No longer ashamed: how Zinaida Serebriakova brought women to life

Painter Zinaida Serebriakova was born in Neskuchne, Kharkiv Region, but spent her adult life between St. Petersburg and Paris. You have definitely seen her works: a self-portrait in the mirror or as Pierrot, the painting of her daughter nude, and others. Also, she depicted her native Neskuchne in one of her works. When her family fell into poverty and her estate was plundered, the 36-year-old Zinaida found some work in the Kharkiv Archaeological Museum. Those were the last months she spent in Kharkiv, where she would never return.

In 1924, Zinaida Serebriakova arrived in Paris, albeit with only two of her four children. She would not see the other two until before her death. The last depiction of the four of them together is House of Cards, a painting that is considered prescient.

Most of Serebriakova’s works are exhibited in museums outside Ukraine. So, can she be considered a Ukrainian painter, for she was born and spent a period of her life here? Oleh Koval, an art critic and National Union of Artists of Ukraine member, told Bird in Flight if Serebryakova should be “Ukrainized”.

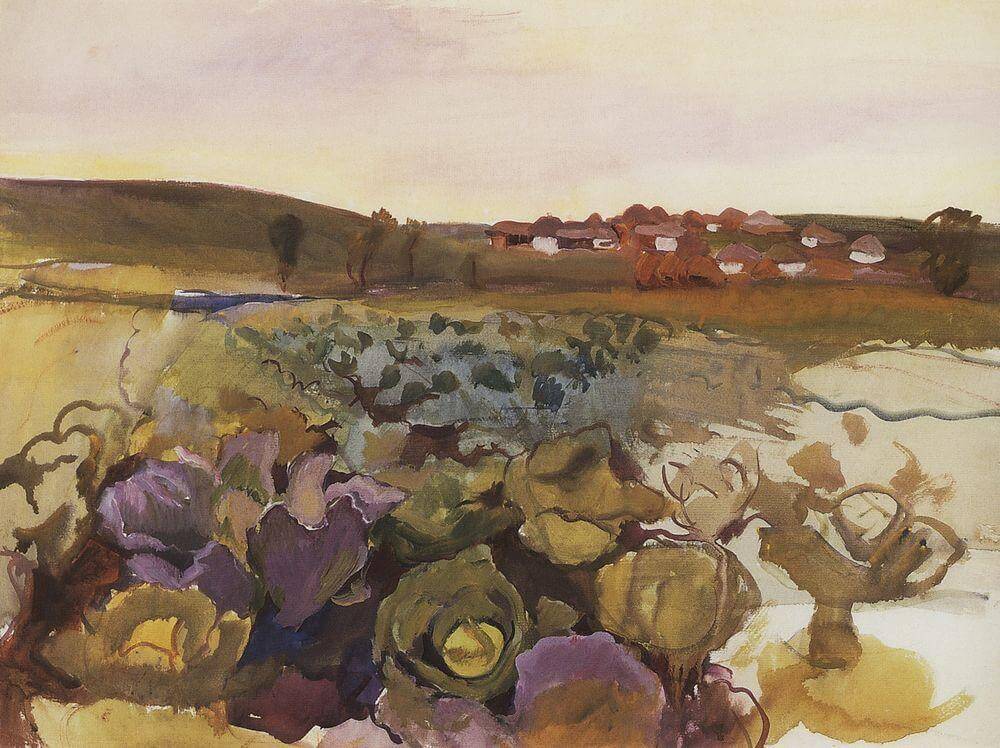

Cabbage. Village Neskuchne, 1909

Serebriakova spent her childhood near Kharkiv and worked in the local fine arts museum, so she might as well be considered a Ukrainian artist. On the other hand, she was born into the Benoit-Lanceray family, spent all her adult life first in St. Petersburg and then in Paris, was a member of the Russian Society of Young Artists and the World of Art society, and took cues from

Serebriakova’s works stand out because she returned to the motifs prevalent in the 18th century. An excellent example is looking glass making a return in her self-portraits, much in the vein of Spanish painter Diego Velázquez. Admittedly, Serebriakova had an eye for the things that mattered in art.

