Then We Take Berlin: Wounded Victors in Valery Faminsky’s Photographs

The refusal of the Americans to capture Berlin is considered one of the strangest decisions in military history.

On April 1, 1945, British Prime Minister Churchill wrote to US President Roosevelt: “If they [the Soviet troops] also take Berlin, will not their impression that they have been the overwhelming contributor to our common victory be unduly imprinted in their minds, and may not this lead into a mood which will raise grave and formidable difficulties in the future? I further consider that from a political standpoint we should march as far into Germany as possible, and that should Berlin be within our grasp, we should certainly take it.”

On that same day, April 1, 1945 the intelligence information that the Western allies are planning to advance on Berlin and capture it before the Red Army does was discussed during the meeting of the State Defense Committee in Kremlin.

“So, who will take Berlin, us or the Anglo-Americans?” Stalin asked marshalls Ivan Konev and Georgy Zhukov. The two commanders of the 1st Belarusian and 1st Ukrainian fronts correctly took this question as an order.

On April 12, the Americans reached the Elbe River — they had 60 kilometers left till Berlin. The Germans fought fiercely against the Red Army, but their resistance to the Western allies was rather a formality. According to General Bradley, the city was at his feet.

Dwight Eisenhower, who commanded the Anglo-American troops in Europe, said that he wanted to save the lives of his soldiers. Perhaps, the US also did not want to lose the USSR as an ally in their war with Japan. They promised not to cross the Elbe — and they didn’t.

Joseph Stalin did not trust his Western allies and wanted to capture Berlin quickly, which meant by assault.

“Encircling [the city] would have been enough, they would have surrendered after a week or two. During the assault operation, right before the Victory, we left no fewer than 100,000 soldiers in Berlin’s streets. And they were as good as gold — they have been through so much by that time, and every one of them was thinking that they will see their wives and children very soon…” Hero of the Soviet Union, Army General Alexander Gorbatov wrote after the war.

The larger part of Wehrmacht was outside Berlin, the supporters of Stalin’s plan remember. According to them, without Hitler’s suicide and the capitulation of the government, five million German soldiers would have resisted for much longer.

The Soviet army had three times as many soldiers and officers as the defenders of Berlin and five times as many artillery weapons and tanks. The Wehrmacht was critically lacking fuel and munition. There were almost no Luftwaffe planes in the air.

Marshall Zhukov decided to use the quantity advantage and advance in a broad front. The Battle of the Seelow Heights is remembered every time they speak about how merciless he was to his own soldiers.

During the two months of the lull, the Wehrmacht built three defense lines along the Oder River. The natural barriers were enforced with a system of fences, ditches and minefields, a dense network of trenches, bunkers, and hidden artillery positions. By destroying the dam, the engineers turned a plain in front of Seelow Heights into an endless swamp.

Zhukov ordered a frontal assault by the 1st Belarusian Army.

The Germans had taken a prisoner shortly before the offensive, and found out the planned date — April 16. The preliminary artillery shelling by the Red Army was fruitless — the enemy had retreated, took shelter, and then met the infantry with all their guns firing.

It took three days to advance through the Seelow Heights, after introducing two tank armies into the battle, and by sacrificing the lives of 30,000 Soviet soldiers.

The Soviet losses on the Seelow Heights were excessive, but not in vain. The Red Army managed to destroy the 9th German Army there and not let it retreat to Berlin. That’s why the capital of the Reich was defended by militia, the elderly and teenagers, policemen, the remnants of units that were defeated in the battlefields, and Hitler’s personal guard. The capital’s garrison was no more than 60,000 people — against 460,000 Soviet soldiers with 1500 tanks.

British historians called Berlin ‘a fortress with paper walls.’

Even with such an advantage in numbers, the Red Army suffered tremendous losses. When the troops mixed in battle, aviation became ineffective. The thick walls of the buildings did not yield to shells; and from the buildings, defenders of Berlin were firing Faustpatrone at tanks.

The only thing worse than the lack of experience with urban warfare was the wish to capture the buildings that were symbols of Berlin and the Reich as soon as possible. Two or three thousand of soldiers died only to have the red flag raised on the roof of the Reichstag, the German parliament.

