew members and making the fourth one a POW.

When it was clear that a quick saving operation was not happening, Hambleton dug himself a hole in the ground. This hole is where he’d spend the following six days.

All this time the enemy listened and understood American radio communications — for several hundred thousand dollars US Navy officer John Anthony Walker sold the encryption codes to USSR embassy in Washington. The North Vietnamese knew about Hambleton’s high status, so they made a trap out of his position and surrounded it with air defense systems. On April the 6th alone, S-75 systems that were stationed there launched more than 80 missiles. 23, 37, 57, 85, 100mm guns, infantry grenade launchers and brand new Strela-2 MANPADS were also shooting at the Americans.

From his hole Hambleton couldn’t see how Jay Crowe and Bill Harris’ rescue helicopters were riddled with bullets — both barely made it to the nearest airfield. He didn’t see how eight Douglas A-1 attack aircrafts that tried to create a way for the rescue team had serious damage. He didn’t see how a spotter place OV-10 was downed and the pilot was captured. The second pilot, Clark, parachuted on the other bank of the river and was now also waiting to be evacuated.

There was something he saw, though — and he would later call it one of the most difficult episodes in the whole story — the Vietnamese let Peter Chapman’s Jolly Green Giant approach him. Hambleton had already launched a signal flare to identify his position, when they started firing at the helicopter from everywhere, and it exploded with six people on board. The next day another spotter aircraft was taken down with a missile. The pilots parachuted successfully, but were captured by the Vietnamese and went MIA.

It was the seventh day of unsuccessful rescue operation when he heard on the radio a voice that told him to get ready to play golf. The first hole was hole number one at the Tucson National.

It took a navigator and a devoted golfer half an hour to crack the code. The HQ knew the Vietnamese were listening to the communication, so they informed the pilot about the distance and direction of his movement with the help of a golf course he knew very well. The first hole was 400m to the south-east. Hambleton started crawling.

The fifth hole was at Shaw Air Force Base — 360 meters straight to the east. Every time it brought Hambleton to a good hiding place: a wood, a gully or high grass. With the help of 18 imaginary holes, radio communication and observers in the air, the HQ lead Hambleton away from the mine fields, villages and several enemy’s battalions. A pilot, who lost a quarter of his weight, was suffering from dysentery and hallucinations, was now hiding in the bushes on the bank of Meiu Giang River.

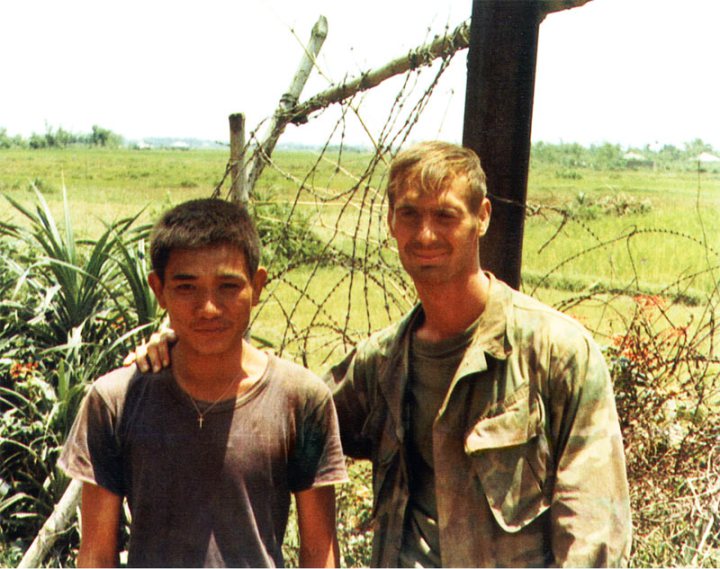

After the war, Hambleton liked to talk about the role of the individual in history. The key individual in his history was Thomas Rolland Norris. He was one of the few Navy Seals left behind after most of the American contingent was withdrawn from South Vietnam, and served as an advisor to local units.

After he evacuated Clark, he spent three days to get to Hambleton, avoiding the enemy’s patrols, and continued his efforts even after his American partner was severely wounded and evacuated, and all the South Vietnamese commandos except Nguyen Van Kiet returned to the base because the risk was too high.

Norris found and mended a broken sampan canoe on the river bank that someone left behind. Together with Van Kiet, dressed as a fisherman, they managed to reach Hambleton at night, when he almost lost the ability to move.

When the pilot saw two people dressed as locals approach him in a boat with Kalashnikovs in their arms, his whole life flashed before his eyes, but then he heard a code word:

— Red!

— White! Roger that.

— Let’s get your ass out of here!

For the first time in 11 days after he parachuted from the plane, Hambleton was finally safe.

In accordance with the Paris Peace Accords, by March 29, 1973, the US withdrew all their troops from Vietnam. The missiles of the Dvina S-75 systems had taken down about 200 aircraft according to US data, and about 1200 according to the USSR.

Iceal Hambleton started playing golf even more often after his retirement and lived until he was 86.

Thomas Norris was awarded the Medal of Honor for evacuating Hambleton, which is the highest military award in the US. There were only three Navy Seals who received it during the Vietnam War. In October 1972, he was severely wounded on a mission, lost one eye and part of his skull, but after nine years of treatment and rehabilitation passed his exams to enter the FBI. He served as an assault team leader on the FBI Hostage Rescue Team and is now retired.

Nguyen Van Kiet received the Navy Cross for his assistance during the Hambleton rescue, which is the highest award the US Navy can give to a foreigner. After South Vietnam fell, he was evacuated to the US and now lives in Washington.

John Anthony Walker, who among other secret information, sold US encryption codes to the USSR and was turned out to the FBI by his wife. He was sentenced to three life sentences plus 40 years more years imprisonment for treason and died in 2004.

New and best