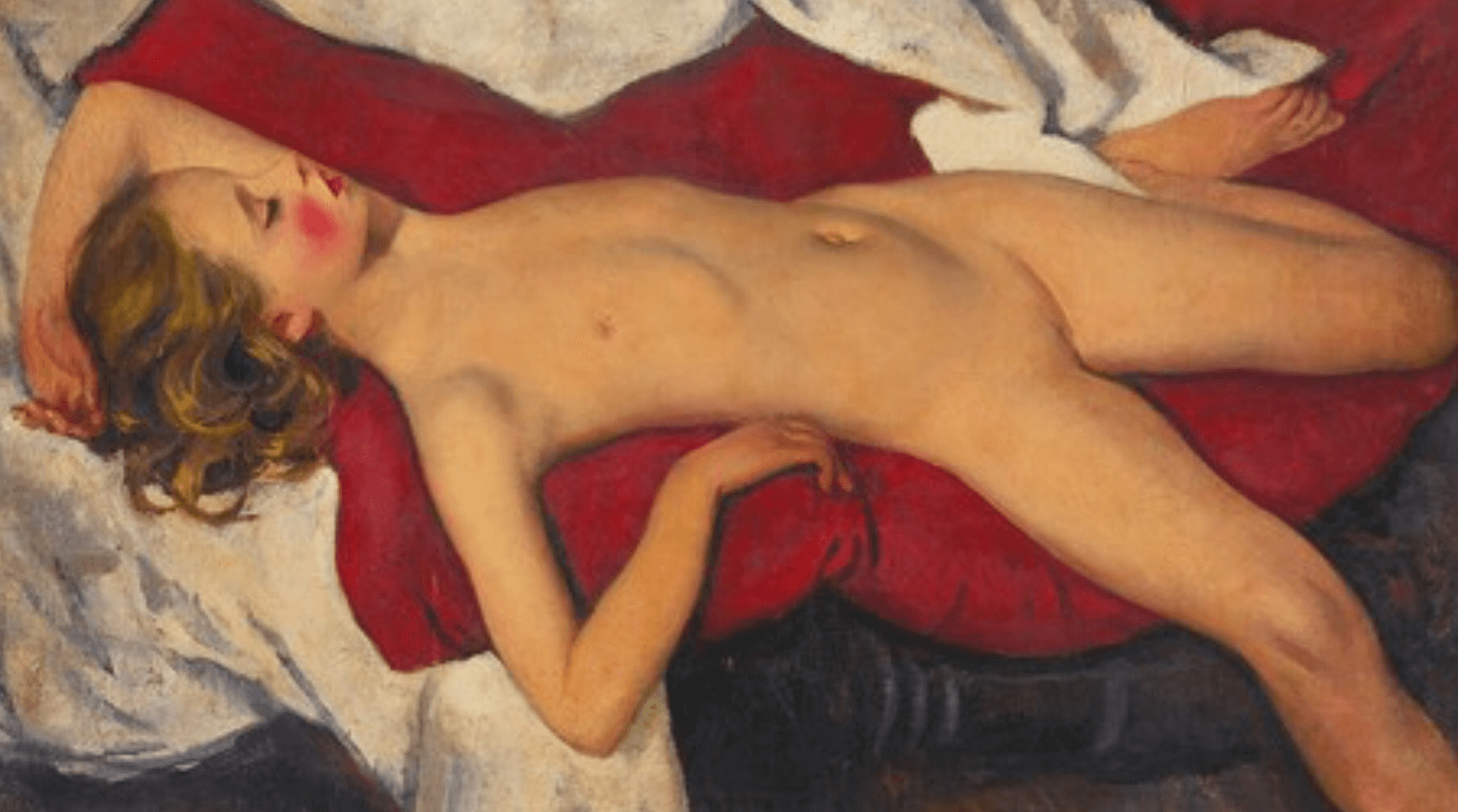

She brought the themes of love of family, home, and one’s surroundings to the art on the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 1910s, artists depicted women as enigmatic beings. Take Portrait of Ida Rubinstein by Russian painter Valentin Serov, for example. In it, she is cold, fragile, and detached. Meanwhile, Serebriakova’s self-portrait shows us a beauty in the mirror — alive, genuine, and with a rosy complexion. She is not hiding that she had just woken up and sits in front of us combing her hair, unashamed of wearing only her undergarment.

In the 1910s, artists depicted women as enigmatic beings. Meanwhile, Serebriakova’s self-portrait suddenly shows us a beauty unashamed of wearing only her undergarment.

circle of Russian artists that gathered around Aleksey Venetsianov. They mainly painted rural landscapes, interiors, and still life.

At the Dressing Table. Self-portrait, 1909, Tretyakov Gallery

Self-portrait, 1910

Serebriakova took cues from Neoclassicism — her works are reminiscent of Nicolas Poussin — and Venetsianov’s school of art with its focus on rural imagery. Her artwork was vivid: she could make anything look grandiose in her paintings. However, she stopped at the threshold of avant-garde, never crossing the line. That is to say that Serebriakova didn’t revolutionize pictorial arts and stuck to was artists did in her time.

Meanwhile, Ukraine has such artists as Oleksandr Murashko and the Krychevsky brothers, and these are giants. Compared to Serebriakova’s paintings, their works have the advantage of scale, level of technique, and interesting ways of tackling plastic problems. They move to the 20th century already, while Serebriakova remains at the turn of the century.

At Breakfast, 1914

Sleeping Girl, 1923

House of Cards, 1919, the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

I believe we must focus on restoring the reputation and glory of our artists. Granted, we shouldn’t give up on Serebriakova. Still, we need to understand that we are talking about a Russian artist who lived in Ukraine in her case. There were attempts to bring up her connection to Ukraine. For instance, some of her studies were returned to Kharkiv owing to the efforts of art critic Mykhailo Krasikov. Her paintings now cost a fortune — at least $50,000 for one. We could argue for returning her sketches, but would it change anything? Meanwhile, the works of Ukrainian painting genius Tatiana Yablonska or our contemporary Pavlo Makov crucially need to be preserved. I mean, the issue of Serebriakova is not an issue at all. Our goal now is to keep Ukrainian art safe.

Harvest, 1915, Odesa National Fine Arts Museum

Bath-house, 1913

Photos: Wikimedia Commons

New and best