The resistance was suppressed ruthlessly. According to Marshall Yakovlev, during the offensive the Soviet troops used about 10 million artillery shells, 392 million cartridges, and almost three million hand grenades. The city center was shelled with fortress guns, with 0.5-ton munitions.

On April 30, 1945 Hitler finally realized how hopeless the situation was, and ended his life. On May 2, Berlin garrison surrendered.

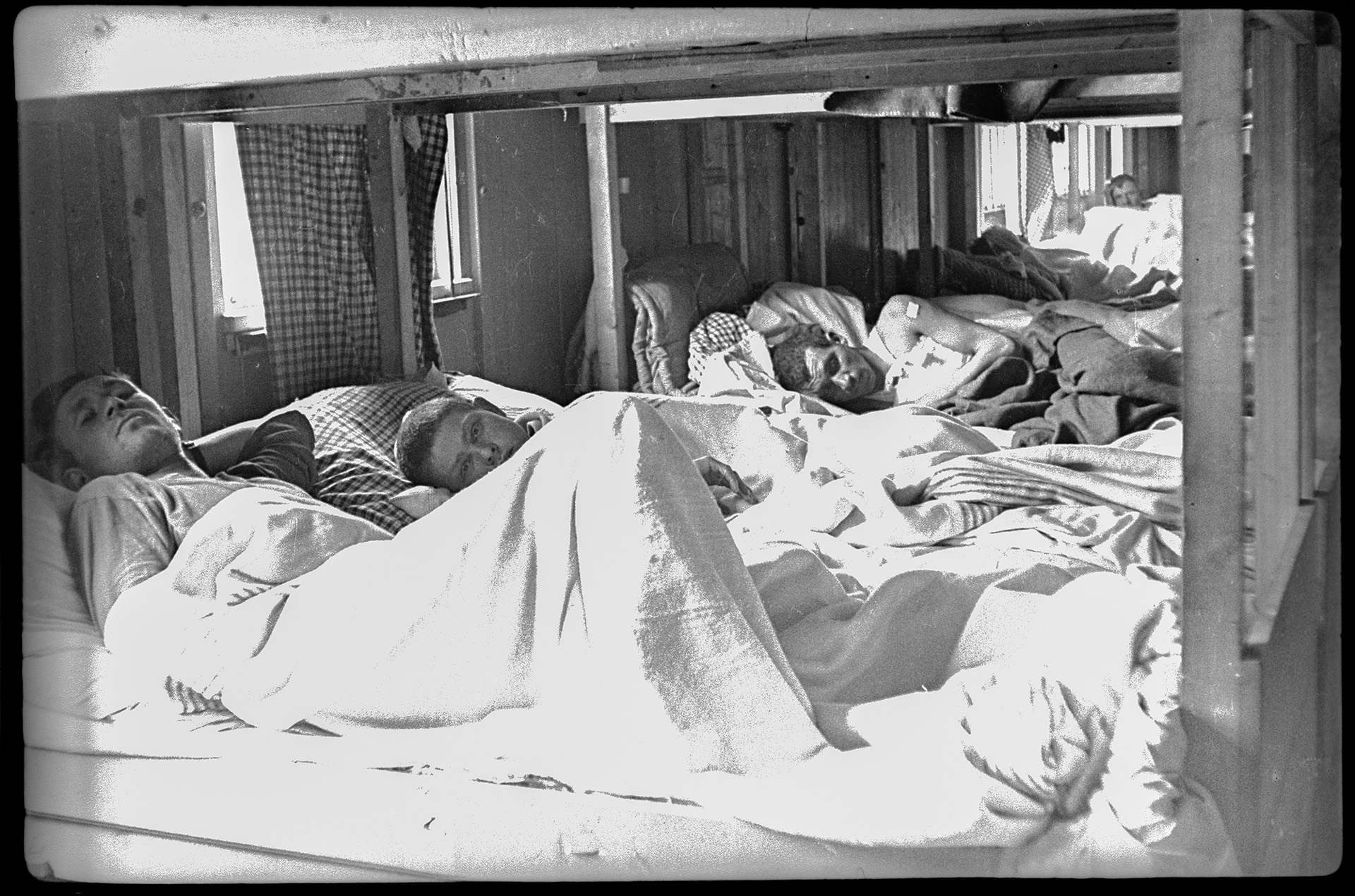

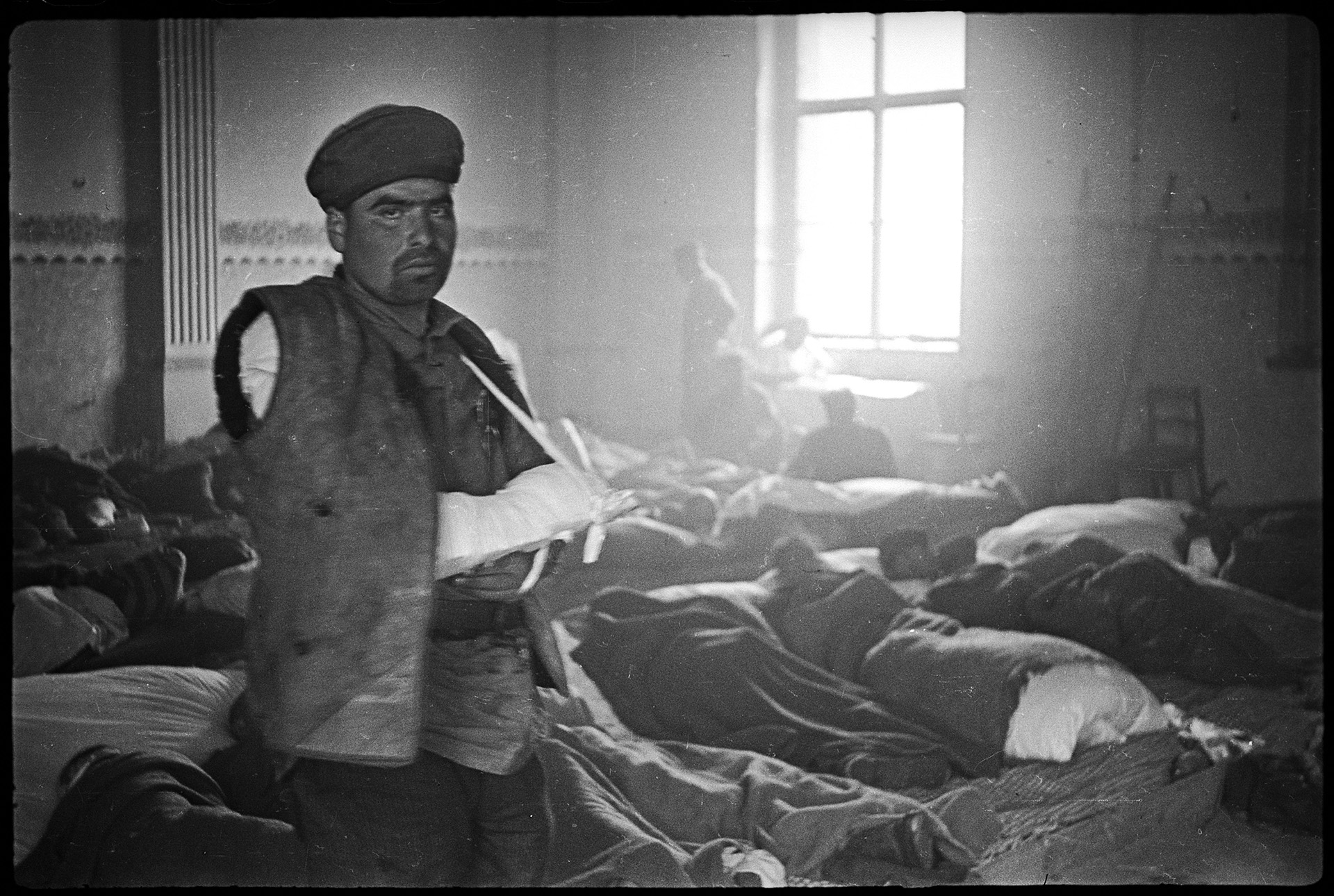

The joy of victory was spoilt by the record losses of the Red Army — on average, 15,700 killed and wounded soldiers for each day of the offensive. By comparison, this number was 10,900 under Moscow, 6,400 under Stalingrad, and 11,300 on the Kursk salient.

