Operation Condor: How Latin America Is Dealing with the Consequences of Political Repressions

Portuguese photographer. Born in Lisbon. Studied photojournalism and documentary photography at the International Center of Photography. Published his works in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Time Magazine, Newsweek, Stern, GEO, El País Semanal, La Vanguardia Magazine, D Magazine, IO Donna, Days Japan, and many other media outlets.

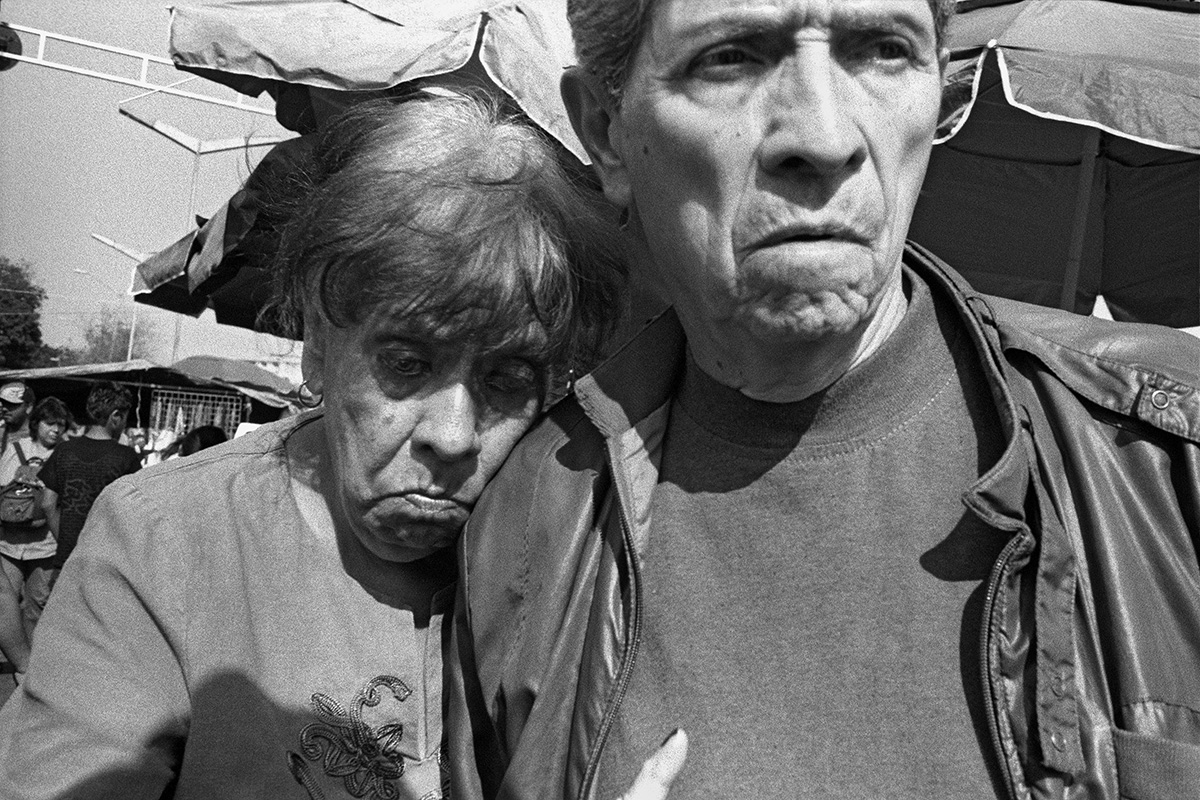

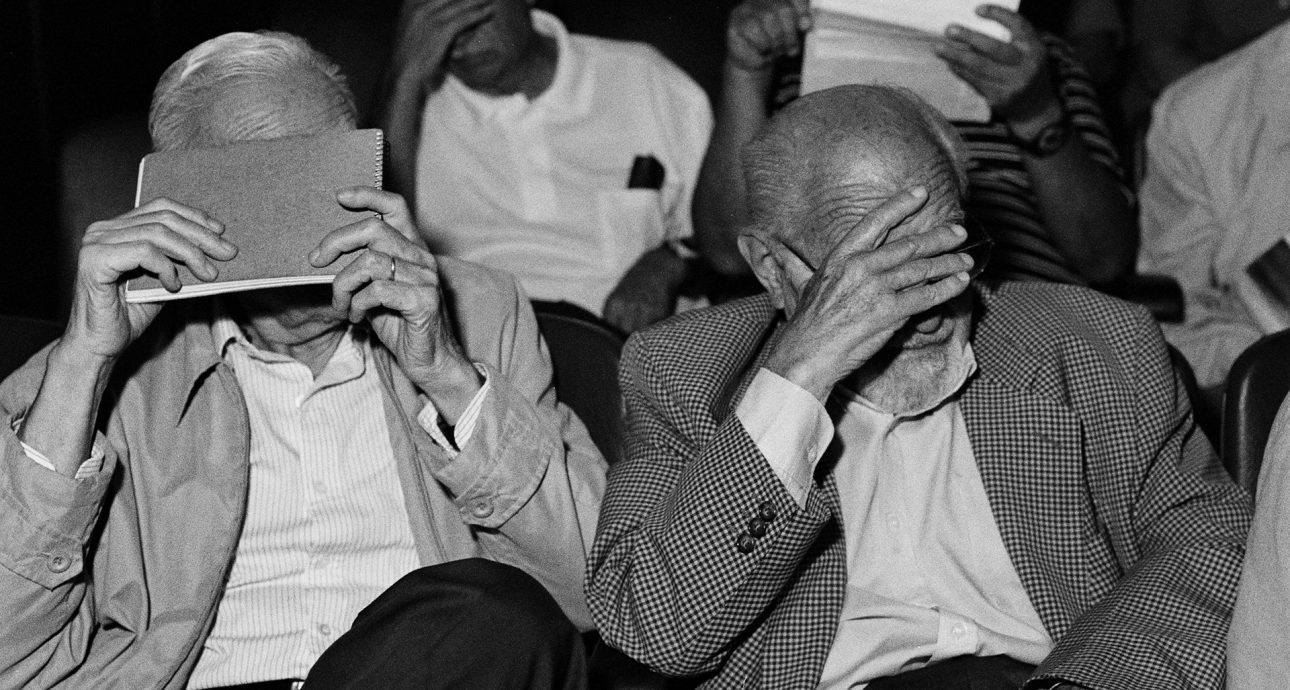