If Berlin was taken by the Western allies, over 80,000 Soviet soldiers would have survived.

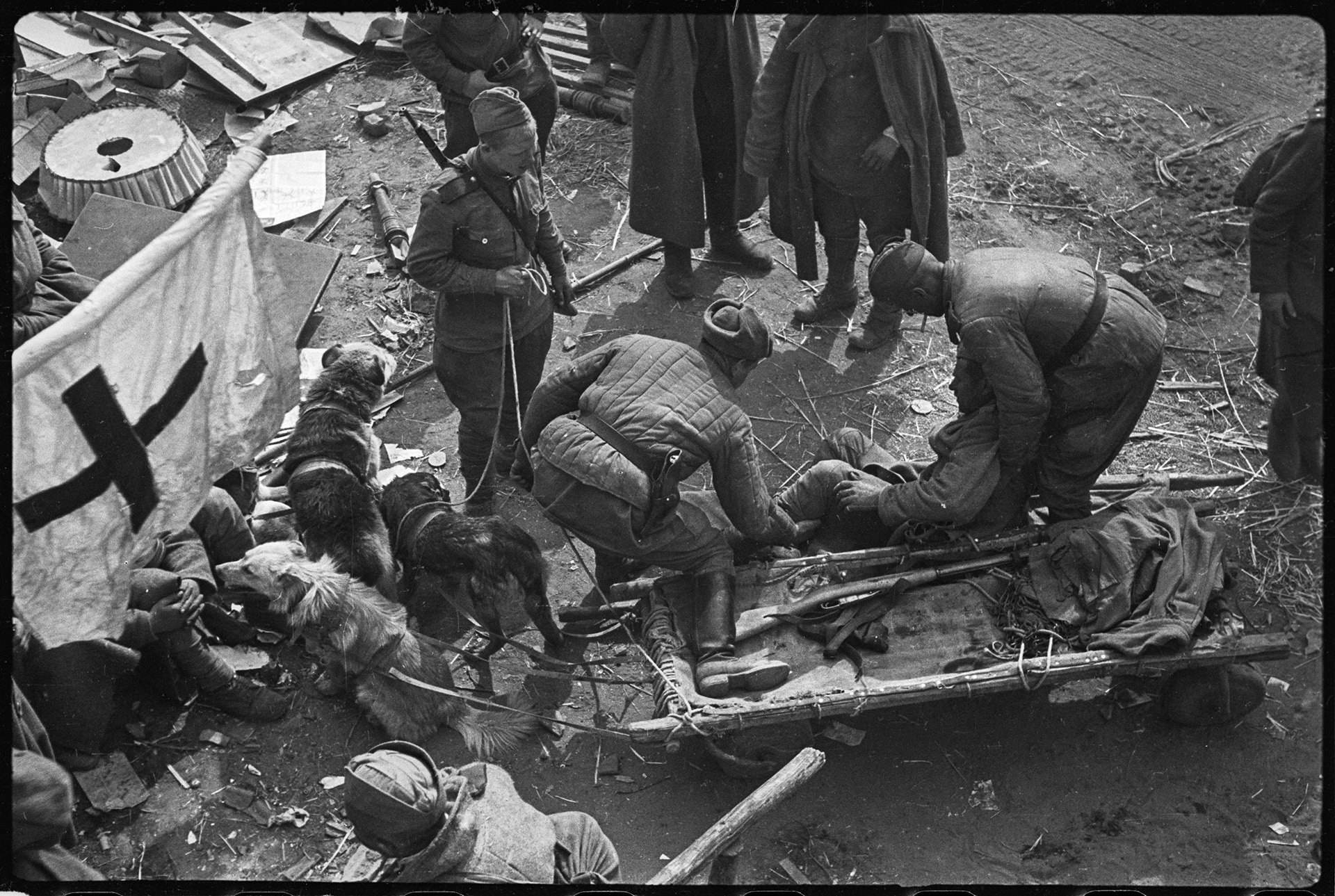

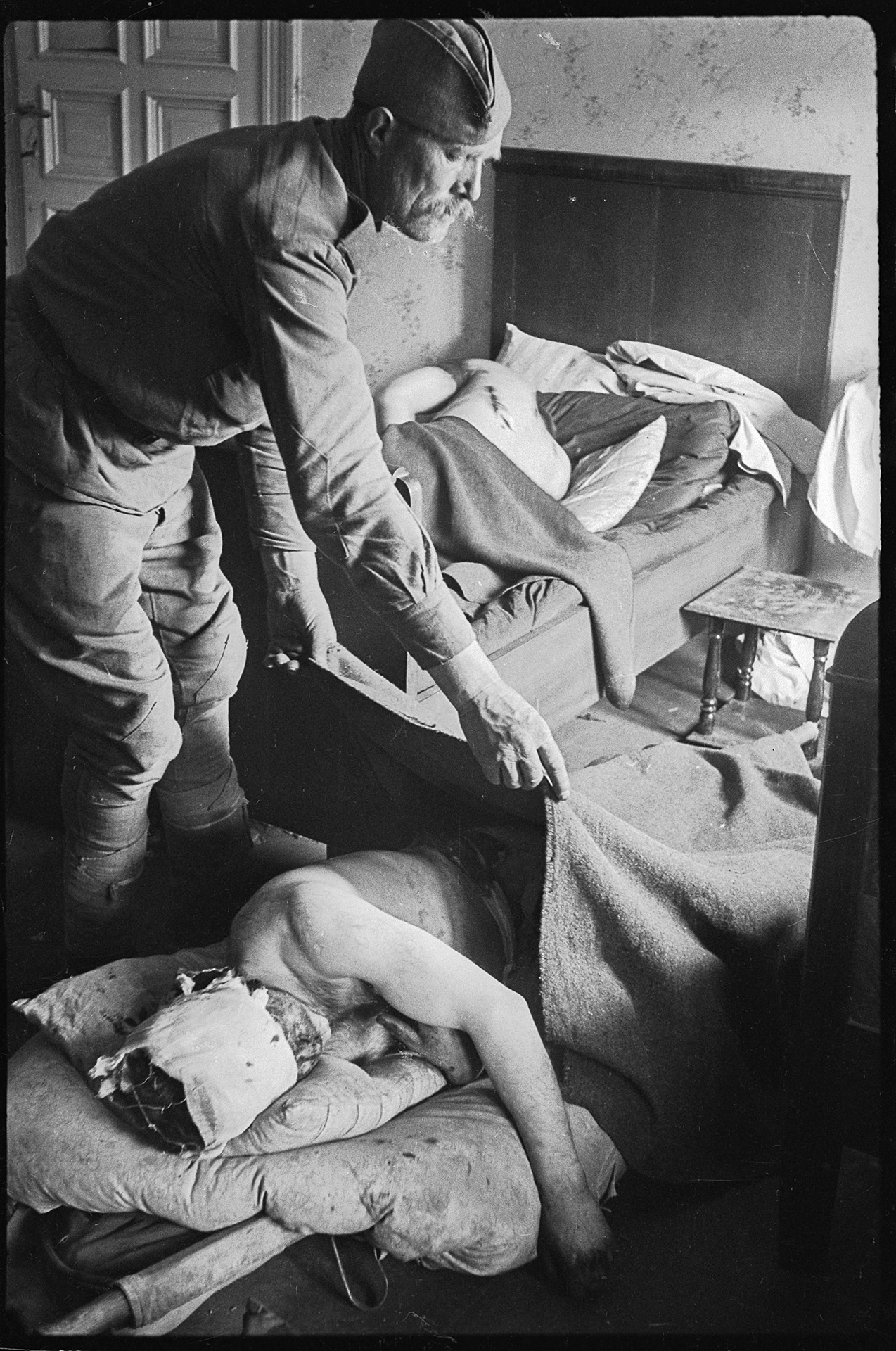

Photo: Valery Faminsky, Arthur Bondar’s private collection. Berlin, May 1945.