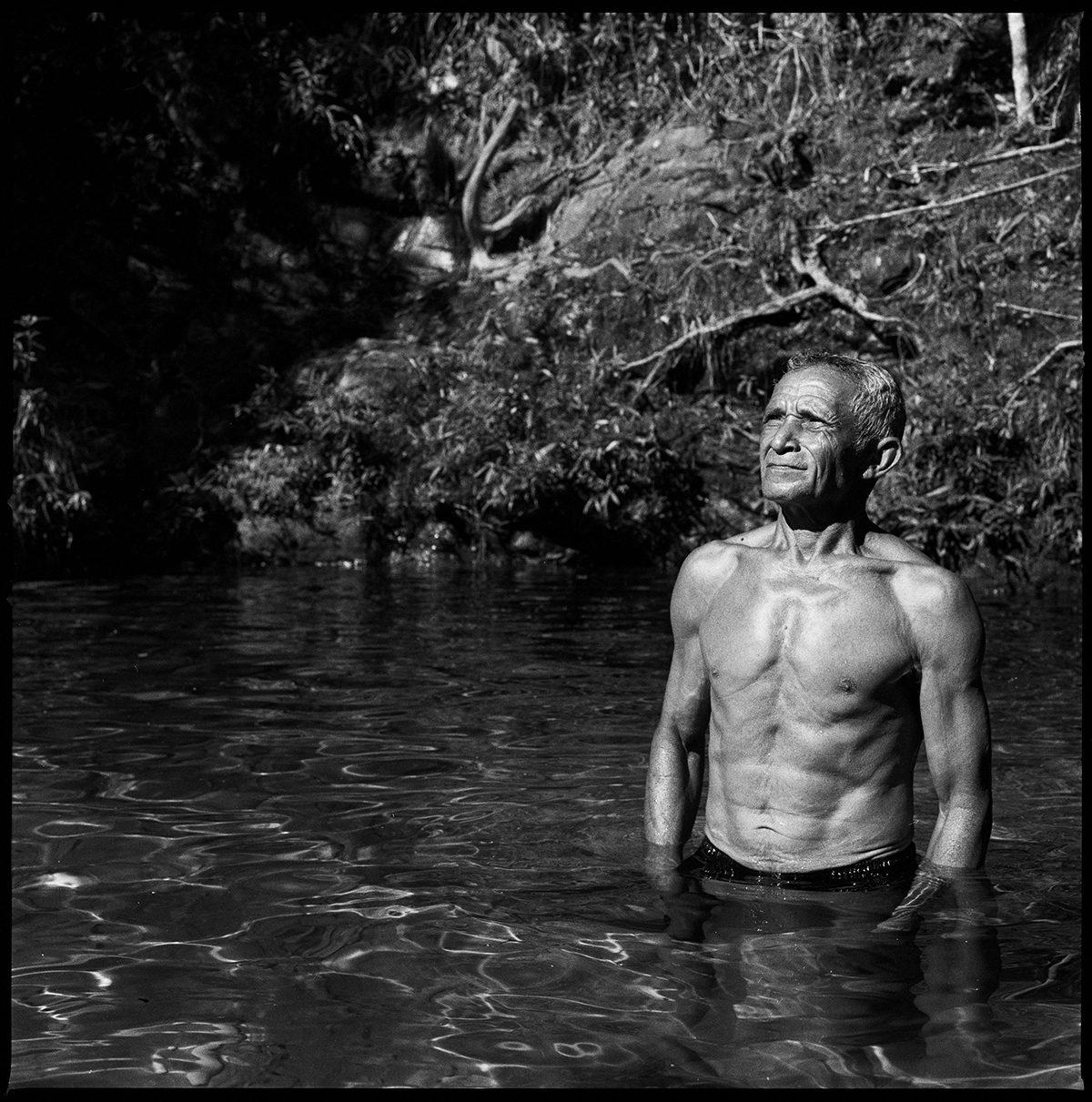

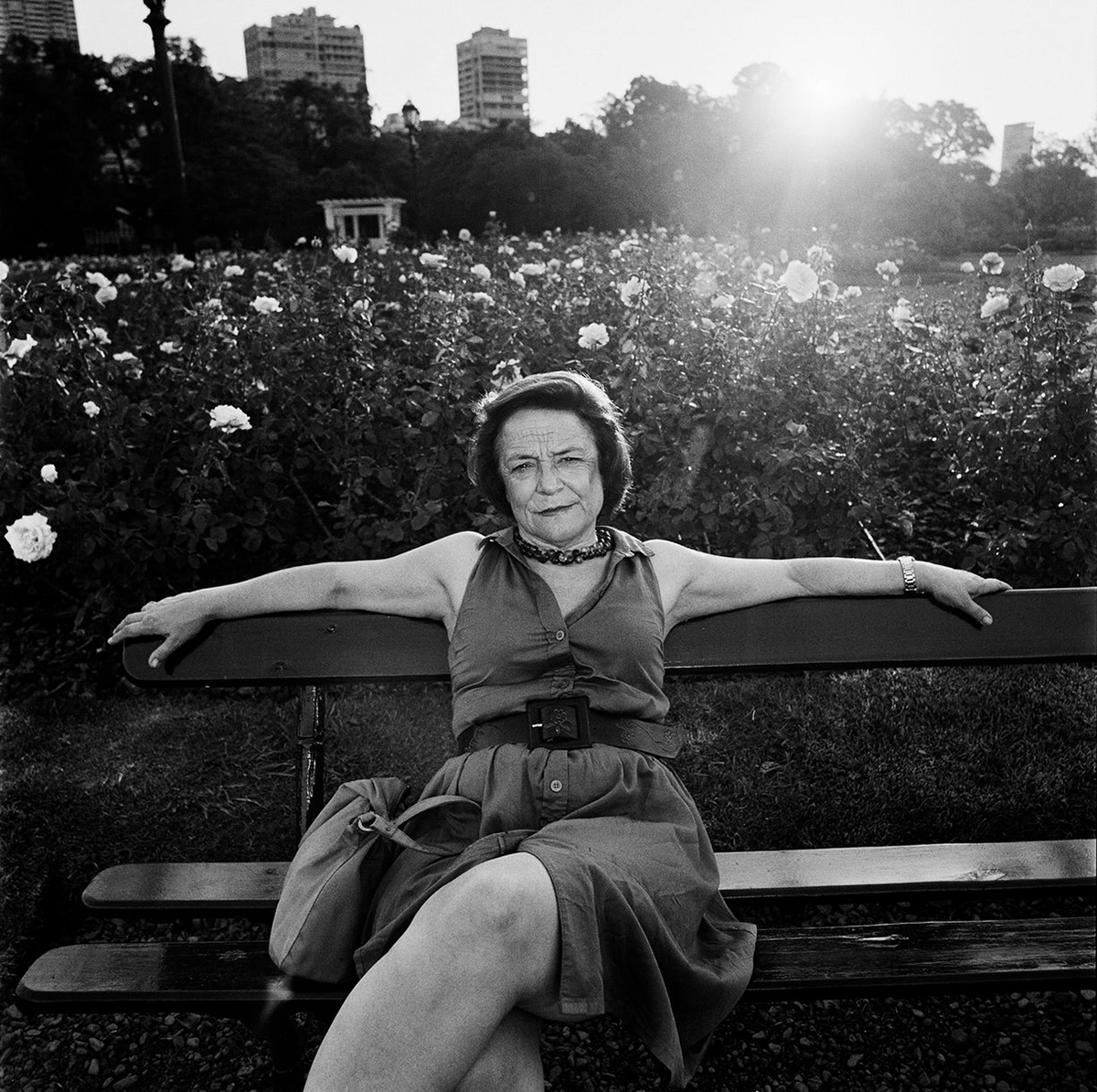

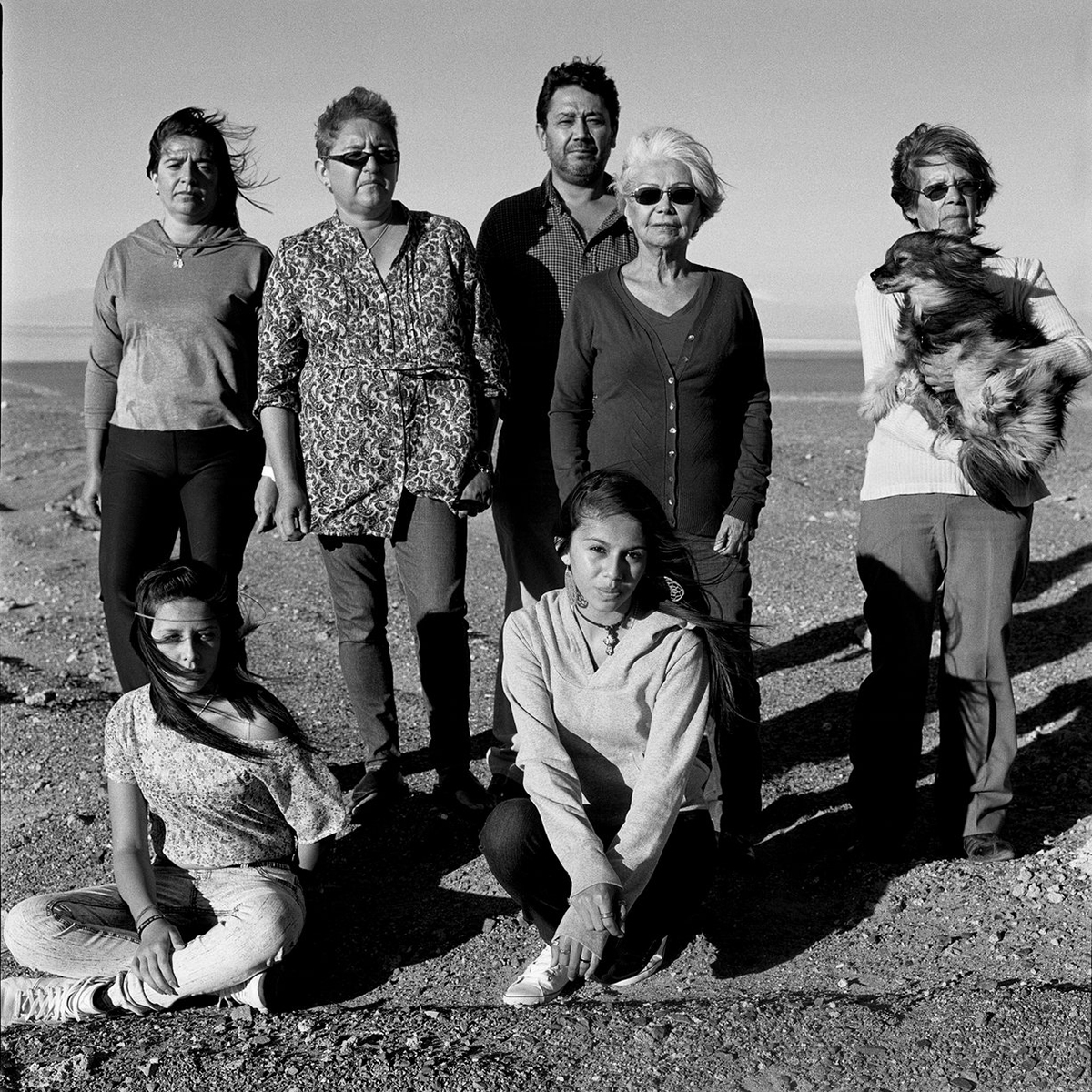

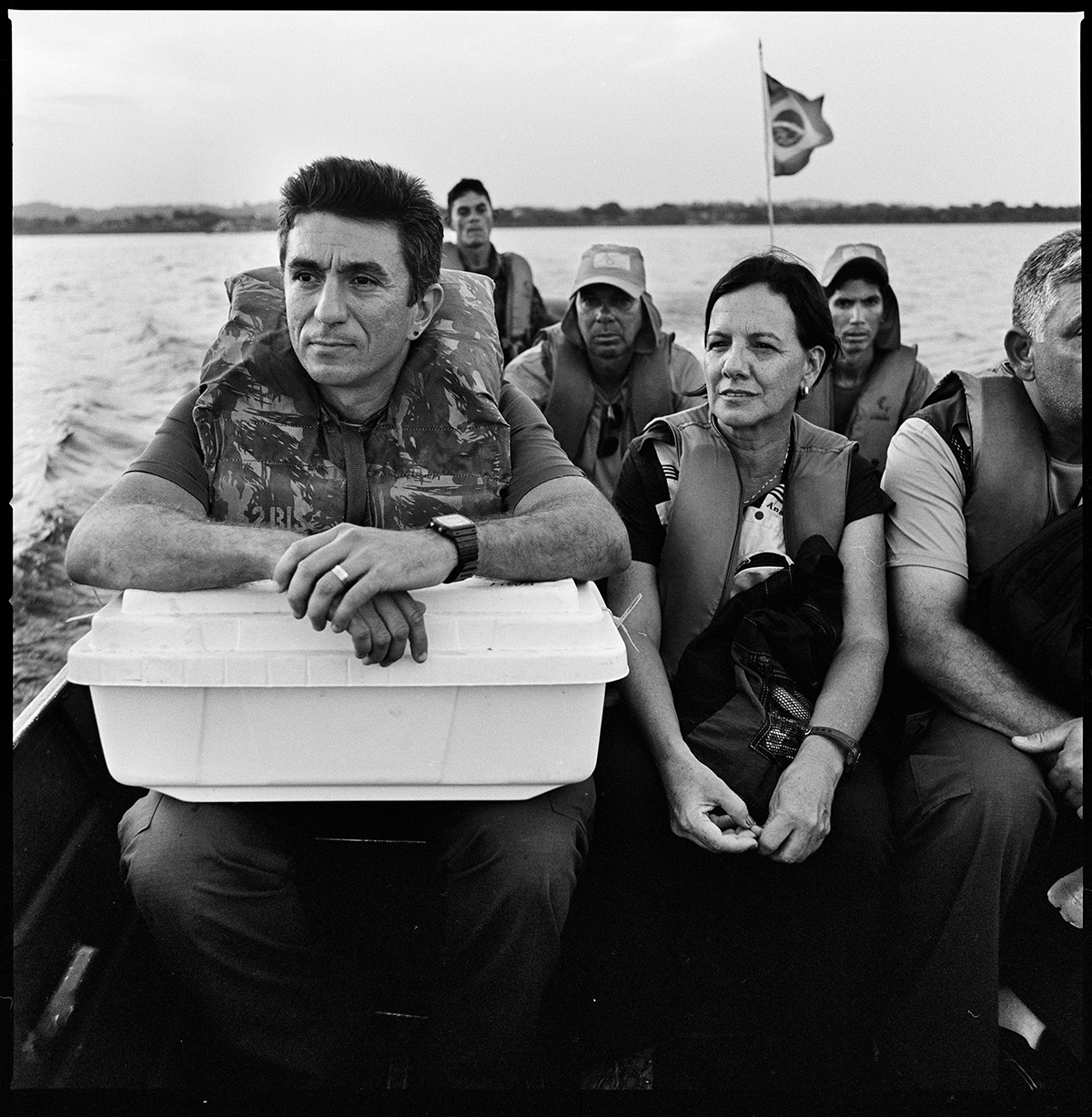

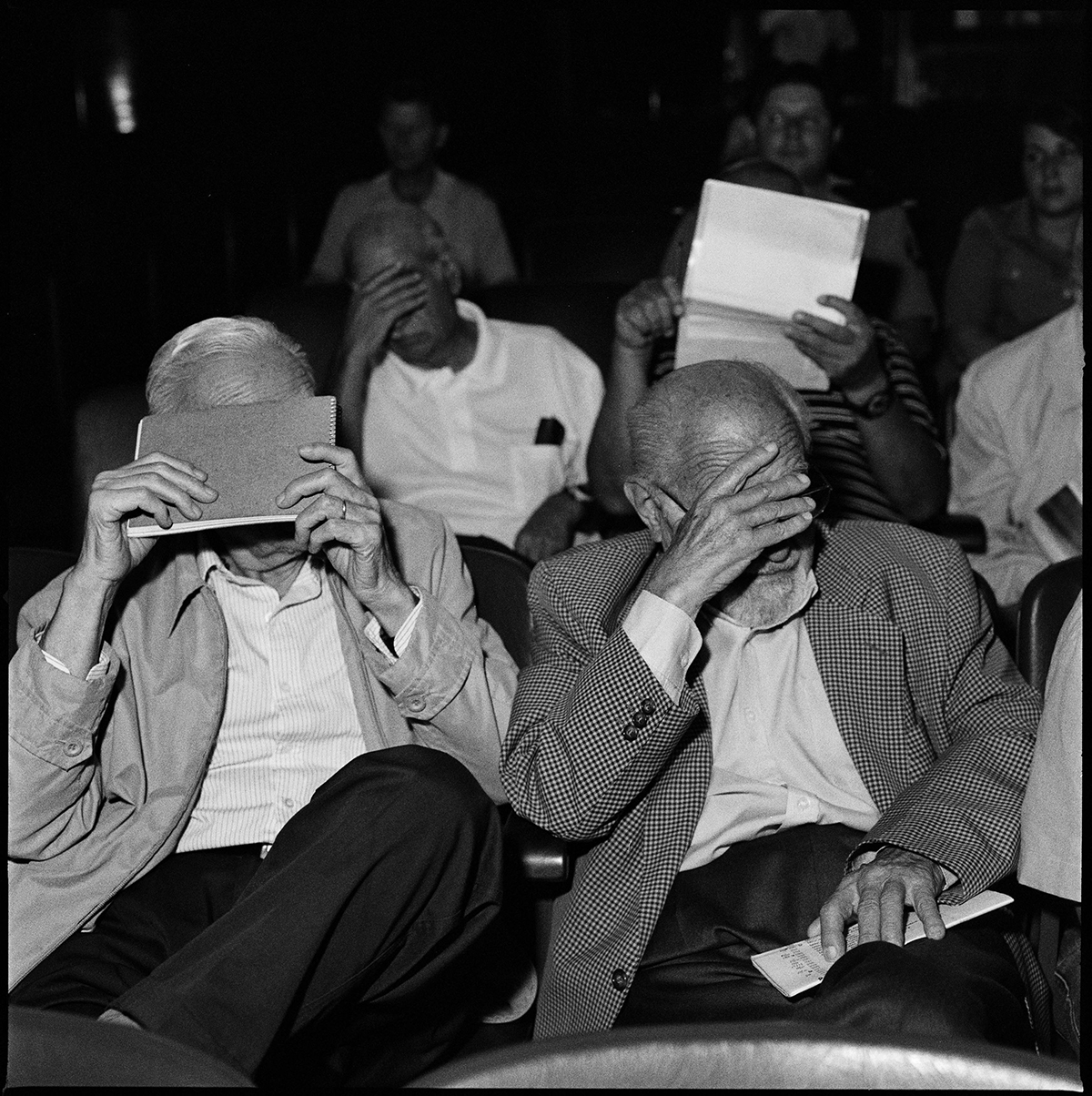

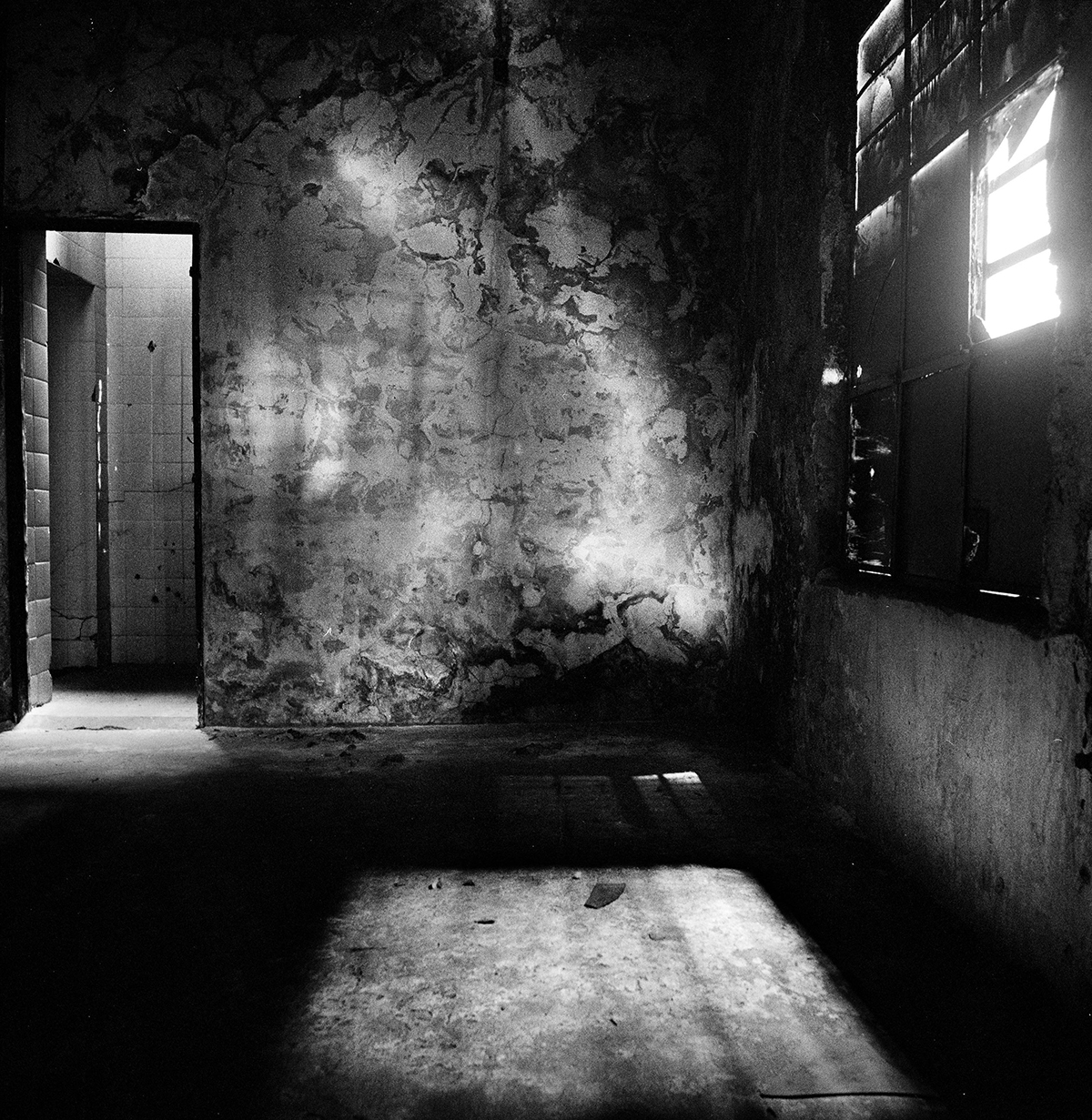

The exhibition of the works of Portuguese photographer João Pina will run as part of Les Rencontres d’Arles festival until September 25. It is a documentary investigation of the secret project of Latin American secret services called Condor. The operation started in 1975, in the height of the Cold War, when Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay joined efforts in prosecuting their political opponents. Over 60,000 people suffered at the hands of the secret services then: they were tortured in basements, thrown out of planes, and shot. It took Pina almost ten years to find and photograph the victims and their torturers, find artifacts related to those repressions, collect archives, and ask the question, what does a society need to do to overcome traumas like this one?

— How did you come to the idea of the project?

— My work started in my family history — that’s why I started with my first book about former Portuguese political prisoners. But Condor itself started with my passion that I have had for Latin America for years and the desire to continue to cover this type of subjects after I was done with my first book. That’s when I read about Operation Condor, by reading random things I found out that this has happened.

— So your field in general is historical memory?

— My field goes a long way, I cover from sports to historical memory. My personal projects go a little bit through historical memory for very personal reasons, and also forgotten stories. As a photojournalist, I also cover conflicts, I cover regular politics, social issues, a little bit of everything.

— Did you feel that people were in denial about what had happened when working on your project?

— Not really. When they see an honest approach to it, they usually open up. There was one person that denied me an interview, but for other reasons, it was more of dealing with her own memories. But most of the people are open about it, if you approach them from the right perspective. Not only in historical memories — my next book is going to be about violence in Rio. And I have approached both the police and drug traffickers, and if you have an honest and serious approach, I honestly believe that you can get them. The initial contact isn’t hard, although only one decided not to speak, and a number of others denied me an interview, which is totally in their right.

— Did you notice the tendency to justify the violence?

— Absolutely. They say they were fighting against leftist guerillas, but the vast majority of victims had absolutely nothing to do with any kind of armed opposition. The military are convinced that they were fighting a fair war.

— Do you see room for a project like this in Russia, with its history of Gulag that still hasn’t really been worked through?

— You can talk about Gulag, you can talk about Chechnya, you can talk about Afghanistan — there is a number of traumas in Russian society. But in Portugal there is the same thing: nobody talks about the dictatorship and nobody talks about colonial wars. The wounds are too painful to touch. The problem is, if you don’t clean a wound, it will never heal.

— What impact can the art project have on the society?

— If it can raise questions, I think the goal is achieved. If someone can come to an exhibition and go home with more questions than they had when they walked in, it is totally valid. And that is what I aim for, not for the art to create change, just to ask questions.

New and best